Problems in Transit: Performance in Romania

Politically, socially, and economically speaking, the collapse of communism has brought about a lot of changes to the countries of East-Central Europe. The demise of the communist system in Romania in 1989 exposed a political, social and economic crisis that had been hidden for decades. The consequences were dramatic: After more than twenty years of dictatorship – with the 1980s as the most oppressive period – the overthrow of the totalitarian system culminated in a coup d’état. Romanian society was shattered and traumatised to the core.

Beginning in 1990, for the first time in many years, Romanian performance artists came out of hiding and went public, soon to enjoy a great deal of popular success. If on the international scene performance art more or less exhausted itself during the 1960s and 70s, in Romania, performance art had only existed underground during that period. Only after 1989 could it begin to exert its influence. After a long period of utter isolation of public life, the Romanian public was only now beginning to open up to the experience of performance. In fact, performance became a way of communicating in a society whose members discovered the freedom of opinion by participating in anti-government street manifestations.

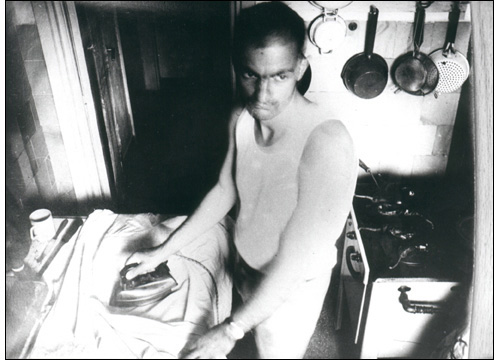

This is not to say that Romanian performance art of the 1990s looked just like its underground predecessor from the 1960s and 70s. There were considerable differences between performances during the ‘70s, the ‘80s, and the ‘90s. Ion Grigorescu, to name but one example, was preoccupied, in his early actions (1974-1978), with problems of composition and “visual mechanics as a partner in the performance”. Consequently, he staged his performances before a camera. The sources of Grigorescu’s first body actions (as well as his political performances) must be sought in his concern with the problem of “realism” and “reality”. Grigorescu combined painting and photography, producing photo montages that represented an ironic reaction to the ideological directives of Socialist realist aesthetics. At that time his actions were dedicated to the values of “real”, everyday life, and the way it influences art. In performances such as The Kitchen or Art in a Single Room (1976), Grigorescu presented himself in a small room filled with utilitarian objects and performed ordinary household activities. The Kitchen evolved around the idea that banal, ordinary reality is equivalent to a work of art. At the same time, the performance did not fail to show that reality in all its brutality.

In his small studio, Grigorescu staged a performance entitled In Prison (1978) in which the idea of captivity was expressed through the use of surveillance instruments such as a peep-hole and a tele-photolens. Grigorescu himself appeared in striped pyjamas, performing stretching exercises or swallowing bread crumbs. This was designed to simulate life in prison as well as the kind of intrusive, round-the-clock surveillance of private citizens the Romanian police was practising at the time. In the 1990s, Ion Grigorescu went public with a highly political installation that was very much in keeping with the politically charged atmosphere in the country at the time. The title of this work is suggestive of the collective desire for purification from an ambiguous, oppressive past: The Country Does not Belong to the Militia, the Securitate [=the former Romanian secret police], or the Communists (1991). The installation was on view in a public square in Timisoara as a symbol of freedom from communism, yet it also confronted Romanian society with a message of extreme ambiguity. Grigorescu’s subsequent public performances bore on the painful issues that were making headlines in Romania at the time. The fact that he staged these actions in the intimate atmosphere of his studio was of special importance. It was here that Grigorescu took on controversial political issues such as that of the former Romanian province of Bessarabia which had just proclaimed its independence from Russia, or the question of Romanian national identity.

At the beginning of the 1990s, performance became a kind of civic attitude for several Romanian artists who felt that they had to openly participate in the construction of a new society by publicly testifying to the truth. Constantin Flondor, who did most of his work in the 1960sand 70s, belonged to the first experimental performance group in Romania. He was a participant in a group performance that took place in Timisoara in 1991, entitled A State without a Title. Flondor’s contribution to this event was an installation entitled The Blind Man’s Sunday, a bitter account of the results of the first free elections organised in Romania after the collapse of communism. Flondor used apples as symbols of the voting process, painting some of them with black paint. Flondor’s public performance met with a violent response from the audience who did not take kindly to the artist’s critical attitude.

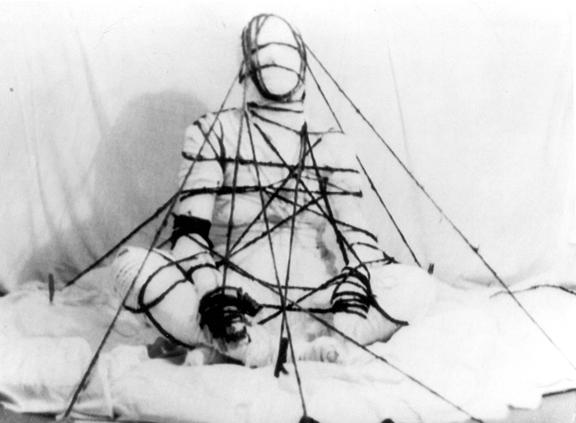

The experience of the transition from the loneliness of the artist’s studio, or even of his or her private apartment, to the public square was also reflected in performances by Amalia Perjovschi, a young artist whose artistic debut took place in 1989. For a while Perjovschi preferred her own apartment as a stage for her performances, because it provided her with the kind of confined, controlled context she was looking for. In 1988, she created a body action entitled The Test of Sleep, in which she covered her body with writing. She then took pictures of herself, posing before the camera as a motionless, passive surface, an attitude that symbolically connoted the lack of communication that was the numbing corollary of the Ceaucescu era. Another performance, Annulment (1989), which was also staged in Perjovschi’s apartment, was directed against the entire social and political context at the time. The artist let herself be tied up by her husband, Dan Perjovschi, the only person present except for the artist herself. In 1991,this time in Timisoara, Perjovschi created a street performance entitled The State without a Title as part of the group event that went under the same title. The performance reflected the general atmosphere of the time. Perjovschi carried on her back the burden of two large objects made from paper and cloth, giving the impression that she was doing penance. One of these objects was about as large as the artist herself and attached to her back. The other one was much longer and had to be dragged on the side-walk. Perjovschi wanted to find a symbolic way of conveying the idea of a double personality.

As the 1990s wore on, Romanian performance artists increasingly abandoned the street with their active spectator participation for more secluded professional spaces, such as galleries and museums. The “Zone” Performance Festival which was organised for the first time in Timisoara in 1993 offered the artists the possibility of performing in front of more sophisticated audiences. It was here that Lia Perjovschi created the performance I Fight for My Right of Being Different in which the artist treated a full-size stuffed doll to intermittent displays of love and aggression, suggesting the kind of oscillation between power, abuse, and passive conformity typical of a population that has not yet absorbed the civil liberties that come with democracy.

Alexandru Antik’s now-legendary performance The Dream Still Lingers dates from 1986. It was created for the Sibiu Youth Festival and took place in the cellar of a pharmacy museum, before an audience made up mostly of artists and art critics. The performance included the artist’s own neo-Dadaist texts which were recited in a loud voice before a background of bleeding animal intestines as symbols of brutal reality. Antik’s performance ended abruptly when plain clothes police stormed the stage, removed the films from the running cameras and told people to leave the room. Like Perjovschi, Antik preferred conventional spaces, such as a stage, to the street as a venue for his performances, which allowed him to isolate himself from the spectators. Like other Romanian performance artists, Antik regularly went through the motions of displaying public penance, suggesting his “purification” from Romania’s grizzly political past. (I might add here, though, that while Romanian artists were perhaps a bit excessive in their need to divest themselves in public of their own guilt, the country’s politicians have curiously never felt such a need). During a performance entitled Shedding the Skin (Timisoara, 1996), Antik ritually lifted an artificial layer of skin off his own body and fastened it with nails to the wall.

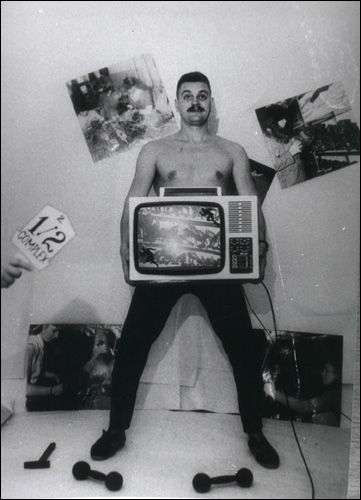

The social and political situation during the period 1985-89 was very tense. There was the terrible destruction of Bucharest’s historical center, the daily fight against political oppression, and there were the obligatory propaganda images during the two hours of State television a day. Teodor Graur chose this reality as his main source for inspiration for his performance work, usually staged in front of a handful of devoted friends. Graur began to explore grim Romanian reality during the late 1980s, choosing his own athletic body as the focus for his parodic, scornful reflections on the realities of Romanian life. The performance The Sports Center (1987), for example, pinpoints brutal, brainless virility as a sure means of social success, alluding to the modernist ideal of the “new-man”with its glaring mismatch between muscles and intelligence.

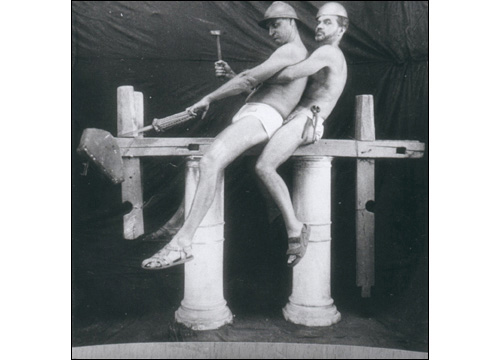

Another action, Remembrance of the Ship, was staged in the huge empty cargo-hold of a ship and dealt with the frantic desire to emigrate which filled all young Romanians under Ceaucescu to the point of obsession. After 1989, Graur continued his critique in the context of the new realities created by the post-Ceaucescu transition. Speaking to Europe (Timisoara, 1993) featured the artist locked up in a large cage in front of the audience, shouting frantically into a microphone (in English): “Hello, hello, can you hear me ?” The only answer he received were fragments of radio broadcasts which Graur found as he turned the knob of his radio receiver. In 1994-95, Graur and Olimpiu Bandalac formed the group “Euro-Artist”, which continued Graur’s social critique in the medium of photography, using a vernacular that included the icons of socialist realism (The Hero of the Carpathian Mountains, 1995).

The dilemmas facing performance artists during the transition from communism to post-communism were reflected, especially, in their evolving relationship with their changing audience, an audience that gradually came to include even minorities. A good example for this evolution are Gusztav Uto and Reka Konya who in their performances have variously investigated the politics of identity in relation to the Hungarian minority in Romania, a minority of which they are themselves members. Performance art, in Romania and elsewhere, attempts to establish a viable dialogue through the medium of the artist’s body.

The early performances by Dan Perjovschi, who began working as a performance artist in 1988, were developed in the same context of isolation and spiritual exile. Perjovschi is one of the few Romanian artists who have been able to build an international career for themselves without leaving the country. In Oradea, he created the performance The Tree which dealt with the fragile relationship between the artist and nature. In another performance, Red Apples, he covered the walls of his apartment with white paper to which he diligently committed stories related to his relationship with his wife, Lia Perjovschi. The voice of official propaganda, Perjovschi’s own tv set,was also “wrapped up” and then covered with the artist’s inscriptions. At the exhibition The State Without a Name (1990), Perjovschi decided toisolate himself both from the audience and from the other artists by movinginto the janitor’s office at the Timisoara Art Museum. As he had done before in his apartment, he began to cover the walls of this small room with paper, which he then proceeded to cover with inscriptions as part of an elaborate, three-day-long drawing performance. In the end, the white paper was almost completely covered with black ink. Drawing as a running commentary or a kind of diary is an important part of Perjovschi’s art. Initially, he was rather introspective as an artist, but after 1992-93 his interest began to shift more and more towards what was around him. His attitude towards performance changed in the process. Perjovschi’s work has become more conceptual, with a general tendency to withdraw the artist’s subjectivity behind the conceptual idea. At the 1993 Timisoara “Zone” Festival, Perjovschi performed what he termed an “anti-performance” which, unlike traditional performances, would last for a lifetime. The artist let himself be tattooed with the name “Romania”, as if in this way he wanted to rid himself of a stubborn obsession.