Serbian Video Art in Focus: ARTTERROR—Fragments of Duality

ARTTERROR—Fragments of Duality, Belgrade Cultural Centre, April 5–May 3, 2018

The exhibition ARTTERROR – Fragments of Duality, on view at the gallery space Podroom of the Belgrade Cultural Centre, presented work by the Belgrade-based art association ARTTERROR created during the last few decades. However, as curator Vladimir Bjeličić and the artists themselves stated, the aim was not to show a retrospective of ARTTERROR’s work. Instead, Bjeličić noted that the exhibition should be “regarded as a specific installation or in situ reaction based on the critical self-reflection of this artist duo.”(See the leaflet accompanying the exhibition: Vladimir Bjeličić, ARTTERROR – Fragments of Duality (Belgrade: Podroom, Belgrade Cultural Centre, 2018), n.p.)

ARTTERROR – Fragments of Duality, Installation view. Photo by Lazara Marinković. Image courtesy of Vladimir Bjeličić.

ARTTERROR members are Milica Lapčević, a linguist and art historian, and Vladimir Šojat, a film and video producer. Šojat is the director and editor, while Lapčević is often the main protagonist in the duo’s videos. They are active as artists outside the ARTTERROR platform, and produce their work under the pseudonyms Lilie Ewgraphovitch (Milica Lapčević) and Maximilian von Dada (Vladimir Šojat). Lapčević works in different media, including painting, drawing, and photography, and has been also active as a curator. Šojat is an award-winning editor, who is mainly active in video art and has participated in numerous festivals and exhibitions around the world. ARTTERROR(The name reflects the drive of the artists to overcome and fight against all forms of normativity and established knowledge in art, and to create new art forms that do not reflect or cite those from the past. Vladimir Bjeličić, “ O videu, nezavisnoj poziciji i (umetničkom) otporu”, last modified October 6, 2018. https://www.beforeafter.rs/intervju/o-videu-nezavisnoj-poziciji-i-umetnickom-otporu/) was formed in 1989 as an open, experimental, and multidisciplinary platform dedicated to the production of short videos that vary in form and content. Their videos cover an array of subjects, such as history, philosophy, identity, politics, and knowledge production, which ARTTERROR approaches with a critical, often ironic distance.

ARTTERROR began producing their work in the 1980s just as video art in the former Yugoslavia started gaining momentum, as video equipment was not readily available to artists in the 1970s. Early art videos were recordings of performances and other artistic actions, often taken with a static camera; only later did experimentation with the medium’s technology become an integral component of video art.(Barbara Borčić, “Video art from conceptualism to postmodernism,” in Impossible Histories, Historical Avant-gardes, Neo-avant-gardes, and Post-avant-gardes in Yugoslavia, 1918-1991, Dubravka Đurić, Miško Šuvaković, eds. (Cambridge, MA: MIT press, 2003), p. 496.) This changed in the late 1980s with the rise of new social movements critical of the socialist system. Artists started to examine controversial and marginal topics, and video art soon became another archetype of alternative culture, as rock and punk music were already. In the 1990s, the country’s international isolation significantly affected the cultural scene, including video art. Some scholars note that this period was marked by “active escapism” in art, a term used to describe the “ideological character of the complete art scene.”(Lidija Merenik, “No Wave: 1992-1995,” in Art in Yugoslavia 1992-1995, Lidija Merenik, Dejan Sretenović, eds. (Belgrade: Radio B92, Fund for an Open Society, Center for Contemporary Arts, 1996), n.p.) However, the isolation and restricted access to the global art market did not prevent some artists from reaching beyond local issues.

Thematically and temporally, the development of video production in Yugoslavia, and later Serbia, corresponds with the broader East European context of video art, although there are some differences in how quickly Polish, Hungarian and Yugoslav video art developed in contrast to other countries in the region that were under stricter totalitarian rule, such as Romania, the Soviet Union, and East Germany. Characteristic of video art in Eastern Europe is that it recorded political and social circumstances through the technical specificities offered by the medium, while in Western Europe formal questions of the medium dominated video production.(Marina Gržinić, “Video in the time of a Double: Political and Technological Transition in the Former Eastern European Context” in Transitland, Video Art from Central and Eastern Europe 1989-2009, Edit András, ed. (Budapest: The Ludwig Museum- Museum of Contemporary Art, 2009), p. 29.) Thus East European artists sought to engage with politics by appropriating and using different historical and cultural motifs, including representations of the body. ARTTERROR’s work is one such powerful example. Their video art shows that thinking beyond geographic borders and engaging different time-space and subject positions can further elucidate one’s understanding of the present condition.

ARTTERROR, “Twinkle, twinkle, little star,” 1996, video segment. Photo by Lazara Marinković. Image courtesy of Vladimir Bjeličić.

The exhibition Fragments of Duality was divided into five segments, with each segment dedicated to a specific temporal and thematic corpus. The longitudinal space of the gallery offered a good framework for the display of ARTTERROR’s work in a temporal succession, rather than strictly separating each period from the next. The first segment, titled The Archive, showed some of the duo’s early works. Here, two TV screens positioned next to each other displayed the videos The Death of Mrs. Lenin (1989) and Chants of Mercy (1992). Both videos address social upheaval and ideology; the first one is inspired by the Russian avant-garde scene after the 1917 October Revolution; the second work takes viewers on an audio voyage through different historical periods, overlapping the unsettling sounds of various political unrests with a children’s song. The Death of Mrs. Lenin has a narrative structure, while Chants of Mercy is an early experiment in mixing unrelated audio and visual motifs, including shots of the figure of a woman and close-ups of the bare, grayish, and uneven surfaces of ceilings and walls, which resemble early black-and-white photographs of the moon.

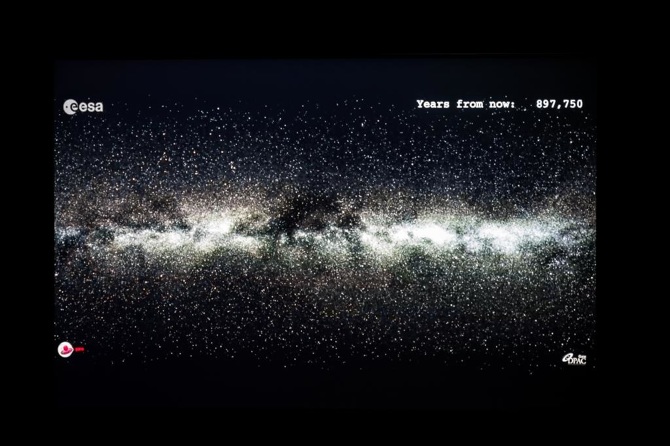

Although the audio element of Chants excavates troubled periods in history, its visual aesthetic of gray surfaces was an uncanny introduction to the second segment of the exhibition, Lessons About Universe. This section occupied the gallery’s largest area, located in a basement with no windows. The decision to leave the space dark, with just enough light cast mainly from the videos to navigate it, added an atmospheric, ethereal feel to this segment, which was comprised of several videos and black wall panels with texts about the galaxy, stars, and other cosmic elements printed in white. These videos and texts did not explore concrete historical events, but rather showed the aesthetic potential of the universe with its deep, black space and twinkling stars—shown in one video projected over the whole wall—as a pretext for philosophical explorations of transformation, contemplation, and travel.

Works on view in the third segment, appropriately called The Landing, returned to the earth and its problems. In three videos—Crocodile Tears (1997), H-eaven (2000), and New Land (2016)—the exhibition turned the viewer’s gaze to contemporary issues, such as regressive politics, the power of money, and the exploitation of labor in capitalism. The global and local collide in these works, but the references were somewhat difficult to discern without the artists’ commentary. For example, the sky shown in H-eaven is both the sky of climate change destroying the earth and the menacing sky showering bombs over Serbia in 1999. Crocodile Tears is about both an incident in New York from the late 1930s when a crocodile was discovered in the city’s sewers, and a crisis in Belgrade during the late 1990s when people took to the streets to protest political oppression. Both occasions drew special forces to the streets, creating a sense of impending danger and uncertainty. Disparate images – the sky, a crocodile, the former American President Bill Clinton, money, a piggy bank with a plastic crocodile head – mix in these videos. Together, they offer a clever visual interplay of symbols that invoke a sense of elation, danger, even fear, alongside thoughts about global politics and money that the artists link visually to a deadly predator. Finally, New Land is the artists’ take on leisure time under neoliberalism and the social segmentation it produces between those who enjoy it and those who work to make this enjoyment possible. The duo’s Vladimir Šojat is shown in the video siting uncomfortably between these zones—the upper zone of some resort restaurant and the lower zone occupied by a cleaning lady who sweeps the street in front of it—unsure of his position within the neoliberal system.

ARTTERROR, “Trinity RGB,” 2008, video. Installation view. Photo by Lazara Marinković. Image courtesy of Vladimir Bjeličić.

While all the works in the first three segments played with the technical possibilities of the medium of video through different themes, from the meaning of the universe to political unrest, the fourth segment, Digital Analogies, went further by explicitly experimenting with the technological aspects of video making. One video, Trinity RGB (2008), explores the relationship between tradition and technology by showing three figures (all played by Milica Lapčević) either interchangeably or all together on the screen with three different color accents (blue, red and green) that correspond to the colors in the television RGB signal system. The work links the body and technology by bringing the figure of the artist inside the technical world of the image, dissolving the line between artist and artistic material, between the embodied and coded worlds.

While the figures in Trinity RGB enter the screen as the materialized aspects of a technological world, the work in the last segment, The Body of the Message, uses the already existing and palpable form of the artist’s body and transforms it into a virtual one. The segment was dedicated to a five-channel video, also titled The Body of the Message, displaying fragments from several videos ARTTERROR created over the years, in which Lapčević is sometimes the main protagonist. The fragments are intercut with words and phrases that appear on the screens, such as “talented,” “Cyborg,” “money,” “theology vs. economy,” “world hunger,” and “how much paper zeros is your heart.” The central motif of ARTTERROR’s work is often the artist’s body, which is powerfully rendered across five screens in this work. Combined with words, the video installation brings the world economies of power and knowledge into a relationship with the aesthetics of representation: How does an artist position herself within such economies? And what type of art can be produced in relation to it?

The answers lie before us, fragmented and disharmonious, as the installation shuns any linear interpretation, and the viewer is invited to enter the work from multiple points of view and arrive at a range of conclusions. One such trajectory leads to feminist scholar Donna Haraway’s idea of the cyborg as the possible final reference of the fifth segment and the exhibition as a whole. “A cyborg is a cybernetic organism, a hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction. …The cyborg is a matter of fiction and lived experience… [and] the boundary between science fiction and social reality is an optical illusion,” states Haraway.(Donna Haraway, A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist -Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2016), pp. 5-6. See https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/english/currentstudents/undergraduate/modules/fictionnownarrativemediaandtheoryinthe21stcentury/manifestly_haraway_—-_a_cyborg_manifesto_science_technology_and_socialist-feminism_in_the_….pdf.) Through this lens, one might see the artist as intrinsically linked with the virtual reality she creates; nevertheless, her material presence reinvents this boundary between the living and the virtual world.

Fragments of Duality, Installation view. Photo by Lazara Marinković. Image courtesy of Vladimir Bjeličić.

ARTTERROR’s video art creates a strong statement about the changing social realities in which the artists immerse themselves. At the same time, these realities are transformed into fragments of technological data, sometimes too difficult to decipher if viewers are looking for straightforward answers. The expressive possibilities of the video medium make reality illusory, so that video becomes a complex set of data that oscillates between semantic readability and semiotic symbolism. Thus viewers of the exhibition were left to find the critical and reflective potential in each of the videos. Leaving aside didacticism or abstract materialism, Fragments of Duality provided a glimpse into almost three decades of ARTTERROR’s work and revived older pieces in a new light through the engaging installation, shunning the usual retrospective formula. In highlighting certain commonalities, it created connections between past and present and between different spatial and cultural spaces.

The exhibition also sought to exercise public memory regarding art in Serbia over the last three decades, and to raise questions about the lack of institutional systematization and broader interest in video art. While public memory remains crucial for the establishment of cultural and national identity, it is also a contested site of controlled knowledge. In Serbia, historical narratives have been privileged in recent large-scale exhibitions, while galleries and independent art institutions have provided space for more critically engaged practices. Fragments of Duality offered another perspective on such practices through the lens of ARTTERROR’s video art, and was a reminder that progressive and critical art flourished in Serbia, even if on the margins.