Revolutionary Romances: Into the Cold – Alternative Artistic Trajectories into (Post-) Communist Europe

On October 13, 2022, the Albertinum at the Dresden State Art Collections hosted an international conference entitled “Revolutionary Romances: Into the Cold – Alternative Artistic Trajectories into (Post-)Communist Europe.” The conference sought to question the simplistic East-to-West “defection” narrative of the post-war art worlds, and to explore the multiple alternative directions of travel by artists during the Cold War. Participants discussed why artists working in and beyond the West decided to enter the communist space, and considered the unexpected results of these subversive movements.

Following the conference, Christopher Williams-Wynn, a PhD candidate at Harvard University and one of the conference presenters, spoke with organizers Julia Tatiana Bailey (former Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the National Gallery Prague) and Kathleen Reinhardt (former Curator of Contemporary Art at the Albertinum, and current director of the Georg Kolbe Museum in Berlin). Here they share some insights into the impetus for the conference, its connection to their wider curatorial interests, and the multi-year research and exhibition project that the conference was a part of. They also provide an introduction to the recordings of conference presentations, which are now available on the Dresden State Art Collections website.

Christopher Williams-Wynn: How did your collaboration on Revolutionary Romances: Into the Cold conference come about?

Kathleen Reinhardt: Julia and I first started the conversation that led to this conference three years ago, in the context of a professional exchange between our respective museums, the National Gallery Prague (NGP) and the Dresden State Art Collections (SKD). We quickly discovered a shared research interest in challenging the flattening, homogenizing view of art in Central-East Europe, which we were both keenly aware of from our experiences of working on this subject matter both within the region and in institutions and contexts that were viewing it from afar. With the opportunity to host the conference and connect it to the Revolutionary Romances research project I initiated at the Albertinum in 2020, we decided to significantly expand our circle of co-conspirators. We chose to do this by bringing together examples of artists from Western contexts who chose to enter into contexts of socialist and recent post-socialist countries in Europe and elsewhere, as well as scholars looking at the art and the institutional frameworks aimed at facilitating exchange during the state-socialist era. We sought to broaden these first steps through a program that carefully considered the many artistic, institutional, and political entanglements in the Cold War art worlds. In particular, we aimed to foreground art historical accounts that worked in multiple, often contradictory, and fragmented directions stemming from transmodern contact and decentralized exchange.

Julia Tatiana Bailey: When Kathleen and I first met, back in Autumn 2019, I was in residence at the SKD learning more about the museum’s implementation of new approaches towards the contested art history of the GDR – particularly in terms of the museum’s collections and display practices. The visit was intended to inform my work at the NGP, where I was likewise seeking to encourage more critically engaged and research-based approaches to the art produced and acquired in Czechoslovakia during the four decades of Communist rule after the coup of 1948.

To prepare for my time in Dresden, I had read Kathleen’s article, “Can the Artists Help Survive? – New Approaches to Art of the GDR, Looking Back while Moving Forward.”(Kathleen Reinhardt, “Can the Artists Help Survive?—New Approaches to Art of the GDR, Looking Back while Moving Forward,” Mezosfera, no. 6 (January 2019), http://mezosfera.org/can-the-artists-help-survive-new-approaches-to-art-of-the-gdr-looking-back-while-moving-forward/) I recognized our shared interest in questioning the continuation of problematic art historical narratives that had developed out of Cold War era rhetoric and the “history written by the victors” (to paraphrase my compatriot Winston Churchill) after the fall of the Berlin Wall. So Kathleen and I were already debating whether to develop our conversations into a conference or a publication when the Art in Translation online journal at the University of Edinburgh approached me regarding a series of workshops supported by the Terra Foundation of American Art, and we decided to join forces.

CWW: What had brought you both to curate in those cities and what challenges did you find – both Kathleen moving from West to East Germany, and Julia moving from West to Central-East Europe?

KR: I moved from Berlin to Dresden, from a city still marked by its position on the fault line of the Cold War and which over the past 30 years has turned into a key node of the global contemporary art world and what is today perhaps the most cosmopolitan place in Germany. In Dresden, I reentered a former-Eastern context for the first time professionally. I was quite overwhelmed at first. With a scholarly background in African American art and Black Studies I confronted an institution still structured around a very German narrative of art history. But, I was quickly fascinated by how a particular social history of art was being told through figuration. Before its disappearance during the NS regime, Gustave Courbet’s The Stone Breakers (1849) was a central piece of the Gemäldegalerie collection. From there I embarked on a journey to read the collection, and understand its post-World War Two development with its inclusions and omissions, and the art historical narrative that was constructed through realism.

My other entry point was my previous study of Black Marxism. I arrived during a time when Pegida (an anti-Islamic, far-right political movement) was strong, dominating local public discourse, and the extremist right-wing party was on the rise, particularly in East Germany, which promptly appropriated disputes on East vs. West German art to manufacture fully-fledged campaigns fuelled by East German anger and frustration. The art history of the GDR was firmly in the hands of protagonists who had, since the 1990s, been stressing strong divisions between official and unofficial scenes, and who at times were irritated by the “new” decolonial discourses entering the field, despite the history of anti-colonial and related positions in “official” art histories throughout the existence of the GDR. And I think it is exactly here where we today need to look closer, in order to mine these gray zones of multiple contrasting but parallel realities.

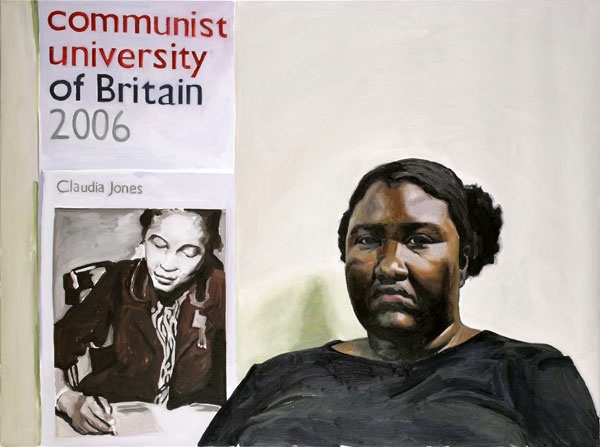

Yevgeniy Fiks, Portrait of Sheltreese McCoy, from the series Communist Party USA, 2007. Oil on canvas, 36 x 48 in. Courtesy of Fondation Francès

JTB: A year before my curatorial residency in Dresden, I had relocated to Prague from London, where at Tate Modern I’d managed acquisitions of art that originated in countries extending geographically from Central-East Europe across the former Soviet republics. Working on the art of “the East” while based in “the West” I became uncomfortably aware of the hegemony of the Western gaze in the creation and dissemination of art histories of countries formerly in the Eastern Bloc. This awareness inspired me to make my own move “into the cold,” in order to rediscover those art histories from the inside out. Since being in Central-East Europe, I have also observed how the East internalizes the Western gaze, often apparently to win approval from the Western art world that helps to secure financial benefits. Rather than reinforcing that gaze, I feel a responsibility to ensure the art historical and curatorial perspectives originating from this region have greater recognition internationally and are accepted on their own terms.

From my new viewpoint, I have also become keenly aware of how the old restraints of socialist regimes are being replaced by fresh constraints. The region’s self-image is being forged through efforts at distancing and reclamation, such as the collective amnesia, myth-making, and cathartic escape that Polish art historian Andrzej Szczerski has reflected on in detail.(Andrzej Szczerski, Transformation (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019) As I see it, the processes of forgetting a “communism that never happened” (as Szczerski puts it, referencing a provocative work by Romanian artist Ciprian Mureşan) have affected art history in postsocialist countries as much as art-making. And by the time our conference took place, the Russian invasion of Ukraine had increased the urgency of reassessing the disputed history of the Cold War both critically and honestly. As we have seen recently, from East Germany to Russia, collective amnesia risks leaving the field clear for forces that seek to co-opt and rewrite that history in the interests of an extremist agenda, which may have devastating consequences.

Jasmina Cibic, Tear Down and Rebuild, 2015. Video still, single channel HD video, 15 min 28 sec, stereo. Courtesy of the artist

CWW: All the presenters at the conference, including the contributing artists, drew upon primary sources and archival research. What was it important to foreground that type of research?

JTB: As the conference presentations make clear, working with archival materials regularly provides a challenge to what we think we know. It helps one to glimpse around the edges of the ideological blinkers that our contemporary world forces onto us, and it is always a stimulating wake-up call to be reminded that the course of history isn’t necessarily forward-moving. When one goes back to the primary sources, it soon becomes clear that the story has never been as black and white as we have often come to see it with our retrospective eyes. Art history, whether we have acknowledged it or not, has always been made up of many layers of gray, aside from a rainbow of other colors, including black, brown, red, yellow, pink, and purple. And here I am intentionally calling attention to the structural inequalities of class, race, colonization, gender, sexuality, and religious and political beliefs that have traditionally marked the borders of the art history that has been published and otherwise received institutional support.

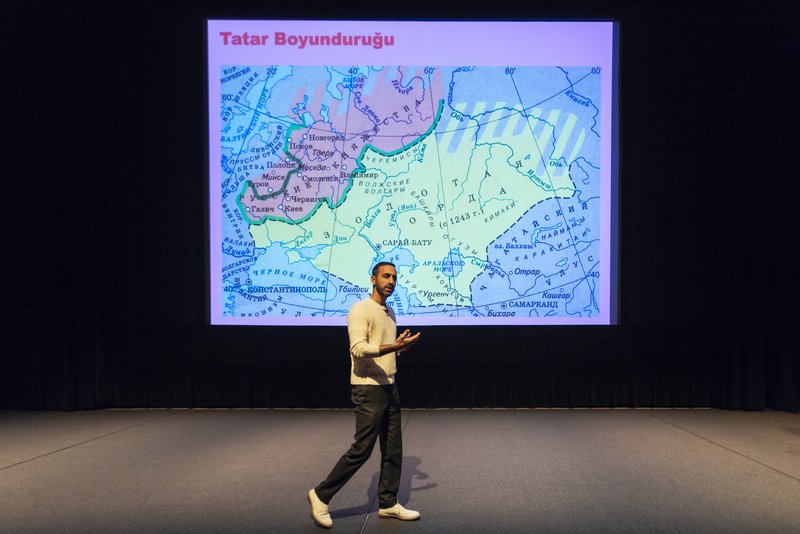

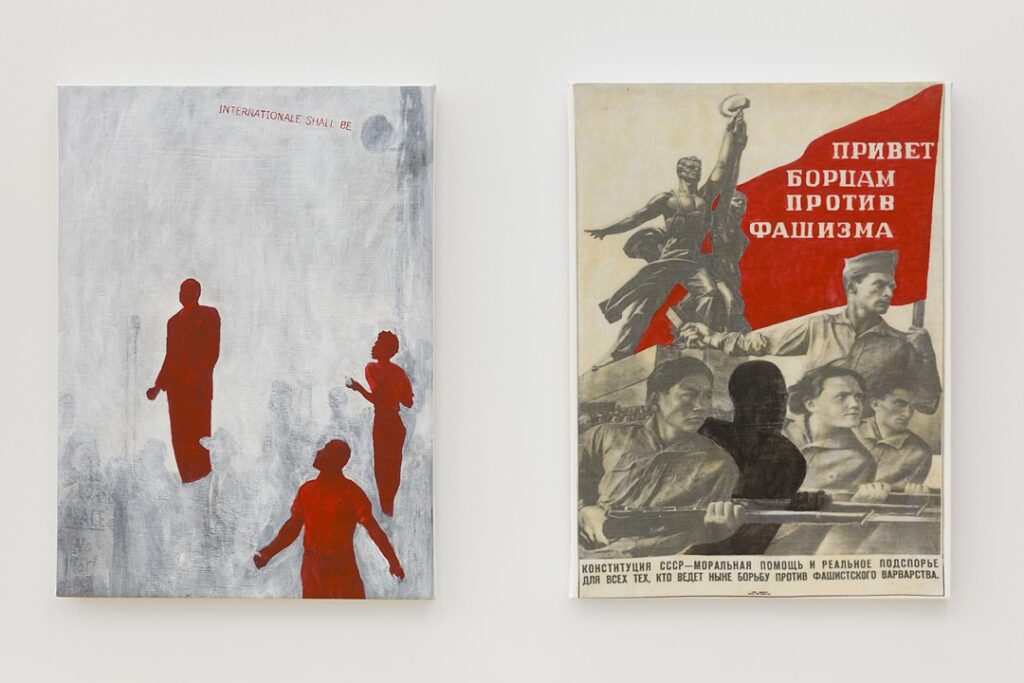

Kathleen and I actively intended to delve into more of these art histories during the “Revolutionary Romances: Into the Cold” conference. This concern was already evident in the first session of the day “Border Crossings,” which included Gaelle Prodhon’s triangulation of photographic strategies in revolutionary Algeria, France, and the GDR in the 1950s and 1960s; your [Christopher Williams-Wynn’s] exploration of the Mail Art encounters reaching between Eastern Europe and South America, and the works of Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt and Horacio Zabala; while Jérôme Bazin revealed, for instance, Mexican-inspired mural paintings in Bulgaria via his reading of works of the artist Olga Costa; and Mary Ikoniadou explored how the “transnational” refugee status of Greek artist Nikos Manoussis enabled him to cross both aesthetic and cultural-political borders. During the conference it was also a huge privilege to provide a platform for the important work of artists Jasmina Cibic, Yevgeniy Fiks, and Slavs and Tatars, all of whom conduct deep primary-source research to inform their artistic practices and are broadening and redefining art and art history as they do so. You can watch their artistic interventions at the conference also on the SKD website.

Slavs and Tatars, Red-Black Thread, 2018-present. Lecture-performance. The Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. Photo: The Walker Art Center Minneapolis, Bobby Rogers

KR: It was particularly important to show that this process of reassessment is not limited to art historians, but that contemporary artists with research-focused practices have already been looking at this for years. All come to very different conclusions, suggest different microhistories that embed larger questions, and variously recontextualize the aesthetics of the Cold War worlds. Their speculative efforts speak directly to our current visual and social longings, as in the case of Jasmina Cibic, for example. Therefore, the museum is an important meeting point, because art histories, exhibition cultures, and artistic practices past and present can coalesce for the visitors to enjoy, re-read, and eventually rethink. A look at configurations of interweaving, which the contributors of the conference applied throughout, rejects an all-encompassing approach, but rather proposes a transcultural art history as described by Monica Juneja, which demands that we work towards “a more precise and differentiated conceptual apparatus to plausibly describe and grasp the specificity and dynamics of global relationships.”(Monica Juneja, ““A very civil idea …”: Art History, Transculturation, and World-Making—With and Beyond the Nation,” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 81, no. 4 (2018): 469)

CWW: In the spirit of these connections, can you tell us more about the links between the conference and the Art in Translation journal, as well as its role as part of the aforementioned exhibition and research project Revolutionary Romances. Transcultural Art Histories in the GDR?(See the project website: https://albertinum.skd.museum/en/ausstellungen/revolutionary-romances/prolog)

JTB: Building on the work of the Art in Translation journal, the two volumes of the Hot Art, Cold War anthology published by Routledge in 2020 provide new English-language translations of primary sources that reveal European responses to the art of the United States between 1945 and 1990: one volume dealing with Western and North European perspectives, and the other with those from Southern and Eastern Europe.(Hot Art, Cold War—Western and Northern European Writing on American Art 1945–1990, eds. Claudia Hopkins and Iain Boyd Whyte (London: Routledge, 2020); Hot Art, Cold War—Southern and Eastern European Writing on American Art 1945–1990, eds. Claudia Hopkins and Iain Boyd Whyte (London: Routledge, 2020) When trying to recommend texts for translation or while writing my introductory essay for the section on the USSR, the focus on primary sources meant that I found myself, long after the fall of the wall, still heavily constrained by the strict, centralized controls of the Soviet-era channels for the dissemination of art history and criticism.(This experience led me to investigate the existence of unofficial Soviet art historical texts on the topic, away from the official narrative that passed the censor, leading to the article Julia Tatiana Bailey, “Moscow Conceptualism and the (Mis)Translation of American Art,” Art in Translation 14, no. 2 (2022): 108–41)

In response to this challenge, I came to focus rather on exploring what other “versions” of US art existed in the Soviet Union – prioritizing the “Eastern gaze,” as it were – outside the context of the West’s own Cold War-inflected controls over its domestic art history. It was this sort of thinking that planted the seed for the conference, and you can see it reflected in the second session of the conference, “Middle Grounds.” In their presentations, both Agnieszka Pindera and Maria Anna Rogucka focused on the reception of US art in communist Poland, which, as well as revealing a more porous Iron Curtain than is often acknowledged, demonstrates how important this Eastern gaze – both at that time and in today’s art history – can be for challenging and reinvigorating our understanding of the art of the West. And in the same session, through her focus on the Intergrafik 65 exhibition in East Berlin, Sophie Thorak further demonstrated how sites of display in the Eastern Bloc could provide a platform for alternative canons of international art that can inspire us all to think more expansively about shared values between artists working in different cultural and political contexts.

KR: We also incorporated what would become the Revolutionary Romances: Into the Cold conference into the Albertinum’s multi-year and multi-platform research and exhibition project Revolutionary Romances. Transcultural Art Histories in the GDR, whose starting point is the entangled art histories of the socialist worlds read through the Dresden collections. The multiple, unexplored connections between the GDR and communist countries of what is today termed the Global South were cultivated by exchange programs and institutional exhibition and collecting practices that were facilitated and perpetuated by the GDR’s politicizing official art system. Its numerous artistic and institutional linkages to Mozambique, Angola, Ethiopia, Vietnam, China, Chile, Nicaragua, Cuba, or the “other America” as they manifest in Dresden are the focus of the inquiries of Revolutionary Romances. Transcultural Art Histories in the GDR. Socialist art institutions in the GDR were composed of fragmented relations between official and non-official cultural fields, as were its internationalist relations. This double fragmentation, which conditioned and shaped the traversal global connections and how local art scenes functioned, are fundamental to the development of this project and the conference. In June 2022, the Albertinum teamed up with Kerstin Schankweiler at Technical University Dresden to host the three-day symposium The Global GDR – A Transcultural History of Art (1949–1990), which focused exclusively on the relations from and to the GDR. With the Revolutionary Romances: Into the Cold conference we were able to widen this substantially to include practices and particularities across the Bloc and their respective approaches.(See conference report and recordings: https://voices.skd.museum/en/voices-mag/the-global-gdr-a-transcultural-history-of-art-1949-1990)

Revolutionary Romances. Transcultural Art Histories in the GDR – Prologue, installation view, 2022. Albertinum Dresden. Photo: SKD, Klemens Renner

CWW: A dominant narrative of the Cold War focuses on unidirectional movements – whether of people, objects, or texts – from East to West. This focus, arguably a symptom of a “Western gaze,” obscures a host of other ways of approaching patters of movement during the period. How did you approach this trope, and what is at stake in its re-evaluation?

JTB: With the Revolutionary Romances: Into the Cold conference we were particularly seeking to disrupt the associated, loaded terminology of defection that is so closely entwined with Cold War propaganda, and one way to do that was to switch the focus 180 degrees by looking at the directly alternative direction of travel: from West to East. While the conference continued to foreground the idea of the East/West binary, I’m aware of the problematic nature and sometimes illegitimacy of these terms and their relationship to each other. I am consistently trying to destabilize the insistence on the bipolar viewpoint that was central to Cold War thinking and that still pervades art historical assessment of the period, and my exploration of the slippages in this binary opposition is in the interests of deconstructing rather than sustaining it.

One way of doing this is to focus on other power structures operating in this field, such as those of race, which cuts across the binary and was the focus of the third session of the conference, “Other Meeting Points.” Kathleen and I gave a presentation on Black US artists in the GDR and Soviet Union – including Oliver Wendell Harrington, Charles White, and Margaret Burroughs –before Jessica Horton continued with a fascinating exploration of the 1972 visit to Romania by Luiseño artist Fritz Scholder. The closing lecture performance of Slavs and Tatars, Red-Black Thread explored the construction of Black identity not from the traditional Anglophone and Francophone worlds of the Atlantic but rather from the Russophone idiom of imperial Russia and the Soviet Union. All of us discussed these sometime official, sometime unofficial entries into Communist Europe by racialized US artists in relation to contemporaneous campaigns for civil rights within the United States, demonstrating how states of belonging and Otherness can swiftly alter or even co-exist according to different contexts, which further exposes the manipulative nature of binary concepts.

Yevgeniy Fiks, The Wayland Rudd Collection (installation view) featuring Internationale Shall Be (2014, left) and Constitution of the USSR (2014, right) by Dread Scott, 2014. Winkleman Gallery, New York. Photo: Etienne Frossard. Courtesy of the artists

KR: The practical implementation of a global art history introduced some decades ago provokes a flattened reading of positions from socialist Eastern Europe or previously under-recognized BIPOC positions. In order to qualify for entry into a “canon under correction,” the narratives and labels that are attached to these art practices from Eastern Europe often signal, on the one hand, marginalization, and, on the other, dissidence. This establishes a moral high ground for these practices that can only serve as a corrective to the realities of many art institutions of the former West if they contain narratives of suffering. Only then are access, new spaces of scholarship, and museum display bestowed upon them. However, this updated albeit Western-centric labeling results in further Othering. What needs to be centered instead is how artists actively sought allyship and claimed agency through other infrastructures, such as the different modernities explored through practices of transcultural exchange.

To give more tangible examples I’ll briefly introduce you to the different platforms and networks of exchange feeding into Revolutionary Romances. Prologue – a research exhibition I organized earlier in 2022 together with my co-curator Mathias Wagner. This prologue, showed a first small selection of artworks from and about Cuba, Chile, and Vietnam. We further showed works by the contemporary artists Emeka Ogboh, Laura Horelli, Sung Tieu, and Angela Ferreira who proposed different contemporary views on our present of the condition of the “post” – a liminal stage of a not-yet while deconstructing socialist dreams worlds. For the digital program on the SKD’s online channel “voices” we’re inviting curators from countries that had political and cultural exchange with the GDR to present contemporary perspectives of other post-socialist environments through film programs, and Arlette Quỳnh-Anh Trần and Maria Berrios already put together fascinating screenings.

Revolutionary Romances. Transcultural Art Histories in the GDR – Prologue, installation view, 2022. Albertinum Dresden. Photo: SKD, Klemens Renner

CWW: To end – reflecting on the conference, and given these re-evaluations of culture in the Cold War, what kind of changes do you envisage for curatorial practice? Do you anticipate, for example, shifts in the types of objects included in the exhibition, as well as changes of their physical layouts and discursive frameworks?

KR: One method in contemporary curating dedicated to these matters has been to tell small stories to erode the big story. What is urgent here is that we radically reassess the social functions of art within its respective periods and environments. Thus, art must be treated in light of the different reference systems that these practices created, the constantly shifting gray zones they operated within, and the decentralization, and fragmentation, of the respective ideologies they followed, alongside the infrastructures that facilitated their contact. And because the presentations of these materials often need quite extensive and sensitive contextualization, especially when it comes to the continuities of racializations and racism, curating needs to be mindful to still center artists and their artworks, and not let it tip over into exhibiting the research and history around it only with the art as some sort of sideshow. I think this is the challenge here, and mindful curating creates spaces for both the concentrated aesthetic reception of artworks that deviate from known canons, as well as the possibility for the viewer to go deeper.

Jasmina Cibic, NADA: Act II, 2017. Film still. Single channel HD video, 13 min. Co-commissioned by European Capital of Culture Aarhus 2017, BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art Gateshead and supported by Arts Council England, Northern Film School at Leeds Beckett University and Waddington Studios London. Courtesy of the artist

JTB: In terms of curating collections, I learnt a great deal while working to re-present the post-1938 Czech state art collection in Prague, a large percentage of which was acquired in the 1950s and 1960s and made in support of the communist regime. It requires great sensitivity and a collaborative approach to start to discuss and display in a critical way artworks that have become symbols of national shame and trauma, and it is understandable why, across Central-East Europe, there has been a tendency to avoid this art. But I am pleased to find my colleagues in Prague and wider Central-East Europe increasingly responsive to new approaches and committed to presenting more complicated and, ultimately, more authentic interpretations of the art originating and being collected here. And the very positive response to the Revolutionary Romances: Into the Cold conference reconfirms this wider trend in art history. I do not suggest that Socialist Realism and other forms of state-imposed propaganda art should be shown out of context. This is not about rehabilitation or ignoring the abuses that it supported. But I believe this art is part of who we were and still are as a society, it is worth preserving and seeking to understand, and it has value – even if its main value now is to mark a moment in history we have moved past and should be vigilant not to return to.