Neo Rauch: Neue Rollen, Paintings 1993 to the Present Day

Neo Rauch: Neue Rollen, Paintings 1993 to the Present Day

Galerie Rudolfinum, Prague, October 5-May 8, 2007

Neo Rauch has exhibited widely in recent years and much of the discourse around his paintings hinges on his identity as a product of the DDR, or former communist East Germany. His bizarre pictorial constructions seem to invite a consideration of legacy: of failed socialism and of painting itself. What did/does it all mean? The Kunstmuseum in Wolfsburg Germany has provided an opportunity to reflect on this question by organizing the largest survey of his work to date and sending it on tour to a fitting post-communist location at the Rudolfinum in Prague.

Rauch was born at the height of the cold war in 1960 in Leipzig, East Germany and gained a traditional academic training at the Leipzig Academy of Visual Art. From this environment he created a kind of hallucinogenic socialist realism, where crew-cut workers diligently toiled in absurd environments, rendered in a palette reminiscent of 1960s advertising. It was the model factory married to Star Trek on mushrooms. When his paintings were first shown outside of Leipzig in the mid 1990s, they appeared slightly exotic for a western art audience and coincided with a wave of ostalgie in Germany, or nostalgia for all things related to the East bloc and the retro look of the 60s and 70s. However, what saved his work from being merely fashionable was its lack of sentimentality and his ability to engage the viewer in an active re-interpretation of history painting. The survey of his work in Prague demonstrates this very clearly, and makes apparent that his work succeeds on its own terms as painting and is not entirely contingent on his grappling with a post-communist legacy.

Arguably more important is how he addresses that which is most immediately relevant to a viewer standing in front of one of his canvases: the legacy of painting itself. One of the most obvious facts about seeing Rauch’s paintings in a neo-renaissance architectural setting like the Rudolfinum, is that they look like they belong there. A theoretical walk from a room containing work by Veronese, Titian, and Tintoretto, into a Neo Rauch room would seem perfectly logical. He has utterly absorbed the pictorial language of figurative history painting like few others of his generation; in this respect, his oeuvre is profoundly conservative and seems ready made to satisfy entrenched tastes.

However, hissurreal deployment of traditional language is so oddly enticing that it suggests vitality rather than nostalgic repetition. It also points to the profound appetite that still exists among contemporary viewers for what academic history painting sought to offer up until the nineteenth century when it became so moribund: complex pictorial construction and substantial narrative depth. Jeff Wall helped make the appetite for such things fashionable again among contemporary art audiences with his large scale cibachrome photographs. Neo Rauch satisfies this hunger with paint.

Neo Rauch’s pictorial constructions originate from behind the retina rather than in front, and he exploits the fact that his chosen genre of history painting achieves its correspondence to the real world through extreme artifice. For Rauch, this artifice becomes a kind of psychedelic celebration of paint’s utter malleability and the expansive possibilities of an imagination unrestrained by mediating technologies such as a camera lens. Both the physical malleability of paint and the concurrent fluidity of signification are central to his work.

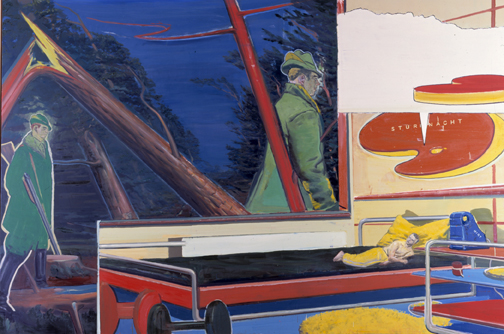

A particularly helpful work in the Prague survey for gaining insight into his practice is “Sturmnacht” (“Stormnight”) from 2000. In it, a tiny doll-like man reclines on an enormous flat bed with a big yellow pillow. A speech balloon shape and two red palettes hover above. Behind, seen through a kind of cutaway window, loom two large gun-toting hunters with feathered German caps. The trees around them are bent and snapped. There is a sense of suspension. The tiny figure, like many of Rauch’s characters, bears more than a passing resemblance to the artist himself. This along with the presence of the palettes, implies an interpretation involving his own professional process; the Teutonic hunter with the shotgun suggests itself as a possible cipher for the scene.

The governing logic is poetic or dreamlike, and Rauch himself has been widely quoted as saying that his paintings are the “continuation of a dream with other means.” However, he is not simply a willfully ambiguous narrator or a latter day surrealist. His self-reflexive use of the medium, both materially in terms of the paint facture with its passages of flat color, scrapings, drips, etc., and his manipulation of genre, is much broader and more ambitious. He introduces familiar elements culled from history painting, mass media, etc. as convincing illusions and snaps them back and forth between the world of make believe and the reality of the flat canvas. Then gravity gives way unexpectedly, our awareness of the picture plane shifts back to deep space, and colors multiply in a profusion of muted tones and brightly acidic hues. In this sense his paintings are not illustrations meant to be decoded, but embodiments of the process of their own appearance.

Wandering from room to room in this survey and seeing the progression from his flatly graphic early painting of the 1990s, to the more fully rendered recent ones, it is apparent that his work has become increasingly traditional. However, this does not imply a retreat into conventional aspirations, but the ambition to subsume and expand them. A lot of contemporary art concerns itself with a self-conscious re-visitation of past modes of art production and ranges from critical commentary to adoring repetition. It is unusual to see an artist engage in the critical side of this process while wholeheartedly inhabiting the forms themselves and utilizing them according to their original criteria.

For Rauch and his chosen idiom of history painting, this means constructing a pictorial scene from scratch, without photographic references, and creating a comprehensive visual universe that utilizes all the tools of composition, color, lighting, modeling, etc. that the old masters themselves would have understand as benchmarks for excellent painting. Put simply, very few contemporary painters possess the technical ambition that the “old masters” took for granted. Rauch does and he is one of the few able to fulfill this ambition and not seem retrograde. He is no Odd Nerdrum. His ability to evoke a sense of wonder and entice the viewer into actively participating in the process of transforming raw oily pigment into compelling imagery is expansive and liberating. The Prague survey demonstrates that this ability, as much as the discourse surrounding his identity as an artist from the former DDR who produces somnambulent musings on failed socialism, is essential when considering “what did/does it all mean?”