Otranto – A Time-Based Monument to Albania’s 1997 Migration: A Conversation with Latent Community

This interview focuses on the film Otranto (2019–2020), created by the artist collective Latent Community (Ionian Bisai and Sotiris Tsiganos). Otranto explores a relatively unknown tragedy: the story of the refugee ship Katër i Radës. The ship departed from the Albanian port city of Vlora, carrying 120 people fleeing the violence that had engulfed the country following the massive collapse of pyramid schemes in 1997. On March 28, 1997, the Italian navy warship Sibilla—acting in accordance with an Italian blockade of Albania to prevent refugees from entering the country—intercepted, rammed, and sunk the Katër i Radës in the strait of Otranto, killing 81 of the refugees aboard. Among the victims were many women and children, some not even a year old. Otranto follows a group of Albanians who lost family members in the tragic event, as they journey to Italy to take part in court proceedings (which have dragged on through various trials over the interim decades, without resulting in justice that the families can accept). The film itself serves as one kind of monument to this loss of life, and its narrative revolves around another monument: the wreck of the Katër i Radës, which the Italian government had transformed into a monument in 2012, and which now stands in the town of Otranto, despite the demands of the families that it be returned to Vlora.

Latent Community (Ionian Bisai and Sotiris Tsiganos), still from Otranto, 2019-2020. Video, Full HD, Color, Sound (DCP), 24:41.

Raino Isto: The story of the Katër i Radës is relatively unknown outside of Albania, but within Albanian discourse it is an indelible part of the tragic memory of the upheavals of 1997. The event entered the repertoire of kurbet songs, Albanian songs that reckon with the sadness and loss of emigration. How did you decide to make a film about this event?

Ionian Bisai: This project has to do with my Albanian background. When the events that are discussed in the film took place, I was 5 years old, living in Greece. It was a time when migration was the dominant reality in Albanian life, due to the collapse of the pyramid schemes and the ensuing kind of civil war that took place in the country. The period of 1997 was a time of conflict that, I think, creates the whole contemporary identity of Albania. I think it’s very important to deal with the issues raised by the memory of that time, because it was at the same time the period when an Albanian national identity was constructed based on mourning—mourning was being used to bring together and construct a nationalistic sense of identity. So there are also problematic elements to this memory of 1997, and that is also a part of the film Otranto, providing a counter-narrative to the superficial narrative the national government and the press created at the time.

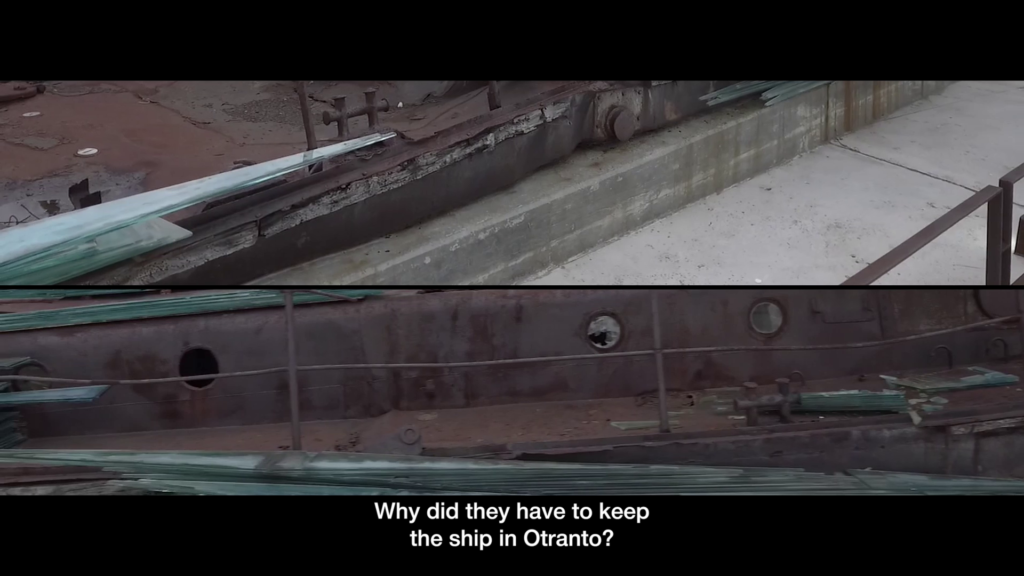

Latent Community (Ionian Bisai and Sotiris Tsiganos), still from Otranto, 2019-2020. Video, Full HD, Color, Sound (DCP), 24:41.

Another inspiration was all of these polyphonic songs I remember hearing when I was growing up, in Albanian culture, songs that have to do with remembrance, with preserving the memory of events like this one. I decided, with Sotiris, to find a way to use art to bring back the missing memory of this story, which is almost forgotten outside these specific communities. Finally, we were interested in the way the Katër i Radës itself, as a work of art, played a role: turned into a monument, it also became a way of hiding the evidence of a crime in plain sight.

RI: Otranto follows a group of family members of those who were killed in the tragedy, as they make a voyage to the city of Otranto. Through the first half of the film, we hear some of their stories about the family members they lost, and we see their grief. How did you first get in touch with the families, and how did they react to your making the film?

IB: My father comes from a place near Vlora, so he has some relatives there, and they helped us approach the families. In the beginning, they were afraid of working with us on the project, because they have had such bad experiences with the press, and with politicians. But then we started to discuss with them the idea of making this film, and when we explained to them that we wanted to give them space to show their own rituals, their own ways of mourning. We didn’t just want to extract from that them, from that community—we also wanted to give something back. At the time we were working on this, the group of relatives needed to travel to Italy to attend a very important trial, part of the case that is still ongoing, and so we combined that journey with the making of our film. The trip they take is not something they do every year. Yearly, they have their own ritual, which they do in the port of Vlora, where they throw flowers into the sea. But this trip to Italy was specifically for them to participate at the trial. We found a common point in order to collaborate, a space to be able to include their demands.

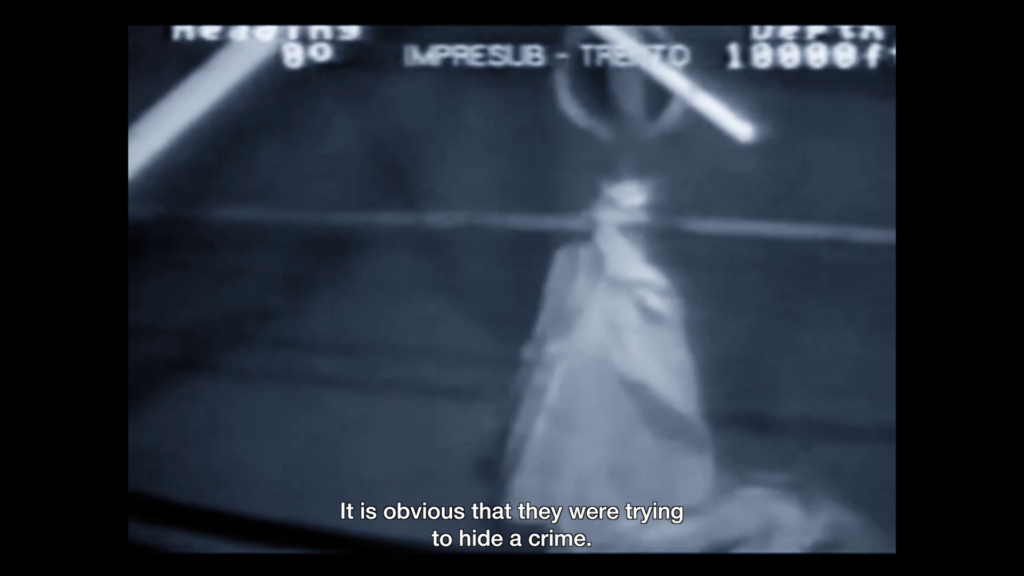

Latent Community (Ionian Bisai and Sotiris Tsiganos), still from Otranto, 2019-2020. Video, Full HD, Color, Sound (DCP), 24:41.

Sotiris Tsiganos: I would say that a turning point in the process was when they understood that we didn’t want to make a project about them, but with them. And from that point, slowly but steadily, we started building a relationship with this community. When they were able to see beyond the words and see what our real intentions were, things started to work.

RI: One of the conflicts that Otranto identifies concerns the Katër i Radës itself, as you mentioned. The Italian government kept the ship in Italy, and in January of 2012 commissioned the Greek sculptor Costas Varotsos to transform it into a monument, ironically titled The Landing (despite the Katër i Radës having been precisely prevented from landing). The ship is now located in the city of Otranto, and in the film, the family members express their anger that the ship not being returned to Albania. The transformation of the ship into a monument removed the possibility of it being used as evidence of a crime (since the trial was still ongoing), and in a way ensured that justice could not be done.

IB: This was something with which we found common ground with the community of the families: we were united with them against that, and we looked for ways to criticize this aesthetic co-opting of evidence. We wanted to reflect on this idea of monumentality, and on the community counter-narration: the family members were demanding that the ship should be taken back, to Vlora. Because in many cases, since they did not find the bodies of those who were on board, the ship was to them a kind of memorial object that they wanted returned to them, as a way to remember. These kinds of debates, about authoritarian monumental practices, and the community’s own contesting narration, helped us build the idea of the project.

Latent Community (Ionian Bisai and Sotiris Tsiganos), still from Otranto, 2019-2020. Video, Full HD, Color, Sound (DCP), 24:41.

RI: Otranto has a curious structure: it begins with a circle of people at prayer in front of the Katër i Radës monument in Otranto, and after they conclude their prayer, we see them speaking—in Italian—to the woman who later emerges as the protagonist of the film. Otranto concludes in the same spot, as the woman stands and reads aloud the names and ages of the 81 refugees who died in 1997. Between these two parts, the film takes place on the water: we see the ship slowly unmooring and setting out to sea, and we travel with the family members to Italy, hearing their memories of the event as voiceovers. Later, as we see archival footage related to the event, before finally returning to the monument of the Katër i Radës and the reading of names. How did you decide on this structure?

IB: Our decision on how to open and conclude the film came about because of some strange, unexpected events. The opening scene of the film actually came at the end of shooting, after we shot the reading of the names: a group of Catholic Christians happened had come to the site to read aloud a prayer for migrants. This was a prayer that had been written by the Pope regarding the crisis in Lesbos. So the opening scene in fact has to do with another situation, seen through the lens of a religious ritual, but we decided to keep that as a strange opening to the film. It’s an opening that links different parts of the Mediterranean in a symbolic way, showing how this issue of immigration and refugee movements ties the region to the whole world. Placing this part at the beginning let us establish the list of names at the beginning, because the woman explains it to these people who have come to pray. We found it poetic.

ST: It was also our intention, through the pace and the editing of the film, to have the same starting and ending point, to make a circle. This emphasizes the open-ended character of this ongoing quest for justice.

IB: We also wanted it to be an open-ended film, because we aren’t the people to say that the situation is closed, that it is resolved. We don’t have that right. The only thing that is stable is the journey the family members take, their struggle for years to achieve justice.

Latent Community (Ionian Bisai and Sotiris Tsiganos), still from Otranto, 2019-2020. Video, Full HD, Color, Sound (DCP), 24:41.

RI: You describe the film Otranto as a “time-based monument,” and you use it to raise questions about monuments our present moment: do we need monuments that endure, or (counter-) monuments that are even more flexible, inclusive, and fluid in their relationship to particular spaces and times?

ST: As you know, the whole region of the Balkans is very conflicted, especially when it comes to the issue of monuments—how they are used and how they are interpreted. But I would say that in Otranto there are two issues. One is our more critical approach to the way that Katër i Radës itself was turned into a monument, how that abuse of the ship turned it into a whitewashing tool used to hide the evidence of a crime in plain sight, to place it outside the context of the case. On the other hand, we see our whole film Otranto as a monument, as an apparatus to both preserve memory and spread awareness about the events that took place. We differentiate between a spatial monument, and a time-based monument, which is what we call the film.

IB: We have seen many cases where objects have been transformed into art objects, extracted from their contexts as the artist gives them a new identity and tries to capitalize on them in the context of the ‘attention economy.’ In these cases, the artist misrepresents the meaning of the original context, of the events, like the case of Christoph Büchel at the 2019 Venice Biennial, where he took a refugee ship and exhibited it at this big biennial. We didn’t want to make something like that; instead, we wanted to push the limits of what it means to create a counter-monument, a more inclusive monument, one that focuses on the people that are linked to this history. We didn’t want to exclude them, or to just use them to create the piece.

RI: Otranto is about documenting and preserving community practices of memory, and also about keeping alive demands for justice where no justice has been served. What role can contemporary art play in the quest for justice?

ST: Our approach and our perspective mostly focused on the more personal, more emotional aspects of justice. We wanted to show the empowerment of the community in their quest for justice. Obviously, there are more explicitly forensic approaches to justice in legal cases, but our approach is more of a social approach to justice. As artists, we also wanted to serve as a sort of bridge between this missing story, which is not widely known, and society.

Latent Community (Ionian Bisai and Sotiris Tsiganos), still from Otranto, 2019-2020. Video, Full HD, Color, Sound (DCP), 24:41.

IB: For us, the quest for justice has to do with creating a place where we can create empathy between a particular community and society. We want to create a space where these stories can circulate, and also where we can raise awareness, especially about the issue of migration in general, which is so prevalent in the Mediterranean region.

RI: Recently Southern and Southeastern Europe has been a key territory in the movement of refugees, from countries like Libya, Syria, or Afghanistan. The movement of refugees always raises questions about borders, about who comes from “outside” and who has the right to live “within.” Otranto draws our attention to the violence that is done to preserve borders and divisions.

IB: For us, it’s really important to give personal space to all these victims of refugee tragedies like this one. Because in many cases, we don’t know anything about them as people, we don’t know the human side, and then as a society just approach them as statistics or numbers. With Otranto, we wanted to show how the personal becomes political. We wanted to start to give the appropriate space to all these victims, to create a context for understanding other cases, where all we have are numbers. We wanted to make a space where this individual story could become something more universal, by giving appropriate space to the trauma and acknowledging how the family members have been affected by it.

We worked with a local issue, with the aim of making it more global. Our film links it emotionally to other cases, through empathy, also in order to destabilize the kind of nationalistic narrative of mourning that I mentioned earlier. We wanted to give the mourning a global dimension.

ST: While we were making the film—of course it’s still going on—we were fed up with the way the media covered the refugee crisis, and also the way that a lot of artists participated in sensationalizing it and treating it as something new. With Otranto, we tried to take a step back, avoid the narrative of the media, and look at a story that seems like maybe it is old, or forgotten. This gives us the space to explore the topic, but also its aftereffects. It was really important for us to go beyond the immediacy of the media, to go beyond shocking images, to see how people’s lives are changed by this two decades after. Because in the news, these stories just end—it cuts to a commercial. But these tragedies, these stories, and these memories are alive; that is what we show in the film.

IB: We also looked at this issue through the lens of necropolitics. Because the Italian (and in fact the European) immigration policy is becoming even more strict, like in America as well, where we saw with all the efforts to blockade the border and stop these caravans of immigrants. These strict immigration policies have a necropolitical aspect, of who is allowed to live and who can die, whose death counts as something that can be remembered. In the case of the Katër i Radës, this was really important: it was the first time that a navy ship used military maneuvers to strike a migration ship, a ship carrying refugees. And in the context of the Mediterranean, this was one of the most terrible blockades of migration.

Latent Community (Ionian Bisai and Sotiris Tsiganos), still from Otranto, 2019-2020. Video, Full HD, Color, Sound (DCP), 24:41.

RI: Otranto is not your first film to address the element of water. In Neromanna (2017), you tell the story of the village of Kallio in Greece, a village submerged in 1981 beneath the surface of Mornos Lake, an artificial lake created to supply water to Athens. In that film, you explore the memory that the residents of this village have of their town, now consigned to oblivion beneath the water. Bodies of water are so often part of stories of loss, and the fluidity of water can serve as a metaphor for perpetual transformation. Could talk about your relationship to water?

IB: We started with Neromanna as a case study into water. We understand water as a kind of liquid database: we can learn a lot of things about human and nonhuman ecosystems from water, and find many ways to link ecological and social topics together through water. In water’s fluidity, we found new ways of approaching our existence as humans, and our relationships to other humans as well. This notion of fluidity helps us understand that in the contemporary moment, we don’t necessarily need permanent things anymore: we need to be able to “go with the flow,” so to speak, to understand the constant change that is at the root of issues of ecology, of migration.

ST: I would add that because we are both born and raised by the sea, we have this very intimate relationship with the element of water. It has a certain effect in our vision, and our way of thinking. Even though there maybe wasn’t a strategical intention to work on subjects related to water, it seems like it was something there underneath, pushing us to work around this element.

IB: We found that the liquid state of water become an apparatus for examining these topics, a conceptual approach that allows us to be critical of things that look stable and solid. The fluidity of water as a metaphor also creates a certain sensitivity for us in the approach to our topics, to adapt to the flow of situations—and the emotions or the relationships that develop in making a project—to be sensitive about the topics we work on. It wasn’t there at the beginning explicitly, but when we discovered that sensitivity, we started to use it as a tool.

This interview was conducted via Zoom in October 2021. It has been edited for length and clarity.

This article is part of the Special Issue Contemporary Approaches to Monuments in Central and Eastern Europe. You can find links to the other articles in the special issue below: