On the Void: Elżbieta Tejchman and The First Biennale of Spatial Forms in Elbląg, Poland (1965)

Landscape photography plays a crucial role in portraying the social and political order. As early as 1936, Walter Benjamin saw a critical potential of this genre. He compares photographs by Eugene Atget to pictures taken at crimes scenes: “A crime scene, too, is deserted; it is photographed for the purpose of establishing evidence. With Atget, photographic records begin to be evidence in the historical trial [Prozess]. This constitutes their hidden political significance.”Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” Second Version [1936], in Walter Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 3, 1935-1938 (Harvard University Press, 2002), pp. 101-133. This genre flourished in documentary practice after the Second World War, when on one hand, it set the spotlight on the scale of the destruction, and on the other, on the rapid post-war transformation fueled by the Cold War military drive. Photographs of the cities where the war occurred and the wishful thinking about the future visibly overlapped and forcefully unveiled the process of post-war transformation.The online archive of Life magazine enables an easy access to the photographs from this period taken by world-known photojournalists. See: Nevada Ghosts: Rare Photos from an A-Bomb Test (1955) http://life.time.com/history/atomic-testing-photos-life-magazine/#6, or Brutal Divide: The Birth of the Berlin Wall (1961) http://life.time.com/history/berlin-wall-photos-early-days-of-the-cold-war/#15 Asignificant contribution to the recording of post-war landscapes is a series of untitled photographs by Elzbieta Tejchman (b. 1934), taken during the First Biennale of Spatial Forms in Elblang in 1965. Her work is a little-known example of this genre, both in Poland and internationally. Yet, her powerful depiction of Elblang at this particular historical moment urges serious consideration.

Tejchman’s landscapes are an extraordinary study of spatial and temporal features of abstract sculptures created during the Biennale against the backdrop of the city. The uniqueness of her series results from a powerful juxtaposition of modernity embodied in sculptures with a multilayered history of the city visible in the background. Both subjects characterize each other by contrast and raise awareness of nonlinear history of this particular place. Elblang is located in the Pomeranian district of northern Poland, as the First Partition of Poland in 1772 was Prussian. It was joined to the territories of the Polish People’s Republic after the Second World War. Due to its troubled identity, it was one of the most important targets of socialist propaganda. In this context, the Biennale, through extensive press coverage, became one of major references in the narration concerning post-war development in Poland.

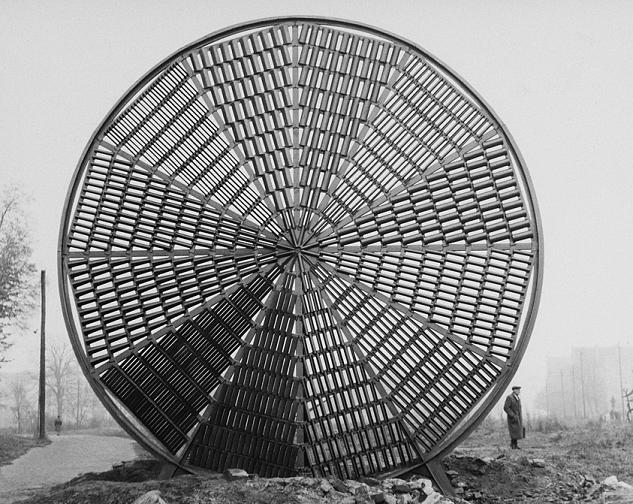

The First Biennale of Spatial Forms is widely recognized as one of the most important artistic events in the post-war history of Poland. It had an unprecedented scale, both in terms of realization, as well as in terms of funding provided by the state. It was the first manifestation of a new idea for state patronage of arts, which subsequently focused on joining art with industry. The Biennale was initiated by Gerard Kwiatkowski, decorator at Zamech Mechanical Works, the local plant of marine equipment, and the manager of Gallery El, established, thanks to his initiative, between 1961 and 1962.Gallery El was one of the most important places where artists and theoreticians gathered between 1965 and 1973. His vision was supported by the plant, patron of the event and provider of the metal scraps used for production of the sculptures. Local approval was followed by state sponsorship, which led to the creation of an event of unprecedented scale. Around forty, mostly Polish avant-garde artists contributed to the Biennale, including Zbigniew Dlubak, Edward Krasi?ski, Henry Sta?ewski and many others. Most of the “spatial forms” they designed were large-scale geometric sculptures that still stand in the city of Elblang today. The notion “spatial form,” appropriated by the Biennale, was first and famously recorded in March 1921 by the inventory of the new museum of contemporary Russian art – the Museum of Painterly Culture / Muzei zhivopisnoi kul’tury (MZhK). Its director at the time was Alexander Rodchenko. The term “spatial form” was proposed by Karl Ioganson, Konstantin Konstantinovich Medunetskii, Georgii and Vladimir Stenberg, and Rodchenko himself, when they offered the museum a work for sale. In their eyes, their proposition challenged the traditional definition of sculpture, by taking an interest in space as a matter of abstract spatial forms.M. Gough, The Artist as Producer: Russian Constructivism in Revolution, University of California Press (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London, 2005), p. 66. The exploration of the relationship between sculpture and its surroundings was also of central interest to the event organizers.

Tejchman’s photographic studies explore, in detail, the relationship between space and sculpture, an issue also crucial to the Biennale organizers. Tejchman’s professional background no doubt helped her to be receptive to this issue. Tejchman had a professional education in photography and worked in numerous photography-related institutions of Warsaw, such as Central Agency of Photography (CAF). At the time of the Biennale, she worked as a photographerfor the Institute for the Organization and Mechanization of the Building Industry (JOMB).Elzbieta Tejchman is a member of the Polish Association of Photographers (since 1969). She was a regular contributor to the magazine Fotografia, when its editor in chief was Zbigniew Dlubak. She also worked with multiple photography related institutions in Warsaw, such as the Central Photographic Agency and was a lecturer in photography at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw (1982–1984). She was permitted to go to Elblang to document what she argued to be a particularly important project for the city space. There, her professional experience, plotted with her personal interest in abstract sculpture, which she was developing in her photography for years.According to an unpublished interview conducted by Sylwia Serafinowicz on December 13, 2011. Central to her studies was W?adys?aw Strzemi?ski and Katarzyna Kobro’s theory of construction and perception of abstract sculpture executed in a book Composition of Space. Calculations of Spatial-Temporal Rhythm / Kompozycja przestrzenna. Obliczenia rytmu czaso-przestrzennego (1931).Katarzyna Kobro and W?adys?aw Strzemi?ski both studied in Russia and were engaged in the Russian and Polish avant-garde with the Constructivist provenience gathered around the magazine Blok (1924-1926). They formulated their own theory of Unism in painting and sculpture, which partly criticized the achievements of Constructivism. In 1928, Strzemi?ski published Unism in Painitng/Unizm w malarstwie, followed by Composition of Space, Calculations of Spatio-Temporal Rhythm/Kompozycja przestrzen, Obliczenia rytmu czaso-przestrzennego (1931), written together with Kobro. Here, Kobro and Strzemi?ski proposed not only a new genre of object, but also a new quality of visual experience. They argued that the essential law of sculpture is its unity with the space surrounding it.Katarzyna Kobro, W?adyslaw Strzemi?ski, Composition of Space, Calculations of Spatio-Temporal Rhythm/Kompozycja przestrzen, Obliczenia rytmu czaso-przestrzennego, Biblioteki ‘a.r.’ no 2. , (?ód?, 1931), p. 5. Consequently, they proposed a new model of “spatial form” that would function in space differently than a solid form. In their opinion, traditional sculpture dominated its surroundings instead of co-existing with it in unity. This new model of sculpture, abstract and based on a rhythmical composition of profiles, would exist well-balanced in space. It would also span time. According to Kobro and Strzemi?ski, the viewer must be in movement, circling the sculpture in order to fully gather the variety of visual impressions provided by its different profiles. For them, sculpture is a spatio-temporal phenomenon happening rhythmically in front of the spectator’s eyes, and has the potential to overcome the limitations of the object. They saw the potential of dynamic, process-based work.Also for Oskar Hansen, theoretician of the Open Form, the basic parameter of sculpture is the time one needs to understand its construction. Only a sculpture that provokes the viewer to walk around it in order to understand its structure is a good spatio-temporal composition.

Kobro and Strzemi?ski’s theoretical tract is possibly the most important of Polish books devoted to the perception of abstract sculpture. Although, there is no record of Kobro and Strzemi?ki’s interest in photography itself, a step towards the photographic image of the form seems to result naturally from their analysis of the potential of the visual phenomena that sculpture might generate. It was a natural gesture for Oskar Hansen, Polish architect and theoretician of Finnish birth, author of the Open Form theory (1959) who seems to be sharing Kobro and Strzemi?ski’s views, when it came to understanding the “spatiio-temporality of forms.”O. Hansen, Forma Otwarta, Przeglad Kulturalny, vol 5, no.5, 1959. Also in the 1950s he used photography to show the sculptural potential of his clay preparations. Later on and together with Jerzy Jarnuszkiewicz, he developed a series of exercises for his sculpture students by encouraging them to work with the camera.Oskar Hansen’s photographs of his clay models Bug and Narew (1954) (Fig. 32) and Sun (1955) monumentalized small-scale sculptural forms and brought attention to the play of light and air around them. See: G. Kowalski & M. Sitkowska, (eds.), Rze?biarze fotografuj?. Muzeum Narodowe (Warsaw, 2004). Visual analysis of sculptures undertaken by sculptors themselves had much more influence on Tejchman than the methods of photographing sculptures applied by professional photographers.

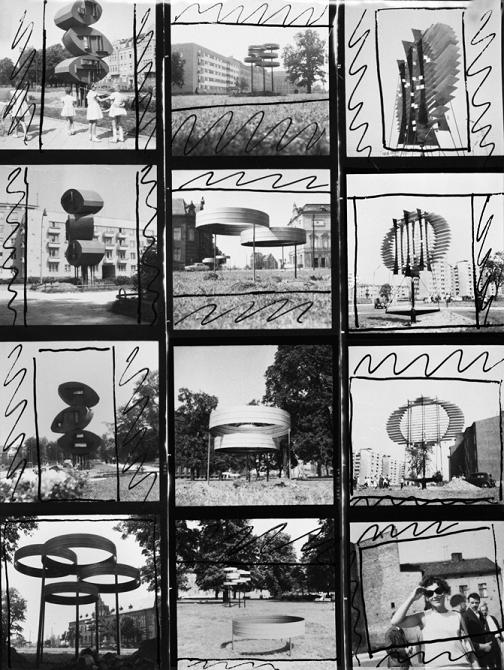

Like Kobro and Strzemi?ski, Tajchman was interested in visual phenomena, which might change with the movement of the viewer. Moreover, she is an attentive observer of sculptural rhythm. She walked around the sculpture not only to capture it from different angles, but basically to see it as a whole. The different visual phenomena experienced by photographer while looking at the sculpture are presented in a series of black-and-white photographs. To capture the changing aspects in chosen sculptures from Elblang, she adapted the method of photographic series. She seems to see the spatial forms in Elblang in a similar vein as Kobro, Strzemi?ski, and Hansen.

Like Kobro and Strzemi?ski, Tajchman was interested in visual phenomena, which might change with the movement of the viewer. Moreover, she is an attentive observer of sculptural rhythm. She walked around the sculpture not only to capture it from different angles, but basically to see it as a whole. The different visual phenomena experienced by photographer while looking at the sculpture are presented in a series of black-and-white photographs. To capture the changing aspects in chosen sculptures from Elblang, she adapted the method of photographic series. She seems to see the spatial forms in Elblang in a similar vein as Kobro, Strzemi?ski, and Hansen.

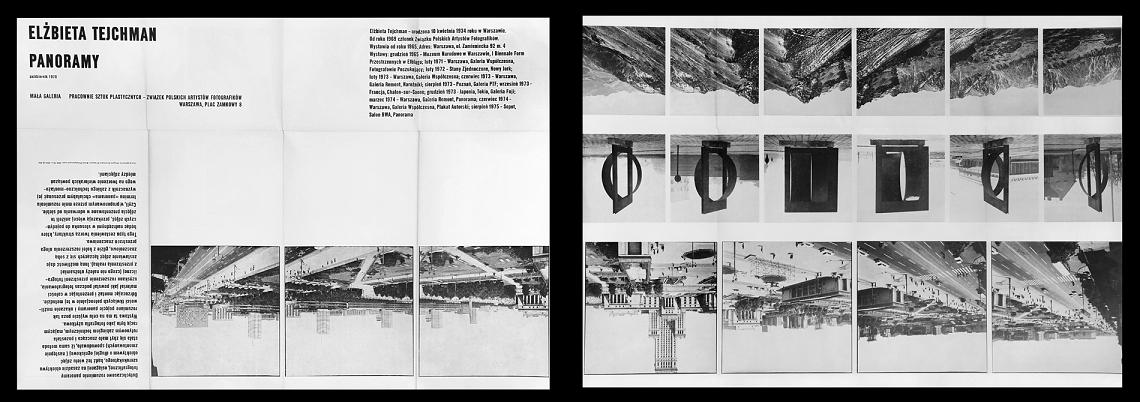

Perhaps the most carefully considered sculptures in Tejchman’s reportage is one by Zbigniew Dlubak, constructed from two, thick metal sheets grounded side by side. Tejchman captures it in a series of “panoramas” that also included the park setting where the sculpture was sited. She captures this “spatial form” in a series of close-ups, some of which suggest that the form is rather slim, while others reveal the true scale of the large metal sheets. Capturing the optical illusion created by the overlap of the two parts of the sculpture was of utmost importance to Tejchman. Some of her photographs record how the two elements meet in the upper part of the form. In other photographs, the two metal sheets meet in the middle and separate again towards the top. Crucial to Tejchman’s photographs of these forms is their serialization, highlighted in her exhibition Panoramas in 1978 at the Ma?a Gallery, Warsaw.In original: Panoramy.

Perhaps the most carefully considered sculptures in Tejchman’s reportage is one by Zbigniew Dlubak, constructed from two, thick metal sheets grounded side by side. Tejchman captures it in a series of “panoramas” that also included the park setting where the sculpture was sited. She captures this “spatial form” in a series of close-ups, some of which suggest that the form is rather slim, while others reveal the true scale of the large metal sheets. Capturing the optical illusion created by the overlap of the two parts of the sculpture was of utmost importance to Tejchman. Some of her photographs record how the two elements meet in the upper part of the form. In other photographs, the two metal sheets meet in the middle and separate again towards the top. Crucial to Tejchman’s photographs of these forms is their serialization, highlighted in her exhibition Panoramas in 1978 at the Ma?a Gallery, Warsaw.In original: Panoramy.

There, she proposes a new reading of a purely technical term “panorama” to express its potential of association between multiple images and, therefore, multiple meanings. Within Tejchman’s choice of words reverberates the personal conviction that a photograph does not mirror the thing or the situation that is photographed. Instead, it captures one of many possible views.Elzbieta Tejchman: Panoramy, exhibition brochure, Ma?a Galeria (Warsaw, 1978). As in Kobro and Strzemi?ski’s theory only through a juxtaposition of many images of the same phenomena can one become aware of its features.

Depicted in the exhibition brochure is the series documenting Zbigniew Gostomski’s Polish artists, reproduced between a series of photographs of Jerozolimskie Avenue in Warsaw and one documenting ?winica (the mountain whose highest summit marks the border between the Polish and Slovak Tatra Mountains).

Tejchman’s collection of depictions of various visual impressions provoked by just one sculpture suggests how the forms are oversimplified when shown in, for example, one frontal shot or as a closely cropped image. Moreover, because Tejchman captured the sculptures during the changing seasons between summer and winter, her photographs not only depict the ephemeral process of their creation and the “visual intrigue around them,” but also show their duration in the meaningful setting of the city of Elblang.

Her photographs show the extensive meadows surrounding the “spatial forms.” Grass covers the ground of the old town destroyed during the Second World War in 1965; these meadows still determine the landscape of Elblang, as we can reason from Tejchman’s reportage. They are so vivid and contrast with the metal industrial forms in the photographs because Tejchman took the photographs when the sites were deserted. In doing so, she focuses the viewer’s attention on the juxtaposition of the pastoral sites with the modern sculptures. She skillfully composes these elements in relation to the layers of the city’s history, which results in photographs that not only capture a particular moment, but also speak about the transformation of Elblag. When asked about her interest in capturing the emptiness of these places, in contrast to other photographers whose images pictured them as crowded, Tejchman responded that she was more interested in the sculptures and architecture than in people. Despite this fact, her images articulate crucial information about the local community. For example, the absence of people from the photograph of Zbigniew Gostomski’s “spatial form” gives a portrait of Elblang during working hours.

Her photographs show the extensive meadows surrounding the “spatial forms.” Grass covers the ground of the old town destroyed during the Second World War in 1965; these meadows still determine the landscape of Elblang, as we can reason from Tejchman’s reportage. They are so vivid and contrast with the metal industrial forms in the photographs because Tejchman took the photographs when the sites were deserted. In doing so, she focuses the viewer’s attention on the juxtaposition of the pastoral sites with the modern sculptures. She skillfully composes these elements in relation to the layers of the city’s history, which results in photographs that not only capture a particular moment, but also speak about the transformation of Elblag. When asked about her interest in capturing the emptiness of these places, in contrast to other photographers whose images pictured them as crowded, Tejchman responded that she was more interested in the sculptures and architecture than in people. Despite this fact, her images articulate crucial information about the local community. For example, the absence of people from the photograph of Zbigniew Gostomski’s “spatial form” gives a portrait of Elblang during working hours.

Tejchman’s photographs respond to the rhythms of work as dictated by the schools and Zamech Mechanical Work, which subordinated the local life. The photograph makes the viewer aware how unusual it would be to see people wandering around a smallcity like Elblag during work time, as citizens were supposed to be either at school or at work, secured by the Socialist state, therefore the emptiness of the streets captured in the photograph. In the void of the city yet to be built, solitary human figures look vulnerable. Tejchman captures the distant silhouettes of passersby while photographing some of the sculptures. These figures are never engaged in action.According to an unpublished interview conducted by Sylwia Serafinowicz on December 13, 2011. As Tejchman monumentalizes the “spatial forms,” they become even more ephemeral, as can be seen in the photograph of Antoni Starczewski’s sculpture.

The print shows a circular metal form placed on the ground exposing what seem to be bricks. The sculpture fills the center of the frame, and leaves only the margins for the vanishing figure of a woman on the right, and the silhouette of a man with a suitcase to the left. In contrast to the reproduction of this photograph in the catalogue of the Biennale, a vintage print of the same photograph shows another “spatial form” (one by Stanis?aw Sikora) in the distance. If we are aware that both sculptures stand next to Gallery El, the host of the Biennale situated in the center of what is today the reconstructed old town, then the void behind Starczewski’s sculpture becomes more than just an ordinary meadow — it is the void caused by the destruction of the old town. Yet another photograph (not reproduced in the catalogue), shows Starczewski’s sculpture from the opposite side. The wide angle also records the nearby buildings and a group of women next to the sculpture. They wear scarves on their heads and have spades in their hands.

It is impossible to know from the image what the purpose of their action might be. The viewer might only guess whether they are cleaning or preparing the ground to plant trees in the meadow. Instead of giving an answer, their presence provokes questions regarding the transformation concerning this setting. The comparison of these archival photographs with the contemporary ones, published in Open Gallery: Spatial Forms in Elblang Guidebook (2006), by other photographers shows us that the meadow between Starczewski’s and Sikorski’s sculptures is today covered with tall trees. Tejchman’s photographs show the city in the laborious process of rebuilding its infrastructure and, more importantly, the formation of a post-war community.The catalogue of the Biennale argued that this was necessary for the integration of the local community. The Biennale was supposed to be a step forward in this process.

Tejchman’s photographs show the past, present and future of Elblang. The past is evoked by the emptiness of the sites of previous war battles. The future of Elblag resides in the everyday efforts of its citizens, who work for their own and their country’s prosperity and, therefore, are absent from the streets between work hours. It is also visible in a collective action of workers of the local metal plant and the visiting artists materializing the urban project of the Biennale. The present is, of course, located somewhere in between, too rapidly changing to be captured in the photographs. Tejchman’s images show the extraordinary potential of photography to speak about social and political processes of transformation. The durational aspect of the abstract sculptures depicted as “spatio-temporal” compositions unfolds against the backdrop of the complex structure of the city of Elblang. Both elements enrich the reading of each other and comprise a photographic practice worthy of further exploration.

Sylwia Serafinowicz is an art critic and a freelance curator. She is currently writing her PhD thesis, More than Documentation: Photography in the Polish People’s Republic Between 1965 and 1981 at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London. She is a Correspondent for Artforum magazine and a member of Ph: The Postgraduate Photography Research Network based in London

Sylwia Serafinowicz is an art critic and a freelance curator. She is currently writing her PhD thesis, More than Documentation: Photography in the Polish People’s Republic Between 1965 and 1981 at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London. She is a Correspondent for Artforum magazine and a member of Ph: The Postgraduate Photography Research Network based in London