Tanja Ostojić’s Aesthetics of Affect and PostIdentity (Series “New Critical Approaches”) (Article)

The following is the first in a series of essays that explore new critical approaches to art from East-Central Europe.

Tanja Ostoji? is a contemporary Serbian artist who is no stranger to problems of identity. In her work she questions and challenges power relations and their permutations within the realms of politics, culture, and art. Ostoji?’s work spans more than ten years and encompasses a variety of artistic engagements, from performance works in which she covered her naked body with marble dust and stood in the middle of an art gallery, to works such as I’ll Be Your Angel in which she accompanied 49th Venice Biennale curator Harald Szeemann as his escort. As a performance artist of the younger generation, Ostoji? successfully navigated the perilous and turbulent 1990s in Serbia when the country was gripped by armed conflict and immersed in the transition to a Western-style democratic socio-political system. Like several earlier-generation performance artists such as Marina Abramović or Milica Tomi?, Ostoji?’s work touches on the intersection of the body, politics, ideology, and representation. However, unlike Tomi? or Abramović – whose works deal with aspects of identity related to the media, to the legacies of communist ideology, or the new capitalist mass culture – Ostoji? more intimately engages her body, bringing to light the redistribution of libidinal desire into the socio-cultural realm. Ostoji?’s work questions the positioning of the female body within powerful networks of public exchange such as immigration bureaus, welfare offices, schools, international art organizations, and other institutionalized spaces. Although all of these networks are supposedly spaces in which women are equal and free (at least in the West), Ostoji? shows time and time again that these are actually constructs — pointing out that even in the West’s most liberated spaces, women’s bodies are always already placed in a category, marked as transgressional and in some cases even as pornographic.

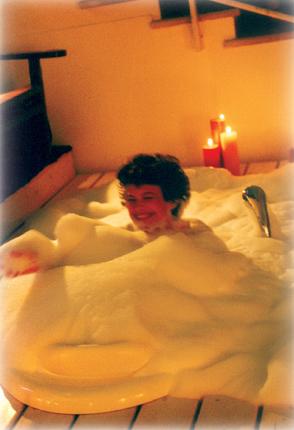

The questioning of identity is one of Ostoji?’s primary goals, and her work can be understoodas queering the very notion itself. Slovenian theorist Marina Grzini? has argued that queer “is ‘that’ something in-between gender and sex that allows us to say that something is not quite right, neither woman nor man, and that connects both toward a radical positioning of life and the medium, art and culture.(Marina Grzini?, “Queer Politics: Identity, Sexuality and Europe.” Journal For Politics Gender and Culture 2, Winter (2003), 64.) Along these lines, Ostoji? performs an almost Deleuzian de-territorialization of identity. Two works in particular, After Courbet L’origine du Monde (poster, 2004) and Be My Guest, a performance and video work from 2001, showcase Ostoji?’s constant reversal of familiar categories. For the performance Be My Guest (2001) the artist rearranged the floor of the gallery Pallazo delle Esposioni in Rome, placing a hot tub in the middle of the room. The invitations she sent out for the show announced that it would be an informal gathering with food and drinks. What awaited the visitors when they arrived at the gallery, however, was something quite different – Ostoji? was sitting in the hot tub together with the show’s curator Bartolomeo Pietromarchi. Food was served at the tub while Ostoji? and Pietromarchi, both naked, proceeded to engage in what appeared to be sexual games.

The questioning of identity is one of Ostoji?’s primary goals, and her work can be understoodas queering the very notion itself. Slovenian theorist Marina Grzini? has argued that queer “is ‘that’ something in-between gender and sex that allows us to say that something is not quite right, neither woman nor man, and that connects both toward a radical positioning of life and the medium, art and culture.(Marina Grzini?, “Queer Politics: Identity, Sexuality and Europe.” Journal For Politics Gender and Culture 2, Winter (2003), 64.) Along these lines, Ostoji? performs an almost Deleuzian de-territorialization of identity. Two works in particular, After Courbet L’origine du Monde (poster, 2004) and Be My Guest, a performance and video work from 2001, showcase Ostoji?’s constant reversal of familiar categories. For the performance Be My Guest (2001) the artist rearranged the floor of the gallery Pallazo delle Esposioni in Rome, placing a hot tub in the middle of the room. The invitations she sent out for the show announced that it would be an informal gathering with food and drinks. What awaited the visitors when they arrived at the gallery, however, was something quite different – Ostoji? was sitting in the hot tub together with the show’s curator Bartolomeo Pietromarchi. Food was served at the tub while Ostoji? and Pietromarchi, both naked, proceeded to engage in what appeared to be sexual games.

Grzini? argues that such “marriages” of art and sexuality constitute instances of what she calls “over-identification”.(Grzini?, “Queer Politics,” 73.) By engaging in displays of sexuality on the gallery floor, Ostoji? pushed the fantasies around art production and its institutional power games to their limit. What is even more important is that her openly sexual behavior involved the curator of the show, a fact that turned the relationship between the artist and the curator into a sort of fantasmatic game. Ostoji? stages her own becoming-one with the curator and also with the audience. The act of simulated copulation is an act of becoming other. In this way the female Eastern European artist who operates within the hierarchical context of the Western gallery institution inverted the usual “order of things.” The blatant sexuality deployed by Ostoji? questions power relations in an uncompromising, political way, and in a setting in which the male Western curator usually has the upper hand. Instead of watching a show, audience members become participants in a group sex act, and the gallery space and the curator are reduced to mere props for the artist who acts out the reversal of their roles. If this brings to mind artists such as Andrea Fraser, Ostoji? brings an additional element to the equation, namely her position as an Eastern European female artist. Her Eastern European background further complicates the curator-artist relationship by exposing the often patronizing attitudes that the West has towards the East.

As Grzini? argues, another important element of Be My Guest is Ostoji?’s strategy of “incarnation”, by which she means the way in which the audience, departing from its usual voyeuristic position, becomes the artist’s lover. At one point during the initial performance of Be My Guest, art critic Ludovico Pratesi jumped into the tub, finally crossing the sacred threshold between the artist and the critic with his own flesh. By destabilizing her own role within the gallery space and by refusing to conform to a script, Ostoji? destabilizes the roles of the other players, as well. Through these transgressions of the norm, Ostoji? creates what Deleuze called a figure. Although his Logic of Sensation is a text written about the traditional medium of painting, it touches upon some of art’s more universal qualities as well. In his description of Bacon’s work, Deleuze uses the term figure to describe the ways in which the artist’s work traverses the strictly representational apparatus of Western painting by passing to the viewer the force of sensation. Through the exchange of forces between different bodies (the body of the artwork, the body of the artist, and the body of the viewer), an artwork produces a kind of spasm, an instance of becoming something else: “The body exerts itself in a very precise manner, or waits to escape from itself in a very precise manner. It is not I who attempts to escape from my body, it is the body that attempts to escape from itself by means of … in short, a spasm: the body as plexus, and its effort or waiting for a spasm”.(Gilles Deleuze, Pure Immanence: Essays on a Life, transl. Anne Boyman (New York: Zone Books, 2005), 15.) It may be argued that Tanja Ostoji?’s works become a Deleuzian plane on which an array of forces multiply and complicate, and the term figure could describe the transmission of these forces to the viewer. Unlike Bacon, however, Ostoji? creates the figure through her own body, drawing the audience deeper and deeper into a shared experience that offers no place for spectators, only for accomplices. In this respect Be My Guest might be viewed along the lines of performance projects such as Guillermo Gómez-Peña’s La Pocha Nostra.

Ostoji?’s poster After Courbet: L’origine du Monde addresses the problem of immigration and the sex-trade with women from Eastern Europe. Most importantly, the work mounts a critique of the ways in which these women and their bodies are codified and labeled within a Western European context. Additionally the work addresses the history of art by quoting a famous (dead male) artist. Ostoji?’s original installation of After Courbet: L’origine du Monde consisted of a large poster foregrounding the lower portion of the artist’s torso. The poster was exhibited on a number of billboards in Vienna and in a park in the Austrian city of Graz. Unlike in Courbet’s painting, Ostoji?’s body is not nude; rather, she is wearing panties in a recognizable shade of blue with the twelve stars of the European Union prominently displayed on her pubic area.

Ostoji?’s poster After Courbet: L’origine du Monde addresses the problem of immigration and the sex-trade with women from Eastern Europe. Most importantly, the work mounts a critique of the ways in which these women and their bodies are codified and labeled within a Western European context. Additionally the work addresses the history of art by quoting a famous (dead male) artist. Ostoji?’s original installation of After Courbet: L’origine du Monde consisted of a large poster foregrounding the lower portion of the artist’s torso. The poster was exhibited on a number of billboards in Vienna and in a park in the Austrian city of Graz. Unlike in Courbet’s painting, Ostoji?’s body is not nude; rather, she is wearing panties in a recognizable shade of blue with the twelve stars of the European Union prominently displayed on her pubic area.

What adds to the work’s effect is the reception it garnered when it was first displayed: the poster was immediately pronounced pornographic and a weeks-long scandal ensued. As Ostoji? herself noted, it was ironic that there was absolutely no nudity in the image. Indeed, it does not even compare to many more explicit images that circulate every day in the mass media. The reasons for the poster’s reception in Austria, therefore, can only lie in the affective play that it created between the artist’s sexuality and the public space it inhabited. The poster’s explicit and political linking of sexuality and nationhood offended the public. More than just a representation dealing with the libidinal relationship between sex, identity, and nationhood, the larger-than-life billboard semmes to have extended out from its narrow frame, subsuming the space around it into its bold content. Its enormous Eastern European vagina stood as an unavoidable reminder of the numerous Eastern European women (as well as women from other non-Western countries) who are abducted or tricked into illegally crossing the border between Eastern Europe and Austria to either work in Western European brothels or as servants, earning minimal pay in slave-like conditions.

In After Courbet: L’origine du Monde Ostoji? mobilizes affect by turning the viewer’s body both into a site of its production and reception. Affect is the connecting line between the work, the artist, and the viewer. Ronald Bogue has argued that affect is an instance of “becoming other” (Deleuze) through which artists are able to “render palpable in the work of art the impalpable forces of the world.”(Ronald Bogue, Deleuze on Music, Painting and the Arts. (New York and London: Rutledge, 2003), 165.) Among the more formal or technical (non-representational) elements of Ostoji?’s use of affect are cropping, lighting, and color. These non-representational signs/codes move us, but we are not sure why. Brian Massumi calls affect an event that is ultimately about intensity. Indeed, the formal elements that structure Ostoji?’s poster – her close cropping of the body, the choice of underwear, the mimicking of canonical artwork, and the image’s size – build a series of supra-cognitive events that entice intense, even physical responses in the viewer. “The body doesn’t just absorb pulses or discrete stimulations; it infolds contexts, it infolds volitions and cognitions that are nothing if not situated,”(Brian Massumi, “The Autonomy of Affect,” 30.) Massumi writes. Following Massumi’s argument we might say that that the specific formal elements Ostoji? deploys in her poster create zones of intensity that, in turn, function in our own in-between spaces, spaces where our cognitive side has not yet understood what the body has already absorbed. More importantly, the fact that Ostoji? image is sexual in nature makes this supra-cognitive reception even more potent, as the viewer finds himself always already a part of the Other the poster depicts – that is to say, the vagina itself. Perhaps this subconscious functioning of the poster was one of the reasons why the work was publicly denounced in such a ferocious way.

Beyond that, After Courbet: L’origine du Monde creates a kind of formal push and pull as we are invited to “enter” the work, but are also pushed out of it by its overwhelming size and taboo subject matter. This formal push and pull of forces makes the viewer highly aware of the texture of the work. Richard Dyer argues that it is in the nature of non-representational signs to be iconic. Instead of a signifier and the signified being related in terms of any sort of physical resemblance, their relationship in non-representational signs is established through structural resemblance.(Dyer, “Entertainment and Utopia,” 20.) This means that viewers make their way in and through the work by relating to the structural properties of the feeling it produces – its affect- rather than by way of any clear resemblance to recognizable visual signs.

This brings me to the ways in which Ostoji?’s work functions in the realm of the so-called relational aesthetic. With her interventions in various public spaces, the viewer is immersed into the art object and she or he becomes involved with its affect. An artistic practice employing this strategy is inevitably embodied, it stands against traditional epistemology. Relational aesthetics calls for a critique of the self-contained subject that ultimately shatters the binary opposition of subject and object. In The Transmission of Affect, Theresa Brennan argues that affect can be seen as a critique of the Western epistemological and metaphysical philosophies whose many embodiments throughout the centuries have focused on the individual, autonomous subject whose emotional life is strictly self-contained. As Brennan writes, “we are…peculiarly resistant to the idea that our emotions are not altogether our own.”(Teressa Brennan, “Introduction,” Transmission of Affect (Ithaca & London: Cornell University Press, 2004), 2.) Social in its origins, the transmission of affect through what Brennan calls the “sharing of emotions” can be both biological and physical. Ostoji?’s billboard plays precisely with this relationship between the political and the affective, placing itself in a social relationship with the viewer by pulling him or her into the folds of the work. Because of its size and placement in a public space, After Courbet: L’origine du Monde extends into the viewer’s space, into real space.

This brings me to the ways in which Ostoji?’s work functions in the realm of the so-called relational aesthetic. With her interventions in various public spaces, the viewer is immersed into the art object and she or he becomes involved with its affect. An artistic practice employing this strategy is inevitably embodied, it stands against traditional epistemology. Relational aesthetics calls for a critique of the self-contained subject that ultimately shatters the binary opposition of subject and object. In The Transmission of Affect, Theresa Brennan argues that affect can be seen as a critique of the Western epistemological and metaphysical philosophies whose many embodiments throughout the centuries have focused on the individual, autonomous subject whose emotional life is strictly self-contained. As Brennan writes, “we are…peculiarly resistant to the idea that our emotions are not altogether our own.”(Teressa Brennan, “Introduction,” Transmission of Affect (Ithaca & London: Cornell University Press, 2004), 2.) Social in its origins, the transmission of affect through what Brennan calls the “sharing of emotions” can be both biological and physical. Ostoji?’s billboard plays precisely with this relationship between the political and the affective, placing itself in a social relationship with the viewer by pulling him or her into the folds of the work. Because of its size and placement in a public space, After Courbet: L’origine du Monde extends into the viewer’s space, into real space.

As an artist Ostoji? engages both the social and the political in order to prove that affect is (also) political and that it eludes regular systems of commodity exchange and the art market. In Ostoji?’s art, which often picks a libidinal fantasy as its organizing element, the viewer’s surrender to affect implies the surrender to affect’s often controversial politics. Ostoji? produces visibility and political engagement through a careful complicity with and complicated positioning of the artist’s body in relation to both the audience and the networks of art and power within which work and audience encounter one another.

Further reading in the “New Critical Approaches” series:

Andrey Kuzkin, Conceptualist Son (Article) by Yelena Kalinsky

Performatism in Contemporary Photography: Alina Kisina (Article) by Raoul Eshelman