Socialist Evening Realistic Post

I.

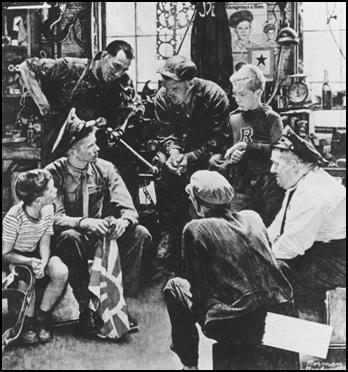

It does not take an experienced connoisseur to notice the uncanny similarity between the widely popular art of Norman Rockwell and certain artworks of Socialist realism.

Similarly, some of the official art created in the Soviet Union during Rockwell’s most successful years could easily pass as emblematic of the Saturday Evening Post covers depicting that era.

This can be a confusing realization given that these images originated from the two very polarized ideological standpoints of that time. Is this a mere coincidence of style, or are these two forms of expression somehow more deeply bound?

The art of the previous century is now seen as being a larger and a much more complex phenomenon than just the avant-garde and its subsequent developments.

Norman Rockwell has recently been admitted into the art Pantheon of the 20th century in the United States and the western art world. We now suddenly see him as a serious and significant artist. Socialist Realism isfar from undergoing a similar revision, both in the former Soviet Union and in the rest of the world.

Works by artists of Socialist Realism are mostly seen as evidence of Stalinist political terror or, in the best cases, as tickling examples of Soviet camp. The passing years seem to have brought out the best in Rockwell, starting with his surprisingly progressive politics and ending with his unusual formal qualities, but in Socialist Realism, time has unmasked the worst.

After Soviet modernism from the heroic 1920s, the level of hypocrisy, propaganda, and falsehood in most of the examples of Socialist Realism appear to be unacceptable, almost repulsive, and certainly not vanishing with time. It can be so overwhelming that it is difficult to see these works as art.

No matter how hideous we may find its style, Socialist Realism is not only an illustration of the political history of the period, but a mostly unrecognized element of modern art.

Besides the countless portraits of Stalin and other Soviet leaders and the obvious political propaganda, Soviet painters also produced hundreds of paintings depicting the lives of common people, the so-called “genre of everyday life.”(In Russian the term for the genre of everyday life is bytovoi zhanr.)

The common people are, of course, highly idealized, but ideology here seems to have been pushed aside, if not replaced, by intimate and universally acceptable themes depicting the peaceful domestic life, themes bearing that curiously strong and puzzling resemblance to Norman Rockwell’s images.

Let us look at the painting Low Marks Again by Fedor P. Reshetnikov. It shows a sad schoolboy who has just confessed with reluctance his school failures to his mother and two siblings. His mom’s face is a mixture of worry and sympathy, as if she is contemplating her beloved son’s endangered future.

The harder-studying older sister in a freshly ironed pioneer uniform looks infuriated, while the pre-school younger brother maliciously enjoys his brother’s tough moment.

Only the dog, unaware of the gravity of the situation, happily greets the poor boy, possibly out of the unlikely prospect of procuring an afternoon of fun and games. Has the boy recently spent his time playing with the dog instead of doing his homework?

You could easily imagine this particular painting, if we alter a few details in the clothing and interior design, as an illustration from an American magazine. On the other hand, it is hard to see a fundamental difference between Rockwell’s A Portrait of the Miner and numerous Socialist Realistic versions dealing with the same subject.

We can even imagine Rockwell’s Freedom of Speech – with the important addition of a picture of Stalin hanging on the back wall – being the hit of any official Soviet exhibition from the early fifties.

If Rockwell’s images often come close to being caricature, it could be said that Socialist Realist paintings have a touch of the old masters and academia about them. Yet, both show the same sophisticated compositions and elegant,sleek execution.

Socialist Realism and the art of Norman Rockwell were often seen as the perfect antidote to the avant-garde, despite the fact that some authors argue the opposite.(See Boris Groys, The Total Art of Stalinism: Avant-garde, Aesthetic Dictatorship, and Beyond (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992).)

Socialist Realism turns radically away from the modernist notion of avant-garde individualism. Its culture is created collectively. It is not only the painter who creates the painting, for the politician who devises sets of rules, the ideologist who passes them on into society, the censor who makes sure the rules are being followed – all these people participate in its creation as well.

Teamwork is the method used because art under socialism can be planned and executed without the need for genius.

State controlled art unions distribute art to the people, send them to exhibitions, and supply them with inexpensive reproductions. Some of the paintings, like Lenin’s portraits by Brodsky, were from the beginning intended as models for mechanical reproduction.

Norman Rockwell worked alone, but he was part of an army of magazine artists and illustrators fulfilling their commissions and struggling to survive. They knew very well what their bosses and audiences wanted. If they failed, someone else could always immediately take over.

Magazines have to make profit; it is necessary to please everyone. Only a few can achieve star status, but once they do, they can, like Rockwell, receive commissions from the U.S. government.

Aside from the scrupulously realistic style and production techniques, Socialist Realism and Norman Rockwell’s paintings also share a strong emphasis on illustrative storytelling. They capture little things that are in the end highly symbolic, small parts of the world in which everything else reflects.

Their rich narrative scenes look like precise, but artificial, theater dramatizations of real life. Most of them show highly charged moments in which people are absorbed in their actions or the actions of other characters.

Typically, there are no real conflicts, but rather the peaceful and controlled orchestration of conflicts. There are no real tragedies in the world of Norman Rockwell or Socialist Realism.

There is no trouble that cannot be solved; every misfortune works more as a reminder that the whole system is running just fine.

We see the happy life of labor and recreation, a pre-planned world in which everyone knows how the tale is going to end, as if everyone is living an eternal childhood within a never changing golden air of happiness, and where someone else, some higher power, is actually in charge.

And indeed we do see a lot of pictures of children, children that misbehave or face difficulty, but from the adult’s point of view, they are just playing sweet and innocent games, very remote from the real evils of the everyday.

It is as if in the middle of the 20th century the world’s superpowers suddenly realized that they still needed the history of painting in order to clarify their views, to clearly communicate the ideals they were aiming for.

All of a sudden there was means to distribute these images to every family, making them virtually unavoidable. A similarly reproducible photograph would simply be too real for this job: a potentially dangerous record of what really happened.

Despite the fact that the paintings were executed using detailed photo-realistic technique and famous photographs were often used as sources, they look nothing like photographs.

Official Soviet photographs themselves are so heavily retouched that they remind one of paintings rather than photos. State propaganda does not need documents; in fact, it seeks to transform everything with a unique character into a standardized, idealized form.

The goal is not only to remove the smallpox scars from Stalin’s face or to eliminate Trotsky and other rejected commissars from a tribune. Socialist Realism, and in many cases Norman Rockwell as well, aims for something much higher: to givereality clear meaning, to replace reality with lucid allegory.

II.

In much simpler and traditional terms, the uniting principle of the art of Norman Rockwell and Socialist realism is kitsch.

We would not be the first to make such an observation. Clement Greenberg, in his essay “The Avant-garde and Kitsch”(See Clement Greenberg, The Collected Essays and Criticism, Volume 1, ed. John O‚Brian (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1986), 5-22.) from 1939, described relations between high art and kitsch, and for the first time outlined his theory of avant-garde art.

The original impulse to write his essay was much simpler: to reason out why avant-garde art of the Soviet Union was replaced by state distributed kitsch.

It was obviously puzzling to see Soviet art, after a revolutionary decade of abstraction and constructivism, going back to a mixture of 19th century realism and academic classicism with a dash of simplistic political propaganda.

Greenberg was right to be skeptical of asserting that this surprising turn was only the result of the political and administrative pressure Stalinism put on art. His reasoning goes deeper into the logic of the development of modern art and its interrelation with the audience.

To make his point, Greenberg used both Rockwell proto-Socialist Realistic painting as his examples of kitsch. It is interesting to see how valid these arguments are today.

Writer Dave Hickey, one of the foremost contemporary advocates of Norman Rockwell, explains that the power and popularity of Rockwell’s art comes from the fact that his paintings carry (or more precisely carried) no institutional guarantee of catching our attention.

In order to be seen and admired, viewers have to actively select them over thousands of other images in magazines or on billboards or packaging.

Greenberg describes in great detail a very similar selection process in “Avant-garde and Kitsch.” He reconstructs a hypothetical dilemma that a Russian peasant faces while standing in front of a painting by Picasso and another by the Russian academic painter Repin.

The stereotypical peasant, reduced here to being not much more than a donkey between two carrots, has to choose which art he likes better.

In the Picasso he sees the play of lines, colors, and shapes, in the other, a dramatic battle scene. Although he is able to appreciate some of the formal qualities of Picasso, he would always be charmed by Repin.

According to Greenberg, the peasant will always choose Repin because in his paintings there is no need to accept any difficult pictorial conventions.

Greenberg says of Repin, and would most likely say of Rockwell as well, that his art “tells a story” that can be effortlessly enjoyed. This makes him irresistible to the undereducated and exploited mass audience.

Russian peasants in the Soviet Union are lucky not to have been exposed to Norman Rockwell, whose art Greenberg considered even more captivating and corrupting than Repin’s.

He was probably not aware that Russian peasants already had similar masters of their own who were more than capable of competing with Rockwell. Artists like F. P. Reshetnikov, A. I. Laktionov, A.S. Gugel and R. V. Kurdevich only bear out Greenberg’s statement that kitsch is the first truly universal culture humankind has created.

It is interesting to realize that Soviet aestheticians in the era of Socialist Realism did not recognize the concept of kitsch; there is no place for kitsch in a socialist society.

The most important value of socialist art is its success in the promotion of communism to the masses. Bourgeois kitsch is empty, or it carries only a little bit of unremarkable content. Socialist Realism is overloaded with meaning; it is a vessel of propaganda whose goal was nothing less than to alter the whole of society.

Dave Hickey believes that to survive and to win the attention of the audience, Rockwell’s paintings have to speak in the language of acceptance and forgiveness.

Greenberg considers sympathy and magic to be the key values for successful kitsch painting. It almost seems as if Greenberg hates Rockwell for the same reasons Hickey loves him.

Things have changed indeed. More than sixty years after “Avant-garde and Kitsch,” Norman Rockwell – once an exemplary kitsch painter – is experiencing a great comeback.

A large retrospective exhibition of his works is currently travelling the United States on a triumphant three-year tour concluding at the Guggenheim Museum.

A retrospective of the once neglected Maxfield Parrish took place at the Brooklyn Museum in the summer of 2000, just a few months after a controversial show of rebellious young British artists called Sensation.

An interesting question is why Parrish and Rockwell have been rehabilitated at this particular point in history.

First, museums mount art exhibitions that “effortlessly tell their story in the understandable hope of attracting larger audiences.

But, part of the answer can also be found in the fact that, in recent decades, the once sharp distinction between kitsch and so-called high art has become much more complicated and blurry – maybe even non-existent.

These days no feelings of guilt are connected to kitsch; it cannot even shock anymore. In the past few decades kitsch, or whatever we call it, has been one of the most common and inspiring artistic strategies for contemporary artists, the most notorious probably being the much-respected Jeff Koons.

The remarkable thing about Koons is that he does not comment on or disapprove of our cultural values, he simply uses images he finds beautiful and appealing.

He does not criticize kitsch, but he does criticize high art for not being as powerful as kitsch can be. In fact, contemporary intellectuals standing between a late 1930s Picasso and a Saturday Evening Post cover from the same period may have plenty of scholarly ammunition to explain why they find Rockwell’s picture to be the better of the two.

III.

In the shadow of the Rockwell retrospective, it would be difficult to imagine a similar exhibition of Socialist Realist paintings fully concentrating on the artistic values of the works rather than on their political program or historical context.

Socialist Realism does not sell as well as Rockwell; in fact, from today’s point of view it is as far as you can imagine from the pleasure of effortlessly viewing Rockwell.

There are challenging questions that this multi-layered art immediately posts: How is it possible that art is able to soak up so much falsehood and still be so convincing and sincere?

Why did the avant-garde give up so easily? Is the avant-garde needed in our lives at all? These are not easy questions to answer; in fact, they are capable of affecting our perception of the whole of twentieth-century art.

Attempts at redefining or even taking on Socialist Realism from a scholarly perspective are rare and for the most part originate from outside the countries of the former Soviet bloc.

The most comprehensive study to date – an impressive volume of Socialist Realist Painting by the Englishman M.C. Bown(Matthew Cullerne Bown, Socialist Realist Painting (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 1998).) – not only does a great job at presenting long forgotten paintings, but its author also clearly demonstrates that Socialist Realism was not simply something political leaders ordered artists to do.

Socialist Realism had its own tradition and artists, and theoreticians struggled to clarify and develop their often surprisingly sophisticated views on art.

What M. C. Bown wrote about Socialist Realism applies for both the Soviets and for Rockwell: “The political message [of art] is reinforced by the romantic one.”(Ibid. 300.) But the key question remains: How much and to which extent has this romanticism managed to displace this ideology?

Unsurprisingly, most of the artists that grew up in the Soviet Union in the 1950s remember only the romantic side of the art that surrounded them.

In their accounts of their youth, Ilya Kabakov, Komar, and Melamid clearly remember the impact that these images had on them, realizing their ideological content only years later.

Poet Joseph Brodsky left a wonderful description of the effect one of these paintings had on him:

It is worth noting that in the puritanical atmosphere of Stalin’s Russia one could get turned on by the one hundred percent innocent Socialist Realist painting called Admission to the Komsomol, which was widely reproduced and which decorated almost every classroom. Among the characters depicted in this painting was a young blond woman sitting on a chair with her legs crossed in such a way that two or three inches of her thigh were visible. It wasn’t so much that bit of her thigh as its contrast to the dark brown dress she wore that drove me crazy and pursued me in my dreams.(Ibid. 255-256.)

IV.

Paradoxically and painfully, Socialist Realism with its doctrines and tutoring was taking part in an attempt to create a new society with a new set of values, no matter how mistaken those values may have turned out to be.

Artists, theorists, and viewers of Socialist Realism believed that art should play a role in society, but this society happened to have been under the control of one of the most evil dictatorships in history.

The formal style of Socialist Realism may have descended from its predecessors in the nineteenth century, but another important element in the evolution of its formulas is the fact that kitsch is the only truly classless art available.

Kitsch was embraced as the perfect artistic expression for the self-proclaimed state of the people. Art existed not just to be beautiful or smart, but to speak for everyone, to be on the chosen side in a dilemma between two paintings, to change people’s minds.

David Hickey writes:

Norman Rockwell invented Democratic History Painting – an artistic practice based on an informing vision of history as a complex, ongoing field of events that occurs at eye level – of history conceived and portrayed as the cumulative actions of millions of ordinary human beings, living in historical time, growing up and growing old.(Dave Hickey, “The Kids Are All Right: After the Prom,” in Norman Rockwell, Pictures for the American People, ed. Harry N. Abrams (New York 1999).)

This declaration could also be understood as a non-ideological definition of Socialist Realism, with the sad reminder that growing old in the Soviet Union was a rather bitter and disillusioning process.

Artists from the two different areas of the globe idealized the world around them in order to advertise the values of the system they belonged to, making these values even more clear and comprehensible.

Some of Rockwell’s American viewers also sensed that they were being fed propaganda,(For example, Neil Harris writes, “For a second source of anxiety [from Norman Rockwell’s art] was my growing sensitivity to pictorial propaganda, perhaps even some faint association of the poster-like good looks and rural charms dominating Rockwell’s pictures with images favored by Nazi (and Soviet) information engineers. In retrospect, it seems grossly unfair to link Norman Rockwell’s religion of American simplicity and informality with the art enjoyed by commissars and storm troopers, but, unfair or not, I made that connection. There was more than a touch of suspicion in my mind that I was being fed something so idealized as to be patently false.” See “The View from the City,” in Norman Rockwell, Pictures for the American People (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1999), 132-133. It is equally unfair to consider the art of Socialist Realism to be the creation of information engineers or the rule of commissars. In the end, artists were painting these pictures.) but in the end they did not seem to care that much.

They enjoyed these pictures for the stories they found amusing and enlightening, for the topics they were able to identify with, for the miraculous dialog that only art is capable of.

Today, Norman Rockwell is perceived as a tool of democracy and a promoter of understanding, glorifying the happy, utopian American life from the middle of the 20th century.

Rockwell spreads American values that we believe were better than those of the Soviet Union. He celebrated a political system that was tolerant of diversity while Socialist Realism never shows the coexistence of two oppositions in peace or in friendly dialogue.

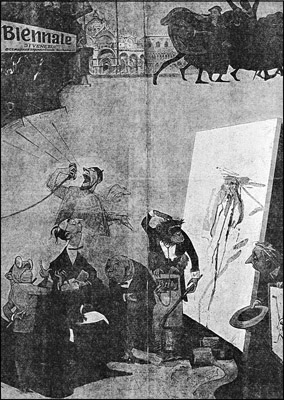

This difference can be beautifully illustrated by opposite reactions of Norman Rockwell and Socialist Realism to Abstract Expressionism. Rockwell was certainly far from being a fan of Jackson Pollock, but his version of dripping technique in his painting The Connoisseur is far from being evil.

It shows a new painting style just like another new and maybe puzzling element of modern life like television, atheism, or jazz music.

The cycle of paintings by Fedor P. Reshetnikov titled The Secrets of Abstractionism shows monkeys and donkeys splashing paint on canvases, while decadent critics and dealers are trying to sell them to bourgeois collectors. Figures of Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo are just crying in the background.

The fundamental difference between Norman Rockwell and Socialist Realism lies in the politics and unacceptability of Stalinism.

Unlike in art, it is as if the politics of Stalinism were the ultimate political kitsch: easy to swallow, pretending to have real value when in fact it is only a pre-processed imitation, a cheap reproduction that the Russian people, having few other choices, turned to in their despair.

And this is the reason why Socialist Realism seems to be doomed, at least for the time being.