Sculptural TranscenDENTALism On Sculpture and Installation in Anselmo Fox’s Art

Anselmo Fox was born in 1964 in the Italian part of Switzerland (Mendrisio, Tessin). He studied in Luzern, in Basel, and in Berlin, where he has lived since 1994. His central artistic concern is sculpture, a genre which he treats in a wide medial spectrum, ranging from bronze to plaster, wax to chewing gum, photography to animated cartoon and video. Fox uses material appropriate to the form and space of his investigations, and he has thus processed a considerable amountof the amalgam alginat / alg-material usually used by dentists for teeth imprints. The oral cavity may be considered one of Fox’s territorial focuses. One may say it serves as a peculiar and truly avant-garde object, as a readymade sculpture, shifting itself back and forth on a level of geo- and physio-aesthetics. There are numerous exhibitions in Switzerland and Germany, former projects in Italy and Egypt. At present, Fox is preparing three contributions to an exhibition on figurative wax sculpture in Berlin. (“Waechserne Identitaeten: Figuerliche Wachsplastik am Ende des 20 Jahrhunderts,” [Wax identities: figurative wax sculpture at the end of the 20th century] Georg Kolbe Museum, Berlin, 1 June – 11 August, 2002. Contact: Anselmo.Fox@gmx.de)

|  |  |

On levels/plateaus and mountains

“The master had randomly piled the teeth, extracted by his art, without ever having had the chance to give attention to the irritating rubbish, the extermination of which he had been postponing. When working on his new project, he blessed his hesitation, now providing him with a useful and practical element.”

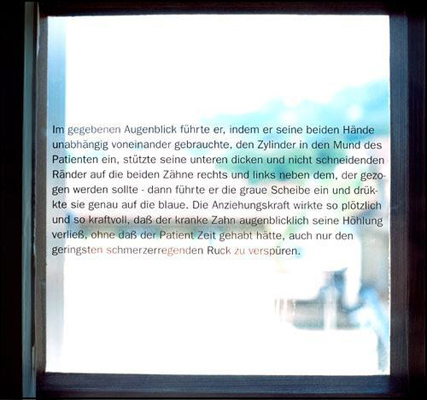

The installation named Le montagne te fanno vedere [The mountain makes you see](Raymond Roussel, Locus Solus (Frankfurt am Main, 1977), 53. (My English translation). This is one of the 12 quotations from the novel used in the installation.) was shown in 2001 not far from Luzern, Switzerland, in a residence dating back to 1784 and surrounded by the foothills of the Swiss Alps.(The installation was part of the exhibition called “Machet den Zun nicht zu eng,” celebrating the 25th anniversary of the Bruder Klaus Museum in Sachseln.)

Rather than the geographical context, it was Joseph Beuys’ environment called Voglio vedere le mie monatgne [I want to see my mountains] (1950-71) that inspired the title of Fox’s installation.(Cf. Joseph Beuys, Katalog zur Ausstellung Kunsthaus Zurich 1994 (Zurich: Kunsthaus Zurich, 1993), 140-47.)

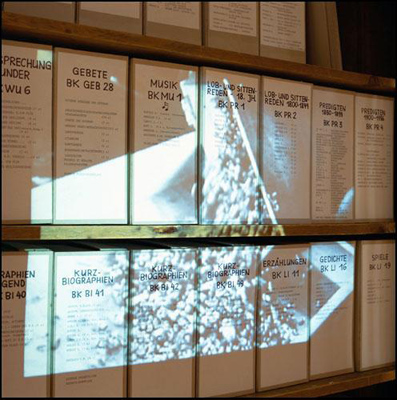

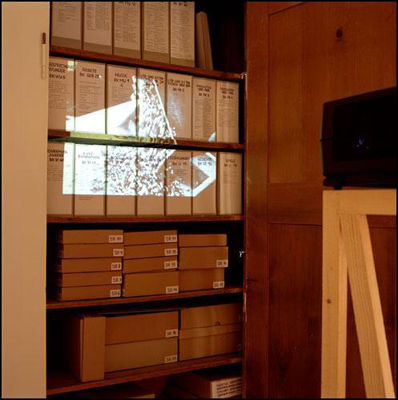

Le montagne te fanno vedere consists of three elements or, more appropriately, levels: the cloudlike sculpture made of molding marble, larded with about 500 human teeth; a video, projected on the spines of old files; and extracts from Raymond Roussel’s novel Locus Solus (1914), printed on transparent film and fixed to the windows that opened on a view of the mountains outside.

The spacious park area where the action of Locus Solus takes place is generated by a text continuously challenging the power of imagination, and it is this highly imaginative landscapethat constitutes the actual plot of the novel.

The reader of Locus Solus becomes a visitor to the park. In the second chapter of the novel, maestro Martial Canterel presents his pictorial mosaics consisting of human teeth. Canterel constructs his mosaics with the help of a special technique, developed by him for this specific purpose.

The technique is provided by “Demoiselle,” which consists of a complex machine floating upon the surface, picking up teeth and positing them at the exact spot. The super-sensitive mechanism reacts to weather and climate and depends on time of day. In addition, the Demoiselle enables Canterel to pull teeth without causing the slightest pain, thus establishing his enormous supply of human teeth.

The black and white documentary film shows an assortment of teeth poured onto a conveyer belt, from which they pile into a kind of hill-or a small mountain. As the looped sequence is reproduced jerkily, the movement and, consequently, the pictures, are alienated. They are projected on the spines of folders, labeled with inscriptions ranging from “SERMONS” [PREDIGTEN] to “HYMNS” [KIRCHENLIEDER] to “POEMS” [GEDICHTE].

|  |

The “teethcloud,” the cloudlike molded-marble sculpture, may be regarded as the central level of the installation. Its limestone-colored surface is laden with about 500 hundred human teeth. Three of them serve as the sculpture’s pedestal, giving the illusion of the heavy object floating upon the parquet, providing the imaginary impulse of movement, while, in fact, the teeth pierce the floor.

Synthetic hard foam was used to produce the raw form of the sculpture. The material, commonly used to fill up hollow space, shows difficult-to-control development in form, and distends arbitrarily. In order to shape the sculpture’s form, it was removed in the working process of casting and remains as hollow space, as the cave of this paradoxical cloud.

The cloud, representing the light, the diffuse, the unlimited, the volatile, and the chaotic, subject to climatic conditions, has petrified into a singular fossil cosmos. Rather, the innumerable is represented by the huge quantity of teeth, again exteriorizing the characteristic features of the cloud. Nevertheless, we have access to interior space, as the sculpture is fractioned at one side, providing insight to nothing but darkest “night.”

Insight and horizon

Extraction, incorporation, insight into (the) nothing, and, as the artist calls it, “a lower horizon,” may be regarded as the basic aspects of Fox’s art. The area of visual perception is deterritorialized, transferred to the lower (and deeper) level of orality. Thus, the artist has been dealing with paradoxical insights into the oral cavity, transcending the petrified boundary between medical requirement and aesthetic ban, both of which mark this anatomic territory in Western culture.

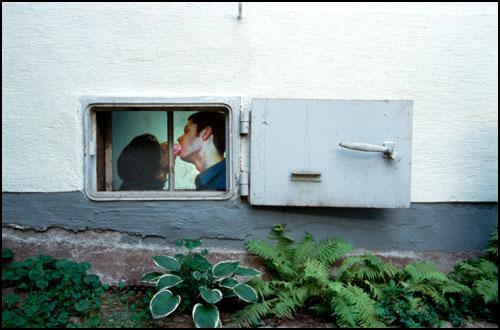

Fox has been pioneering the infernal interiority by, for example, focusing on the sculptural traces-i.e. impressions-of the French kiss. These aesthetic investigations literally transcend the topographical relationship between exteriority and surface, giving form-casting paradoxical transitions. Purely anatomically, it becomes obvious that the dental system has grown subject to Fox’s interests likewise. Markingthe borderline of the oral cavity, the teeth literally stand for the transcendental-referring to the aspects of the deeper horizon mentioned above.

|  |  |  |

The installation contextualizes the vast amount of teeth with their “original” anatomic, physiological, economic, and aesthetic functions. In its natural corporal reality (copor(re)ality) the single tooth functions as part of a system. Teeth serve incorporation (the masticatory apparatus) as well as expression (the phonetic function). Singular or even complete absence causes dysfunctions, pain, and expense, not to mention aesthetic defect (think of the veritable history of dental fashions).

|  |

In addition, the teeth contribute a good deal to indirect communication (think of “Dracula” or similar bestial threatening gestures, not to mention the perfect smile). Thus, very obviously, the single tooth not only functions but gains its value in correlation to the dental system, and it is deprived of both function and value whenever extracted-singularized-except for becoming part of a secondary system of value (think of trophies, relics, or the superstition regarding milk-tooth).

Imaginary added value

Let us now turn to the aspects of aesthetic revalorizations provided by the installation, the transcendence of tooth value. The extracts from Locus Solus focus on the pictorially aesthetic aspect: The mosaic shows a soldier who has fallen asleep in a grotto. The text visualizes the soldier’s dreams that are becoming part of the narrative.

The individual tooth’s coloring provides for the pictorial representations of the mosaic. Remember that white is the ideal color of the human tooth; consequently, the picture, the aesthetic product, is caused by aesthetic defect in the primary system. The text itself draws attention upon a blue tooth, adding a “new indigo blue spot” to the mosaic, while emphasizing the blue tooth’s similarity to the one causing the sole defect to the otherwise ideal beauty the Duchess of Castiglione was famous for. The attraction of defect in the Duchess’s perfectly attractive appearance has been transferred into an invaluable effect in the mosaic’s quality.(Roussel’s (1877-1933) novel Impressions d’Afrique was first published in French in 1965. According to Colin Raff, Roussel’s novel inspired MarcelDuchamp’s “Large Glass” (Colin Raff, http://www.nypress.com/14/19/books.cfm).)

There seems to be hardly any level of transcendence in the documentary film, which refers to totalitarianism and the terror of the Nazi system, aiming to retain value from the potential treasure of tooth gold. Subtle treatment of the moving pictures, however, reproducing and witnessing the unimaginable, manages to interfere, at least as far as the horizon of perception is concerned.

Due to specific manipulations, the video’s pictures move forward in an uneven manner, producing abrupt photograph-like breaks, a moment between movement and stasis. This technique may be called “decadrage,” a term used by Gilles Deleuze. This manipulation, affecting the temporal quality of the moving picture, causes the viewer to gain the visual impression of seeing the single picture, and, consequently, the single tooth, extracted-excorporated-from its individual topos: the individual human body. The picture undergoing such distraction assumes the imaginative option of reincorporation.

Nevertheless, this surplus of time, the unlikely rewinding of history, remains nothing but illusion-the documentary film keeps moving on in loops. Between mass and intimacy, extermination and selection, the single tooth, its shadow’s ornament, is re-archived, projected and reprojected into and onto the intimacy of the opened cabinet, holding a sacral archive. The factual black and white of the documentary undergoes fractions, and visualized and imaginable shadows add some kind of supplement, which one could think of as the maximum of impossible coloring that can be added to the (hi)story to which the pictures refer.

Transcendental Incorporation

Let us finally return to the sculpture, the cloud fallen from sky.(For more on cloud and art history, see Hubert Damisch, Theorie du nuage. Pour une histoire de la peinture (Paris,1972).) The various levels, indicating instability of value systems, have been reincorporated on the surface and in the paradoxical substance of the sculpture.

If we focus again on the teeth, we are struck by their individual sculptural quality and their anthropomorphic appearance. The color is subtle, and there is still the enormous contrast between the white marble-like surface (sprinkled with black) and the teeth, which tend to be every color except white, predominantly yellow; we find fascinating spots ranging from black and red to green and brown.

As far as the corps and corpus are concerned, we cannot help but realize that the sculpture’s material alludes to the antique and classical human sculpture and statue-conceived in white marble. It is an imagination that proves its volatile reality and corpo-reality in the various modes of espacement and extraction, represented by the installation in general, as well as the sculpture in particular.(Cf. Hartmut Boehme, “Erkundungen der Mundhoehle: Zur Kunst von Anselmo Fox,” in Neue Aesthetik: Das Atmosphaerische und die Kunst, ed. Ziad Mahayni (Munich, 2002), 15-33.)

If we trace teeth back to a system, one which indicates the unsystematic and chaotic, it may be seen as an aesthetic reincorporation, paradoxically petrifying aesthetic, anatomic, climatic, and historical dislocations and translocations.(Gilles Deleuze, Das Bewegungs-Bild. Kino 1 (Frankfurt am Main, 1998).)

Here again it shows how a “lower horizon” can arise-contrary to physical and aesthetic canon-via an aesthetic which is more than-and anything but-a contradiction: it is as affirmative as it is transcenddental.