Roundtable on Art and Solidarity

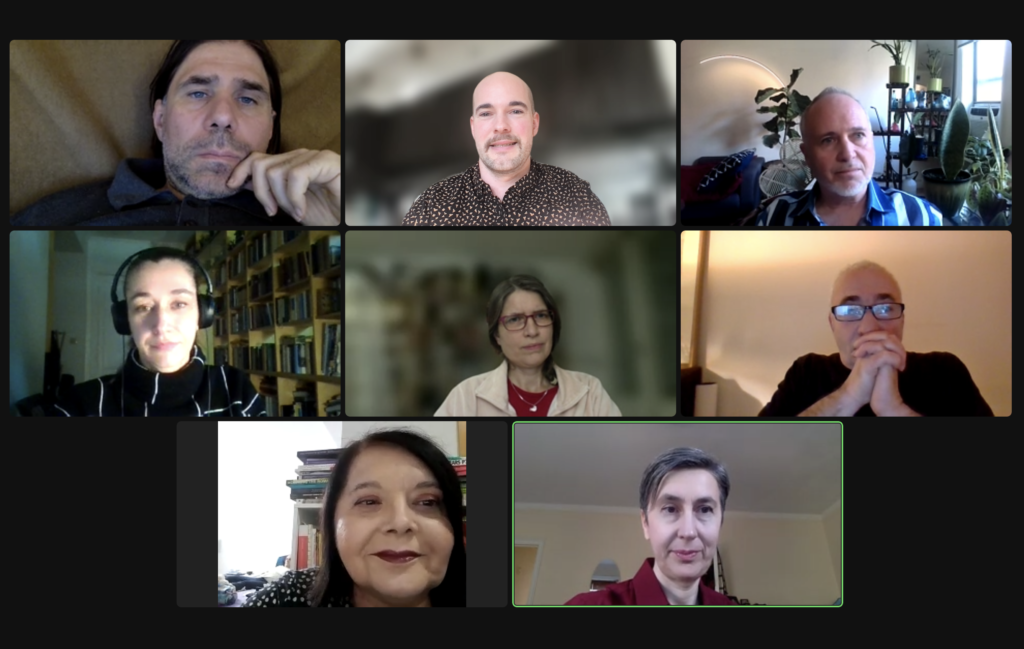

The following roundtable was convened online on November 18, 2022, in conjunction with ARTMargins Online’s current special issue on Art and Solidarity. AMO’s editorial collective invited a panel of East European artists, theorists, and curators (Suzana Milevska, Olga Kopenkina, Dmitry Vilensky, Rena Raedle and Vladan Jeremic) who all have consistently engaged with the dilemmas of defining and practicing artistic solidarity. We asked participants to examine the forms and interpretations of solidarity they find the most effective, why expressions of international solidarity often fail, and what lessons the legacy of socialist internationalism may have for us today.

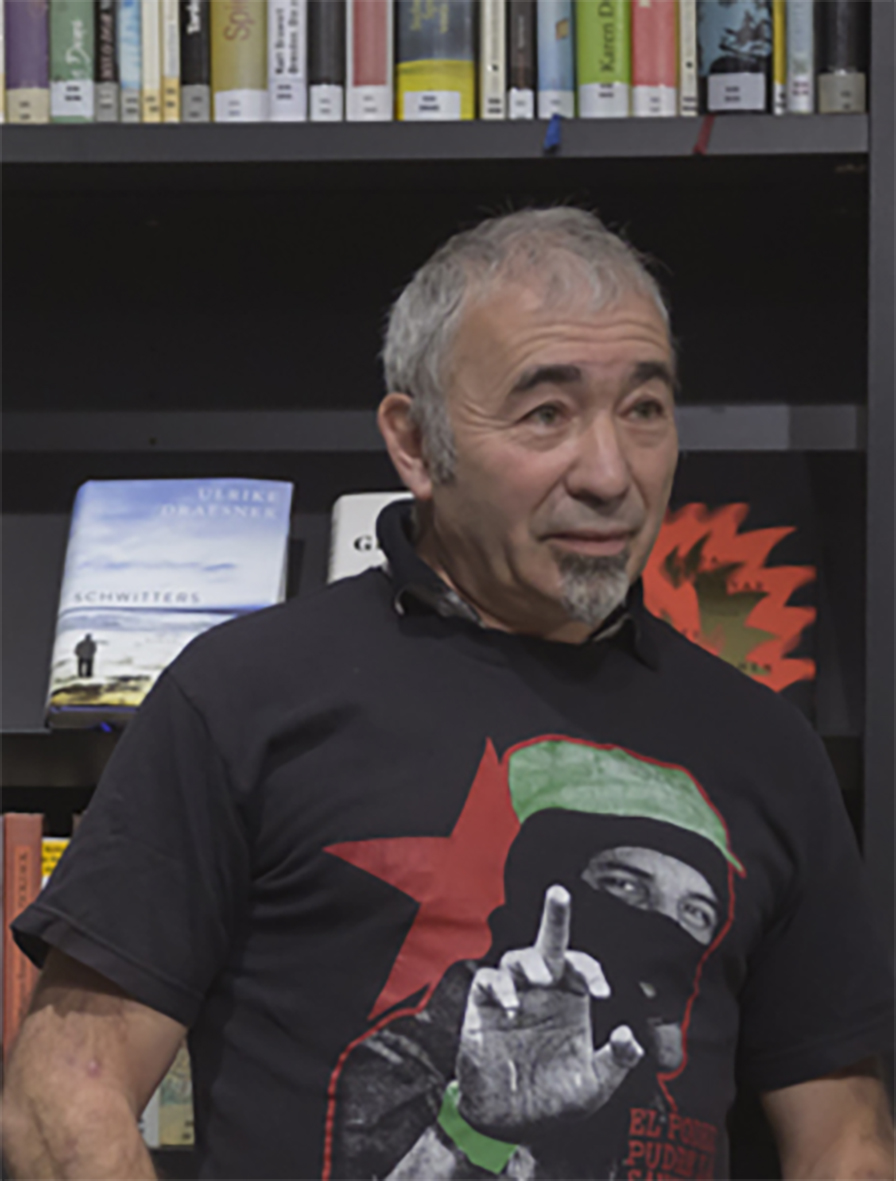

The online conversation moderated by Gregory Sholette, a New York-based artist, activist, and renowned author on art and activism—calls attention to the geopolitical limitations and determinations of solidarity exemplified by art projects and related debates, protests, and withdrawals. Panelists also shared their experiences and insights on how acts of solidarities are defined or are detached from historical uses or abuses of the term, the actors’ nationality or nationalism. Finally, what validity does critical reflections of solidarity have in times of urgency and crisis?

Gregory Sholette: I wanted to start off with a quote about the concept of solidarity by Syrian political commentator Yassin al-Haj Saleh: “The structure of the world, divided into flourishing metropolises and floundering backwaters, underlies the solidarity relationship, and determines its direction. The effect of this structure is not lessened by the fact that the theater of solidarity is exclusively in the West, even if the ‘raw’ causes come mostly from outside it.” (https://aljumhuriya.net/en/2018/05/18/a-critique-of-solidarity/)

I think the main point here is the uneven relationship between those who are looking for or receiving solidarity, and those who are giving solidarity. Could we begin by defining what we think of solidarity, and also thinking about this quote?

Suzana Milevska: The most important question that we could start with is whether all solidarity is positive. We assume somehow in the West that solidarity, in any case, in any context, is positive. I feel some discomfort with this assumption because it’s based on a unified concept of solidarity. It’s important to go further and to ask: solidarity with whom? which is very similar to the quote that you just read. I suggest that we should begin by distinguishing between solidarity with the similar and the same, and solidarity with the different.

I wrote several texts about solidarity, either between academics and activists, between artists, curators and other members of different disenfranchised or vulnerable communities like refugees or Roma people. There are different kinds of solidarity. The danger with solidarity with the similar is that actually it may go in the opposite direction, for example, in the direction of nationalism.

If you are in solidarity with someone similar to you, it’s contradictory to this positive assumption that you said, Greg, at the beginning. It’s a no-brainer. I was inspired to think about this, but through the ideas of Paul Gilroy, who mentioned, a long time ago in one of his interviews, that the problem with this otherness is that the other is vulnerable in our societies. (Tommie Shelby, “Cosmopolitanism, Blackness, and Utopia: A Conversation with Paul Gilroy,” Transition 98 (2008): pp. 116–35.) The other according to Gilroy is conceptualized both as a problem and as a victim. (Paul Gilroy, There Ain’t No Black in Union Jack: The Cultural Politics of Race and Nation (Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press, 1991): pp. 11-12.) If we face this kind of inner contradiction, then it’s becoming even more difficult to answer the question with whom we should solidarize. We should be aware of this danger of solidarity as a unifying concept that hides or covers many different contradictions exactly in the same line as the quote you read.

Rena Raedle: What caught my attention in Greg’s quote was “the theater of solidarity.” The word solidarity or the concept of solidarity was very much attached to the workers’ movement. A phrase or a pragmatic idea about what class consciousness could be. The practical value behind solidarity would include all those negotiations, who is actually solidarizing with whom and what are the structures we are using for solidarity work. This is always in danger of becoming appropriated, or in Marxist terms, objectified, in the meaning of reification. Solidarity is becoming a commodity that can be attached to a certain action or even a person. Think about this new habit of attaching a “solidarity button” to your profile picture in Facebook for a special cause. It’s becoming a kind of currency to declare your solidarity, especially when it’s attached to consumer goods. It becomes part of a consumer culture to buy products that declare solidarity. The opposite would be a boycott of certain goods. So there can also be a market mechanism linked to the act of solidarity.

In socialism, this term was emptied out. It became a phrase of declarative expression that replaced the idea or the concept of class consciousness with something very simple. You could just put it on as a badge. We can only escape from the “theater of solidarity” if we really go into looking at the practices of solidarity.

Olga Kopenkina: In response to what Suzanna said earlier about solidarity as a term and a kind of practice that can turn out badly. I have a totally opposite approach because my understanding is that solidarity is not something abstract and generalized. Solidarity has particular goals. With regards to Belarus and the two-year-long protest that started in 2020, all kinds of solidarity campaigns happened and are happening right now because of the prosecutions, tortures, and continuous harassment of Belarussian citizens. But the moment that drew the attention of international communities to Belarus has faded away. This is the most dangerous situation for Belarus because the prosecutions continue, but the attention is not there any more. Belarussian expats, and artists are among them, are trying to bring this attention back and keep Belarus on the agenda of government and non-government organizations. For me, a solidarity network in such a situation can be based on whoever feels in solidarity with Belarussians, if they can join, support, or help, regardless who they are.

Ten years ago, when I organized the exhibition, “Sound of Silence: Art during Dictatorship” in New York, with artists from Belarus, who addressed anti-government demonstrations and support for political prisoners in Belarus, it received much less attention than such projects get today. (https://www.projectspace-efanyc.org/sound-of-silence-art-during-dictatorship-1) Now there are various art initiatives, compared to ten years ago when such an exhibition was almost like the only one in Western Europe and United States. Today’s solidarity projects are small-scale, and they mostly rely on galleries or universities, and I don’t see any organized action on the side of the international art community. Biennials and other powerful institutions and museums are still a missing link in this network of support. Of course, protests and campaigns are horizontal and should not pivot on big institutions, but museums and biennials can use their power to integrate community struggle in the mainstream arts discourse, which can have a serious diplomatic impact, but they don’t do much, unfortunately.

The Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York runs a global research project, C-Map, which often focuses on East and Central Europe, but before this war, it has never focused on Belarus, or Ukraine. (https://www.moma.org/research-and-learning/international-program/global-research) They discussed Russian art a lot, and of course, it’s also because they’re dependent on Russian money. They organized field trips to Russia and created a curatorial residency for a Russian curator at MoMA, sponsored by an oligarch’s money. Now MOMA has a room, directly in the exhibition of the main collection, in which they show the 20th-century avant-garde artists, who were born in Ukraine. (https://www.moma.org/calendar/galleries/5454) Their magazine also published a few articles in support of Belarusian protests and persecuted artists in Russia, and they also published on Ukrainian LGBTQ communities (https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/752), but they don’t really integrate these issues deeper in their programs.

Meanwhile, the international art community was able to organize great support campaigns, with museums joining them some time ago, on behalf of famous artists Ai Weiwei and Tania Bruguera, who were arrested respectively in China and Cuba. These campaigns were successful because they used the mechanism of cultural diplomacy to press the authorities to release the artists. However, solidarity campaigns might not be effective, if they are to push autocratic governments; it depends on what stage of insanity the regimes are.

In Belarus, artist Ales Pushkin has been in jail already for a year and half for exhibiting a painting. (It was a portrait of a soldier, Yauhen Zhykhar, who participated in the anti-Soviet post-war underground movement in Belarus. Puskin was accused of “committing deliberate actions, aimed at rehabilitation and justification of Nazism.”) But I don’t see any kind of organization or solidarity campaign to release him – neither in Belarus, nor by the international art community. With regards to Suzana’s argument about with whom you are in solidarity, here’s a dirty little secret: Ales Pushkin is a Belarusian nationalist. I guess this is what stops people from organizing a campaign to support him. This is similar to what had once happened to Alexei Navalny, the well-known Russian opposition leader imprisoned by Putin. Amnesty International pronounced him a prisoner of consciousness, but later revoked this title based on someone’s claim that “he’s a Russian nationalist” (the status had been returned after some clarifications). Too much for solidarity.

In the context of the solidarity campaigns with Ukraine, when we start questioning who we are in solidarity with, it can actually undermine solidarity because of the sporadic boycotts against Russian artists and colleagues, including, unfortunately, against those who were consistently in opposition to Putin’s regime. All this echo-chambering—everyone is sitting in their own camps and talking only to each other—can prevent us from working together and creating effective solidarity networks.

One example that comes to mind is the online project Antiwar Coalition (https://antiwarcoalition.art) a solidarity campaign with Ukraine through art, launched by Belarusian curators living abroad. It’s based on an open call: those who want to support Ukraine can upload their art on the project’s website, and then the curators decide if they want to keep it, or not. When during a panel discussion on Zoom, Anna Chistoserdova, a co-founder of this project, was asked whether Russian artists were welcomed, she answered that they didn’t want artists from the aggressor country to participate. Coalition means a partnership between political parties or groups to achieve a certain goal. It means you ally with someone and don’t ally with others for whatever reason. They are probably effective in military campaigns, or the political field, but I don’t think that they work in the cultural field. We need open solidarity platforms, open campaigns, and we need anybody who feels the same way, to join.

GS: You’ve opened up the next set of questions around culture, its effectiveness, its ineffectiveness.

Vladan Jeremic: To come back to the origin of the term international solidarity, it started around the 19th century with European support of the Greek struggle for liberation from the Ottoman Empire. (Caroline Moine, “Feeling Political across Borders: International Solidarity Movements, 1820s–1980s” in: Feeling Political: Palgrave Studies in the History of Emotions (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2022) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-89858-8_11) So it is historically connected to nation-building and nationalism, we cannot deny that. With workers’ solidarity and connecting solidarity to class consciousness, as Rena mentioned, its historical notion changed at the end of the 19th century. Then, after the Second World War, in socialist states, the so-called international solidarity and the struggle for independence in Africa and Asia became a prominent socialist perspective, which also completely changed the notion of what international solidarity was.

This kind of international solidarity, at least on the level of the United Nations and global politics, is gone because socialism is not on the stage any more. Predominantly, today we can face the interests of the elites in each country and competition between them. The question is what kind of practices we can, as artists, offer and support, and what is then the distinction between partisanship and solidarity? It might be that sometimes we need real partisanship rather than only expressing solidarity.

OK: Can you explain why a cultural solidarity campaign qualifies to be partisanship?

VJ: Sometimes we need to distinguish between partisanship and campaigning, and between a solidarity declaration and some kind of charity, when you just donate money. I am not suggesting that we shouldn’t name these donating campaigns a solidarity practice, because donating is also part of it. I want to emphasize that we need to be aware of when donating funds, or staying on the level of petitioning and sharing messages on social media may be productive, and when we should rather act multidirectional in order to achieve a certain political goal. You mentioned so many cases where people are still in jail. I just remembered the prominent figure and supporter of Turkish arts and culture, Osman Kavala. (Osman Kavala is the founder and supporter of arts and culture NGOs in Turkey. He was sentenced to life in prison in 2022 for financing the anti-government protests in 2013 and the failed coup attempt in 2016.) Unfortunately, international solidarity did not help him yet. We need to distinguish between charity, solidarity, and partisanship.

Dmitry Vilensky: It’s interesting that we have started with a serious critique of solidarity. Cultural people always criticize whatever comes to hand. I would focus on the celebration of solidarity, and speak more from a psychological perspective. Even if you are in jail and receive a hundred letters a day, you feel much stronger than if no one remembers where you are. If you receive some money on a common wallet and you can buy some food in jail, maybe you won’t be released, but at the same time, you feel much better.

I absolutely agree with the differentiations, especially in relation to your quote about solidarity that triggers a critical approach. Still, solidarity can also be an emotional affiliation between people who share a certain affinity. It could be a national liberation struggle, like in Ukraine, or an anti-colonial movement or class-based. Though I see a division when we analyze the old concept of classes. What is solidarity for us as artists, as a practice?

GS: If I could just throw in one comment. Going back to the days of the US war against Vietnam: Vietnamese people always tried to reach out to the opposition in the United States. They always tried to encourage and inform them. They didn’t try to cut off the US people. But let’s talk a bit more about the question of culture. What seems to be possibly effective, what is not effective? What is the role of culture as opposed to power, politics, and material support?

DV: Our collective and artists in general work mostly with the production of symbolic, artistic values, and knowledge. The main way to demonstrate our solidarity is to insist on sharing resources, making visible some marginal communities and their struggle for recognition. It makes sense to distinguish our artistic and professional activities from our actions as a people. When we sign and organize petitions, transfer and collect money for prisoners, and participate in protest campaigns, we usually act as other people. Maybe we make posters but not as an artistic statement.

For us, the most urgent and challenging expression of solidarity is to make visible the many people in Russia who stay in solidarity with the armed fight of the Ukrainians. We openly supported them with our statements, by providing financial help, and tried to maintain direct human contact. We very often deal with the politics of commemoration. For us it is a politics of solidarity with people who are still alive and those who are dead. Your solidarity with the dead marks your political position and affiliation. So we try to actualize forgotten struggles, unknown heroes, and situations of the past and make tributes to them. Compared to pragmatic solidarity, which demonstrates unconditional character like unconditional hospitality, artistic statements can be more complex and keep a certain form of critique. At the same time, the process of critique keeps the horizon of solidarity despite some political, ethical, and emotional contradictions, which should rather be revealed and not hidden in the artwork or critical text. I would name it as an expression of comradeship, which includes critique and sometimes disagreement, but also clear support. We stand together despite our differences.

We should also consider not just the particular clash between Ukraine and Russia, but go deeper into the psychological ambivalences of cancel culture. So if one is canceled you can’t escape (the consequences). There is no redemption, and this is a very interesting contemporary state of mind: a politics without redemption. In Marxism, you can even make a qualitative jump: from bourgeoisie you can become proletarian, but you cannot become Ukrainian because you have a different passport, you remain a violent person per se (a representative of an aggressive country).

SM: This is exactly the example when many people were cautious about being in solidarity with Russians who are in solidarity with Ukrainians, which is in this context the “different.” I want to clarify my own position: I always start from a feminist position. At the beginning of feminist movements, the solidarity with the same, with white, Western women was dominant. This was the biggest problem of women’ solidarity within the first “white” wave of feminism. Perhaps, in this context we can introduce intersectional solidarity.

GS: Another question relates to the context of neoliberalism that we’re operating within. Sometimes it appears that we’re in a situation like in the First World War where major capitalist powers vied for slices of the resources of the planet, including labor. We also know that the neo-liberalized economy deals very much with symbolic, visual, aesthetic politics. As artists, we’re right in the middle of it. What specific role can contemporary art play in solidarity movements, especially with a view to our neoliberal present, the nature of the neoliberal global art world?

RR: I was using this term of solidary artistic practices in a recent publication. (https://raedle-jeremic.net/art_within_political_struggles.html) I used it to describe practices in the Balkans that are long term and connected to concrete aims in solidarity with the struggles of the local community. They’re very concrete, very much directed towards creating infrastructure with small steps over many years. They work on creating space for culture production or for anti-discriminatory social struggles. Artists don’t do these to produce an artistic outcome, but most of all to really immerse themselves into those negotiations and processes and contradictions. Sometimes only after many years and as some kind of side project, the artistic production comes along. So the whole process cannot only be attached to an artistic project. It’s a social process. I choose the term solidary artistic practice to mean something that is deeply rooted in social relations. Whereas I would rather place solidarity campaigns into some kind of political lobby work or cultural diplomacy. They are not actually working on real social relations or on the advancement of everyday social relations.

In our artistic practice, the notion of solidarity would be much more linked to such small steps, to creating networks, gathering activists together, researching common grounds and interests, and creating a common language and consciousness about what we are doing together. When we speak about our working conditions in the art field, it isn’t wrong to say you should be in solidarity with the same. It’s much more of a challenge to be in solidarity with the different, that’s clear. But I wouldn’t hierarchize solidarity. I think it’s a two-way process, a relationship that needs to be built from both sides.

SM: The context of the discourse of race and privilege, when the same is the same nation or race, that’s where I would rather be more critical.

RR: I completely see your point and agree with this critique, of course.

GS: We’ve brought up Ukraine and Belarus, but haven’t talked about Iran, which is going through a phenomenal situation at the moment. And Syria, which is why I began with the Syrian author because the response to their crisis has been very different in the United States than towards Ukraine. This has been commented on a great deal, and there is an ethnic or racialized aspect to that.

DV: We can also translate new forms of solidarity in care work, communities of care, the process of caring, caring for others. I know it’s a buzz word right now. We should stipulate the difference between masculine, patriarchal forms of solidarity, and the feminist modes of care, to which we should turn. It was already manifested in many campaigns, like Women in Black (https://womeninblack.org/) or in Argentina, where women take care of prisoners. It was the same in Russia during the first Chechen war. The main approach to solidarity is continuation of life. Here we can also link with your original question about the neoliberal condition. First of all, with denial of neoliberalism, because neoliberalism is necropolitics, and very global. The only way we can resist and survive, even if it’s still a very marginal practice, is the politics of caring for each other.

GS: One other direction is the question if any of that discourse inherited from the era of international solidarity around socialism or labor solidarity is symbolically or otherwise useful now. Or is it so discredited that we really have to shift towards care or some other alternative?

OK: I don’t think that care is necessarily opposed to neoliberalism. The politics of care depends on the context. There are indigenous forms of care, and as you mentioned, the actions of Chechen women, Women in Black, and women in Argentina and India there are plenty of examples we can find. There is also a politics of care that is embedded in the neoliberal society because many things are done in the name of care, even wars are waged in the name of care, as it was said in the case of Ukraine.

GS: Are you speaking specifically about the monetization of care or for example, the way say Filipinos are exploited in the United Arab Emirates? Dmitry was talking about a concept of care that was somewhat at odds with the notion of monetization.

OK: What Dmitry was talking about are more indigenous forms of care rooted in localities that emerged from real connections between people in the time of emergency.

GS: Maybe I could thread the needle a little here and come back to the question about the history of socialism, Marxism, and solidarity around the idea of labor. For example, wages for housework that emerged in 1970’s Italy and elsewhere. Sylvia Federici, who specifically raised the critique that Marx’s analysis of capital talks about the reproduction of the workforce but doesn’t talk about who reproduces the workforce itself: women and women’s work. It has opened up gaps within the Marxist framework, but that of course leads us to the question of care or service or a demonetized solidarity amongst human beings. But there’s a danger of naturalizing that, and I think that was precisely Federici’s point, that Marx and others had basically naturalized that type of work, just taking it for granted as part of the process of reproduction. Maybe we could ask again, what, if any lessons or possibilities are there from this history of solidarity that emerged in the late 19th century, early 20th century?

RR: Obviously, the Left’s idea about solidarity was connected to international solidarity. If we think about the humanitarian project of the Workers International Relief (WIR) that was formed as a response to the big famine in Russia in 1921. This was maybe the biggest Left international solidarity campaign. It was, at the same time, also used to bring internationalism to the workers. This idea that there are other workers or other people somewhere far away, and that we become active subjects to help them. This was a big propaganda move as well. Today we can see that it’s actually the Right that succeeded in claiming this social engagement in communities by donating food and taking care of all the existential problems. This is something the Left needs to get hold of again. We have the problem that the Right is better at organizing solidarity networks on the ground. The only counter-action would be, and here I come back to what you said, Suzana, is to connect solidarity with this acceptance or care for the other, not the same, single form of solidarity but a plural form. This would be the new Left / old-new Left perspective on solidarity. It’s always the question how the word solidarity can be filled with action.

SM: When we go back to the art world, there is a certain kind of contradiction within the system. The art system that doesn’t allow these distinctions. When we speak about biennials and solidarity with certain artists who felt hurt or wanted to boycott an exhibition or institution, then neoliberalism becomes very pertinent because all these professional artists and institutions somehow belong to this neoliberal world.

Assuming that the artist can be on both sides doesn’t work. If you are in solidarity with certain artists and institutions that are part of the neoliberal world, the contradiction is that you, by default, become in solidarity with neoliberalism. I had in mind these contradictions at the beginning of our discussion: how to be in solidarity without actually recuperating and enforcing the neoliberal system. You can easily find yourself on both sides of the problem. You can’t have cake and eat it too. To understand with whom you are in solidarity, you really have to know more.

For example, at the 19th Sydney Biennial, an important case happened in which nine artists led a boycott against the company Transfield. They withdrew from the biennial, but the situation didn’t change much. One person resigned from the board, but they found another one. They renamed the company, but the problems remained. (In the February of 2014 artists Libia Castro, Ólafur Ólafsson, Charlie Sofo, Gabrielle de Vietri, and Ahmet Öğüt, Agnieszka Polska, Sara van der Heide, Nicoline van Harskamp, and Nathan Gray withdrew their participation in the 19th Sydney Biennale to boycott its main supporter, Transfield, a company that manages manages mandatory offshore detention centers for asylum seekers in Australia. As a result of the boycott Luca Belgiorno-Nettis, the chairman of both the Biennale and Transfield company, resigned from his position at the art institution, but the biennale did not cut ties with the family and still relies on government support.) It is easy to say that you’re in solidarity with Ukrainian people but when we bring this concept of solidarity into the art world, I think the situation is more complicated. This is why it is really important to clarify the distinctions between solidarity as a political action, which I think it is, and this old concept of solidarity, what the Right appropriated and what the Left can do about it. At the same time, the inner contradictions in the art world between institutions, independent artists, and artists from different geopolitical situations are not so easy to unravel.

I went to the Berlin Biennale this year, and I am still questioning this situation with French artist Jean Jaques Lebel’s work with images of Abu Ghraib prisoners. (https://12.berlinbiennale.de/artists/jean-jacques-lebel/) I have no instrument to discuss this. It’s not about art anymore. It’s about visual culture and visual activism. Three Iraqi artists, and a curator who worked with them objected to the chief curator, Kader Attia, about this work and the Iraqi artists withdrew from the Biennial. (The protest was started by the article of the Iraqi curator, Rijin Sahakian, who contributed to the Biennale as an advisor and author of catalog texts: “Beyond Repair: Regarding torture at the Berlin Biennale” ArtForum, July 29, 2022 https://www.artforum.com/slant/regarding-torture-at-the-berlin-biennale-88836 Three Iraqi artists, Sajjad Abbas, Raed Mutar, and Layth Kareem withdrew their works from the Biennial.) I attended the Berlin Biennial the last day before it closed. There was no sign of the boycott in the space. Obviously, this neoliberal institution, the Biennial, which is very powerful, did not really care about this criticism, nor did they address it within the space. The artist himself, Lebel, didn’t make, as far as I know, any statement in relation to the people who felt hurt by his work. I’m still divided, split. I have no proper theory or instrument with whom to be in solidarity with. If you ask me personally, I have, of course. But my theoretical concepts somehow are limited and get muted. I haven’t yet developed instruments about how the artworld can express solidarity without cutting the branch on which they’re sitting, because solidarity and taking sides may often result in cutting the connections with the Berlin Biennial, the Hamburger Bahnhof, these huge, relevant, important, powerful institutions.

VJ: In the context of neoliberalism and the complex global situations and problems, I want to mention ArtLeaks Assembly, an art platform we started twelve years ago. (https://art-leaks.org/about/) Dmitry was also part of it, as well as Corina L. Apostol and others. We opened the space for investigating globally the blacklisting of artists or abusing their professional integrity or infringing their labor rights. Through this practice, we built a solidarity network with people who were able to respond to those cases. The best quality of this platform was building a solidarity network gradually through practice and not demanding immediate solidarity, but to provoke it, to produce it. In a lot of cases, we succeeded, at least in providing some answers and defending several cases. Due to the fact that traditional trade unions and local artist unions in nation states and within the local contexts are not functioning well, ArtLeaks and other global solidarity networks have been very important in protecting labor rights of artists and cultural workers. My lesson from that is that we have to build solidarity through time and we have to work on it gradually.

DV: It’s good that we are discussing practical and concrete cases such as the situation around the Berlin Biennial. We sometimes miss the full picture. I would bring up the most heated debate around solidarity in Germany, in relation to the curators of the current Documenta and the accusations of anti-semitism. That was an amazing campaign, which revealed all kinds of local features of neoliberalism and national politics and politics of the past in Germany. At the same time, the support was quite strong and demonstrated the potential of the community to discuss and elaborate critique. People said it was a mistake, but at the same time, despite the mistake, they made an incredibly important statement.

I would like to bring to our attention the 2017 Whitney Biennial where Dana Schutz exhibited her painting, Open Casket, which provoked the protest of artist Hannah Black, among others. (The painting depicts the open casket funeral of Emmett Till, a fourteen year old African American boy murdered in 1955. According to Hanna Black “although Schutz’s intention may be to present white shame, this shame is not correctly represented as a painting of a dead Black boy by a white artist.” Lorena Muñoz-Alonso, “Dana Schutz’s Painting of Emmett Till at Whitney Biennial Sparks Protest” Artnet, March 21, 2017. ) This case is very important because it revealed a certain shift. Even a few years before, Schutz’s painting would have been considered as a gesture of solidarity with the Black Life Matters movement or the fight of the African-American community in the US, but instead it became completely subverted. So there are limits to solidarity and to essentializing. In regards to Suzana’s question, how to be in solidarity with others, when others sometimes deny your proximity, your right to show solidarity.

Like in the case of my recent correspondence with Nikita Kadan (https://syg.ma/@dmitry-vilensky/letter-to-nikita), the question occurred: what your words can mean and if they can save lives. It required a certain moralist approach to these issues, which we can’t ignore. You can’t simply say, I’m with Black people or I’m with Palestinians. What did you do for them?

Gregory Sholette (post-discussion):

Thank you all, I think that we certainly did not take anything for granted as is often the case when “loaded” words like “solidarity” are spoken in earnest and even for the best of reasons. At the same time, I also came away with the sense that solidarity is not a concept to simply abandon either. I will be thinking about our digital communion a lot, and I also wonder about the link between solidarity and sacrifice, especially during the coming winter months across Western Europe and the “Former East.”

This article is part of the Special Issue on Art and Solidarity. You can read the other articles included in the issue: