Some Notes on Transnational Art History in Practice: Revolutionary Romances? Global Art Histories in the GDR at the Albertinum

Revolutionary Romances? Global Art Histories in the GDR at Albertinum, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, November 4, 2023–June 2, 2024

A decolonial discourse that has materialized in exhibition practices in recent years has set us on a course of unlearning and exploring potentially lesser-known histories. The exhibition Revolutionary Romances? Global Art Histories in the GDR at the Albertinum in Dresden (November 4, 2023–June 2, 2024) shows that we still have much to learn about the histories and forgotten cultural heritage of the Cold War. With two hundred historical art objects, most of them from the Dresden State Art Collections (Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, SKD), several contemporary art projects, a series of oral history video interviews with actors involved in cultural diplomacy in the German Democratic Republic (GDR),(The exhibition was realized in collaboration with TU Dresden’s project Art in Networks. The GDR and its Global Relations. All interviewers are available on line at : https://artinnetworks.webspace.tu-dresden.de/de/videos) and extensive curatorial texts accompanied by a glossary, this historical exhibition challenges both the art of socialist internationalism and the culture of post-migration Germany.(Contemporary Germany has been defined as a post-migration society – i.e. a country of immigration – understood “not only empirically but also narratively.” See: Naika Foroutan, “Post-Migrant Society” (April 21, 2015), Federal Agency for Civic Education (Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung/bpb) https://www.bpb.de/themen/migration-integration/kurzdossiers/205295/post-migrant-society/) The term “post-migration society,” used in the German public debate, describes a current social order in the country that has been shaped by the experience of migration. The exhibition presents the diversity of transnational cultural relations in the GDR beyond the binary of West and East, and its politics of alliance with socialist countries around the world as potential genealogy of contemporary post-migration identity. With a genealogy that differs from the current neoliberal globalism and which comes from the marginalized former East of the country, the exhibition is an important proposition for the internal German debate in which the East is usually blamed for the rise of right-wing populism and anti-immigrant movements.

Revolutionary Romances? Global Art Histories in the GDR, Albertinum, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden. Foto: Oliver Killig

The critical dimension of the exhibition can be summarized as a history written in the present about the shared past for a more pluralistic society/nation in the future. Instead of thinking about a general “better future,” however, the exhibition narrows down to the question of what a museum for such a pluralistic society should look like and, in particular, a museum of post-migration Germany. What should it collect? Whose stories should the museum tell? What responsibility does it have in creating empathic and respectful interactions between people? Post-migration does not indicate here the end of the migration process, but suggests a focus on the social negotiations that take place in the country after migration phase. These questions are therefore relevant to this entire process, and the exhibition’s most compelling moment comes precisely from their intense exploration.

Revolutionary Romances? Global Art Histories in the GDR, Albertinum, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden. Foto: Oliver Killig

As such, the curators are not just interested in rewriting transnational histories of socialist art, but it can be argued that their project is grounded in the tradition of socialist museology, whose main goal was not to “spread objective, detached knowledge, but to link the content of individual exhibitions with the current uses of social, cultural and political life instead.”(Agata Pietrasik and Piotr Słodkowski, “Promoting Culture in Polish People’s Republic in the 1950s – at the Meeting Point of Practice and Ideology. The Case of Travelling Exhibitions,” in Jérôme Bazin and Joanna Kordjak eds., Cold Revolution. Central and Eastern European Societies in Times of Socialist Realism, 1948–1959 (Milan: Mousse Publishing, 2021), pp. 100–105, here p. 102.) Rather than following the bourgeois tradition of autonomous art, socialist museology was concerned with responding to social and political issues. Likewise, Revolutionary Romances? addresses contemporary issues of migration, mobility, war, and the function of politically engaged art through the prism of historical concepts of international socialism and social realism.

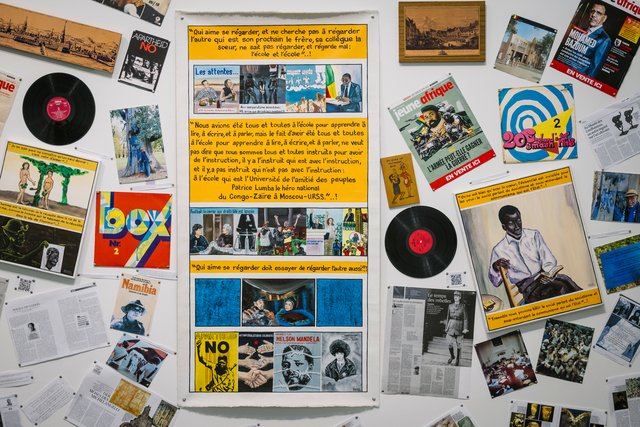

Georges Adéagbo, Les étudiants Africains et le Socialisme, 2023. Albertinum, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden. Foto: Oliver Killig.

Situated in the large open space of the Albertinum, the exhibition explores the obliterated field of relations between GDR and global socialism in five chapters: Ideas and Icons, Art and Solidarity, Travel and Contact, Temporary Guests?, and Collected Fraternity. It uses the modest aesthetics of a historical exhibition, drawing attention to details, individual works, and thematic frameworks rather than overwhelming the viewer with visuality. It features works by artists from the Global South collected by SKD as a result of international exchanges, and works by mainstream artists from the GDR who were able to travel to other socialist countries such as Lea Grundig or Doris Kahne. These works are accompanied by contemporary projects that deal with the issue of diaspora and migrant communities in socialist and today’s Germany, in formats such as animated film (Arlette Quỳnh-Anh Trần, PLATTENLOTUS, 2022), installations with archival documents and images (Georges Adeagbo, African Students and Socialism, 2023), or series of documentary black and white photographs (Matthias Rietschel, Vietnamese in Dresden, 1987–90). The exhibition also includes works by art students from the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts (from Brazil, Burma, Cambodia, Chile, China, Colombia, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Iraq, Lebanon, Libya, Mongolia, Mozambique, Palestine, Syria, and Vietnam) who have studied in the GDR as part of student exchange programs.(It is difficult to see this exhibition without comparing it with the recent Leipzig exhibition Re-Connected. Art and Conflict in the Brotherland, which focused on the artistic production of foreign students from academies in Leipzig, Dresden, East Berlin, or Halle. The Leipzig exhibition was divided into separated sections of art created under socialism, juxtaposed with new commissions, and concluded with a research section.)

Revolutionary Romances? opens with a watercolour series by Dresden-based communist artist Lea Grundig (The Communist Manifesto series of 1968) whose titles alone could be interpreted as socialist propaganda, but whose content and formal complexity – along withthe author’s integrity as a committed communist – would make such an interpretation extremely reductive. The exhibition offers a wide range of representations of the official GDR policy of international solidarity, and calls attention to the stylistic and media richness of realistic art. It includes formally modest, black and white images of global community and solidarity, such as a figurative engraving by Dieter Wuttke Solidarity – now more than ever (1973) and a drawing by Ronald Paris, International Solidarity (1975); and intensive psychedelic images of socialist heroes by Raul Martinez (Posters of Che and Fidel from the late 1960s). A large part of the second section consist of compassionate realistic images of victims of military conflicts in Vietnam (including Heizn Lohmar’s painting Vietnam is Suffering, 1967; Walter Arnold’s wooden sculpture Forward and Never Forget – Solidarity, 1967; and a photomontage by Joachim Jansog entitled February 17, 79, 1979), Cuba (Carmelo Gonzales’ dramatic series of woodcuts entitled Island of Freedom, 1963), Chile (Hartwig Ebersbach’s series of large oil portraits entitled Dedication to Chile, 1974, which were based on police photographs taken in 1871 depicting twelve victims of Paris Commune), or the Congo (Janos Pandl-Kiss, Patrice Lumumba, stucco bust, 1961/2). These works do not lose their significance when viewed today in the context of current wars and armed conflicts. On the contrary, they affect us as contemporary statements.

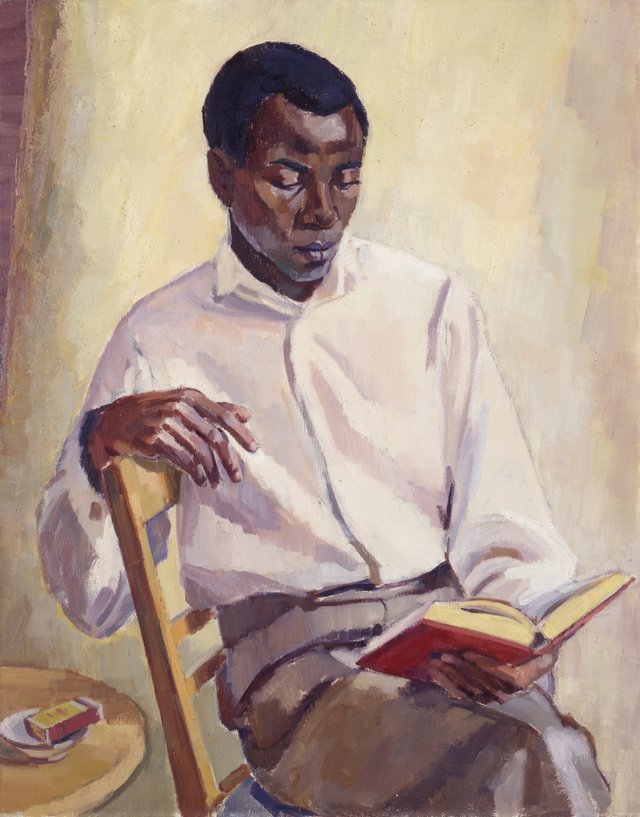

Eva Schulze-Knabe, Chukwuemeka Ogbue (Student aus Nigeria), 1960. Albertinum, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden.

The exhibition showcases historical art produced within the framework of the GDR’s policy of alliance with global socialism and participation in decolonial struggles, often from a strategic perspective. East Germany’s foreign policy cannot be seen in isolation from its internal political system of oppression. We cannot treat this policy uncritically as a liberating force, but rather as a part of the Cold War rivalry that included the instrumentalization of decolonial struggles. At the same time, the actors involved in the creation of this transnational culture – artists, organizers, students – were not just passive objects of a policy from above, but were active in negotiating their stakes and strategies and, as the exhibition shows, some reflected a patronizing attitude toward struggles in the “Third World.” An example of the latter is a series of woodcuts by Ani Teufel that depict Indonesian, African, Chinese, and Vietnamese women in infantile and stereotypical ways. It is also undeniable that the GDR, like other Eastern Bloc countries, used artistic production for anti-imperialist and anti-Western propaganda. Given the diversity of the artistic material on display, this international cultural production cannot be simply reduced to evidence of the instrumentalization of art by the socialist state. If socialist artists embraced slogans of socialist solidarity, contemporary artists play the role of “inspectors” form the future. Hamlet Lavastida’s work Cultural Profilactica (2020-21), which deals with the conditions of political repression and the impossibility of dissent in Cuba, shows what can be hidden behind slogans of peace. This large installation of paper cuttings is based on photographs, empty symbols and meaningless slogans of political and public organizations that have controlled and restricted the public sphere since the revolution in Cuba. Some works from the socialist era also fulfil this task, such as photographs by Jürgen Nagel, which show enthusiastic slogans of socialist propaganda on deserted or empty public buildings, schools, and factories. The contrast between these slogans and the reality against which they are set provides a critique of the system that superficially embraces ideas of freedom and equality, but in fact offers a grim reality.

It is worth placing Revolutionary Romances? in the context of current trends in regional art history and specifically in connection with the shift from the totalitarian paradigm to interests in everyday culture, history “from below” and the broader reconstruction of socialism based on lived experience. This includes concentrating on the individual and collective agency of the people who lived and created culture at the time, and presenting them as active actors and negotiators of socialist culture rather than passive recipients of cultural policy measures. Revolutionary Romances? incorporates this perspective. It obviously represents “the system” by showing official iconography of anti-imperialism and official art infrastructures, such as student exchange programs at the Dresden Fine Arts Academy and the Center for Art Exhibitions of the GDR, which was a government agency responsible for internationalizing art and organizing exhibition. It does not present the archives or programs of these institutions, but rather the voices of the participants in these networks, who speak about their experiences either through artistic means (artworks) or directly in video interviews (Arts in Networks project). For example, the exhibition includes interviews with exhibition organizers from the Center for Art Exhibitions of the GDR (Zentrum für Kunstausstellungen der DDR), who talk about their work on GDR exhibitions abroad. Revolutionary Romances? avoids making judgments about people involved in socialist culture, but instead asks questions relevant to contemporary culture: Who can travel freely? Which conflicts are invisible? What is the role of art in society? It shows that there were limits to these freedoms in the GDR and – by including contemporary art projects that deal with invisibility of migrant communities – points to the current exclusions and marginalizations in German society.

The exhibition is part of a research project by SKD that revolves around the question of the transnational cultural history of East Germany, and has to date consisted of two academic conferences as well as a prologue exhibition based on the holdings of the SKD print department.(See conferences organized in 2022 by Albertinum, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, and TU Dresden, Germany: The Global GDR – Transcultural History of Art (1949–1990); Kunst im Austausch: Kontakte zwischen der ehemaligen DDR und Lateinamerika (Chile, Kuba, Brasilien); and Revolutionary Romances: Into the Cold – Alternative Artistic Trajectories into (Post-) Communist Europe.) Rewriting the GDR’s cultural history and rethinking its relevance for today’s Germany necessitates a reassessment of the art created under socialism – a task that SKD and many other museums “in the East” have faced since 1989. This reassessment takes place in the current exhibition through an international contextualization of historical works and their actualization.

The exhibition offers a complex view of history, employing a synchronic rather than linear narrative that reveals the contemporaneity of the issues raised by socialist artists. This happen through formally fitting juxtapositions of works, but it is also realized through spatial arrangement and discursive devices such as curatorial texts and questions placed on the walls around the works. A spatial arrangement intensifies synchronicity by emphasizing the connections between past and current projects and concerns. Some juxtapositions are so strong that they almost collapse into installations, as in the case of the portraits by Rudol Bergander (Therese from Togo, 1963) and Alfred Hesse (Franciscus Effendi, Student form Djakarta, 1971), which are juxtaposed with a two channel video installations by Dana Lorenz, Re-writing Gaze (2018) within a section that raises the question about the gaze in the museum. In this curatorial constellation, the paintings take on a new level of meaning. From portraits of intellectuals from minority backgrounds, they become images of the sitters’ returning gaze, thematising asymmetries in looking and being looked at.

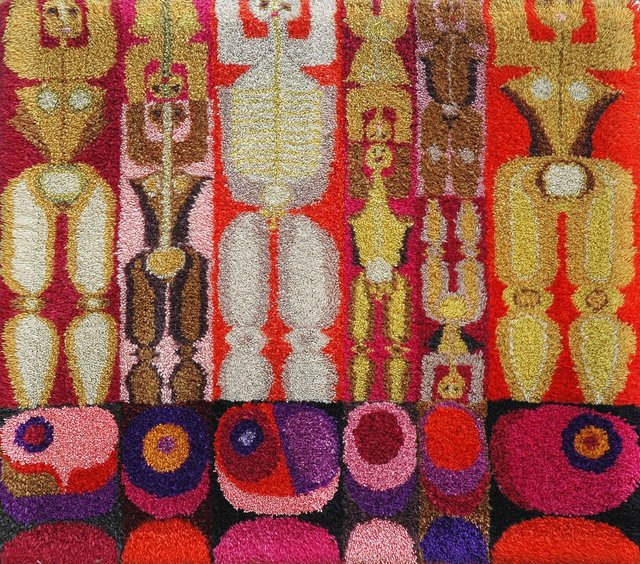

Margarita Pellegrin, Demonstration, 1975. Courtesy of the León Pellegrin family.

Rethinking socialist realism as an international, flexible and multifaceted form of expression is another approach to re-evaluating the art made under socialism . The exhibition shows the diversity of socialist art and its commitment to realism in many forms and media, ranging from folkloric objects such as a wooden hanging chandelier with carved and painted figures forming a circle (Martin Angermann, The Friendship of the Youth of all Peace-Loving Peoples Ensures Peace for the World, 1951) or colorful wool tapestries depicting anti-Pinochet political protest in Chile (Margarita Pellegrini, Demonstration, 1975). Following the socialist program of non-autonomous art that does not prioritize the classical media of painting and sculpture, the exhibition includes variety of means such as posters, watercolors, engravings and drawings. It also presents many large and expressive oil paintings depicting victims of political conflicts or realistic sculptures of historical figures important in the decolonization process or anonymous victims of colonial wars. However, it presents these works as part of anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist creativity rather than as autonomous art objects. The works by contemporary artists with very different aesthetics can easily be included in this artistic genealogy, as they are in line with the socialist vision of artistic-political engagement. In all cases it is an affective art, ontologically committed to realism, that is on the side of the oppressed; art that shows us the consequences and injustices of global imperialism – then and now. This is the most problematic aspect of the exhibition – a certain flattening of the context by presenting socialist propaganda and socialist modernism as a genealogy of contemporary engaged art. At the same time, it is a proposition that raises the critical question of the instrumentalization of art in general. Another potentially problematic aspect of the exhibition is that the curators accompany the viewer very closely, almost as though they do not trust the art itself or the ability of the viewer to engage with it. They pose questions on walls, and direct our reading, using the art from the past to make a point for today. Does this strategy benefit the art presented? Defenders of art’s autonomy might find this direct attempt to revive its relevance within the rigid framework of an exhibition narrative reductive.

Instead of the sort of affirmative aesthetic that can be found in many decolonial exhibitions, Revolutionary Romances? tells a story of the official international cultural policy of the GDR.(For a discussion on affirmative aspect of decolonial debate see for instance: Joshua I. Cohen, Foad Torshizi, Vazira Zamindar, “Art History, Postcolonialism, and the Global Turn”, ARTMargins 12, no. 2 (2023): pp. 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1162/artm_e_00346.) After decades of amnesia, this society is revisited with a series of new questions (reflected in exhibition chapters) that go beyond the ideas of the artist as conformist and the artist as dissident. Instead they reveal a rather broad spectrum of artistic affection for socialist ideas of international solidarity. Ultimately, however, the exhibition questions the limits of “national containers” such as national art history, heritage, and identity, which ignore or erase the pervasive cross-border circulation of objects, peoples, ideas, and works. It does so through the representation of the transnationality of artistic production that underscores the necessity of the museum’s commitment to internationalization. It is worth remembering, that internationalism, in the Marxist understanding, was a necessary prerequisite for the development of culture in general. One could also say that it was precisely this aspect that enabled the Dresden museum to reclaim the art of the socialist past for the present. This artistic production could not simply be presented as an instrument of a compromised state cultural policy. Its very transnationality made it possible to examine the intertwined histories of the individual artworks and to show how they relate to each other and to contemporary practices.

The exhibition Revolutionary Romances? offers a transnational art history in practice. It shows, a transnational phenomenon of socialist realist art understood not as a particular style or set of motifs, but rather as a diverse and historically evolving artistic practice that represents and supports the global socialist project. It redefines it as a bridge between revolutionary, proletarian art of the early 20th century and contemporary artistic activism – as a genealogy of contemporary politically engaged art by emphasizing the continuity of themes and approaches.