The Imagery of Power: Bucharest’s City Hall

The following essay is part of a series devoted to contemporary art and architecture East-Central Europe. It was first delivered as a paper at a conference held at MIT in October, 2001.

In the history of Romanian modern architecture there are few themes that may be followed from its evolution, beginning with its dawn at the end of nineteenth century and ending with the rupture brought upon it by the installment of the communist regime after World War II.

One of the most relevant themes, though, concerns the desire to build a city hall in Bucharest, the capital of the country. Due to an unfortunate fate, however, this plan was never followed through to its completion, at least not in the way its proponents had wished that it would.

Perpetually reiterated during the years, it became a sort of locus classicus of modern Romanian architecture. Launched at the end of 19th century as an architectural competition, the idea of building an appropriate city hall for Bucharest was abandoned several times but always resurfaced with renewed enthusiasm and, of course, a renewed conception as well.

Therefore, highly symbolic for a public program, this theme became also a synecdoche of Romanian modern architecture, enabling us to examine the whole through one of its components.

The several projects for a Bucharest city hall are also closely connected with the creation of a single national image in Romanian architecture, one that might trace its development through all the steps of its evolution.

If this theme did become a perfect locus for experimenting with the different approaches to a national style, it happened mainly because of its strong ideological involvement-it was an ideal support for the Imagery of Power.

As national ideology played an essential role in the definition of a modern state of Romania, being promoted as an official doctrine, analyzing the several phases of this theme will allow us to penetrate into the intimate mechanisms of power and politics.

For all these reasons, this case study appears to be a precious instrument in understanding how a national identity in Romanian architecture was shaped.

Before entering into the subject, we need to briefly define the context. At the beginning of 19th century, on its way towards both political and cultural emancipation, Romanian intelligentsia looked for support in Western European civilization, the only culture, in their opinion, able to save Romania from the “barbarian orientalism” imposed by the obedience to the Sublime Porte.

This process was accompanied by a national effervescence-with echoes of the nationalist ideology blazing all over the continent-and so, by the end of the century, a new independent State appeared on the map of Europe; created in 1859 by the unification of the Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, Romania had obtained its independence in 1878 in the war against the Ottoman Empire.

The political victory was also reflected in the cultural field, especially in literature and painting, which were the first art forms to promote a national expression. Architecture followed later in the attempt to create a National style.

Fashionable Western European trends, which had replaced the traditional forms since the beginning of the century, soon infiltrated all architectural programs, and were considered the only possible mark of culture.

As architecture was perceived as the most effective instrument of propaganda, the first king of Romania, Carol the First, from the Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen family, adopted the Beaux-Arts style as the official architecture. The prestige and the grandeur of the style were meant to guarantee the integration of the young State among the old European civilizations.

In this context, in the 1880s there appeared several attempts to create a National style in Romanian architecture, both as a response to the achievement of a national consciousness and as a reaction against the preeminence of foreign models.

Paradoxically, National style was shaped under the influence of foreign stimuli; the young Romanian architects who fathered it were almost all educated at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

Their contact with French culture, particularly with the experiences of Archeological School and the innovative theories of Hyppolite Taine and Julien Guadet, fed their willingness to create a specific architectural expression able to reflect national identity.

This new style, designated as “national” or “Romanian”, was based on a complex dialogue with the local tradition, which was assimilated and interpreted in new schemes. Wavering at its beginning, the National style grew to be a strong movement that dominated the Romanian architectural scene for several decades in the first half of the 20th century.

What defined this emerging current was its keen relationship to national ideology-more than a style, it was a deontology, which explains its longevity in comparison to other architectural trends.

This intimate correlation also explains why the vocabulary and even the inner conception at the basis of National style experienced several alterations during its evolution; what may seem a manifestation of polymorphism is actually a faithful reflection of the changes in the national ideology theories.

At its beginnings, National style was mainly involved in residential programs-the first attempt to create a specific architectural expression was actually represented by a small villa designed in 1886 by Ion Mincu for Ion Lahovary, in Bucharest.

At a time when the official policy sustained Beaux-Arts architecture, the success of National style depended entirely on the enthusiasm of private clients. After the proclaiming of the Romanian Kingdom in 1881, the capital of the country became the theater of a feverish building campaignmeant to create the necessary infrastructure for a modern state.

All the institutions erected in those years proudly displayed the Beaux-Arts aesthetics, granting dignity and magnificence for the capital of the young kingdom.

The last great project of this gigantic building campaign, the Bucharest city hall was the only one to adopt the National style, an act that represented the first major official acknowledgement of the nascent current.

Actually, there was a foreign architect who insisted on the importance of using an architecture inspired by local traditions for the official programs.

Invited in the jury of the international contest of 1890 for the Chamber of Deputies, the German Paul Wallot regretted the uniformity of the projects, which would have fit “as well in Rome as in Paris or Berlin,” as well as the lack of a specific expression, appropriated to the identity of the place. “I think that the contest would have been more interesting and more original,” Wallot said, “if the projects would have been inspired by the elements of Romanian architecture.”(“Primul banchet al arhitectilor români,” in Analele Arhitecturei si ale Artelor cu care se leaga 1 (1891): 15.)

Before that date, the idea of employing an aesthetics inspired by local heritage occurred only twice: once in 1882, when the commission charged with a project for the State Archives demanded the use of a “Byzantine style appropriated to our country,”(See Aurelian Sacerdoteanu, Proiecte pentru Palatul Arhivelor statului. Contributie la istoria arhitecturii noastre în secolul XIX (Bucuresti: Cartea Româneasca, 1940), 3-4.) and then again in 1888, when Ion Mincu, father of the National style, was personally asked by the Minister of Public Instruction to design the Central Girls School in Bucharest.

Nevertheless, none of these occurrences represented real promise. In the first case, the choice of Byzantine style-for at that time National style did not exist yet-was correlated with the shape of the building, which ought to borrow a monastery appearance;(The project was suspended and initiative was open again in 1890 when the Romanian government commissioned the Italian architect Giulio Magni. This second project was also abandoned.) in the second case, the minister was a close friend of the architect, so his official position was supplanted by his private convictions.

Thus, Nicolae Filipescu, Bucharest mayor at that time, can be considered the main official responsible for imposing a national identity in the architectural image of public programs.

By opposing the prestigious Beaux-Arts style in favor of the “modesty” of the local tradition, for an edifice that was to be the symbol for a whole kingdom, the mayor’s choice was an important political statement.

Declaring that he intended to “restore Romanian style” through this edifice, Filipescu very clearly meant to install a National style for a national identity. His commitment also had an emblematic meaning: building the future-the city hall program was entirely new in Romania-upon the strong foundations of the past by reviving traditional local architecture.

In the program of the contest, Filipescu gave a clear description of what he understood to be “Romanian style”: “[The architects] should use judiciously and extensively the characteristic elements of the several periods of Romanian architecture, such as arcades, galleries, columns, porches and balconies made out of wood or stone, belfries, ornamented friezes and balustrades, polychrome ornaments in brick and terra-cotta, etc.”(Monitorul Comunal al Primariei Bucurest 12 (1895): 152-54.)

Stressing the importance of the genuine source of inspiration, the mayor asked the architects to study “monuments and old buildings of the country,” and to produce concrete proofs of documentation. These scrupulous demands were a perfect reflection of the emerging phase of National style, showing the deep eclecticism of its sources and the historicism of its methods.

The profusion of enumeration corresponded to the determination to shape a synthetic image of national identity.

Though there was no clear precision in the text, it was obvious that the mayor favored the early 18th century Wallachian art, considered the most accomplished expression of the Romanian heritage. Called “Brancovan” art, after the name of the prince Constantin Brâncoveanu who played an important role in its creation, the style developed, under the contact with Ottoman and Italian artistic experiences, a Baroquelike abundance of forms and decoration.

The mayor decided on an architectural competition limited to entrance by invitation only. He wanted to invite seven or eight renowned professionals, but finally only three candidates participated: Louis Blanc, a Swiss established in Romania, the Italian Giulio Magni, by that time directing the Technical Department of the city council, and the Romanian George Sterian, convinced militant of the national ideology. Unfortunately, only the projects of the last two demonstrated the vicissitudes of the time.(Romanian scholars considered the three projects lost, but actually only Blanc’s is missing. Ezio Godoli had recently presented Magni’s contribution. See Ezio Godoli, “Architetti italiani nei Balcani tra Ottocento e Novecento”, in Architettura e architetti italiani ad Istanbul tra il XIXe I XX secolo (paper presented at symposium in Istanbul, 27-28 November 1995), 87-95. We have found Sterian’s project published in the French architectural magazine Le Moniteur des Architectes. See “Projet d’hôtel de ville pour Bucarest,” in Le Moniteur des Architectes (1900): 64, plates 45-47.)

Both Magni and Sterian followed the mayors demands, but each of them arrived to a personal image of the “Romanian style”.

Destabilized by the novelty of the program, but also a mediocre architect, Sterian was confusingly prolix, mixing geography and epochs. Considering the early 18th century Wallachian art as a fusion of Romanesque and Venetian influences, he employed the Romano-Byzantine style as a paradigm, which shows that he must have been acquainted with Ruskin’s theories.

He reinforced his national discourse by a series of “literal” quotations from the two most praised historical monuments, the Wallachian Episcopal Church in Curtea de Arges (early 16th century) and the Moldavian Three Hierarchs church in Iasi (the middle of 17th century).(Sterian knew both monuments very well, because he worked as an assistant of the French architect André-Emile Lecomte du Nouÿ who restored them.) He also added two monumental statues-a possible allegory of Romania and an equestrian representation of the national hero, the prince Mihai the Brave, the first to have ruled over Wallachia, Moldavia, and Transylvania.

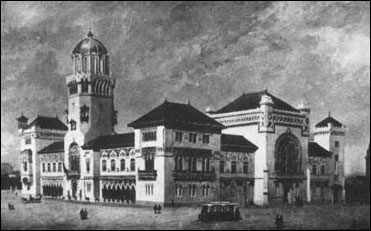

As a foreigner, Giulio Magni was more circumspect in choosing his sources, complying with the theories of local historiography of art. He used as a privileged source the Brancovan architecture, with its accolade arcades and rich decoration, combining it with Italian motives in order to stress its origins.

His composition was coherent, in spite of some incongruities: he associated geminated gothic windows (as in Palazzo Ducale in Venice) with pitched roofs (typical for the Romanian vernacular architecture), as well as a Tuscan campanile with a Byzantine dome.

If the exterior showed a rather comprehensive interpretation of local traditions, the interior displayed a grandiose mixture of Neo-Renaissance and Neo-Baroque: Only the allegoric statue of the prince Mihai the Brave reminded one that this was a Romanian edifice.

Though Filipescu’s initiative was welcomed-the three projects were exhibited and were largely admired-the arrival of another mayor, with a different political orientation, put an end to it.

The idea of a city hall was not completely abandoned, though, and at the turn of the century, another mayor was seduced by it its call. He was the writer Barbu Stefanescu-Delavrancea, famous for his plays inspired by historic subjects and for his activism on the field of nationalism.

Though Delavrancea could have used one of the former projects, he deliberately ignored them and directly commissioned Ion Mincu. His attitude testified an undeniable evolution; he did not need to launch a competition either to define the National style, or to see who was the best architect. He simply chose the best, by charging the creator of the style.

This commission was for Mincu not only an opportunity for a personal affirmation, but also a prestigious occasion for imposing the National style.

In spite of some similarities between Mincu’s composition and the former projects-he followed a scheme very close to Magni’s and chose the same literal quotation of Curtea de Arges portal, as Sterian did-it was obvious that the architect did not inspire himself from these works.

The project proved a high comprehension of local artistic sources and a refined assimilation of their elements. Though the composition was charged, the discourse was clearly articulated both in terms of syntax and morphology.

Mincu developed his specific aesthetics, a combination of Brancovan art with a hint of Moldavian decorative patterns, but also added circumstance elements, in accordance with the symbolic role of the edifice. He used several quotations of the notorious Episcopal Church in Curtea de Arges, and he adorned the main façade with a series of allegoric statues, including the inevitable national hero, Mihai the Brave.

All this extensive national discourse was applied on a scheme of Beaux-Arts inspiration-what might seem a paradox was a mere reflection of that time an emerging national ideology, when foreign patterns were filled in with national substance.

In spite of the enthusiasm aroused by Mincu’s drawings, the project for the city hall was abandoned again and reopened only in 1912, when a young and promising architect, Petre Antonescu, was commissioned with it.

It is a mystery why Mincu was left outside; Delavrancea, now Minister of Public Works, not only did not support his friend, but he showed an obvious preference for the young architect by charging him with the building of the ministry he was ruling.

Mincu’s loyal devotees protested fervently against the new nomination. They vainly carried on their protest even after their master died the same year, proposing that his project be completed by a team of his disciples.

Petre Antonescu was particularly gifted-Mincu himself appreciated him and sustained his debut on the Romanian architectural scene.

Trained at the Ecole, he was very skillful in employing Beaux-Arts aesthetics, but he was commissioned with the Bucharest city hall for his vigorous interpretation of National style.

The choice of the style of the new city hall did not need argumentation in1912; not only had the two previous experiences proved the pertinence of the choice-meanwhile, the National style had gained official recognition through the General National Exposition, opened in Bucharest in 1906.

This event was a triumph for all forms of national ideology, including architecture, and the National style was increasingly employed in the construction of significant public buildings.

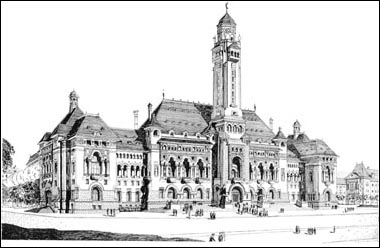

From all the previous projects for the city hall, Antonescu’s is definitely the most consummate. Not only was the architect talented-he had already had the opportunity to refine his approach towards public programs by designing the Ministry of Public Works (1906) and the Prefecture of Craiova (1912).

Both buildings displayed a very personal and achieved style, showing a perfectly mastered and innovative assimilation of the local tradition that he developed as a professor of Romanian art history at the School of Architecture in Bucharest.

The project he designed for the city hall appeared to be more complex than both of these other buildings combined. Though very personal, his scheme was clearly inspired by those of Magni and Mincu; the main façade looks like a superposition of the two projects.

The personal note resided in Antonescu’s interpretation of the National style: The architect used the privileged sources-Brancovan art, gothic elements of the 15th century Moldavian art, motives from the Episcopal Church in Curtea de Arges- and transformed them into a vigorous new language, sometimes evoking memories of Henry Hobson Richardon’s sturdy expressiveness.

Antonescu accorded the same minute attention to the interior, which-even more than the exterior-was a perfect blend of Beaux-Arts style and the interpretation of local heritage.

Due to the Balkan Wars in 1912-1913 and the outburst of the First World War, the project was not completed. Nevertheless, the idea was not abandoned and preoccupied several mayors after the War.

Bucharest needed more than ever a significant building for its city -hall; the city was now the capital of a powerful state, one of the rare nations to have enlarged its frontiers at the end of the war. The treaty of Versailles recognized the most ardent aspiration of the Romanian nation-the unification of all the provinces-and so the Kingdom was completed with Transylvania, Bessarabia, and Bukovina.

Greater Romania, as nationalists proudly designated the country, proclaimed the National style the official architecture, and started a tremendous building campaign, more impressive than that of the end of 19th century.

The unified country needed not only a modern infrastructure, but also a common denominator in order to enhance the national sentiment. Soon, the boom of public architecture was bound to ensure them both.

In this context, in 1925, Bucharest’s mayor of the time, Costinescu, launched a new competition for the city hall. The contest was the result of some scheming machinates; Mincu’s disciples still wanted to impose their master’s project, while other architects were criticising both Antonescu’s and Mincu’s works, thus cherishing the secret hope to obtain a glorious affirmation.

Nevertheless, several architect corps strongly protested, showing solidarity with Petre Antonescu, who had signed a contract with the city council for the edifice. But the new mayor obstinately defended his position,(The First Congress of Romanian Architects, held in 1916 in Bucharest, established that all-important buildings should make the object of an architectural competition; see “Primul congres al arhitectilor din toata tara,” in Arhitectura 2 (1916): 71-76. So, the mayor possibly took advantage of this regulation in choosing to ignore Antonescu’s signed contract.) and finally, the competition took place, with a total of 22 candidates-the increased number proving the success of the idea.

Like his predecessor in 1895, Costinescu took care to define the style to be adopted. He intended the building to be a metaphor of Greater Romania and asked that each of the unified regions be represented. buy dumps

At a time when the National style had gained full maturity and architects did not need guiding in their attempts, the request of the mayor appeared as a purely political statement; the city hall of the capital had to be the federative symbol of the unified country.

Some architects, like the avant-gardist Marcel Iancu, did not hesitate to point out, from an aesthetic perspective, the absurdity of the demand.(Marcel Iancu, “Concursul Palatului Comunal,” in Miscarea literara 12.2 and 13.2 (1925).) None of the candidates of the competition respected this request.(At least, none of the 16 contestants whose projects were published in the magazine Arhitectura. See “Concursul pentru palatul primariei orasului Bucuresti,” in Arhitectura (1925): 43-76.)

Instead, the big majority of the participants referred to Mincu’s and Antonescu’s contributions-in 1925 the first projects were considered lost-as authoritative models. Some of them chose to follow Mincu, others Antonescu, but most of them contrived to combine the language of both projects.

This attitude was rather curious, because at that stage, those adept with the National style had achieved a high degree of skillfulness in manipulating it; meanwhile, the style itself had progressed, in terms of vocabulary as well as expression, since the two works had been conceived.

The obedience towards these two projects proved that they were perceived as paradigms of the architectural idea of city hall, but it also proved a certain block of the creative thinking. Was it because the ideological burden of the task was too heavy? No wonder this second competition did not get to a conclusion; the jury accorded no prizes-it only classified the works into three categories of value, probably appalled by the surprising resemblance of the plates. Play best friv games site.

But even more surprising was the obsolete character of the projects presented by the contestants, which seemed, as was the case for many of them, to belong to a bygone epoch: the approach was too emphatic, the discourse too prolix.

In 1925, the National style was already the object of several experiments toward the renewal of its expression-this was the time when the label of “Neo-Romanian” started to be used in order to distinguish these attempts from the rest of the production.

Only one of 22 competing projects did not fit the uniform image, freely interpreting the traditional sources and daring to add a new reference-a triumph arch as an allusion to the Latin origin of the Romanian nation.

The failure of this competition anticipated the severe crisis that struck the National style at the beginning of 1930s. Suffocated by the production of its epigones, using and abusing outdated historicist approaches, but also confronted with the highly innovative aesthetics of Modernism, the style had to find a new expression in order to survive.

One decade later, in 1935, another contest for the city hall was opened. The new mayor had the antidote against the failure of the former competition: he made no stylistic demand and invited two French architects, Emile Maigrot and Jean Guilbert, to the jury, hoping that their presence would assure an impartial judgement and a result corresponding to the European requirements.

Antonescu’s contract with the city council was again ignored and 13 original projects were presented in this new competition.(There were several numbers avanced: 13 in “Informatii,” in Arhitectura 6 (1936): 17; 14 in Simion Vasilescu, “Declaratie facuta în adunarea generala extraordinara a Corp. Arh. Rom,” manuscript in the Manuscript Department of the Romanian Academy Library, mss. 932; 17 in Radu Patrulius, “Roger H. Bolomey,” in Arhitectura 1 (1982): 48-56.) Unsatisfied with the quality of the participation, the jury asked for a second phase, where only 10 contestants were allowed.

Antonescu decided to present a new project, too, and so he exhibited, at the same time as the regular candidates, his two versions for the city hall.

It was a clever strategy; his new position (he had signed a contract with the city council), new authority (he was now the principal of the School of Architecture), and also the real, valuable quality of his proposal made him the favorite of the public and the press, which harshly criticized the real competitors.

Even the French La Construction Moderne(Emmanuel de Thubert, “Concours ouvert à Bucarest pour l’édification du Palais Municipal,” in La Construction Moderne (14 March 1937), 394-401.) agreed that Antonescu’s project was the best. So, finally, this third contest failed, too.

Unfortunately, there is no record of the projects in this competition-only a second phase project is currently known-but considering the names of the participants,(Only the names of the contestants accepted in the second phase are known: Dan Ionescu, I. Terdan, C. B. Cretzoiu, Roger Bolomey, I. D. Traianescu, and A. Viecelli, M. Pinchis, Horia Creanga and N.Georgescu, Cristofi Cerchez with G. Negoescu and C. Popescu, Octav Doicescu, and C. Jojea. See Simion Vasilescu, “Declaratie facuta.”) it seems that, stylistically, three architectural trends were represented: Modernism, National style, and New Classicism. Antonescu’s two versions were both variations of New Classicism.

The fact that, for the first time, the competition program did not specifically request National style was more than a sign of the profound change that affected the Romanian architectural scene, now opened to a multitude of experiences: this omission showed an alteration of the official ideology.

Actually, a new type of nationalism was emerging, that was in accordance, as the philosopher Constantin Radulescu-Motru, major exponent of the new current, remarked, with the new spiritual order ruling all over Europe: fascism, Hitlerism, and Stalinism.(Constantin Radulescu-Motru, Românismul. Catehismul unei noi spiritualitati (1936), (Bucuresti : Editura Garamond, 1996), 46.)

Therefore, even if National style was still appreciated, especially in its renewed version, its role in the Power imagery was taken over now by New Classicism. All official public programs had adopted these forceful aesthetics that were nevertheless considered to bearing a national significance. When the royal dictatorship was proclaimed in 1938, this architecture would be designated as the “style King Carol II.”

The last issue of 1939 of the magazine Arhitectura published an article entitled “The Palace of the City Hall of the Capital.”

The article presented to its lectors the project to be finally built, which was a third version of the new project exhibited by Antonescu in 1936. In comparison with the two first versions, the architect had introduced some nuances in its language; the differences were very subtle, but significant.

This final version was conceived as a more powerful, on the ideological level, architectural image. The prevailing aesthetics of New Classicism were enriched with more precise references. Most commonly, bursitis is caused by local soft-tissue trauma or strain injury, and there is no infection. Find out about knee bursitis , inflammation of one of the three fluid-filled sacs (bursae) due to injury or strain. Symptoms include pain, swelling, warmth, tenderness, and redness. Read about treatment and home remedies.

On the one hand, Antonescu added evident references to the local architectural tradition; he used the typical open gallery, with columns and arcades, that he treated in a more “realistic” manner, comparing them to the purged language of the composition in order to enhance its ideological significance.

On the other hand, he introduced some diffuse elements that were a suggestion of the Latin origin of the Romanian people, a topic that legitimated by that time an architecture inspired by the Italian experience and understood in its diversity: the silhouette of the tower, reminding one of a campanile, the classical architecture of the tribune, and the columns of the entrance hall, a modern interpretation of the antique peristyle.

The rich polysemy of the edifice was meant to be a synthetic symbol of national identity; this was a perfect example of the authoritarian style Carol II, Antonescu being one of the fervent promoters of its ideology.

As the Second World War began, this project faced the same fate as the others: it was abandoned. This was the last episode of this epic history.

Eventually, Bucharest got its city hall immediately after the war. It was installed in the former building of the Minister of the Public Works; severely damaged by the bombings, the edifice was reconstructed and enlarged by Petre Antonescu, who had designed the original project. It was a double triumph: by perseverance, Antonescu finally succeeded in becoming the architect of the city hall, while National style, in its high expression, became the emblem of the capital.