Participatory Practices in Hungarian Contemporary Art (Article)

Participatory art projects are not common in the Hungarian visual art scene. If we see this kind of artistic activity as having something to do with social engagement, it might be easier to understand its rarity. After a rising interest at the turn of the century, only a few artists have continued to develop socially engaged projects in the past few years. The art scene is not receptive to self-restricting artistic activity and autonomy.(See texts on some art collectives of the 1980s and 1990s (the Újlak Group, Szürenon, INDIGO etc. in IMPEX: We Are Not Ducks on The Pond But Ships at Sea, Budapest, 2010.) Still, there are a few artists who deal with the social fabric and engage in political or social activities, even activism. I would like to introduce some projects that deal with communities and can therefore be identified as community or participatory art projects. These projects were created for various contests: the first was put on by the Ludwig Museum in Budapest, the second by the Ministry of Economy and Transport in 2003, and the last projects for the Hungarian Art Council’s public art contests in 2008 and 2009.

Debates about social engagement and participatory artistic practices strongly relate to the development of a new public art and the public discourse on traditional and New Genre Public Art.(Suzanne Lacy, ed. Mapping the Terrain. New Genre Public Art (Seattle: Bay Press, 1995).) As Dóra Hegyi, the curator of the Moszkva tér – Gravitation public art exhibition writes in the project’s catalog, the term “Public Art” signifies a new, progressive art form on the Hungarian art scene. She describes various public activities that remain distinct from the more common forms of art in the public space, such as monuments and traditional public sculptures. Public Art helped create a new discourse concerning not only public and private space and the position of the audience and the artist, but also the social role of the artist and the possibilities of his/her social engagement. The first big public art event, Polyphony 1993, presented mainly site-specific artworks for projects outside of galleries and museums. Ten years later, most of the projects produced for the Moszkva Tér-Gravitation show dealt not only with the physical, but also with the social characteristics of the space.

Moszkva tér (Moscow Square in English) plays a tenuous role in Budapest’s daily life, with its central location offering a painful reminder of the past. The square is a point of convergence for many different social groups: the affluent classes from the Buda part of the city, the homeless who sleep next to the metro station, and teenagers who gather there on Friday nights. One part of the square has even become a black market for human “resources.” Real estate prices have soared in this part of the city, though the square itself has not been reconstructed since the 1970s. Not only does its name remind us of the time when Hungary had close political relations with the Soviet Union, but its very architecture carries many memories. The revitalization of the square is an issue that has been raised by many politicians and civil groups. Many different architectural plans have been proposed, but any final decision concerning the future of the square has been postponed.

With his project Balázs Beöthy sought the participation of panhandlers by asking them to hand out money to passers-by in the square, thus reversing the familiar and common social action of begging. In a similar vein, János Sugár collected the life stories of anyone willing to talk to him for 10-15 minutes in return for 4000 forints. The interviews were conducted in a van standing in the middle of the square, usually the gathering place for the black-market workforce. These stories were later published anonymously in the project’s temporary periodical, Time Patrol. In the opening ceremony, the group Hints (of which I was a member at that time) organized a free meal open to everyone in the square: from the homeless to journalists and members of the artistic community. Ideally everyone would have been invited to an opening event but unfortunately the parallel VIP buffet at the Gomba café divided the people in the square and offered an escape route for those who were not interested in becoming part of the crowd. As a result, those people who had been asked to participate instead became passive observers.

Another open commission that contributed to the discourse on public art was organized by the Ministry of Economy and Transport in 2003. The ministry, getting ready for Hungary’s joining of the European Union in 2004, announced a call for Public Art projects in rural areas and small towns that would reflect the changes faced by the small regions of Szob and Nagykáta. The aim of the program—Spaces of Constructive Discourse („Konstruktív Párbeszéd Terei”)(Spaces of Constructive Discourse, texts available on January 2009: http://www.nfgm.gov.hu/data/cms12764/sajt_anyag.doc.) —was to generate active dialogue on the issue of Hungary’s joining of the European Union through art. Before the commission, preliminary discussions were organized by the Ministry and a British curator, Sophie Hope, so that art historians, artists, curators, sociologists, communication professionals and public administrators could engage in an open dialogue. Two projects were commissioned: one for the Szob region, and the other for Nagykáta.

Endre Koronczi’s Csetteg? Project was a beauty contest for what in Hungarian is called csetteg?, homemade motorized devices used for agricultural work around the house and in the fields. These gadgets are remnants of the socialist past, when modern technology and machines were unattainable for ordinary people in the countryside. Csetteg? are a mixture of socialist-era cars, agricultural engines, and any practical tools that once lay around state-owned collective farms. After the changes in the political and economic system, these machines could not be replaced because the country remained poor.

Endre Koronczi’s Csetteg? Project was a beauty contest for what in Hungarian is called csetteg?, homemade motorized devices used for agricultural work around the house and in the fields. These gadgets are remnants of the socialist past, when modern technology and machines were unattainable for ordinary people in the countryside. Csetteg? are a mixture of socialist-era cars, agricultural engines, and any practical tools that once lay around state-owned collective farms. After the changes in the political and economic system, these machines could not be replaced because the country remained poor.

Csetteg? Project demonstrates the power of human creativity under any conditions. By highlighting the uniqueness of this tradition of bricolage, Koronczi defines and reinforces the identity of the local community. The forms his project took were the beauty contest itself, a media campaign designed to promote the contest (with a web page), and finally a film made by the ethnographer Péter Lágler that documented the project and created portraits of the competing inventors.

The second winner of the Ministry’s contest was a project by László Gergely (Nagykáta region) entitled Commuting Artillery (Ingázó tüzérek). The project connected two regional specificities. The first is commuting, since many people from the Nagykáta region have to travel to Budapest on a daily basis, using the few private bus companies that can provide transportation for them. The second local tradition addressed by the project is the regular re-enactment of the 1848 bourgeois revolution and the 1849 war of independence (from the Habsburg Empire) by local groups who groups who want to keep the memory of these events alive. Every year on April 4th, these groups reenact the battle of Tápióbicske where the Hungarian troops defeated the troops of the Austrian empire. Gergely made a series of portraits of the three re-enactment groups while they were preparing for the event; on the day of the battle he placed forty-four of these portraits on five buses that regularly commute in the region. The portraits stayed on the buses for three months. Gergely wanted to highlight the problem of unemployment that forces many of the local residents to commute day by day to distant factories. Apart from that he wanted to highlight the power of historic memory in keeping disintegrating communities together.

I decided to introduce these projects from the first half of the decade to demonstrate how these themes have continued in some projects developed in the past few years. In the period from 2003 to 2004 one of the crucial elements of Hungarian art discourse, at least on an institutional level, was the position of such organizations as museums, ministries, and councils in regulating public space and the art that can be found in them. The activity of the Hungarian Arts Council (Képz?- és Iparm?vészeti Lektorátus) was often a target of criticism. The council was established in order to regulate artwork in the public space and it tended to dominate the official discourse regarding the value of such works, mostly traditional sculptures and monuments.

Claire Bishop finds three characteristic agendas with which participatory artworks are allied: activation (of the subject), authorship and community.(Claire Bishop, ed. Participation: Documents of Contemporary Art (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2006).) In the early 2000s, activation and authorship dominated in Hungarian art practice, a fact that is indicative of a wish to redefine the positions of the artist and the spectator, as well as experience of art. The above-mentioned two projects were commissioned by the Ministry of Economy and Transport and responded to the utilitarian aim of activating and empowering citizens, in the hope that “newly-emancipated subjects of participation would find themselves able to determine their own social and political reality.”(Ibid., 12.)

At the same time both Csetteg? and the Commuting Artillery relate to the representation of the community and a wish to strengthen it through participation. As Bishop explains, the agenda of the communities in participatory projects “involvesa perceived crisis in community and collective responsibility. This concern has become more acute since the fall of Communism, although it takes its lead from Marxist thought that indicts the alienating and isolating effects of capitalism. One of the main impetuses behind participatory art has therefore been a restoration of the social bond through a collective elaboration of meaning.”(Ibid.) The changing social conditions of post-socialist Hungary and the effects that socialist times and later transitions had on the community are cardinal issues in Koronczi and László’s projects.

The ongoing professional discourse on public art changed by the end of the decade. In 2008, in cooperation with the Ministry of Culture, the Art Council organized a huge public art contest in eight cities; five more were organized in 2009 (in that year, a call for public projects in small towns went out). Gergely László and Péter Rákossy (calling themselves Tehnica Schweiz) made a long-term project in some private garages in Dunaújváros. In this socialist city, there are several parking areas with closed garages that were built in the 1970s. For example the bus company Volán has 1200 unique concrete garages, most of them still in use, while others are empty or used as workshops.

In the first phase of the project László and Rákossy visited many of these garages, talked to the owners and documented the interiors. Behind every identical garage door there are different wonderlands created by the owners during their escape from their daily routines.

In the second phase of the project, Technica Schweiz rented an empty garage and started to think about the different worlds that could be imagined inside. They invited other artists and friends to design their own spaces. These interiors were then photographed.

Then at the end there was the “garage festival” during which all the owners, their families and their friends were invited to celebrate and to show their own garages. In addition there were performances, music, and sometimes even a cooked communal meal. The festival also involved an exhibition, the Garage Museum, where different objects were collected from the garages to recall their past. This community event was organized with the help of young locals who have since arranged a second festival and who see the project as a new tradition, a community event they want to recreate every year.

Probably the most interesting project of the 2009 commissions for small town projects wasRe-habilitation by Katalin Tesch and Ildikó Szabó. In the border region of ?rség, as in many other regions of Hungary, ageing is a major problem. Young people and their families move to bigger towns for education or work, leaving their old relatives behind. Empty houses, school buildings and decaying infrastructures show the decline of these old settlements.

Ildikó Szabó spent part of her childhood in the village of Hegyhátszentmárton, which today is also becoming an abandoned site. The two artists decided to create a project that would help local inhabitants discuss the problems caused by the migration of their families and friends, and their feelings of the emptiness left behind. During her stay in the village, Ildikó collected stories and memories of the inhabitants, trying to understand what happened in the past fifteen to twenty or even fifty years. Why did people leave and what did they leave behind?

The main element of the project was a public installation. The artists collected photographs and portraits of those who either died or left. These pictures were printed on black balloons and for ten days in October of 2009 they were placed in the streets of the village; each balloon was set in front of the house where the person depicted on it once lived. This gloomy and sentimental picture of streets filled with black and white portraits printed on black balloons provided an opportunity for the neighbors to discuss their feelings and to re-create a public debate about the past and the future of the village. Additionally, the artists made a short video not only documenting the project, but also interviewing the people about their views on this social issue. This video was yet another element that helped individuals remember their community. The video also refers to a television documentary made in the 1980s by Hungarian national television which presented the village at that time and which is still often recalled by the people of the village who were proud of this exposure. The artists hope this project and its documentation will become a similar reference point in a few years.

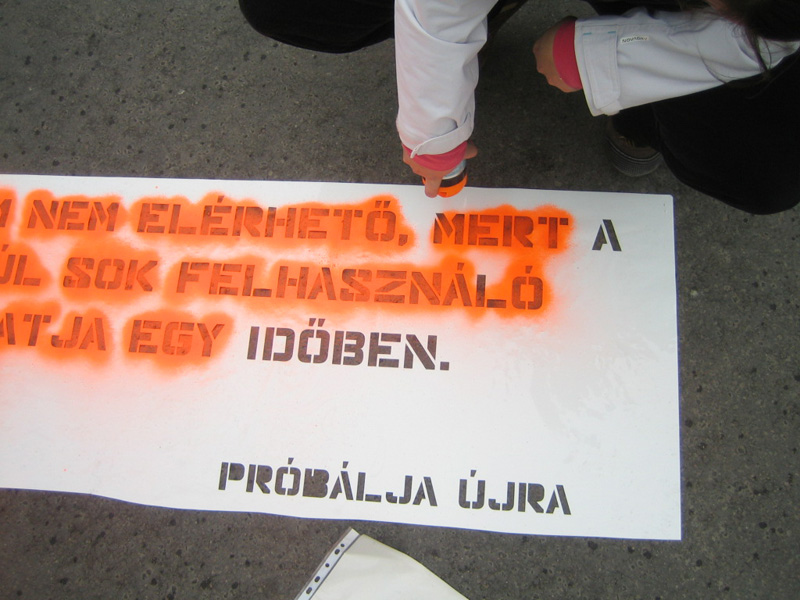

Re-habilitation was not the first community project that Tesch and Szabó created together. Their first project, Street Pop Ups, was designed in response to a call by three NGO’s (Hungarian Young Greens, IMPEX – Contemporary Art Provider, and the Sun Club Foundation) whose work is connected to District VIII in Budapest. The center of this district is run down and inhabited by poor families, mostly Romany, and has developed a reputation as the city’s ghetto. The three organizations made an open call in April 2008 for a participatory/community art project that was to be made in the Magdolna Quarter of the district, with the participation of the local inhabitants. The jury selected the proposal by Katalin Tesch and Ildikó Szabó. Originally titled Magdolna Computer, the project was inspired by Windows error messages. The two artists interviewed people on the street about their opinion of the quarter, collecting messages that people would send to their neighbors concerning the state of the area and what could be changed in it. The artists transcribed these messages into the format of a computer error message. Some of these messages were positive and constructive, but there were also many harsh and critical ones that reflected the negative feelings people have concerning the state of their streets. These error messages were then sprayed on the streets of Magdolna Quarter and the artists documented the reaction of passersby in photographs.

Re-habilitation was not the first community project that Tesch and Szabó created together. Their first project, Street Pop Ups, was designed in response to a call by three NGO’s (Hungarian Young Greens, IMPEX – Contemporary Art Provider, and the Sun Club Foundation) whose work is connected to District VIII in Budapest. The center of this district is run down and inhabited by poor families, mostly Romany, and has developed a reputation as the city’s ghetto. The three organizations made an open call in April 2008 for a participatory/community art project that was to be made in the Magdolna Quarter of the district, with the participation of the local inhabitants. The jury selected the proposal by Katalin Tesch and Ildikó Szabó. Originally titled Magdolna Computer, the project was inspired by Windows error messages. The two artists interviewed people on the street about their opinion of the quarter, collecting messages that people would send to their neighbors concerning the state of the area and what could be changed in it. The artists transcribed these messages into the format of a computer error message. Some of these messages were positive and constructive, but there were also many harsh and critical ones that reflected the negative feelings people have concerning the state of their streets. These error messages were then sprayed on the streets of Magdolna Quarter and the artists documented the reaction of passersby in photographs.

The two projects are based on the idea that the artist’s interaction and activity within a community can raise public awareness and perhaps help redefine social issues. They can be identified as discursive and dialogical artworks.(Grant H. Kester. “Community and Communication in Modern Art” in Conversation Pieces, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004).) Although they are based on an active research period, involving methods similar to social research, it is never the goal to reach total consensus. Instead the goal is to intensify the focus on certain topics that reappear in everyday public discussions.

The two projects are based on the idea that the artist’s interaction and activity within a community can raise public awareness and perhaps help redefine social issues. They can be identified as discursive and dialogical artworks.(Grant H. Kester. “Community and Communication in Modern Art” in Conversation Pieces, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004).) Although they are based on an active research period, involving methods similar to social research, it is never the goal to reach total consensus. Instead the goal is to intensify the focus on certain topics that reappear in everyday public discussions.

In his concept of the Four Stages of Public Art, following the argument of Hal Foster,(Foster, Hal. “The Artist as Ethnographer” in The Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1996).) Mark Hutchinson has described the activity of the artist as the work of an anthropologist: first being an “objective” observer, then developing self reflection and the feeling of agency, and finally actively getting involved and creating a reciprocal connection with the people observed.(Although there are a few projects in visual arts that respond to this interest, a more vibrant discourse seems to be developing in the theater. See Mark Hutchinson. “Four Stages of Public Art”, Third Text, Vol. 16, Issue 4 (December 2002), 429 – 438.) But what can ethnographers and anthropologists be to artist-initiated projects? The community projects I described above not only involved strategies similar to those used by anthropologists, they also piqued the interest of social scientists and were sometimes created with the collaboration of researchers. Péter Lágler, an ethnographer and filmmaker, was actively involved in developing, documenting and analyzing many of these projects. He was strongly involved in Endre Koronczi’s Csetteg? Project and documented it in his film Mechanical Folk Art (Gépm?vészet, 2004). His film is a separate interpretation of the project and the social activity it represents and is thus both a parallel work of art and an ethnographic film.

As part of the Art Council’s commission for community art projects in small towns, Lágler and a team of researchers documented the projects and created a method to analyze their effect on the inhabitants. They interviewed the mayors of the towns, artists, and locals a week after the public opinion surveys were distributed. This helped them analyze the level of the inhabitants’ involvement in the projects. Many of the questions were connected not to the artwork, but to its subject matter – the relation of the people to their hometown. Thanks to these additional activities, these art projects became tools for accumulating knowledge both on social issues and art. From the perspective of the humanities and the social sciences, interest in socially engaged art and participation still seems to be growing, as participation is currently a popular issue in these fields.(Krétakör Majális, Pécs 2010 – www.kretakor.blog.hu – or the programs of the Káva Theatre (www.kava.hu).)