Performativity of the Private: The ambiguity of reenactment in Karol Radziszewski’s Kisieland

In his 1995 text Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, Jacques Derrida notes that “[e]ffective democratization can always be measured by this essential criterion: the participation in and access to the archive, its constitution, and its interpretation.”(Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, translated by Eric Prenowitz (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1998), p. 11.) The narratives of a communist country inevitably challenge this statement since its archive, whether understood literally or in a figurative sense as the Foucauldian “system of discursivity,” is heavily censored and inaccessible to most. In the context of now-democratic Poland, how are those once-archived and silenced narratives of homosexual community presented, and acknowledged? Is the archive now wide open, or does it still remain largely in the proverbial closet?

In 2009, the artist Karol Radziszewski initiated his work on Kisieland¸ the project exploring the work of Polish gay activist Ryszard Kisiel, and tracing the archival and social limitations of the Polish LGBTQ narratives. As of 2017, the ongoing project includes a thirty-minute 2012 film under the same title,(From here on, unless otherwise indicated, I will use the title Kisieland to refer to the thirty-minute film as opposed to the entirety of Radziszewski’s project.) introducing and subsequently re-appropriating slides of photo sessions between Kisiel and his friends; reproductions of pages of Kisiel’s zine Filo and an extensive interview with the activist in Radziszewski’s self-published DIK Fagazine: Before ’89 (2011). In 2016, Radziszewski, further drawing upon the narrative he has developed with Kisiel, prepared a new performative work called Ceremony, inspired by the character of “Indian Shamaness,” one of the personas Kisiel had invented during his photo sessions. Throughout the text, I analyze these works to explore Kisiel’s extensive, ever-evolving archive, its performative reappropriation by Radziszewski, and its meaning to LGBTQ narratives in the current sociopolitical conditions in Poland.

We ought to attempt to understand Kisieland in the social context of the reactions of a strongly Catholic, conservative Poland to gay narratives, and the apparent unpreparedness of the Polish audience to embrace, as Tomasz Basiuk notes, “the more candidly sexual aspects of identity claims, even in relatively tame and playful forms.”(Tomasz Basiuk, “Notes on Radziszewski’s Kisieland,” in Archive as Project, Krzysztof Pijarski, eds. (Warsaw: Archeologia Fotografii, 2011), p. 469.) Particularly in the light of the recent conservative shift in the country’s politics, culminating in the 2015 parliamentary and presidential elections, both won by representatives of the far-right party Law and Justice, the Polish public sphere has been progressively deprived of representation of any minoritarian discourses. The government’s position on abortion rights, LGBTQ rights, and the immigration and the Syrian refugee crises, has been that of dismissal, which has recently raised voices of concern from the United Nations and the European Council. In March 2017, representatives of the Coalition for Civil Partnership and Marriage Equality, having exhausted procedures available on the national level, filed an official complaint to the European Tribunal in Strasbourg in an attempt to gain recognition of civil partnerships in Poland.(Marta Walendzik “Breakthrough on the way to introduce civil partnerships? Homosexual couples file a lawsuit to the Tribunal in Strasbourg,” Newsweek Poland, March 2017. http://www.newsweek.pl/polska/spoleczenstwo/homoseksualne-pary-zaskarzyly-polske-do-trybunalu-w-strasburgu,artykuly,407947,1.html (Accessed April 20, 2017).)

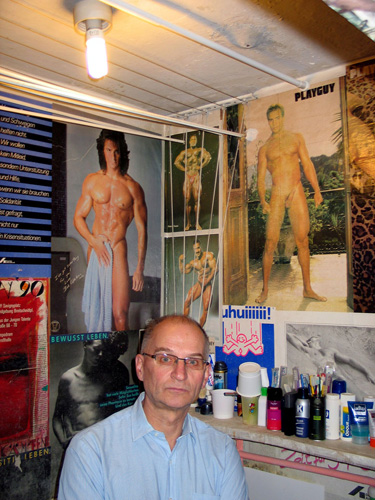

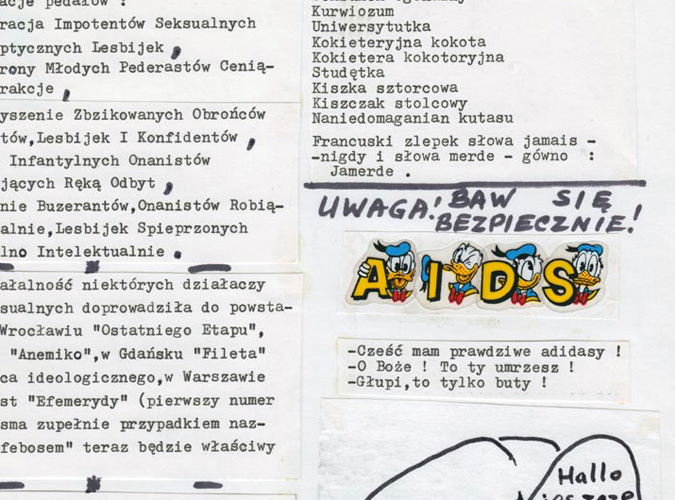

In Kisieland, Radziszewski visits Kisiel’s flat in Gdańsk, a seaside town in Poland, to discover that it houses countless newspapers, magazines, fliers, books, and other archival materials. The focus of the film is, however, Kisiel’s substantial slide collection, containing images of him and his friends posing naked, in drag, or in impromptu costumes, often in arranged, but still filled with natural charm, sexual scenes. In some images, the emotional bonds and erotic connections between those photographed are palpable, while others resemble Robert Mapplethorpe’s earlier works.(See Valerie Santagto, Jay Johnson Modeling Mapplethorpe-designed Jewelry, 1973.) Some of the photographs undertake the theme of AIDS activism, tackling it with humoristic exaggeration – as Kisiel told Radziszewski:

“[T]he AIDS epidemic was a traumatic event for our gay community… Lots, lots of people gave up sex… But with time…It’s difficult to stay serious when you’re surrounded by something constantly. Too many funerals, tragedies, death and sickness – I think people … become indifferent and start joking about it, just as a counterweight.”(Ryszard Kisiel, interview by Karol Radziszewski, Kisieland, film, 2012. Courtesy of Radziszewski.)

Kisieland introduces these photographs to the public for the very first time, leaving the boundary between the public and the private fractured but not unambiguously transgressed. The spontaneously arranged photo sessions were presumed as a private act and thus not meant for publication. This was partly because of the possibility of persecutions by the Polish communist government, and the risk of being charged with the distribution of pornography, but also because the authors had assumed that the themes such as erotic scenes between men, cross-dressing or HIV/AIDS would be of no interest to anyone outside of the closed and closeted gay community.(Kisiel, interview by Radziszewski, Kisieland.) The carefully prepared selection of slides used in Radziszewski’s film appears as an attempt to release such documentation from the closet calling for reaction from the public, but is not a simple gesture of revealing a private archive. Especially because a considerable part of the gay narratives of communist Poland – including the so-called Pink Files, the archive of “Operation Hyacinth” – remains uncovered, there does not seem to exist the social approval for uncovering such documents. This is due to, as Basiuk writes, “the difficulty of establishing with any degree of clarity the meaning of such records, testimonies and traces. … [W]hat may be missing are the conditions for their legibility in the public sphere.”(Basiuk, pp. 468-69.) Radziszewski is known for his interest in the archive as a point of access to the past that can be an impulse for influencing the future.(Eugenio Viola, “The Body as an Archive,” in Karol Radziszewski. The Prince and the Queens (exhibition catalogue), Eugenio Viola, eds. (Toru?: Centre of Contemporary Art Znaki Czasu, 2014), p. 27.) His work on Kisiel’s narrative might therefore be an opportunity to question the state of the current Polish LGBTQ communities not only in relation to the communist past of the country, but also to their own status within contemporary society. In this society, liberated as it is from the former oppressive political system and from official censorship, does the emancipation of homosexual identities follow or does it fall victim to self-censorship?

In reaction to “Operation Hyacinth” – which took place mainly on November 15 and 16, 1985, but continued until 1987 or 1988 on a smaller scale(Basiuk, p. 460.) – when men suspected of being homosexual were arrested and interrogated by the Citizen’s Militia,(The Citizens’ Militia (Milicja Obywatelska) was militarized police serving in Poland between 1944 and 1989, when it was ultimately transformed back into Policja (Police). The notion of “militia” has different connotations in the English language. However, throughout the text I refer to these Polish law enforcement services as Militia in compliance with the existing translation of the term in historical academic discourse (see A. Kemp-Welch, Poland Under Communism: A Cold War History, (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2008), and in order to retain its inherent character as the tool of political oppression of the citizens, differentiating the role of the Militia from that of the Police.) Kisiel felt liberated and believed that he did not need to hide his homosexual identity anymore, since, in his own words, “the Citizen’s Militia arranged a coming out for me. So…I decided to go all out.”(Kisiel, interview by Radziszewski, Kisieland.) However, Kisiel never decided to actively reveal his work in public, and so his collection of photographs and slides remained private. For a long time, the audience remained limited to original performers including Kisiel, his partner at the time and a close group of friends. In Radziszewski’s Kisieland, this private narrative is given the rare opportunity to present a counterstory to the one widely accepted as Poland’s official history. Kisiel’s archive is, in Judith Butler’s terms, performative, in that it is constituted through repetition, which effectively extends beyond the original 1980s’ material in Radziszewski’s work, adding new, ever-evolving contexts.(Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York: Routledge, 1990), p. xv.) Kisiel’s flat, seen as an archival project, restores the voice to the individual, but also emphasizes the fragility of the narrative as it enters the public discourse for the first time. It runs the risk of being obscured by the generally accepted dominant discourse, such as the religious influences and authoritarian politics of the Polish People’s Republic. It becomes clear from Radziszewski’s efforts to curate and document at least some part of Kisiel’s archive that unless such stories enter the public sphere, a rare and as of yet unaccounted for part of recent history may be lost irreversibly. However, since what we see in Kisieland is carefully selected material, directed and edited, it seems as though Radziszewski as much as Kisiel refrains from giving away the whole story to the public. The performativity of Kisiel’s archive remains to a large extent in the notorious closet, perhaps in order to evade its incorporation as part of the mainstream culture. The role of the informal queer narrative such as that of Kisiel’s archive is to infiltrate, disrupt, question, and ultimately provide an alternative to – rather than to reiterate – the dominant cultural discourse of the country.

“Operation Hyacinth” was a propaganda spectacle to create, within Polish society, the illusion that the government is fighting against allegedly socially harmful individuals, prostitution and the spreading AIDS epidemic.(S?awoj Kopka, “Hyacinth,” In Nation’s Service, no. 2, January 1986, p. 11.) The performative nature of the operation can be clearly seen in the almost theatrical raids of the Citizen’s Militia on not only private households, but also on schools, universities, and work places. The documentation of “Operation Hyacinth” remains inaccessible as its archive of over eleven thousand personal files is uncatalogued and scattered among various institutions, such as the Institute of National Remembrance, or the archive of the Polish National Police, none of which officially claim ownership of the documents. Therefore, it is currently impossible to trace the events of the raid in a definite manner. Any research can only be supported by personal accounts of the operation, which provide a fascinating insight. This approach, however, runs the risk of the information becoming convoluted or misrepresented by fading, incomplete or repressed memories. Many of the involuntary participants of “Operation Hyacinth,” including Kisiel, only agree to share some of their memories, but refuse to relive their clearly traumatic experience. Nevertheless, seeing “Operation Hyacinth” in the context of performance, I remember Amelia Jones’ remark, in her essay “’Presence’ in Absentia” (1997), that neither witnessing a performance live, nor afterwards in the form of a documentation, constitutes a privileged form of spectatorship. If this is so, we might then also consider the personal accounts of “Operation Hyacinth” as a legitimate source of information, especially since those (inaccessible) official files have almost certainly been tampered with and are therefore unreliable.(Amelia Jones, “’Presence’ in Absentia. Experiencing Performance as Documentation,” Art Journal. Art: (Some) Theory and (Selected) Practice at the End of This Century, vol. 56, no. 4, Winter 1997, pp. 11-18.) Therefore, as we analyze the stories found in the media, interviews, and other – often rudimentary – pieces of information, certain patterns emerge that emphasize the performative aspects of the raid. Many accounts by Kisiel; a gay activist Waldemar Zboralski; or the writer (and one of the initiators of Warsaw Gay Movement) Aleksander Selerowicz, emphasize the rigid structure of the operation. As they recall, “suspects” would be dragged out of their homes, workplaces, even cafés, given no time to fully comprehend the situation or protest:

“In the beginning I tried to protest but they intimidated me very quickly. I realized later, I mean after I regained consciousness and managed to calm myself down, that what they did was illegal… I could have refused. They threatened me, saying that my role could be changed and [from a witness] I could suddenly become a suspect… [Upon my release] I started going from flat to flat, visiting my … gay friends, to tell them about what was happening and inform them of their rights.”(Ryszard Kisiel, interview by Karol Radziszewski, DIK Fagazine. Before ‘89, no. 8, 2011, p. 30.)

Those who were brought in underwent a humiliating interrogation, and were forced to detail the nature of sexual acts they had performed with other men. Anonymity was promised only in return for undisputed cooperation and, in particular, for divulging the names of other homosexual men. By the end of the interrogation, which often lasted hours, every person was blackmailed into signing a statement confirming that they admitted their homosexuality, and had never had a homosexual relationship with a minor (as is often the case, any knowledge of such a statement only comes from oral accounts and popular media, whereas the official sources remain silent on the subject). The repetitive and almost choreographed actions, purposely directed to display power distribution and dehumanize the interrogated, bear all the marks of an intentional performative action. The theatricality of the officers’ behavior was designed to induce fear to which the interrogated were subjected as involuntary performers devoid of any initiative or possibility for directing the process. The use of the term “performer” here points to this performative character of the action, and the responses of the interrogated it had purposefully enforced. More importantly, however, it places the raid in a contemporary context. The voices of the interrogated emerge as they revisit their memories (apart from Kisiel, other activists, such as Waldemar Zboralski, have also spoken up about their experiences). In the absence of historical documentation, the oral histories provide a performative connection between the “there and then” and the “here and now” of “Operation Hyacinth.”

The performative nature of the raid requires consideration also in relation to communist ideology. Based on the ideas of a uniform community, it favored spectacular public acts of an inherently performative nature over singular voices, especially those of the non-conforming individuals. Under such conditions, Kisiel’s work, theretofore not presented to the public, acquired a necessarily political context. The inability to employWestern activist strategies that relied on high-profile public actions, such as the Stonewall riots or later ACT UP,(“AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) is an international direct action advocacy group working to impact the lives of people with AIDS (PWAs) and the AIDS pandemic to bring about legislation, medical research and treatment and policies to ultimately bring an end to the disease by mitigating loss of health and lives.” Source: http://www.actupny.org/ (Accessed August 14, 2017).) gradually developed strategies of activism performed in the private, which focused more on tightening the LGBTQ communities from the inside rather than on increasing its visibility to the outside. This reliance on private aspects of activism is particularly visible in Kisiel’s Filo, the first gay zine in Eastern Europe, founded in November 1986 in a direct, clearly political response to “Operation Hyacinth.” Working as a commercial printmaker, Kisiel knew it was legal to produce up to one hundred copies of any publication without seeking permission from the government’s censors; however the zine’s contents made its distribution a sensitive matter and ultimately the reason for Kisiel’s interrogation.(Kisiel, interview by Radziszewski, DIK, pp. 36-37.) While Filo supplied news on culture, politics, and lifestyle, it was its tongue-in-cheek manner, quirky word plays of a sexual nature, barely veiled critique of the government, and especially the explicitly homoerotic context of the publication that put Kisiel on the Militia’s radar. Significantly, it was also the only reliable advisor on safe sex practices and HIV prevention, at a time when the official sources had barely acknowledged the crisis spreading fast across Eastern Europe.

The private nature of Kisiel’s performative work was directly caused by the powerful political performance of communist ideology. As Basiuk writes, “Kisiel’s activism seems to mimic the state’s strategy while reversing its underlying assumptions.”(Basiuk, p.462.) The lack of possibility for free expression resulted in the birth of the performativity of the private, wherein the overwhelming metanarrative of the country’s totalitarian politics was confronted with the personal act of archiving potentially incriminating material. What facilitated the publication of Filo was the private aspect of its production and distribution. Kisiel posted Filo to his friends all over the country, who would then pass their copy on to someone else. Anticipating censorship of his correspondence, Kisiel aimed to use the postal service during the busiest periods, for instance just before Christmas. For the most part, Filo was accessible only to a relatively small circle, but it was this privacy that made it possible for the zine to spread to a wider readership than any official publication concerned with the same topics could. Not only was Filo an opportunity to share vital information on the AIDS epidemic and HIV prevention, it also provided gay people in Poland with an unprecedented sense of community.

Radziszewski’s Kisieland revisits Kisiel’s archive not only to restore the forgotten oral histories of communist Poland, but also to continue their community-forming potential. What strikes the viewer is that Radziszewski’s film, despite being meant for public viewings and despite the presence of a hired model and a cameraman, which necessarily disrupts the originally intimate character of the sessions, remains very much private. The interiors of Kisiel’s flat and Radziszewski’s studio used in the film are private spaces wherein the performance takes place. The scope of visibility is limited according to the authors’ intention and through the filmmaking techniques, using close up shots and the camera following the performers’ actions rather than capturing the whole scene including the interiors. The viewer is thus not allowed to wander through Kisiel’s archive, but only invited to have a glimpse in what Rebecca Schneider in her essay “Performance Remains” calls “a performance of access,” where the viewer’s access to performance is intentionally limited by the artist – such as edited film in the case of Kisieland.(Rebecca Schneider, “Performance Remains,” in Perform, Repeat, Record, Amelia Jones, Adrian Heathfield, eds. (Bristol, Chicago: intellect, 2012), p.145.) The question of performativity of Radziszewski’s work arises in relation to this staged transfer of knowledge described by Schneider. Eugenio Viola, the curator of Radziszewski’s solo exhibition The Prince and Queens. The Body as an Archive (held at The Centre of Contemporary Art in Toru? in 2014), writes: “…the work of Radziszewski brings into question the importance of selection … and the proper classification of data and documents; the difference between individual and collective memory.”(Viola, p. 27.) Radziszewski acknowledges limitations of one’s selective memory and his performative project is a reflection of this incompleteness, as Kisiel himself admits not recognizing certain materials in his own archive or not recollecting situations wherein some of the photos were taken.

Kisieland is an ongoing performative work that cannot be subject to reading detached from its original archive dating back to the 1980s. Kisiel as the author is an indispensable part of the work as an archivist of both documents and oral histories of the time, while Radziszewski takes up the role of medium for the distribution of the archival material as well as that of the interpreter. He continues Kisiel’s narrative, enabling it to develop through presenting and re-contextualizing Kisiel’s original slides in Kisieland. This continuity is also emphasized by the new photos taken of a professional model hired for the realization of the project. This was a significant element of Kisieland since, as Radziszewski said, his intention was not to repeat the original sessions, but:

“[T]o create a situation wherein not an artist, but … an amateur photographer … is placed in a context of an artist’s studio in Warsaw…It’s a test of sorts to see whether he thinks of himself as an artist, whether it [the 1980s’ sessions] was art, whether he is an artist now… Ryszard [Kisiel] proposed it was going to be a model…[I hired one] and Ryszard was confronted with…me as the artist with a diploma, documenting his actions. There’s a cameraman, a sound technician, the model, all of us following [Kisiel’s] ideas. At the same time,…there [was] also a documentary part where we registered the narrative deriving from the original slides…”(Personal interview with Karol Radziszewski, August 8, 2017, Warsaw.)

The model, therefore, entering the space of performance between document and art, became their meeting point in Kisieland, but also a negotiation of the ontology of Kisiel’s archive. Radziszewski chose photography not as a repetition, but rather a re-enactment and, consequently, an expansion of Kisiel’s archive. Entering the public sphere for the first time, this archive engages the audience in a performative play, simultaneously revealing some of its contents and pointing towards the elements that have been obscured. It thus enacts the refusal of the private archive of queer experience to subsume to the mainstream discourse of the nationalculture, which, in its inability toaccommodate an alternative (i.e. non-heteronormative) narrative in the public sphere, would reject and obliterate this archive. It also poses other limitations to the reader, as being retold from the point of view of Kisiel as its author this archive, embedded within the individual memory, lacks the deconstructive authority of a public deposition. Limitations preventing Kisieland from its inclusion into the public sphere do not, however, signify its failure as a narrative, but rather its performative and exploratory potential. As Basiuk writes:

“[T]he original slides’ performative engagement with the conditions determining the project’s legibility … needs to be repeated as another performative act by … Radziszewski, with the expectation that an aesthetic particular to … Kisieland will determine a new regime of visibility for the contents of the closet that are brought out into the open. This, however, does not mean that the closet disappears entirely, or that its content is fully determined by the particular access offered by its artistic presentation. The closet, like the archive, has more than one mode of access, and no particular enactment of access exhausts its content.”(Basiuk, p. 469.)

When researching documentation of reactions and media responses to Kisieland, which was a prominent part of The Prince and Queens exhibition (Toru?, 2014), it proves difficult to come across an in-depth analytical account of the work that does not come from Radziszewski himself. This raises a question of whether the theoretical framework exists in Poland that is able to tackle the discourse of queer art; it is what the exhibition appeared to ask, too. The display traced three different narratives: that of Kisiel; that of feminist art of Natalia LL and the reception of her feminist art in New York in the 1970s; and that of Ryszard Cieślak, the internationally celebrated actor of Jerzy Grotowski’s experimental theatre. The common point for these stories is their reliance on the oral histories existing outside the discourse of official culture. Their aim is to transform the well-known mainstream discourses, which is a central concern of Radziszewski’s practice. These unfolding narratives act as a bridge between the “then” of the communist country and the “now” of the arguably democratic one.

Working across time, Radziszewski positions Kisieland as a depository of the gay narrative, as a “testing the waters” of sorts, as it acts as one of the first attempts to initiate a dialogue between not only the past and the present, the public and private narratives of the same historical space, but also between the clashing national attitudes towards Polish LGBTQ communities today. Radziszewski reiterates the impossibility of detaching the archive from its “outside” as noted by Derrida, as well as of the separation of the “psychic apparatus” from archiving and reproduction that necessarily affect individual memory.(Derrida, p. 16.) Thus by returning to Kisiel’s archive, Radziszewski’s intervention is in the performativity of the private that, even though it does not enter the collective memory, still refers to it. This intervention poses a challenge, confronting the individual, thus far unknown narrative, with memories of the Polish People’s Republic established within the collective national consciousness. Significantly, as archival traces of “Operation Hyacinth” are being kept inaccessible, the once dominating political metanarrative is now being replaced with the emerging personal account of history.

One of Radziszewski’s newest works, Ceremony (2016) is a twenty-minute long, static video piece exhibited at Late Polishness exhibition (2017) at the Centre for Contemporary Art in Warsaw. The work is a performative ritual, featuring Radziszewski in a costume inspired by Kisiel’s “Indian Shamaness” character, which the latter employed in a series of photographs relating to the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s. Also present is a naked male model with a phallus painted on his chest and stomach, and a red heart marking his penis. The slow camera movement follows Radziszewski opening a bottle of champagne and lighting candles, and then sitting down on the grass, as if to meditate. The model, standing up, lights one cigarette after another, and only inhaling once or twice, puts them down – still lit – in a clay pot between the two men. Behind, there is a stone mosaic forming an apse, which frames the set of the performance in an altar-like composition. The ritual evokes the spirit of Maria Padilha, an Afro-Brazilian enchantress, belonging to the class of female spirits Pomba Gira. Kelly Hayes writes that:

“[Pomba Gira] is said to specialize in love magic: attracting and keeping a lover, orchestrating betrayals, arranging illicit paramours, provoking intrigues – the complex affairs of the heart represent her characteristic field of action. … [S]he must be persuaded to aid her human followers with flattery and gifts, most especially items that gratify her vanity or satisfy her vices: sweet wine, cigarettes, perfume, jewelry.”(Kelly Hayes, “Wicked Women and Femmes Fatales: Gender, Power, and Pomba Gira in Brazil,” History of Religions, vol. 48, no. 1, August 2008, p. 2.)

Radziszewski’s choice to relate it to the “Indian Shamaness” employed in Kisiel’s works on AIDS, is a further opening of the activist’s archive. Here, it functions as a utopian turn toward the future. Radziszewski claimed on different occasions that Polish culture is problematically desexualized: “When it comes to the Polish context and body … the main problem is that we didn’t have a real sexual revolution, which would … neutralize certain themes,” such as homosexuality or sexual pleasure.(Radziszewski, interview by Daria Szczeci?ska, Dorota Ruczy?ska, Wojciech Krzywdzi?ski, “I Filter Archives Through Myself,” http://www.e-teatr.pl/pl/artykuly/194017,druk.html (Accessed April 4, 2017).) In Ceremony, he examines whether and how the discourse of sexual jouissance could be restored into the Polish public sphere. He ponders on whether the unearthing of Kisiel’s archive that documents now-lost pre-AIDS sexual cultures could have a healing effect on Polish society and its public sphere’s lack of representations of erotic pleasure. Through ritual evocations of desire, love, eroticism, and affection, Ceremony strives to dismantle the trauma of the AIDS epidemic and its aftermath. The work is important in the context of the Late Polishness exhibition. Despite the promise of its title, which suggests a rethinking of what “Polishness” means today, the display reiterates the nationalistic themes of conservatively traditional, Catholic traits of Polish identity. It employs, as Karol Sienkiewicz writes, “an avalanche of white and red works, crucifixes, Virgin Mary, the Polish … pope, [and] Lech Wa??sa …”(Karol Sienkiewicz, “White-and-Red Corner,” dwutygodnik.com, April 2017, http://www.dwutygodnik.com/artykul/7154-kacik-bialo-czerwony.html (Accessed May 1, 2017).) This suggests that the narrative of difference is still marginalized as part of Polish identity. The inclusion of Radziszewski’s work into the exhibition, and the artist’s attempt to introduce sexuality into the public sphere, are a significant transgression of the solemn seriousness of the Polish national identity. The performative context of Ceremony as a rite of passage, the time-binding performative gesture, signals the arrival of the new. “Queerness,” José Muñoz writes in Cruising Utopia, “is not yet here.”(José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia (New York: NYU Press, 2009), p. 1.) We may, he claims, never get there, but it is my contention that Radziszewski in his work imagines Muñoz’s “new and better pleasures, other ways of being in the world, and ultimately new worlds.”(Muñoz, p. 1.) Unearthing Kisiel’s archive and its performative reinvention allowing its expansion into a continuing narrative, Radziszewski’s utopian striving invades the public sphere with the statements of sexual jouissance, just as the viral nature of Kisiel’s activism infiltrated the stale public sphere of the totalitarian regime.

This work was supported by Northern Bridge Doctoral Training Partnership and the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

This article is part of the Special Issue on Reenactment in Eastern Europe. Articles in the issue include:

[su_menu name=”Reenactment”]

Aleksandra Gajowy is a PhD candidate at Newcastle University, UK. Her doctoral project focuses on the representations and ontology of the queer body in performance and body art in Poland from the 1970s to the present, with particular focus on censorship, the Catholic Church, and HIV/AIDS narratives. Gajowy research has been funded by Northern Bridge Doctoral Training Partnership, the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

Aleksandra Gajowy is a PhD candidate at Newcastle University, UK. Her doctoral project focuses on the representations and ontology of the queer body in performance and body art in Poland from the 1970s to the present, with particular focus on censorship, the Catholic Church, and HIV/AIDS narratives. Gajowy research has been funded by Northern Bridge Doctoral Training Partnership, the Arts and Humanities Research Council.