Suspended Belief: On Art and Memory in Hungary

In 2007, at the Venice Biennial, Andreas Fogarasi’s Kultur und Freizeit (curated by Katalin Timár) received the Golden Lion award for the best national pavilion. The work dealt with the socialist cultural houses and remnants of socialism in a video installation. Fogarasi is Hungarian, based in Vienna and in his early thirties. According to a logic typical of secondary memory or “post-memory”, this young artist “remembered” something of which he had little or no first-hand experience, partly because of his age and partly because of his location, geographically close but mentally far from socialist Hungary.

According to Piotr Piotrowski , who has reflected at length on the condition of the arts under socialism and post-socialism, the recent past is almost always traumatic in those countries whose legacy was life under socialism.(Piotr Piotrowski, “New Museums in East-Central Europe: Between Traumaphobia and Traumaphilia,” 1968–1989: Political Upheaval and Artistic Change, Claire Bishop and Marta Dziewanska, eds. ( Warsaw: Muzeum Sztuki Newoczensej, 2009).) Although there were no big shows commemorating the 20th anniversary of the fall of the wall in 2009, in Hungary, the remembrance of the not-so-remote past, the Kádár era, became the topic of two major exhibitions that took a new approach to the problem of memory. They dealt with this topic not just as an issue of the past but also as a reflection on the present with which the contemporary arts must grapple. Amerigo Tot: Parallel Constructions (curated by József Mélyi) and Other Voices, Other Rooms – Attempts at Reconstruction: 50 years of Balázs Béla Studio (curated by Lívia Páldi).

Amerigo Tot (1909-1983), a Hungarian artist who lived mostly in Italy, would have been 100 years old in 2009. The idea to make an exhibition of Amerigo Tot came from outside professional circles as a suggestion to the Ludwig Museum–Museum of Contemporary Art Budapest. Somewhat surprisingly, the idea was not summarily rejected with reference to the work’s uneven or middling quality, or to the relevance of the work of an artist who was “forgotten” after his death, or to the apparent lack of interest by art-historical professionals in his oeuvre. An exhibition organized on his would-be 100th birthday promised a celebratory kind of exhibition in the spirit of the 19th-century cult of the individual (male) artist.

Amerigo Tot (1909-1983), a Hungarian artist who lived mostly in Italy, would have been 100 years old in 2009. The idea to make an exhibition of Amerigo Tot came from outside professional circles as a suggestion to the Ludwig Museum–Museum of Contemporary Art Budapest. Somewhat surprisingly, the idea was not summarily rejected with reference to the work’s uneven or middling quality, or to the relevance of the work of an artist who was “forgotten” after his death, or to the apparent lack of interest by art-historical professionals in his oeuvre. An exhibition organized on his would-be 100th birthday promised a celebratory kind of exhibition in the spirit of the 19th-century cult of the individual (male) artist.

Amerigo Tot, or as he goes by his original name, Imre Tóth, was a simple peasant boy, the son of a policeman, who in the 1920s and 30s began to study art and participate in leftist demonstrations. In 1930 he was accepted at the Dessau Bauhaus where he studied for half a year. He was an adventurous man; he served as a sailor, went to Berlin, was arrested and taken to an internment camp, escaped from the prison (at the price of killing the guard with the help of a Polish poet) and fled to Italy, later joining the partisans. Here he worked as a sculptor and participated in different competitions for commissions. After the war he did not return to Hungary but kept good connections with the Hungarian cultural institute in Rome.

Georg Lukács wanted to convince him to return to Hungary, but instead Tot acted in films and had adventures: racing cars, pursuing lovers, and generally living a romantic existence. He received important commissions, the most famous among them being the façade relief of the Termini Railway station in Rome. As an artist, Tot was a versatile modernist sculptor, lacking a consistent style but with a broad interest. One can safely say that as a personality he was more exciting than as an artist. He was a very useful “actor” for the socialist cultural regime. When he was referred to Hungary he had gained the epithet of “world-famous.” For the late socialist regime, the Kádár era, or to use the categories that were worked out by the most important cultural director of the regime, György Aczél, the era of the three T’s (in Hungarian, this stands for T?r-Tilt-Támogat/ Permitted-Prohibited-Promoted),(For the English transcription of this expression I am grateful to Dániel Sipos, who translated an earlier version of the present essay: “The Kádár Era as Exhibition Concept: Amerigo Tot and the Balázs Béla Studio.” http://exindex.hu/index.php?l=en&page=3&id=731) he was an artist whose leftist sentiments and international recognition (which as recent research has shows was highly overestimated) made him an important celebrity.

Tot visited Hungary in 1968 for the first time after the war and eventually returned home in 1975. According to Miklós Haraszti, the preceding years 1973 and 1974 had been years of arrests and house searches when many dissidents were strongly “encouraged” to leave Hungary. The most important among them were the writer György Konrád (1973), the sociologist Iván Szelényi (1973) and the artist Tamás Szentjóby (1974). The Chapel in Balatonboglár, an alternative space for performances and dissident artists was closed by the authorities in 1973. On the other hand, as the newsreels reflect, Hungary was a good place for foreign (Western) tourists to come for vacation and leisure. In this context of a hardening political atmosphere, tourism and “world famous” Amerigo Tot’s return to his homeland proved that the regime did indeed have a human face: Hungary was a good place to come.

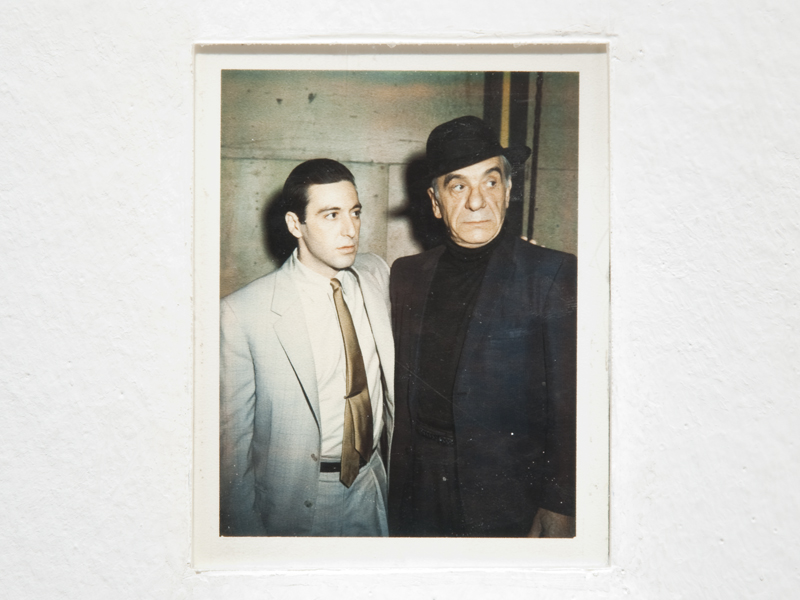

Amerigo Tot was almost instantly forgotten after his death. Cultural policy-whether under socialism or for the successor governments-requires a living spokesman. To become a national art monument the quality of Tot’s work was too mediocre and his acceptance of commissions for everything from public spaces to churches smacked of opportunism. His works were neither catalogued nor archived in museums. Truth be told, Hungarian art history has yet to produce many missing basic monographs and comprehensive studies of a number of significant artists, both in English and in Hungarian. These accumulated absences, missing researches and publications played an important part in the reception of the Tot exhibition, which was rather ambivalent. If Tot was a bit of a star once, it was as much for his life as his art: he appeared in films, knew Al Pacino and other celebrities, met the pope, and had the reputation as a lady’s man. And if he made sculptures for the sports arena or the train station in Rome too, well, all the better.

Amerigo Tot was almost instantly forgotten after his death. Cultural policy-whether under socialism or for the successor governments-requires a living spokesman. To become a national art monument the quality of Tot’s work was too mediocre and his acceptance of commissions for everything from public spaces to churches smacked of opportunism. His works were neither catalogued nor archived in museums. Truth be told, Hungarian art history has yet to produce many missing basic monographs and comprehensive studies of a number of significant artists, both in English and in Hungarian. These accumulated absences, missing researches and publications played an important part in the reception of the Tot exhibition, which was rather ambivalent. If Tot was a bit of a star once, it was as much for his life as his art: he appeared in films, knew Al Pacino and other celebrities, met the pope, and had the reputation as a lady’s man. And if he made sculptures for the sports arena or the train station in Rome too, well, all the better.

The Tot exhibition received much negative criticism, although some praised it (including myself). One of the strongest critical remarks about the exhibition related to the absence of painstaking research into Tot’s work.(Not long after the show’s closing, an Amerigo Tot monograph was published by Péter Nemes who actively participated in the preparations for the exhibition.) Allegedly the curator made Tot a target of criticism; some even said that the curator, by presenting an eclectic clutter of works along with documents of Tot’s adventurous, romantic life, made a mockery of the artist before people actually had a fair chance to be informed about and judge the true nature of the oeuvre itself, and that there was a lack of comprehensive research and knowledge of the work.

The show’s curator confronted Amerigo Tot in terms of two “constructions,” one centered on the myth of the legendary heroic male artist, the other on the world-famous communist who returns to his native land. It was a conceptual exhibition that instead of simply celebrating Tot reconstructed the complexity of the cold war in which he lived and worked. That is why the show became a target for everyone. Those who wanted to celebrate Tot objected to it because the exhibition did not give them a chance to do so. Those who expected criticism of the regime objected that it criticized an artist whose work has not yet been thoroughly researched. These objections revealed a characteristically divided relation to the past.

The exhibition raised the question as to how canons are formed today and in the past; it examined the view that the artist is autonomous and stands above politics; and it revealed how mutually dependent different ideological systems can be. The Tot show was like a stone thrown into a pond; it revealed the conflicting views of both traditional and progressive art historians, critics, and curators while at the same time making it clear how uncomfortable it can be to remember a past that was far from being heroic or impeccable. Through the exposure of this once instrumental but now forgotten oeuvre, the exhibition was able to throw light on a specific aspect of the Kádár era’s art policy, placing Amerigo Tot in this complex moral system of relations.

The second show I want to discuss is the one organized at M?csarnok to commmemorate the 50th anniversary of the Béla Balázs Film Stúdió. The studio has actually been closed and now has a huge archive. I would like to call it an archive of socialism: I would like to call it an archive of socialism: these films provide us an opportunity literally to look the recent past in the face. The films are hosted in M?csarnok/Kunsthalle, while their ownership and legal status are still somewhat unclear. Yet in a certain sense, their indefinite legal and artistic status was part of the “contemporary” status of the exhibition: on display was not just a document from the past, as in a historical museum, a museum of film history, for instance; rather, the exhibition was a kind of grand-scale socialist archive. At the same time it exposed the uncertainty of that archive, the ambivalence of the past for post-socialist artists and for contemporary art institutions alike.

While Amerigo Tot was a “promoted” artist, the Béla Balázs Stúdió had a different status in the system of the three Ts and its web of censorship and self-censorship in cultural production. The studio was financed by the state (!) and yet operated, asit was euphemistically worded, without any obligation to organize public screenings. It was “counterculture supported by the state,” or the “velvet prison,” as Péter György puts it, citing Miklós Haraszti’s phrase.(For Péter György’s opening speech, see http://www.mucsarnok.hu/new_site/index.php?lang=hu&t=515) This phenomenon was not really common in other socialist countries. This is also a feature characteristic of the Kádár era, the other face of the “humane” regime: acknowledging and incorporating opposition and subculture within specific confines, as an outlet for tension and anger.

The concept of curator Livia Páldi was to create a new “place of memory”—in the sense of Pierre Nora’s influential study—from the archival material. Hundreds of films were running in parallel, and to experience the exhibition fully the visitor had to return several times and conduct a sort of individual “archival research.” Most of the films screened in the show, if they were experimental films made by visual artists, were related to art in one way or another. Many of the visitors were former members of the 1970s and ’80s subcultures and they could easily encounter their younger selves in these films. The specter of nostalgia threatened everywhere. Priorities shifted considerably during the 50 years of BBS’s activity, and it was impossible to show all the films. Filmmakers objected that documentaries received less attention; this imbalance, however, was repaired by the accompanying film screening programs, which in their capacious selection featured numerous documentaries as well.

In the central space of the exhibition two films were running in parallel, thus juxtaposing counterculture and official cultural policy. One was a documentary about the history of a sculpture commissioned by the workers of a factory which was then taken away by the authorities “on aesthetic grounds” (Unveiling, by Györgyi Szalai and László Vitézy, 1979); the second was Miklós Erdély’s Version (1979), a reenactment of a blood libel touching upon the theme of anti-semitism, a taboo topic under socialism.

Internationally, many contemporary artists criticize curatorial practice by taking over curating and research themselves (in Hungary, the artist-duo Little Warsaw uses this approach to recontextualize the remnants of socialism). In the two shows I am discussing here, both curators, Mélyi and Páldi, were inspired by contemporary art practice rather than the norms of professional curatorship in Hungary.

In presenting a segment from the Kádár era, József Mélyi in his Amerigo Tot show examined and created context by means of the (intellectual) relocation of a “monument of socialism.” (In his catalogue text the curator explicitly mentions the analogous activity of Little Warsaw.) For her part, when Lívia Páldi explored the possibility of exhibiting a vast archive she was well aware that it would be impossible to show the entire material. Her sight sharpened by Little Warsaw’s Instauratio, she selected the film Unveiling as one of her show’s focal points.

In their own time the filmmakers whose work was featured in Paldi’s show violated the borders of the zone of tolerated freedom demarcated by the three T’s. In a paradoxical way they ended up playing a crucial role in the critique of the Communist regime. By mapping out sub-cultural networks, Paldi’s show reconstructed the genealogy of the mutual dependency of the official sphere, on the one hand, and subculture, on the other. The functioning and especially the afterlife of this subculture is a delicate subject due precisely to this mutual dependency, since it erodes the myth of heroic opposition.

Both shows I examine here stirred the waters and attracted attention as well as some resistance. This resistance might be a sign of traumaphobia, the fear of confronting the many different faces of the past. It may be uncomfortable to revisit the Kádár era but it is a big step that the remembering of our socialist past has now begun. Still, idle aesthetic arguments and prolonged discussions of things like autonomous art may not help us work through our historical legacy.