The Aesthetics of Economic Migration: nGbK’s Gastarbeiter 2.0 Exhibition

Gastarbeiter 2.0: Arbeit means Rad, at nGbK Berlin, April 13 – June 16, 2024

Jelena Fužinato’s mobile structure Builder’s Daughter: Everything is Peachy stands at the entrance to Gastarbeiter 2.0: Arbeit means Rad, an ambitious new exhibition hosted by the Neue Gesellschaft für bildende Kunst (nGbK). Composed from the same gleaming chrome as all of the installations in the exhibition, the piece takes the form of scaffolding holding a landscape painting of the artist’s home in Prijedor (Bosnia and Herzegovina), which was assembled with the help of a group of hired workers. Able to be freely moved around the exhibition space, Builder’s Daughter is at once a commentary on the inaccessibility of the artworld, and also a spotlight upon the labor of construction work, which is often invisible and regularly underappreciated. The installation thus serves as a framing device for one of the exhibition’s central themes: the shifting understanding of economic migration across generational and educational divides. Such a shift also brings with it a challenge to our culturally produced image of the migrant worker and her struggles.

Jelena Fužinato, Builder’s Daughter: Everything is Peachy, 2024. nGbK Berlin. Image courtesy of Dijana Zadro.

Gastarbeiter 2.0: Arbeit means Rad was produced by a team of curators, including Hannah Marquardt, Bojan Stojčić, Andrej Mirčev, Adna Muslija and Jelena Vukmanović. The nGbK association, which hosted the exhibition, was founded in 1969 through funding provided by the City of Berlin. The entity subscribes to a democratic participatory process that produces exhibitions and public educational programming devoted to critically examining accepted power structures. With nGbK support and additional funding from the Berlin senate, the curatorial team behind Gastarbeiter 2.0 commissioned a host of new works for the exhibition, which were brought into conversation with a series of new versions of some older pieces.

Of course the nGbK – and indeed the contemporary art system itself – is subject to the same whims that govern the flow of economic migration thematized in the exhibition: under the current German government, public funding for cultural work will be cut by 30 per cent in 2025. The nGbK was recently forced to leave its premises in Kreuzberg (where it had been located for more than 30 years), after the building was sold to an investment company. An agreement reached with the City of Berlin then allowed the organization to move into its current space, a former McDonalds in a defunct mall adjoining Alexanderplatz: a portentous backdrop to an exhibition about migrant labor. Hopes of moving into a newly-built pavilion on Karl-Marx-Allee in 2027 together with other cultural institutions were quickly dashed when the new senate, composed of a coalition of the Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU) and Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), cancelled its construction. The recent history of the nGbK space itself, and the curatorial team’s struggle to secure the space and funding, very much reflect some of the themes examined by the exhibition works.

Gastarbeiter 2.0: Arbeit means Rad focuses mainly on the continuity and change evident in different kinds of economic migration through history, and specifically on the new generation of migrant workers hailing from countries of the former Yugoslavia. Underlying this investigation is an argument about art and culture-making as specific forms of work that for migrant artists produce a double precarity. The exhibition booklet divides the exhibited works into four different categories – transfer, symbiosis, body and alienation. These categories highlight various aspects of the transition from socialism to neoliberalism, in which multinational industries, nationalism and corruption coalesce to produce transnational interdependencies of labor power and capital that often result in worker exploitation. The word rad in the name of the exhibition means “work” in Bosnian/Croatian/Montenegrin/Serbian, while in German this same word means “wheel,” attesting to the ways in which work and movement of people and goods across sovereign borders have been intimately connected in the history of the former Yugoslavia. This double meaning is echoed in Mila Panić’s Südost Paket, which greets visitors with its colorful polyester blankets that are ubiquitous across the Balkans, here stuffed into bus wheels. The work appropriates the look of post-Second World War conceptual art but alludes to the fragmented experience of traveling back and forth as a migrant worker.

Mila Panić, Südostpaket, 2024. nGbK Berlin. Image courtesy of Dijana Zadro.

The exhibition initially seems intent on doing a lot of different things, which threatens to dilute its overall message. A common thread, however, gradually becomes evident as works examining migrant labor reveal a dense web of intersecting factors that may at first appear to be unrelated before settling in the visitor’s mind into a coherent whole. Many of the works allude to established artistic movements while also making explicit political references. In Beautiful Paintings, Nadežda Kirćanski’s sumptuous paintings of euro banknotes that are slightly too large – a nod to the uncanniness of Andy Warhol’s 1964 Brillo Boxes – transmogrify into fetish objects to express the longing for the purchasing power and ideological weight of the euro over the Serbian Dinar. Meanwhile, Kemil Bekteši’s Sofra Shqiptare, a hanging sculpture composed of papier-mâché devreci – a ring-shaped bread-pastry – hangs in front of a geometric drawing recalling works of constructivism, which is in fact an abstract map of the migration flows associated with the tradition of bread-baking from Kosovo and Albania – and an ode to his father’s occupation as a baker.

Kemil Bekteši, Sofra Shqiptare, 2024. mGbK Berlin. Image courtesy of Dijana Zadro.

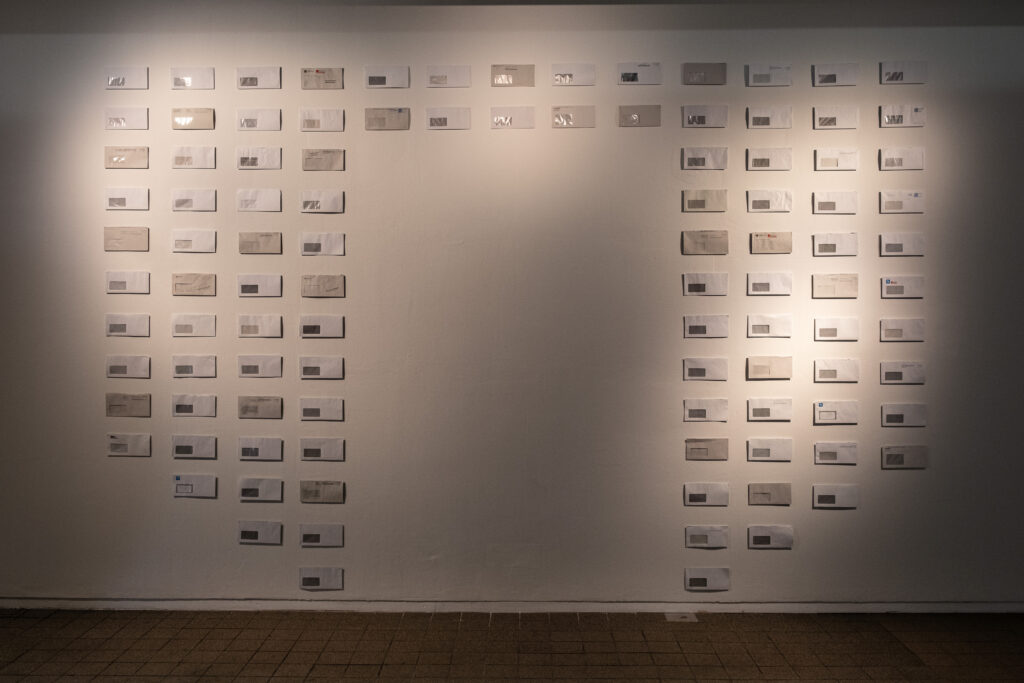

Mounted on the wall in the shape of an altarpiece, and powerfully backlit, is Jelena Vukmanović’s October 2020 – March 2024. Consisting of dozens of empty white envelopes whose little transparent plastic inserts call attention to their bureaucratic nature, this is an assemblage of all of the official mail the artist has received from various administrative bodies during her three and a half years in Berlin. Drawing attention to the invisible labor immigrants must perform to prove their right to live in a foreign country, Vukmanović shows ways in which all immigrants are enmeshed in networks of variable levels of surveillance, while their access to vital services is often severely restricted. The piece is clearly indebted to Serbian artist Tanja Ostojić’s series of works that are associated with an earlier wave of migration from former Yugoslavia, including Illegal Border Crossing and Waiting for a Visa, both performed in 2000, and Looking for a Husband with EU Passport (2000-2005), which provided an institutional critique through the artist’s documentation of the tedious process of legitimating herself within a context of post-socialist transition. Vukmanović’s work carries with it the sense of inevitability, of consistent biopolitical subjugation of the migrant, even in the absence of acute crises.

Jelena Vukmanović, October 2020 – March 2024, 2024. nGbK Berlin. Image courtesy of Dijana Zadro.

In a quiet corner at the back of the exhibition, Nikoleta Marković reflects on the contrasts between her life as an artist and those of the construction workers she observes restoring a façade outside her window every day. Her graphic novel Daily Struggles is presented in the gallery as a video projection of the artist slowly thumbing through the booklet; in front of it is the artist’s desk standing in for the site of her work. Marković also held a workshop with the Gastarbeiter of the first generation, where they recounted their stories. As Bojan Stojčić explains, the current generation of workers is different from those who travelled to Germany and other parts of western Europe as seasonal labourers in the 1960s and 70s. “In Germany, the history of Gastarbeiter from Turkey is well known, but that isn’t the case for the labor force historically coming from Yugoslavia. The first generation of workers didn’t stay in Germany, they would spend certain periods of time there sending remittances home and then return to their countries with enough money to buy a Mercedes and renovate their houses.”(Interview with Bojan Stojčić, April 13, 2024.) Now, in the shadow of the Yugoslav war, the collapse of state socialism and the transition to neoliberalism, there is a new kind of economic migration from the former Yugoslavia to countries such as Germany. “There is even a third class of people,” Stojčić observes, “cultural migrants, who come here because they lack the cultural infrastructure to properly produce art in Sarajevo, for example. But although Berlin is marketed as this liberal Mecca, underneath is a very punishing system.”(Interview with Bojan Stojčić, April 13, 2024.)

Subtending the exhibition is the question of whether migrant culture workers do indeed, as urban studies theorist Richard Florida argues in his influential 2004 book Cities and the Creative Class,(Richard Florida, Cities and the Creative Class (London: Routledge, 2004).) belong to a different class from migrant workers in the construction or service industries. Almost all of the artists in the exhibition have indeed at one point moonlighted as service, construction or technical industry workers – such as Amir Silajdzić, who has regularly created neon installations for other exhibitions and whose Variations of Fritz Cola manipulates found objects in the form of fused Fritz Cola bottles, a product, which is already a knock-off.

In 1994, Andrea Fraser and Helmut Draxler started a working group called “Services” when they started noticing that artists and culture workers were being increasingly called upon to provide multiple unpaid services, such as promotion or cultural mediation, for museums and institutions outside of their own art production. The artists’ aim was to synthesize a “professional model of collective self-regulation” for other artists, thereby challenging the notion of artistic autonomy.(Andrea Fraser, “How to Provide an Artistic Service: An Introduction,” transcribed talk presented at Depot Vienna, October 1994, p. 2.) “Because we are working for our own satisfaction, our labor is supposed to be its own compensation”.(Andrea Fraser, “How to Provide an Artistic Service: An Introduction,” transcribed talk presented at Depot Vienna, October 1994, p. 6.) Adrijana Gvozdenović’s multi-media installation and performance Who is Adrian Lister, takes on these hidden service provisions with lines such as: “The artist must be able to do project management… The artist must be able to do creative consultancy.” This marketing of the self has indeed become something that artists (as well as many other professions in the creative sector) are increasingly forced to perform as part of what Naomi Klein has termed our “doppelganger culture” – our uncanny social media-fuelled mirror world in which we all, to some extent, cultivate our own virtual brand, which can acquire a life of its own and get skewed in sinister ways as seemingly diametrically opposed ideologies merge.(Naomi Klein, Doppelganger: A Trip into the Mirror World (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2023).) Artistic work, then, is a very specific kind of service.

As Stojčić comments, a further important element of the show is that artists from different former Yugoslav countries are being brought together. “In Germany, away from the explicitly ethnonationalist politics back home, you identify with each other, no matter which (former Yugoslav) country you’re from. At home, no one talks about worker’s rights, just identity. Class struggle always includes identity politics, and we include discussions of both in the exhibition.”(Interview with Bojan Stojčić, April 13, 2024.) The sense of community, indeed, was palpable at the exhibition vernissage, which was attended by close to 500 people.

Dejan Marković, Aptiv Syndrome, 2024. nGbK Berlin. Image courtesy of Dijana Zadro.

Another major theme in the show, emphasized in the exhibition text itself, is the toll migrant labor takes on the bodies of workers. Dejan Marković’s Aptiv Syndrome discusses a number of occupational illnesses that have befallen workers, mostly female, employed at automotive and electrical engineering companies located in Serbia. In doing so, Marković highlights the exploitative conditions that too often underpin the supply of technological components to western countries. The large-scale tapestry, which the artist wove with a coalition of weavers from the organization Atelje 61 and workers from the Aptiv, Yura and Leoni factories, using electrical wires, is inspired by a Yugoslav-era socialist realist print of a triumphant worker, but the motif trails off, becoming blurry and nondescript, as if to suggest the present-day inertia of the Yugoslav-era ideals of self-management. Bojan Stojčić’s Die Deutsche Turnkunst is a public performance involving one hundred participants, all of them migrants. As part of this work, the participants perform exercises designed for students by Friedrich Ludwig Jahn – the founder of the German gymnastics (Turner) movement at the turn of the 19th century – which would later be practiced under various totalitarian regimes. The nation is performed through the strengthening of (mostly male) bodies. In his sculptural sendup, Stojčić exposes its absurd chauvinism while subversively inserting migrant bodies into the narrative. Similarly, Alma Gačanin’s Standard Operating Procedure thematizes the “aesthetic labor”(As originally theorized in Chris Warhurst, Dennis Nickson, Anne Witz, and Anne Marie Cullen, “Aesthetic Labour in Interactive Service Work: Some Case Study Evidence from the ‘New’ Glasgow,” The Service Industries Journal 20, no. 3 (July 2000): pp. 1-18.) she has performed as a flight attendant, but her watercolor figures have a menacing reptilian quality that threatens to strike back against harassers.

Bojan Stojčić, Die Deutsche Turnkunst, 2024. nGbK Berlin. Image courtesy of Dijana Zadro.

Alma Gačanin, Standard Operating Procedure, 2024. nGbK Berlin. Image courtesy of the author.

The exhibition shows that, beyond the actual work performed by workers abroad, the attainment of the status of migrant worker is in and of itself a form of work. Furthermore, people who relocate to western European countries to work may find themselves subjected to racism and discrimination, and indeed exploitation as a cheap workforce, as the recently instated EU Blue Cards for “highly skilled” workers from non-EU countries attest.(Andrea Grunau, “Changes to Germany’s skilled immigration rules takes effect,” DW, January 3, 2024.) At the moment, Germany requires approximately 1.8 million additional workers for its labor force;(Reuters, “Half of German companies face labour shortages despite economic stagnation – survey,” Reuters November 29, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/markets/europe/half-german-companies-face-labour-shortages-despite-economic-stagnation-survey-2023-11-29/.) it is therefore perhaps no coincidence that these phenomena are occurring at the same time. As former Yugoslav countries are becoming either EU members or candidates for membership, the imported low-wage menial labor increasingly falls to migrants from the Global South.

Siniša Labrović’s Work on Yourself, which he first performed in 2023 in Ljubljana and recreated for the Gastarbeiter 2.0 vernissage, is about workers being made to perform aesthetically beautiful work (perhaps a sly reference to Marina Abramović’s 1975 Art Must Be Beautiful, Artist Must Be Beautiful). As Labrović contorts his naked body to resemble various famous works – Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893) and Auguste Rodin’s The Thinker (1904)– while gesticulating with a steel hammer and sickle, his inexorable writhing is accompanied by bland techno music. No matter the (state) ideology under which labor is performed, Labrović’s work seems to suggest, the worker is always commodified and, indeed, alienated from the product of his or her labor. A concern for many contemporary artists from the former Yugoslavia is how to recuperate the ideals of antifascism, collaboration and socialism from their hegemonic origins for the present day and for us all. Gastarbeiter 2.0 offers a forum to continue this discussion.

Siniša Labrović, Work on Yourself, 2024. nGbK Berlin. Image courtesy of the author.