Archives Don’t Burn: Hito Steyerl’s Film “Journal No.1 – An Artist’s Impression” (Film Review)

Journal No. 1 – An Artist’s Impression. Directed by Hito Steyerl. 2007. Video: 21 min.

Journal No. 1 – An Artist’s Impression. Directed by Hito Steyerl. 2007. Video: 21 min.

“Once upon a time there was a country…” This sentence, borrowed from Dušan Kova?evi?’s novel of the same title and later adopted into Emir Kusturica’s film Underground, evokes a temporality that is tied to origins and to the kind of arkhè Jacques Derrida challenged as part of his undoing of the metaphysical relationship between being and its history in Western culture and thought. Steyerl’s short documentary questions the fairy tale perspective on Yugoslavia’s mythical origins and its relationship with time. The film tells of a very real moment at the beginning of the Yugoslav dream of brotherhood and unity. In fact, it is more a sisterhood on which Steyerl chose to cast her cinematic gaze. Her film focuses on the socialist program of advancing women’s rights within the context of the deeply entrenched patriarchal values of traditional Balkan culture. More specifically, it addresses the opportunities the new Yugoslav society offered to Bosnian, mainly Moslem, women to participate in the common dream of universal literacy and secular education. However, such dreams tend to be followed by rude awakenings, often caused by the violence that gradually turns them into nightmares.

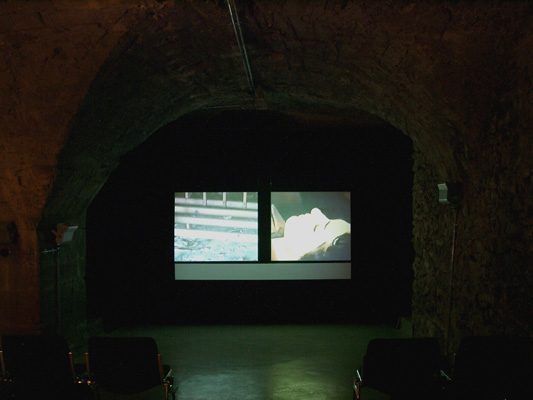

On one level, Journal No. 1 is about the role of film as historical testimony. More specifically, it addresses the way in which film as a medium was instrumental in constructing one of the founding myths of Yugoslavia, involving the campaign for the literacy and enlightenment of its rural population. However, the burning of the archives of the Sutjeska film studios during the last Bosnian war (1992-1995) – Steyerl’s focal point – erased all visual documentation of the literacy campaign in rural Bosnia in 1947. Steyerl’s short film about the absent visual testimony of Bosnia’s past deals with forgetting as an effect of violence and contingency. Steyerl’s is not a cinematic search for an origin with a capital “O” but a step-by-step visualization of a collision of several universes of meaning tied to the past and present of Bosnia and Yugoslavia. The director’s cinematic poetics does not slip into nostalgia for the homeland, nor does it yield to facile, media-generated formulas about Bosnia as a place of exemplary horror and suffering. Instead it visualizes the past through a gaze that addresses the possibility of remembering as a communal act and the process of forgetting as a result of war and its violent annihilation of cultural memory.

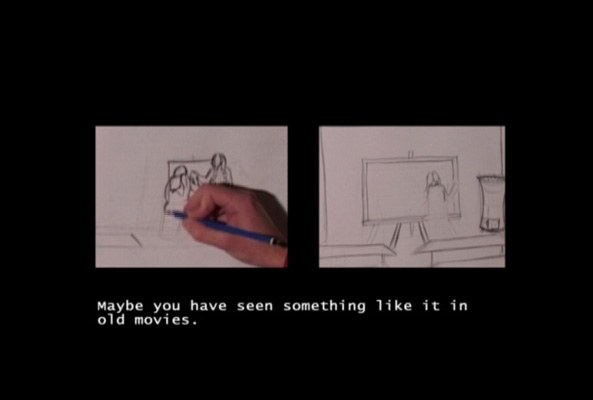

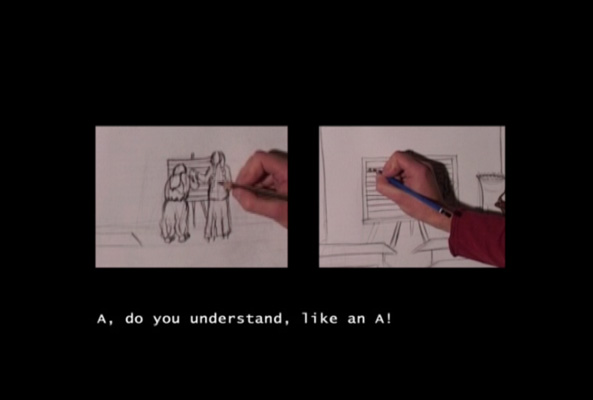

The film develops its narrative on several semantic planes, using a double screen to juxtapose various possible meanings of the memories created, imagined and erased by the war and the ensuing communal violence. The (vanished) Film Journal No. 1 – the official story of Bosnia’s literacy campaign – is the missing link in Bosnia’s post-WWII memory. What is perhaps even more important is Steyerl’s documentation of the widespread popular support for Tito whose official portraits in the classrooms overlook the Moslem women as they take off their veils. This scene is spliced into Steyerl’s film from a different piece of documentary footageentitled Film Journal No. 4. It tells the story of the survival of at least portions of the Southern Slavs’ collective memory. The sheer exhilaration radiating from the Muslim women’s faces in these scenes testifies to an age of optimism and change that may serve as inspiration for the generations to come. Steyerl’s film could be called an “artomentary” since it collages various layers of visual imaginary, borrowing from Bosnian feature films like Sje?aš li se Doli Bel (1981) or Valter brani Sarajevo (1972) and from various types of documentary footage. The director’s technical procedures are art-based yet they bring the viewer closer to acknowledging the complexity of history than any mainstream documentary about the Bosnian war and the end of Yugoslavia. Steyerl achieves this effect by creating a palimpsest of visual inscriptions, layered to develop a complex narrative structure and to help reveal the complicated truth underlying the formation of collective memory and its destruction.

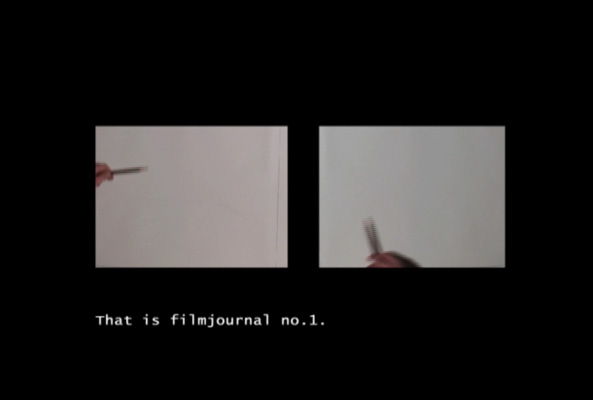

The most striking part of this process is the creative engagement of Armin, a graphic artist whose process of drawing opens the film. Armin’s hand and the pencil are captured as he attempts to visually transform and recreate the missing footage while listening to a woman’s voice telling the story of the literacy campaign that was the subject of the now-missing film. This testimony, told in the wonderfully warm and soft voice of a Bosnian woman, is perhaps the most memorable part of the film. It strikes the viewer as an oral testimony to a moment that has lost its filmic existence during the burning of the archive. The combination of the verbal and the visual, standing in as a substitute for the missing footage, calls on memory to substitute for the medium of highest technical reproducibility (film) that has been lost in the war. These attempts to struggle against forgetting may seem futile in the beginning. However, if you watch the film a second and a third time, they begin to function as successful mementos of the Bosnians’ struggle to preserve their culture in the face of overwhelming odds. The reversal of the techno-mimetic process whereby drawing and voice are three times removed from the original event poses crucial questions about memory and its representation, especially with regard to those areas of the world that are subjected to war and violence.

The final scenes of Steyerl’s film are devoted to Armin’s story. He recounts his experience of being caught in someone else’s violent nationalist dream. These scenes also offer an effective transition from the more philosophical considerations of memory to the artist’s personal reflection on her own sense of loss and displacement in the wake of the ethno-territorial reshuffling carried out by the new nationalist leaders. Steyerl’s film could be an effective teaching tool in classes related to the former Yugoslavia and, more generally, to the problem of memory and its loss in areas affected by political conflict.