“Subversive Practices: Art under Conditions of Political Repression. 1960s -1980s / South America / Europe” in Stuttgart (Exhib. Review)

Subversive Practices: Art under Conditions of Political Repression. 60s – 80s / South America / Europe, Württembergischer Kunstverein Stuttgart. May 30 – August 2, 2009

This summer, the exhibition Subversive Practices: Art under Conditions of Political Repression 60s–80s / South America / Europe was presented at the Kunstverein in Stuttgart. As the organizers Iris Dressler and Hans D. Chris state, the exhibition describes “a multidimensional cartography” in which the many faceted contours of work spanning periods of time and geographical categories appear anew, often, from beyond the margins of skewed art discourses.

Subversive Practices assembled practices and theoretical positions within a trajectory joining countries of Europe with counterparts from South America. Its critical mass was achieved not simply by the quantity of works drawn from the last four decades of the twentieth century or the Kunstverein’s spatial dimensions but rather because of an ability to enjoin artistic work, indeed endeavors and obsessions, challenging the canonical assumptions and definitions that often view the art world with a decidedly Anglo-American bias.

Thirteen curators participated in a project that contained more than 300 works by nearly eighty artistsfrom nine countries (two of which no longer exist). The intent of this overview is not to highlight one work versus another, which would negate the exhibition’s importance, but also to challenge the constraints of those discourses marked by an art criticism often nestled safely within borders drawn by the exigencies of art markets.

According to Dressler and Chris, these are works in which, “body, language, and public space represent the pivotal instruments, of resistance, symbolic and performative in equal measure.” This covers a broad terrain, not simply the landscape of Soviet-style stagnated socialism with its authoritarian variants, but social environments controlled by forms of repression in which the most minute social deviations can trigger confrontations with the police or military.

And thus, what could be seen were the articulations and topographical outlines of the ‘power relations’ that appeared under various forms of authoritarianism and which, as Foucault states, “attack everything which separates the individual, breaks his links with others, splits up community life, forces the individual back on himself, and ties him to his own identity in a constraining way.” Consequently, ‘resistance’ here embodies various forms of conceptual strategies to establish or re-confirm links and maintain a sense of identity amidst a societal fog that blurs both individual desire and collective life.

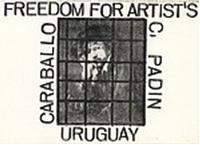

The Brazilian curator Cristina Freire tells us that in “those days the postal service was the privileged medium of communication in this extended circuit, unaware of the art market and the concerns of the hegemonic art centres.” This circuit linked artists from Brazil with those in Eastern Europe who “were in search of strategies with which to get around the censorship imposed by a dictatorial regime.” The strategy extended beyond the Brazil-Eastern Europe postal circuit but included public interventions, discrete conceptual actions and other ephemeral activities. Often the existence of a particular work or project was maintained only through photographs or other forms of documentation.

Artur Barrio’s installations and performances in Rio de Janeiro took place in public spaces and then slowly disappeared. Similarly, in Hungary, Gyula Pauer’s 1970 project Protest Sign Forest pre-figures the type of public interventions that would appear later in the West. In this example of Pauer’s completed works, covering an area of about 400 sqm, it lasted for barely a day and was eradicated immediately before anyone could view the work. The sole record of its existence are Pauer’s photographs.

Begun in 1976 during the twilight of the Brezhnev years in the Soviet Union, performances by the Russian group Collective Actions, employed a comparable strategy in order to explore “an alternative space for communication in Russian-Soviet culture during late communism” according to Sabine Hänsgen, this section’s curator. Like INDIGO in Hungary, Collective Action has endured and continues to transform its original concepts in order “to comprehend contemporary processes of globalization.”

Begun in 1976 during the twilight of the Brezhnev years in the Soviet Union, performances by the Russian group Collective Actions, employed a comparable strategy in order to explore “an alternative space for communication in Russian-Soviet culture during late communism” according to Sabine Hänsgen, this section’s curator. Like INDIGO in Hungary, Collective Action has endured and continues to transform its original concepts in order “to comprehend contemporary processes of globalization.”

Related tactics appeared in the German Democratic Republic where artists, facing serious repercussions, used their cleverness, as described by Anne Thurmann-Jajes, “to continue their artistic activities, indeed with very enigmatic, astute, and ironic allusions to the system.” In these instances, discretely organized raves or happenings were not simply performances but reaffirming events. Equally, the appropriation of abandoned or empty public spaces and windows created exhibition venues outside the normal channels.

Related tactics appeared in the German Democratic Republic where artists, facing serious repercussions, used their cleverness, as described by Anne Thurmann-Jajes, “to continue their artistic activities, indeed with very enigmatic, astute, and ironic allusions to the system.” In these instances, discretely organized raves or happenings were not simply performances but reaffirming events. Equally, the appropriation of abandoned or empty public spaces and windows created exhibition venues outside the normal channels.

A daring example of this circumventing of official channels was the “First Leipzig Autumn Salon” in the summer 1984. In his record of the event, Lutz Damm recounts how a group of painters, sculptors and filmmakers “employed courageous, partisan tactics to occupy a trade-fair building at the heart of Leipzig’s inner city, where they produced and curated their own group exhibition in an area of more than 1000 qm.”

A daring example of this circumventing of official channels was the “First Leipzig Autumn Salon” in the summer 1984. In his record of the event, Lutz Damm recounts how a group of painters, sculptors and filmmakers “employed courageous, partisan tactics to occupy a trade-fair building at the heart of Leipzig’s inner city, where they produced and curated their own group exhibition in an area of more than 1000 qm.”

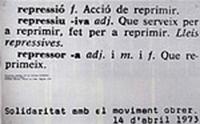

Beyond central and eastern Europe, in Catalonia, during the closing years of the Franco dictatorship, the appearance of associations like Grup de Trebal, with its nineteen members, signaled a surfacing of repressed cultural identities and a “moving away from conventional artistic practices and joining a critical current where art had to fulfill a social function.” Alternative exhibition spaces such as COAC (Association of Architects of Catalonia) and Sala Vinçon appeared and became sites both for presentations and meetings. In spite of the state of emergency declared in 1975, artists from a broad range of disciplines, including Pere Portabella and Antoni Muntadas, were able to circumvent constraints and explores new vocabularies. Thus, in a highly regulated cultural atmosphere, new public spheres on the boundaries of the permissible fostered activities that came to maturity at later dates.

This was certainly the case in Hungary. Annamária Sz?ke and Miklós Peternák, the Hungarian curators, recall how in the late 1960’s, “in opposition to the official ‘first’ public sphere of artists, another ‘second public sphere’ began to take shape.” This type of stratification, which manifested itself in various forms in all the countries represented in the exhibition, typifies the conflicting realms of an ‘official’ culture and its designated outlets and a more socially embedded vein of cultural activity emerges linked to previous currents but also to present realities and aspirations.

Working within this second sphere, the INDIGO group, emanating from from classes led by Miklós Erdély, challenged not only pedagogical boundaries but also the nature of an interdisciplinary praxis. INDIGO’s examination of the social responsibility of the artist reflects a multi-faceted thread that appears throughout the exhibition. A thread not coloured by one ideological strand but rather imbued the diverse challenges of each society.

Working within this second sphere, the INDIGO group, emanating from from classes led by Miklós Erdély, challenged not only pedagogical boundaries but also the nature of an interdisciplinary praxis. INDIGO’s examination of the social responsibility of the artist reflects a multi-faceted thread that appears throughout the exhibition. A thread not coloured by one ideological strand but rather imbued the diverse challenges of each society.

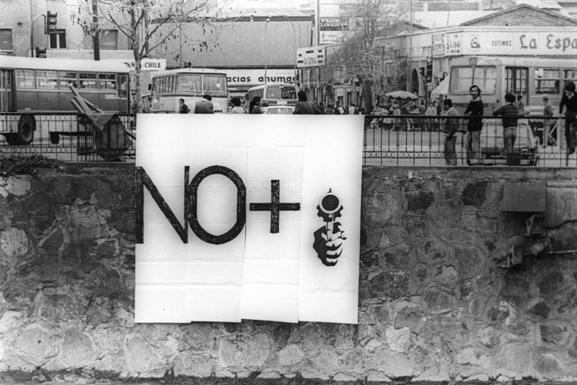

The complexity of situations in which cultural praxis is driven into subterranean channels appears in the Chilean section the curators Ramón Castillo and Paulina Vara recount how “the language of art was turned into a silent—silenced—battlefield.” In 1979, five years after the military coup, CADA – Colectivo de Acciones de Arte began initiating actions which addressed human necessities and gave voice to ‘silenced’ artists. Their project In order not to die of hunger in art consisted of half-litre bags of milk which they distributed in a barrio in Sanitago de Chile and then used the recycled bags in other projects. They also initiated the slogan NO+ which appeared on walls throughout the city. The slogan became a sign of resistance to the dictatorship.

The complexity of situations in which cultural praxis is driven into subterranean channels appears in the Chilean section the curators Ramón Castillo and Paulina Vara recount how “the language of art was turned into a silent—silenced—battlefield.” In 1979, five years after the military coup, CADA – Colectivo de Acciones de Arte began initiating actions which addressed human necessities and gave voice to ‘silenced’ artists. Their project In order not to die of hunger in art consisted of half-litre bags of milk which they distributed in a barrio in Sanitago de Chile and then used the recycled bags in other projects. They also initiated the slogan NO+ which appeared on walls throughout the city. The slogan became a sign of resistance to the dictatorship.

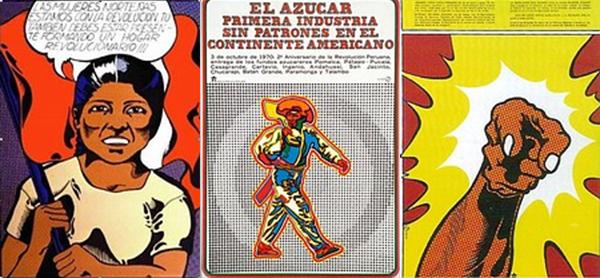

Analogously, in Peru the eight members of Taller E.P.S. Huayco, a group which lasted from 1980–1982, utilized ‘found materials’ and well known images. In the piece, Art on the Way, they copied a popular fast-food image and used it to form a carpet composed of painted resembling the dots in Pop Art paintings. Following this project, they produced the likeness of a Sarita Colonia, an unofficial saint adored by many on the margins of Peruvian society. The large image was constructed on a hillside adjacent to the well traveled Pan-American Highway.

Analogously, in Peru the eight members of Taller E.P.S. Huayco, a group which lasted from 1980–1982, utilized ‘found materials’ and well known images. In the piece, Art on the Way, they copied a popular fast-food image and used it to form a carpet composed of painted resembling the dots in Pop Art paintings. Following this project, they produced the likeness of a Sarita Colonia, an unofficial saint adored by many on the margins of Peruvian society. The large image was constructed on a hillside adjacent to the well traveled Pan-American Highway.

In contrast with the ensembles or collectives whose innovative activities maintained a resilient unofficial culture, strong individual voices persisted in defining forms of expression to negate the authorized vocabularies of the official culture. From exile, the Chilean, Guillermo Deisler used the vehicle of mail art to maintain contact with his homeland and at home Carlos Leppe used his own body as a metaphor for the repressed nation. In Peru, Employing a different strategy, and also with the support of the military government, Jesús Ruiz Durand transformed North American pop styles to promote the new industrial and agrarian policies. Francesco Mariotti’s intervention Artificial Wash Basin for Special Use Intervention was intended for installation in a restroom at the Banco Continental gallery in Lima in 1975. The piece never appeared and was destroyed before it could be seen by the public. An updated version of the piece was shown in the Stuttgart exhibition.

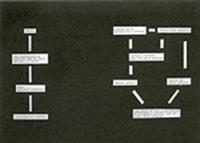

In Brazil, Peru and Romania, the artist’s body became a site of investigation as well as a living canvas. Using ‘self-portrait’ and ‘identity’ documents as tropes, Teresa Burga created an installation where Face Report, Heart Report, Blood Report became the headings for the display of related data which she collected over the course of a single day. In Letícia Parente’s eleven minute film, the artist sews the words “Made in Brazil” on to the sole of her foot. Seen in close-up, the branding becomes both self-referential to the artist’s status and the broader social realities.

In Brazil, Peru and Romania, the artist’s body became a site of investigation as well as a living canvas. Using ‘self-portrait’ and ‘identity’ documents as tropes, Teresa Burga created an installation where Face Report, Heart Report, Blood Report became the headings for the display of related data which she collected over the course of a single day. In Letícia Parente’s eleven minute film, the artist sews the words “Made in Brazil” on to the sole of her foot. Seen in close-up, the branding becomes both self-referential to the artist’s status and the broader social realities.

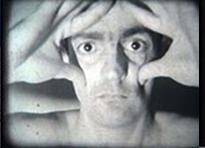

Not surprisingly, in environments with stringent cultural regulations, the body as the focal point of activity, appeared in Romania also, where “several artists tried to make up “survival” techniques [imbued with] ephemeral forms, at irony and social criticism.” Making use all possible sites inorder to, as Ileana Pintilie Teleaga says, to defy censorship.” A case in point is Ion Grigorescu whose “visual research” projects emanate from within the artist’s private space and self-confabulations. These filmed “post-happenings” both pre-figure and appear in parallel with other forms of performance art which were able to find semi-private or more public venues. As in much of the work in this exhibition, their existence is only corroborated by different forms of documentation which in many cases were integral to the work.

Not surprisingly, in environments with stringent cultural regulations, the body as the focal point of activity, appeared in Romania also, where “several artists tried to make up “survival” techniques [imbued with] ephemeral forms, at irony and social criticism.” Making use all possible sites inorder to, as Ileana Pintilie Teleaga says, to defy censorship.” A case in point is Ion Grigorescu whose “visual research” projects emanate from within the artist’s private space and self-confabulations. These filmed “post-happenings” both pre-figure and appear in parallel with other forms of performance art which were able to find semi-private or more public venues. As in much of the work in this exhibition, their existence is only corroborated by different forms of documentation which in many cases were integral to the work.

In this context, and the exhibition’s discursive frame, a subversive practice is not simply a transgressive or experimental work or act but rather an affront to authority and political power. Thus, as seen here, artistic expressions, like other exigencies of survival, are very much manifestationsof individual necessity, regardless of the political circumstances. Yet, whether brought to life by an individual or group, they are representations of the moment and refractions of the cultural forces with give that moment its spatial and temporal realities.

What is striking than is the manner in which these efforts eluded the traditional boundaries and drew upon interdisciplinary connections defined by members of a collaborative or by a vocabulary not restricted by an imposed formalism. Within this framework, conceptualism can be seen as a much broader methodology, a piece or project that is not grounded in its ‘conceptual thingness’ but rather emanates from within a conceptual orbit or field of activity that both crosses and utilizes multi-disciplinary lines evolving from its idea as well as the social and political realities within which it exists.

The exhibition thus reaffirms a truism perhaps: that even under the most regimented conditions and beyond the glosses of socialist realism or a neutralized and depoliticized ‘modernism’ that were the official palliatives other solid forms of cultural activity were always flowing beneath the surface and searching for their outlets.

In any event, what becomes apparent are the false terms, the one dimensional binaries, of the types of discourse promulgated by Lucy Lippard when she discusses an “activist art” which is different from or in opposition to “mainstream” art. In these types of formulaic descriptions, emanating from conditions in which cultural activity is contained within a framework of a highly developed art market, labels can only tell us which aisle we are entering or leaving. What is called for is a further exploration of the possibilities of various forms of expression which rupture an obtuse commodified formalism and which in a sense demystify the cultural forces of highly commodified advanced capitalist societies. What is perhaps symptomatic of this discourse, or rather its limitations, is that it omits, either from ignorance or lack of interest, the body of work which appear in this exhibition.