The Extractive Landscapes of Sammy Baloji

Sammy Baloji: Extractive Landscapes, Stadtgalerie Museumspavillon, Salzburg, July 25 – August 17, 2019

A landscape that has been transformed by human intervention retells the story of the complex power play between different interests and concepts of reality. Such a landscape is never neutral, but rather constantly negotiated and explored, suggesting various interpretations and conclusions. Colonial expansion represented lands outside of the ‘civilized’ European framework as spaces in dire need of cultivation, civilization, and ultimately exploitation, their inhabitants included. Such attitudes continue to affect people in former colonies and beyond. Their material realities have permanently changed by the consequences of colonial exploitation, which continue into the present day. However, these realities are rarely discussed in public discourses driven by liberal concepts of progress and development. The global invisibility of the material, economic, and social damage caused by colonial exploitation is the main issue that artist Sammy Baloji addressed in the exhibition Extractive Landscapes, presented at Stadtgalerie Museumspavillon, in Salzburg.

Stadtgalerie Museumspavillon is located in the Mirabell Gardens in Salzburg, and Extractive Landscapes related to these surroundings, although this relationship was never explicitly addressed by the exhibition or the accompanying curatorial text. The Gardens are an integral part of the Mirabell Palace complex. Their strict geometrical design is impeccable, engulfing visitors in an atmosphere of order and clarity. Their flora is rich and opulent, but it is not allowed to grow unruly and wild. It is cultivated with precision, into strictly bordered segments. Created in the 17th century, the Gardens follow the Baroque postulate of imposing order upon nature; of shaping everything, including landscapes, to fit a human vision of the world. Extractive Landscapes explored the social and political implications of a landscape changed by people, and examined the outcomes of colonial and postcolonial practices of exploitation and appropriation in two provinces of the artist’s native Congo. Mirabell Gardens were made for the visual pleasure of the rich and powerful in the Baroque era. Extractive Landscapes, on the other hand, showed the material circumstances that provided the economic and social conditions for landscapes similar to the Gardens to flourish around Europe in the following centuries.

Born in the Katanga region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Sammy Baloji witnessed first-hand the changes happening in the country. As a Photography and Computer and Information Sciences graduate,(“Sammy Baloji,” Auguste Orts, https://augusteorts.be/about/sammy-baloji (accessed December 24, 2019).) he used the photographic lens to capture the visual manifestations of the economic and cultural changes in his country, and introduced other historical materials into a dialogue with his images. Starting out as a cartoonist, he later transitioned to art photography and video, using these media as tools for the exploration of contested histories in his home country.(Ibid.) In Extractive Landscapes, Baloji exhibited several objects that guided visitors from one critical point to the next, culminating with a video that explained, in more detail, the problems that locals in the country continue to face as a result of colonial manipulation of their land. Focusing on the material aspects of colonial exploitation and changes in the landscape, the exhibition was also reflective of the broader interest in materiality and geography in recent curatorial and theoretical practices, stemming from ecocritical, feminist, and queer interventions in the ways we understand materials, environment, and agency.(See W.J.T. Mitchell, ed., Landscape and Power (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994); Greg Gerrard, Ecocriticism (London and New York: Routledge, 2004); Estelle Barrett and Barbara Bolt, eds., Carnal Knowledge: Towards a ‘New Materialism’ through the Arts (London: I.B. Tauris, 2013); and Rick Dolphijn and Iris van der Tuin, eds., New Materialism: Interviews & Cartographies (Open Humanities Press, 2012).)

Sammy Baloji. Extractive Landscapes. Installation view. Stadtgalerie Museumspavillon, Salzburg. Image courtesy of the author.

The exhibition was installed in three rooms of the Museumspavillon. On the wall immediately opposite the entrance, a large placard described the main ideas of the show. The artist focused on the Katanga and Kivu regions of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and aimed to show the “processes of abstraction and transformation by which local production conditions…are rendered invisible.”(From the introductory placard of the exhibition.) He played with this invisibility directly in the works presented, giving out little information about the conditions that created them. Baloji offered the elements from which viewers could grasp the story about what happened in these regions, but he did not straightforwardly retell it.

This was evident immediately in the first room. On the wall adjacent to the introductory placard, curators Lotte Arndt and Simone Rudolph displayed a lone digital inkjet print titled Mine à ciel ouvert noyéde Banfora #2, Lieu d’extraction minière artisanale (Flooded Open-cast Mine in Banfora #2, Site of Manual Extraction) from 2010. The print of the mine shows the corrugated edges of exploited land, which might at first appear to be an abstract image. However, as the title suggests, the twists, curves, and holes in the land are manmade, and on closer observation the small figures of miners become visible. They are intertwined with the land, working their way up over a small path between overbearing cliffs. We see the changed land, and assume from the title that some type of extraction is happening there, but only after close observation does the image reveal the precarious working conditions of the miners.

Sammy Baloji. Prints of geological maps, 2019. Stadtgalerie Museumspavillon, Salzburg. Image courtesy of the author.

In the second room, a series of maps were attached to the wall with binder clips, in line one next to another, as if taken from a bureaucratic dossier. Selected from a body of colonial and post-colonial geological maps of the Kivu region, their design and presentation lent a feeling of abstraction and detachment. The maps showed segments of the land in bright colors with names and different lines of division crisscrossing them, but any titles or further explanation were lacking. This made immediate readability of the maps difficult –it was unclear from which period each map derived and at times even what part of the land was shown. This information was purposefully omitted, as a critical tool: this approach highlighted how easy it is to impose one’s vision of the world upon a region, and at the same time erase the complexity of meanings and social relations that formerly defined it. The maps, colorful and pleasing to the eye, concealed a more sinister history of divisions tucked away behind a bureaucratic approach to the land. Extractive Landscapes’ underlining theme was the divisions and removal, not just from land, but from traditions, customs, and the usual way of life for people living in the abovementioned regions of Congo. This was fully elaborated by Baloji’s video in the final room, but the second room offered an additional array of visual material from which viewers could further comprehend segments of the story.

In addition to the geological maps, several copper crosses that served as a currency in the Katanga region between the 13th and the 20th century were also exhibited. These were set in a display table next to a book entitled Union Minière du Haut Katanga, 1906-1956 (1956), a historical review of the Belgian mining company that operated in the region and whose activities rendered the crosses obsolete. On the adjacent wall was another print titled Mine à ciel ouvert noyée de Mutoshi (Flooded Open-cast Mine in Mutoshi, 2011), while in front of the large window overlooking the Gardens was an assembly of copper shell casings with different plants growing from them. Positioned to contrast the view of the perfectly designed garden outside, the plants in the gallery were arranged on the floor in an apparently arbitrary fashion. Lastly, to the left of the room’s entrance was a final artefact: a small geometrical drawing depicting the mineral brookite.

Sammy Baloji. Extractive Landscapes. Installation view. Stadtgalerie Museumspavillon, Salzburg. Image courtesy of the author.

Observed together, these disparate objects, drawings, and prints reflected on the greater impact that colonial and post-colonial practices of exploitation and appropriation have on communities and the landscape. From the abstract image of a mineral, to various archival materials and visually engaging representations of the capitalist footprint on the land, the exhibition drew a strong correlation between the materiality that defines the lives of people in Congo and the aftermath of colonialism, which resonates across wider geopolitical relations. The exploitation of land in Congo has directly influenced people’s lives there, but it has also affected broader socio-political and economic relations around the world.

While people in Congo traded in copper crosses, colonizers enforced relations based on the market value of the exploited materials. The technical drawing of brookite, on the opposite side of the room from the crosses, highlights such a disengaged attitude towards resources and land. The minerals that colonizers exploited and processed—and later exported around the world to be used in different appliances and weapons—had value for the locals only when they were shaped into the form of a cross. The colonial race for resources and disinterestedness in customs and traditions they usurped have turned these crosses into the relics of the past. The image of the flooded mine, with its peaceful blue tones and serenity, showed the changed landscape that colonial exploitation created, while leaving the hardship behind this event hidden. The plants installed in copper shell casings were the only objects in the exhibition that directly suggested the violence and damage sustained through new colonial relations at both local and global levels, since the weapons made from the copper sourced in Congo have deadly applications around the world.

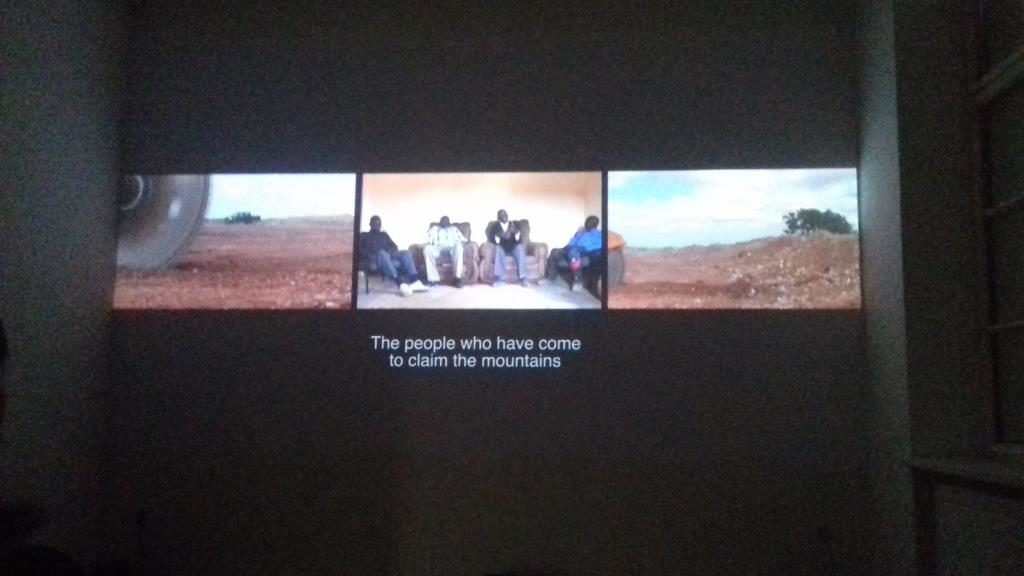

Sammy Baloji. Pungulume, 2016. Video, colour, 29’. Installation view. Stadtgalerie Museumspavillon, Salzburg. Image courtesy of the author.

The last room of the pavilion was dedicated to a three-channel video entitled Pungulume (2016). The video served as a concluding remark on the conditions the exhibition explored by giving the voice to Sanga Chief Mpala, a local chief who had witnessed some of the changes that came with colonization. While Chief Mpala speaks, two other channels show footage of the land: at first undisrupted, green, and paradisical, and afterwards stripped of its greenery, and processed by heavy machinery. Baloji also includes archival black and white video reels of the first colonial processes of extraction, intercutting them with the images of the present moment in the video channels. As Chief Mpala explains, people from the West came and drew new borders on the land, disregarding local traditions and social relations established for centuries there. This narrative was the only segment of the exhibition where viewers could hear the local story, revealing in full—at last—the processes that still affect the people living in the Kivu and Katanga regions.

The geography of a place is decided by many factors –historical, social, political, geological, economic, and ecological. These factors intersect and overlap with power relations defining the lives of people living in that place. Oftentimes it is humanity that shapes landscapes and adapts them so they correspond with a human vision of the world. In Congo, two visions—of the colonizers and locals—clashed in the 20th century and the dominant one reshaped the everyday life of the local community. Sammy Baloji’s Extractive Landscapes eschewed didacticism in presenting this narrative, and also evaded an anthropocentric approach. Instead, the artist and the curators focused on telling the region’s story through a relatively small group of objects and prints that commented on material reality as reflected in the land itself. Baloji combined artistic and archival materials in his installation, leaving the most descriptive piece – Pungulume –for the last room. There, the explanation given by a local chief, brought together the other elements of the show. Viewers might have wandered through the exhibition, merely admiring the colorful display of maps, plants, and prints—until Chief Mpala’s voice explained how all these elements fit together within the complex geopolitical relations. By choosing not to include additional explanations, Baloji and curators punctuated further the issue of invisibility of harsh changes to landscapes and cultural practices induced by colonial and postcolonial exploits. The negative aspects of colonial mineral extractions continue; sometimes they are visible, but more often they are not. Nevertheless, they continue to exert an influence, even if they are well-hidden behind other stories. Artistic interventions into archival materials in combination with original works can bring attention to these aspects, but only if we also actively participate in their revelation—this seems to be Baloji’s message. In the end, it all depends on our ethical position: are we willing to delve deeper into such narratives, or will we remain disengaged from those histories that do not seem to affect us directly at the moment?