The OHO Files: Interview with David Nez

ARTMargins Online publishes exclusive interviews with former members of the Ljubljana-based OHO Group, which formed in the late 1960’s and consisted of Milenko Matanovi?, David Nez, Marko Poga?nik, and Andraž Šalamun. It belonged to the wider Slovene OHO Movement and regularly collaborated with this wider circle of intellectuals and artists.

David Nez was born in 1949 in Massachusetts, USA. He graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Ljubljana, Slovenia. He joined OHO in 1968, participating in exhibitions, happenings, photo projects and films. At first, he created objects, followed by environments and installations. Notable among OHO’s “Summer Projects” are his installations of mirrors positioned in the landscape. Later, a number of processual works were produced, followed by several conceptual projects dealing with the relationship between time and space. His last exhibition in Yugoslavia was held in 1972 at the Salon Muzeja savremene umetnosti (Salon of the Museum of Contemporary Art) in Belgrade, where he presented the work which earned him his diploma. From 1971 to 1972 he was a part of the Šempas Family. He now lives and works in Portland, Oregon.

BŽ: Why did you come from the USA to Slovenia?

David Nez: After the major earthquake in Skopje, Macedonia in 1963 my father worked for the United Nations as a City Planner, helping to reconstruct the city. He took me with him to live for six months. During that period we also travelled to Slovenia and met relatives there. This was the first time I had travelled outside of the U.S. and I was fascinated with the cultures and exotic history of Yugoslavia. After graduating from high school I decided to return to Ljubljana to study art at the Akademija, mainly because I wanted to live in Europe and travel the world. This was also during the time of the Vietnam war which I opposed. I decided that if I was drafted into military service I would refuse to return to the USA and stay in Ljubljana.

BŽ: How did your family and friends in the States accept your decission to go and study in Slovenia? How did people accept you here?

DN: My family was supportive, since my father and I had briefly lived in Yugoslavia. I personally was not attached to a home in the USA. My family had moved several times before settling inWashington DC in the mid-1960’s. I had gone to three different schools in three years. I already felt “rootless” before moving to Slovenia so it was no shock to me to leave America. I was generally welcomed and well accepted in Ljubljana. In fact I enjoyed celebrity status as an American who acted in a slightly crazy manner. Because I was an outsider my odd behavior as a member of OHO was more readily tolerated, I believe. I was already outside the cultural conventions so it was easy to live on the edge.

BŽ: How did you come together as a group?

DN: I originally met Milenko Matanovic as the result of displaying some painted aluminum objects, which he saw. He was making similar objects—also hard edged paintings, and we found we shared artistic interests. A friendship quickly developed between us. We began collaborating on some “happenings” and I was soon introduced to Andraz Salamun and other OHO group members.

BŽ: Did you as a group feel connected to the things Marko Poga?nik was doing before or did you feel as a new, independent structure? Was there maybe a connection to your previous work, or to the previous work of Milenko and Andraž?

DN: If memory serves me right Marko was serving in the army around the time I started with OHO. I was familiar with his work and found it interesting but was more directly influenced by the work of Milenko and Andraž in the beginning as we collaborated a lot at that time on “actions” and “happenings” at Zvezda Park as well as making “objects.” If I remember correctly, Milenko, Andraž and Tomaž and I worked together while Marko was gone, culminating in the “Pradjedovi” exhibit in Zagreb. Marko joined us again during the exhibit at Moderna Galerija and in the following shows, and our group constellation changed again when he returned.

BŽ: Do you think that your American background influenced strongly your work in the OHO period, and also the group as a whole?

DN: Yes, definitely. I think I was welcomed as a cultural “outsider” and my different point of view was appreciated. As an American I was seen as exotic and free of the conventional cultural attitudes of Slovenians. Being American allowed me to act in ways that were offbeat and at odds with the status quo and get away with it. They also liked to practice their English on me, and they loved my pathetic attempts at speaking Slovenian!

BŽ: Does that mean that the members of OHO spoke English when they worked together?

DN: No, only when speaking with me, and I did make an effort to speak Slovenian, though I never spoke well. Maybe I spoke “Dada” Slovenian…

BŽ: Can you describe the interaction among the group members?

DN: From the beginning we were friends and collaborators. Milenko, Andraž, and I spent lots of time hanging out together, discussing ideas as well as playing and goofing around. Art making was the primary focus and purpose of our lives in those days. We had our obvious personality differences but these seemed to complement each other. Tomaz Šalamun was like our older brother, a mentor, a mature and successful artist we looked up to, who took us under his wing, appreciated our talents and helped us develop. Later when Marko returned from the army we would visit him and Marika at their house outside Kranj. Some of my favorite memories were the times we would go mushroom picking in the forest and Marika would fry them up into omelets. It was like a family. With Marko I always felt a sense of awe. There was something exotic about him, an intelligence and charisma that were inspiring.

BŽ: How did you work? If you knew you would have a show in some months or in a year, how did you prepare for it? Did you do works for the show, or did they exist before and were just shown?

DN: Our work was focused very much on specific projects or exhibitions. These gave us a structure and time-frame to work towards. We would share ideas with each other and work towards the goal of the exhibition. As I previously mentioned, collaboration was a big part of what we did, but usually with a sense of coming up with our own individual solutions to artistic projects. In this sense there was a good natured competition between us. We encouraged each other to do our best and push ourselves to the creative limits.

BŽ: How did you decide on a certain theme? Or on a type of research, or specific materials? How did you finance your projects? Did you sell any of your works?

DN: I think our themes grew organically out of the particular exhibition we were working on, the available space and materials, as well as the synergetic evolution of the ideas we were sharing with each other at the time. Each show was a new effort and direction based on our underlying interest in experimentation, and the boredom associated with repeating ourselves. We often financed the work out of our own pockets, though when we showed in galleries or museums they often paid for the materials and provided a per diem. We certainly didn’t get rich off it, and I personally never imagined anyone would want to buy my work.

BŽ: I asssume you were aware of what I would call the great power and symbolic potential in the events on which you were working. . Was that more intuitive, or did you talk about this, may be even have a theory about it?

DN: I think it was more intuitive. We were aware we were in the midst of a whirlwind of possibilities—the “zeitgeist” of the 1960’s—and of the fact that we were unique as a cultural force. It was like being on a roller-coaster. I didn’t think about it too much, I just enjoyed being along for the ride.

BŽ: Were people invited to attend, for example for your “wood installations with mirrors, etc.”? Who was invited, and how?

DN: No, we just set up the work and photographed it for documentation. Whoever happened to be there witnessed it.

BŽ: So the aim of those projects was the photo-documentation? Do you or did you have any specific theory on exactly what is art in such projects?

DN: Yes and no. The projects were enjoyable to do, perhaps more so because of their ephemeral nature. The photos were necessary as evidence of their existence and to communicate them to the public. I personally believed that anything “framed” in the context of the art experience was art. For me art was the state of mind, the heightened awareness, like meditation, that occurred during the process of the art event. This became even more apparent during the photo projects since the goal was not to produce “objects” but to document experiences.

BŽ: Who worked with you or helped you with certain projects?

DN: Some projects I did on my own.With others I got some help with installation from whoever was around. We helped each other, but ideas mostly originated with the artist.

BŽ: How long did your actions last, like the actions with mirrors or in Zvezda Park?

DN: No more than a few hours, sometimes just minutes or even seconds with the photo projects! The Zvezda Park actions involved public interaction so they lasted as long as the public was interested or we ran out of materials; a couple of hours usually. I set up the mirrors for a couple of afternoons, photographing the arrangements I liked the best.

BŽ: I have chosen a number of your works I would like you to comment on. (All these works are reproduced in the OHO catalogue, edited by Igor Zabel and published by Moderna galerija in Ljubljana in 1994. In the following listings, the year of production is followed by the number of the page onwhich it appears in the catalogue.)

1. Action in the Zvezda Park; Spread roles of paper then crumpled into mounts, 1968, p. 38.

We performed alot of actions or “happenings” in the park, attempting to involve the public in spontaneous events. We had some theories about erasing the boundaries between life and art and taking art to the streets. It was “in the air” those days.

2. OHO – Katalog: Happening the Passion (or Biblical Stories), 1968, p. 39.

2. OHO – Katalog: Happening the Passion (or Biblical Stories), 1968, p. 39.

You should discuss this with Milenko, as it was his piece. I seem to remember it was about audience participation, as well as Milenko’s characteristic humor and love of the spectacle.

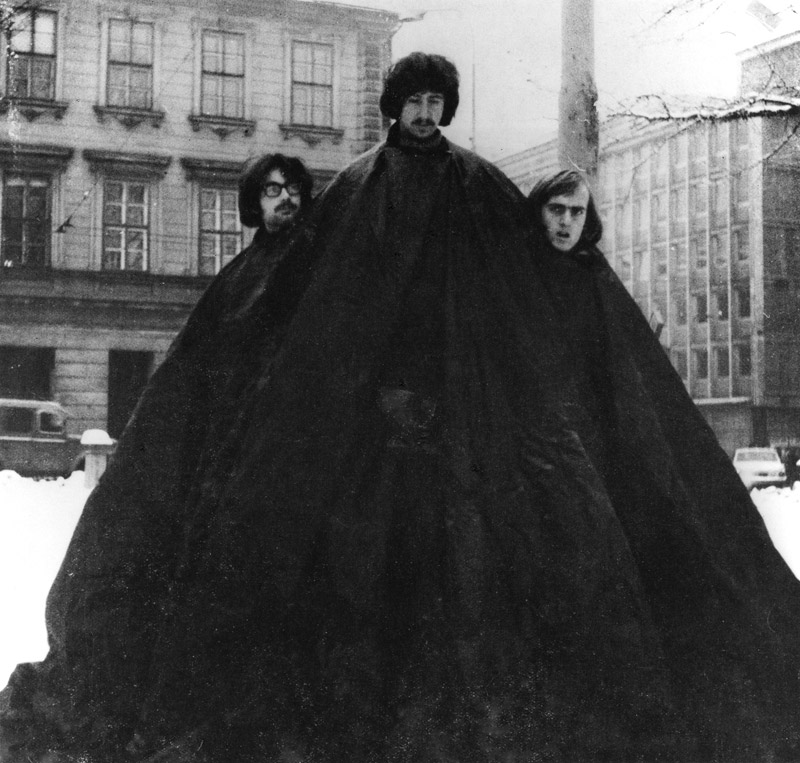

3. Mt. Triglav, 1968, p. 39.

3. Mt. Triglav, 1968, p. 39.

Again, Milenko’s piece. I remember it as one of our more “radical” actions. We sat motionless and silent, and the public (as well as the police) didn’t know what to make of us!

4. Sculptures, 1969, pp. 42, 43.

We decided to do some site specific works in nature, using minimal intervention in the environment. I tied a rock to a tree branch and bent the branch. These works have a “zen” quality, I think, in the sense that the focus is on simple awareness and flowing with nature.

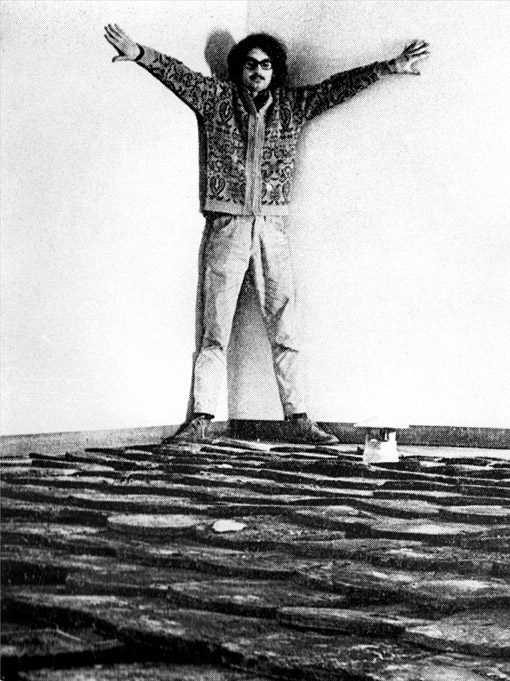

5. The Roof, 1969, p. 48.

5. The Roof, 1969, p. 48.

Part of the Ancestors show. It started as a pure and simple idea of juxtaposing opposites, i.e. above/below = roof on floor. Luckily I was able to find the roofing tiles and get help to carry them up to the gallery. It was a site specific piece as it was a square room in the museum and I put tiles on the floor with enough space to walk around all sides. There was also the association with tradition and age (the old roofing tiles).

6. Soil and Two Planks or Scrap Iron, 1969, p. 51 (both works).

6. Soil and Two Planks or Scrap Iron, 1969, p. 51 (both works).

We were interested in exploring different materials in their raw forms, both natural and industrial. Letting the materials speak for themselves with minimal intervention. The two boards were leaned against the opposing walls of the gallery in site specific manner and held in place with the weight of the earth in the center- basic physics.

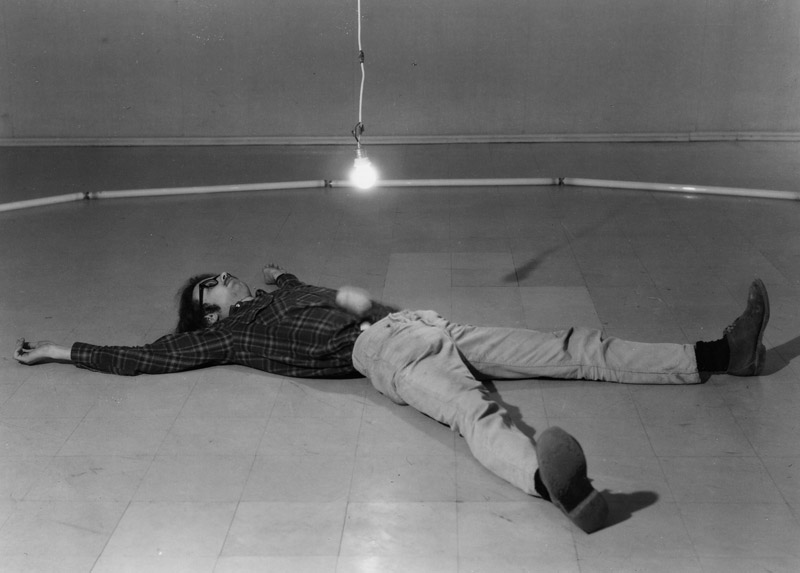

7. Cosmology, 1969, p. 52.

7. Cosmology, 1969, p. 52.

A site specific installation where I took the neon bulbs out of the ceiling of the space and arranged them in a circle on the floor to create a space. I next hanged a light bulb from the center to illuminate the space and was reminded of the solar system, with the sun (light bulb) in the middle. This called for the earth (stone) in the center. I liked the stone as having the opposite quality of glass (hard/fragile). I then did a “body art” performance by lying with the stone on my stomach and breathing for a half hour during the opening. There were associations with Leonardo’s man stretched out in a circle, and the microcosm/macrocosm of hermetic philosophy—hence the title “Cosmology”. Looking back I consider this one of my best works.

8. Mirrors (various projects), 1969, pp. 56, 57.

8. Mirrors (various projects), 1969, pp. 56, 57.

Part of our projects in nature. I was inspired partly by Robert Smithston’s use of mirrors but was interested in exploring landscape photography in a new way by integrating modular sculpture with reflection of the environment. The clay and mirror sculptures were models for larger projects in the landscape, exploring concepts of positive/negative as well as juxtaposing opposites of sky/earth. After photographing them I preferred to let them exist as finished pieces in themselves.

9. Stactometer dropping water in equal intervals on a hot aluminum plate (and similar projects involving different physical transformations), 1969, pp. 66, 70.

It’s alchemical in nature: the union of opposites; water/fire; above/below; and the physical forces of gravity, heat, sound. The water drops formed slowly before they fell on the hot plate, popping and sizzling as they hit the plate. There was also a kinetic or time-based element to the piece that played with the audience’s anticipation. There was a performance element to all the similar projects as they were the residue of the artist’s actions.

10. Projection of Text Over Text on a Wall = Erasure, 1970, p. 71.

Another one of those pieces based on the conjunction of opposites so beloved by the alchemists. The piece is the residue of an action that culminates in it’s own negation.

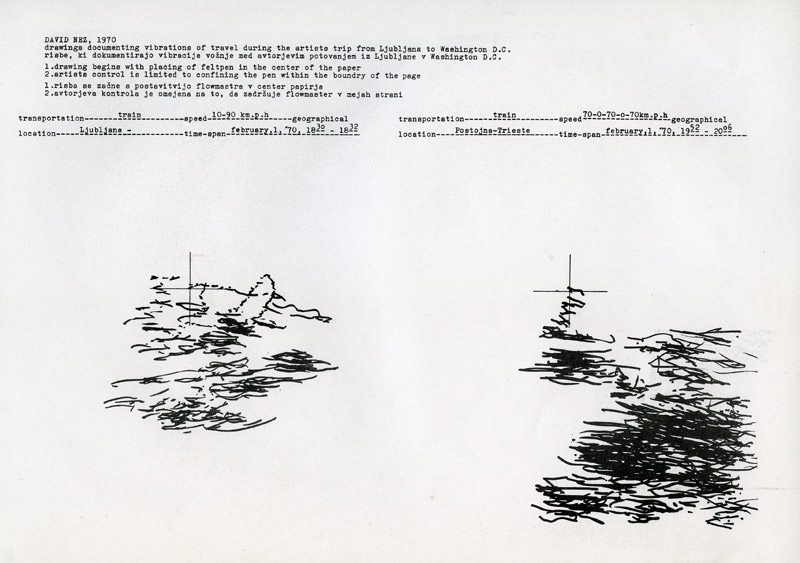

11. Drawings Documenting Vibrations of Travel during Artist’s Trip from Ljubljana to Washington, D.C., 1970, pp. 77-79.

11. Drawings Documenting Vibrations of Travel during Artist’s Trip from Ljubljana to Washington, D.C., 1970, pp. 77-79.

An attempt at redefining the act of drawing as a recording of a temporal- spatial event. A conceptual approach to drawing, recording coordinates of location/time to frame the action.

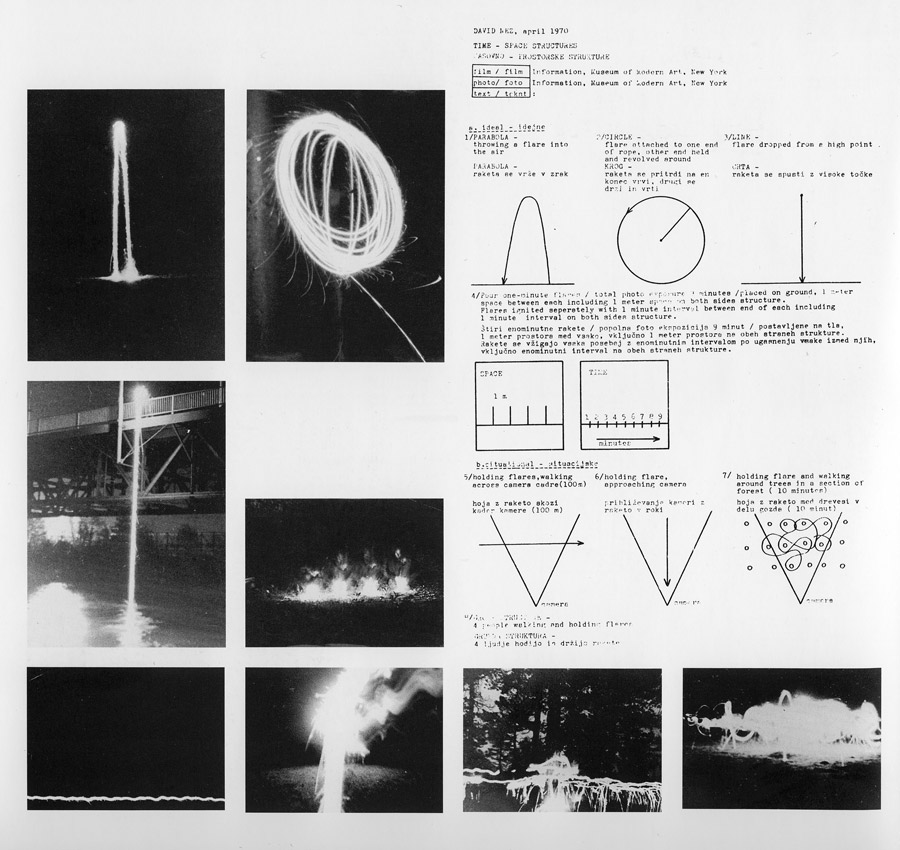

12. Time-Space Structures 1970, p. 94.

12. Time-Space Structures 1970, p. 94.

I was reading Ouspensky at the time. He was a mathematician/metaphysician interested in the “fourth dimension” of time. An attempt to use time-lapse photography to create spatial structures based on process/time to move beyond linear perception to the experience of simultaneity.

BŽ: You mentioned Ouspensky and Smithston. Were there more such influences? How did you find your way to such influences? Were you reading art magazines?

DN: Lots of influences! I was reading mysticism, psychology, philosophy. The most important were writers like AlanWatts (Zen), Aldous Huxely’s Doors of Perception (psychedelic experience), Gurdjieff and Ouspensky (mysticism), Gershom Shalom (Kaballah), Herman Hesse’s Glass Bead Game, Jung’s Man and His Symbols, and others. In terms of artistic influences I was interested in pop art, Duchamp, Dada, surrealism, minimalism, conceptualism, earth art, etc. I didn’t subscribe to art magazines in Ljubljana. I was exposed to some of that art through visits to museums and galleries in New York City and Washington D.C. We got to know Walter De Maria and I visited him a couple times in New York City in the early 70’s. Also I occasionally saw exhibition catalogues at Tomaž Šalamun’s or Milenko’s. I think being on the periphery of the contemporary art scene was a good thing because we had the freedom to do our own thing and not worry about selling work or conforming to art world standards.

BŽ: Did any of the OHO Group works have a special status, was seen as very good already back then?

DN: I don’t think we bothered much to evaluate and critique our work. We were more interested in constantly exploring new approaches. That kept us from repeating ourselves.

BŽ: How did people react to your work? Do you have any special memories?

DN: We got the full spectrum of reactions. Some people loved our work, most ignored us. Some students from the Akademija thought we were just “bluffing;” they were envious or didn’t understand it. In Slovenia a small group of critics like Tomaž Brejc and Braco Rotar were very supportive and encouraging. In Zagreb, Beograd and Novi Sad the critics and art communities were very warm and welcoming. We did most of our exhibits outside of Slovenia! Special memories? There was lots of fun and positive energy, that’s what kept us going. There was also the adrenaline rush of pushing the boundaries and being outrageous.

DN: How do you remember the dissolution of the group? Did you all agree on that? How and why did that happen?

BŽ: I don’t think we ever really dissolved, we just went into a new phase of our personal growth as individuals. Towards the end we became more interested in communal living and sort of “outgrew” the earlier art. Speaking personally, I had graduated from the Akademija and was becoming increasingly focused on exploring spirituality. I lived at Sempas at the very beginning for a while but was eager to travel to India to study meditation. Communal living was an appealing idea and the logical culmination of our earlier efforts, but the idea and the reality were two different things. Living without electricity and running water and the total commitment to collective living was something I was not ready for. I was young and restless and needed to move on with my life and keep exploring.

BŽ: Why did you go back to the USA?

DN: Actually, as I mentioned, I travelled through the middle east and India for a year when I left Slovenia. Following that I lived for two years at the Findhorn community in Scotland before finally returning to live in the USA. After all that traveling I felt a need to settle down for a while to absorb all my experiences as well as re-connect with my cultural roots as an American.

BŽ: Can you tell me something about your post-OHO life?

DN: In 1972 after leaving Sempas I travelled to India. I was interested in learning meditation and visited several ashrams. The most enlightening experience was a Buddhist meditation retreat in Benares where we were locked into a compound for ten days and meditated for twelve hours a day or more. After a week of this, I had some intense personal experiences and breakthroughs that confirmed for me the power of meditation. I had originally planned to live in India for a while but found the “culture shock” too overwhelming. I realized that I couldn’t really fit in; the culture wastoo different.

I returned home to recuperate and to earn more money, and I made the decision of joining the Findhorn community in Scotland where Milenko was living. I lived there for two years, working in the publications department as a graphic artist. At Findhorn I met students and practitioners of many different spiritual paths who introduced me to a holistic worldview seen through a Western perspective of spirituality. I studied different techniques such as astrology, dowsing, and geomancy, working with nature spirits, etc. The highlight of my experience was visiting megalithic monuments, stone circles, and Gothic cathedrals in Scotland, England, and France. I saw that the ancient builders of these monuments had a sophisticated understanding of the subtle energies inherent in landscape, geometry, and art. Realizing how “advanced” they were in terms of living in harmony with the cosmos was a huge conceptual breakthrough for me at the time. Understanding the limits of modernity and of our culture’s alienation from nature and spirituality has remained with me ever since and has driven me to explore alternative as well as traditional forms of art and spirituality.

After returning to the U.S.A. I lived on a farm in Maryland for a couple of years. I started making artwork again, working on site specific installations in natural environments and in gallery spaces, using string, mirrors, bamboo, rocks, etc. that I set up temporarily, documenting it with photos. I explored and expanded the ephemeral time-based installations from the OHO years. I also started to work with performance art at this time, some of them solo but mostly in collaboration, exploring the use of sculptural installations in a performance art context. This was during the Reagan era, and my work became increasingly engaged in a narrative of political commentary that was critical of US foreign policy. In 1981 I returned to graduate school at the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore, Maryland. Influenced by my performance work I began to explore narrative and symbolism in paintings and installations.

After graduating I started working at a local psychiatric hospital, doing artwork with the patients as a therapeutic activity. I was deeply moved by the artwork I was exposed to. My patients had no artistic training and some of them created art that was genuine, raw, and powerfully expressive. I decided to study art therapy, a relatively new discipline that uses art to facilitate the healing process. I attended an art therapy program at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque in the early 1990’s, based on the writings of psychologists Carl Jung and James Hillman, both of whom focused on archetypal symbolism. I have had a lifelong interest in alchemy and was able to study Jung’s writings on alchemical symbolism in depth as part of my studies. Since that time I have worked professionally as an art therapist.

I married my wife Kirsten, a dance therapist, and in the late 1990’s we moved to Portland, Oregon, where we presently live. I have exhibited my artwork in galleries on the East and West coasts for the last two decades. The exposure to my patient’s artwork has influenced my own artistic direction as I have tried to make my work more accessible to the broader public. I have explored “traditional” media such as drawing, painting and sculpture as well as the cultural vocabulary of archetypal symbolism seen through the filter of my personal narrative. In a sense I’ve tried to juxtapose historical tradition and modernity in my work. Alchemy as a metaphor for personal transformation continues to inspire my artwork.

My latest paintings explore images from Renaissance- era alchemical manuscripts and hermetic texts of astrology and magic in combination with modern dictionary illustrations, maps, and scientific diagrams. Even though the formal realization of my work has changed I believe the original creative impulse I discovered during my OHO years continues to drive me. I see my artwork as a continual work of exploration and growth, the physical residue of a personal experiment in conscious evolution.

BŽ: Thank you for this conversation.

[su_menu name=”OHO”]