The 54th October Salon in Belgrade

ZEPTER EXPO, BELGRADE, 11 OCTOBER-17 NOVEMBER, 2013

The 54th installment of the October Salon in Belgrade focused on feminist and queer interventions in the dominant narratives of knowledge production within patriarchal post-socialist and neoliberal realities. It boldly introduced a variety of artistic expressions within the “Living Archive” framework proposed by the Red Min(e)d curatorial team (Danijela Dugandži? Živanovi?, Katja Kobolt, Dunja Kukovec and Jelena Petrovi?). The concept of “Living Archive” derives from theoretical elaborations of a new, feminist archive in lieu of the standard, conventional systems of archivization and of the traditional archive as a site for normative meaning production. The Living Archive, as described by Biljana Kaši? “is a radical interruption in a main system of meanings and structure of archiving through its disruptive modes of (re)inscribing, coding and decoding…[it is] an open space that means and creates both dislocation and new location, visibility and presence of the invisible, possibility and freedom of experimentation, thereby enabling politicization of space and time.”(Biljana Kaši?, “Thinking Living Archive; ‘Archiving’ the Thoughts or Feminism or?” (Living Archive Notebooks, 2012), 9,12.)

This year’s Salon took place in the former shopping center of Kluz, which was recently transformed into a gallery space named Zepter Expo. Here, the Living Archive took shape in different (non)working interactive stations operating as a malleable knowledge base open to interventions and input from artists and visitors alike. Situated in a room next to the main exhibition space, the stations were: Perpetuum Mobile (with video artworks and different audio, photo and textual documentations); the Audio/Video Booth (on-the-spot recordings and documentation of artist talks, interviews, presentations and debates); the Reading Room (book presentations and an online questionnaire about feminist politics within contemporary art); the Digital Oven (on-the-spot digitization, editing, and uploading); the Forum (a place for discussions and talks); and the Curatorial School (lectures and workshops for writing and the voicing of emerging themes in the field of the contemporary art).

This year’s Salon took place in the former shopping center of Kluz, which was recently transformed into a gallery space named Zepter Expo. Here, the Living Archive took shape in different (non)working interactive stations operating as a malleable knowledge base open to interventions and input from artists and visitors alike. Situated in a room next to the main exhibition space, the stations were: Perpetuum Mobile (with video artworks and different audio, photo and textual documentations); the Audio/Video Booth (on-the-spot recordings and documentation of artist talks, interviews, presentations and debates); the Reading Room (book presentations and an online questionnaire about feminist politics within contemporary art); the Digital Oven (on-the-spot digitization, editing, and uploading); the Forum (a place for discussions and talks); and the Curatorial School (lectures and workshops for writing and the voicing of emerging themes in the field of the contemporary art).

Through the use of these stations, the Salon discursively opposed the traditional conceptual immobility of an art exhibition and offered, instead, an open and fluctuating one that could adapt to changes that came its way from the outside. In line with theorist Rosi Briadotti’s take on “feminist sustainability” that is grounded in discursive subjectivity, the exhibition was in constant interaction with artists and visitors, creating a critical knowledge base in which stereotypical and imposed normative positions can be contested.

By “feminist sustainability,” Braidotti means the “regrounding of the subject in a materially embedded sense of responsibility and ethical accountability.”(Rosi Braidotti, Transpositions: On Nomadic Ethics, (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2006), 137.) At the Salon, such a subjectivity, singular but also outwardly linked to its surroundings, could be glimpsed not only in the exhibition’s conceptual framing but also across different artistic and discursive practices that aim to rethink (non)human nature in relation to the animal, the machine, and non-normative models of existence as a driving force of liberation from patriarchal power and its ideologies; more generally, they move towards new forms of social imagination and responsible politics.

Spreading over three floors of the gallery, the Salon started from the bold premise that patriarchal ideology can be dismantled through art – more specifically, art that practices social engagement, critique, and transformative creativity. Feminist spaces of intervention through art are not solely limited to female or queer repositioning, they also engage with issues such as ecology, social struggles, or employment policies in order to showcase, question and problematize the ways we perceive, interact with, or ignore such issues in our everyday lives.

The Salon’s focus was contemporary feminist art from the region of former Yugoslavia (with a few exceptions). The curators aimed to address the conceptual and political implications of feminism and feminist art within broader socio-political contexts, but they also tackled some of the pressing issues in contemporary art practice, such as the hyper-production of art. Within the local setting of Belgrade, the Salon’s curators engaged with some current problems that are more specific to art production in post-Yugoslavia, such as the lack of funding transparency or the imposition of political agendas that often goes hand in hand with this lack of transparency.

In the show, social reality is investigated through images and narratives that probe sedimented gender positions and political expediency, offering a series of complex art gestures within the regional but also the global art scene. A bitter narrative is presented by Croatian artist Milijana Babi? who, unable to find a job, decides to investigate the labor market for women during the transitional period of Croatia’s accession to the European Union. In her work Artist Looking for Any Kind of Job (2011/12), Babi? shows a series of video, audio and written documents of her unsuccessful short-term jobs—from selling flowers in nightclubs to being a waitress and a cleaner, among others. Themes such as the low salaries paid to workers, harassment, and exploitation recur in Babi?’s work, which aims to show the brutality of the neo-liberal labor market.

The same topic returns in the work of Ines Doujak. While Babi? examines her own position as a female artist within the contemporary market system, Doujak addresses the textile and clothing industry from the position of gender and post-colonialism. In her powerful work Loomshuttles/ Warpaths (2010), Doujak gives insight into the exploitation present both in colonial and post-colonial economic systems, contesting some of the well-worn narratives that circulate in this sector of the economy. The installation, which consists of textile prints and posters, focuses on the history of Andean textile production that Doujak uses as a lens through which she observes the exploitative trade relationship between Europe and Latin America, as well as “the structurally undervalued quality of the feminine and the work of women.”(Loomshuttles/ Warpaths. http://www.inesdoujak.net/lswp/ (acessed Febuary 14, 2014).)

A similarly critical gesture of tying normative narratives to female work and family stories is found in Gozde Ilkin’s embroideries entitled There are Too Many Stones (2012). Made from objects generally linked with family households, such as tablecloths, curtains, and duvets, they question current social and political relationships in Turkey, setting up a subtle critique of established norms and social relations created with materials that within patriarchal societies are often reserved for and/or produced within or for the private and isolated spheres of female existence.

A similarly critical gesture of tying normative narratives to female work and family stories is found in Gozde Ilkin’s embroideries entitled There are Too Many Stones (2012). Made from objects generally linked with family households, such as tablecloths, curtains, and duvets, they question current social and political relationships in Turkey, setting up a subtle critique of established norms and social relations created with materials that within patriarchal societies are often reserved for and/or produced within or for the private and isolated spheres of female existence.

A critique of art historical discourse is the focus of video installation Me, You and Everyone I Know (2010-13) by Priština-based artist Flaka Haliti. Art discourse often allocates to female and male artists a certain set of attributes. While female artists are usually described as successful, they are often excluded from normative discourses. Male artists, on the other hand, are described as masters, their achievements are celebrated, and their position is one of power. As a way to illustrate and criticize this hierarchical structuring of the art world, Haliti uses two diagrams made of combined triangular forms. Each diagram displays a set of attributes associated with either female or male artists. In the video, the constant rapid oscillation from from one diagram to another makes both hard to read, hinting at the difficulty of stabilizing such positions, and the necessity for changing them.

In the video installation Between the Waves (2012), Indian artist Tejal Shah shows her interest in ecology, sexuality, and nature. In Belgrade, this work was displayed as a two-channel installation. While one channel shows dancers dressed in white costumes repeating highly stylized dance movements in a landfill, the other one more closely follows the artist’s interest in sexuality, spirituality and post-porn theories, again with strong ecological concerns. In the second video, two women clad in strips of white fabric and with unicornlike white horns attached to their heads are involved in sexual explorations. Referring to the mythological figure of the unicorn, the installation—filled with amalgamated plastics, CDs, and other industrial debris—shows the journey of two “humanimals” through a dystopian postmodern world where spirituality and sexuality are freed from the traditional rules that govern our society.

Another ecologically conscious work with a focus on normative geographies is Marko Peljhan’s and Matthew Biederman’s installation Arctic Perspective Initiative: Sea, Tundra and Ice Papers (2011). Following the work of the international group Arctic Perspective Initiative that aims to empower Northern and Arctic people through “open source technologies, applied education, and training,” the installation—made of prints and laser-etched glass panes—displays Arctic and Northern regions through traditional mapping strategies and with place names derived from Inuit culture.(Arctic Perspective Initiative, http://arcticperspective.org/ (accessed December 16, 2013).) It opposes colonial, resource management-based cartography and instead offers a different strategy for memory building and cultural geography, outside of the colonial context. As the artists state in the Phoenix Declaration, “the Arctic, its peoples and their cultures, its wildlife and its environment shall continue to exist peacefully and shall not continue to be the scene or object of colonization, natural resources exploitation and international discord.”(From the text panel of the installation.)

Systems of meaning production and their contestation inform the works of the 54th October Salon throughout. In her work A|symmetry (2013), Nataša Teofilovi? supplies a visual metaphor for this complex process. In her 2D and 3D animation, she uses a part of a human body—an arm—, and through its mirroring, rotation, and multiplication creates complex ornamental forms, with the arm gaining its significance through its incorporation into an intricate structure.

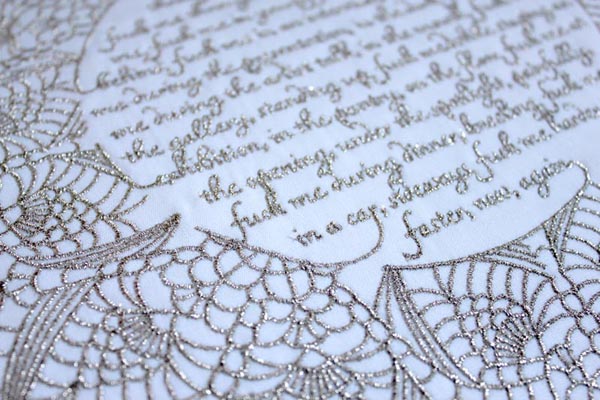

The award of this year’s Salon was divided between four female artists: Flaka Haliti, Lana ?maj?anin, Adela Juši?, and Andrea Palašti, who also received the money award for her installation Balkan Disco (2010-12). ?maj?anin’s 166987 Pricks (2012-13), an embroidery, explores sexual power and domination in a medium traditionally linked with female work. Here, the artist stiches a narrative of sexual control, submissiveness and exploitation on a white fabric, creating a glaring contrast between the explicit language of the embroidered text, on the one hand, and the delicacy of its execution, on the other. A similarly strong contrast between visuality and, in this case, sound, is present in Juši?’s Ride the Recoil (2012). Coming from Sarajevo, Juši? criticizes the exploitation, abuse, and fabrication of history in contemporary war video games. In Ride the Recoil she focuses on the video game Sniper: Ghost Warrior 2 in which American snipers are defending Sarajevo during the 1990s siege. The sound of the game, with a female voice giving instructions to the player on how to kill more efficiently, contrasts with sequential images of a little girl in a street, creating a disturbing contrast between violence and innocence.

The award of this year’s Salon was divided between four female artists: Flaka Haliti, Lana ?maj?anin, Adela Juši?, and Andrea Palašti, who also received the money award for her installation Balkan Disco (2010-12). ?maj?anin’s 166987 Pricks (2012-13), an embroidery, explores sexual power and domination in a medium traditionally linked with female work. Here, the artist stiches a narrative of sexual control, submissiveness and exploitation on a white fabric, creating a glaring contrast between the explicit language of the embroidered text, on the one hand, and the delicacy of its execution, on the other. A similarly strong contrast between visuality and, in this case, sound, is present in Juši?’s Ride the Recoil (2012). Coming from Sarajevo, Juši? criticizes the exploitation, abuse, and fabrication of history in contemporary war video games. In Ride the Recoil she focuses on the video game Sniper: Ghost Warrior 2 in which American snipers are defending Sarajevo during the 1990s siege. The sound of the game, with a female voice giving instructions to the player on how to kill more efficiently, contrasts with sequential images of a little girl in a street, creating a disturbing contrast between violence and innocence.

Palašti’s installation Balkan Disco (2010-12) engages with the diasporic cultures of the Balkan nations and their performance of nationhood and gender within the context of a nightclub. Often associated with good times, Balkan disco—a name sometimes used by nightclubs in Western Europe—is a place where the cultural tropes of the 1990s linger. Through the use of private photographs taken in such clubs, Palašti encourages us to rethink the ways in which anthropological and cultural research in representation, identity and politics is carried out.

Palašti’s installation Balkan Disco (2010-12) engages with the diasporic cultures of the Balkan nations and their performance of nationhood and gender within the context of a nightclub. Often associated with good times, Balkan disco—a name sometimes used by nightclubs in Western Europe—is a place where the cultural tropes of the 1990s linger. Through the use of private photographs taken in such clubs, Palašti encourages us to rethink the ways in which anthropological and cultural research in representation, identity and politics is carried out.

The name of the 2013 Belgrade Salon, No One Belongs Here More Than You, hinted at the curatorial team’s general objectives—to open an exhibition space for feminist interventions that are non-restrictive and not bound by normative politics. Starting from the premise that the feminist archive and the process of archiving should remain open and in constant critical dialogue with everyday realities, the Salon offered a glimpse into a growing field of feminist art in post-Yugoslavia as well as wider global contexts. The Salon’s open and “living” framework invited visitors to critically engage with different subjectivities and narratives that are often marginalized in normative discourses, creating an interactive knowledge base to which all can contribute, and which belongs to no one more than you.