Moholy-Nagy: Future Present

MOHOLY-NAGY: FUTURE PRESENT, THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO, OCTOBER 2, 2016-JANUARY 3, 2017

“Art has two faces, the biological and the social, one toward the individual and the other toward the group. By expressing fundamental validities and common problems, art can produce a feeling of coherence. This is its social function which leads to a cultural synthesis as well as to a continuation of human civilization.”

-László Moholy-Nagy (László Moholy-Nagy, Vision in Motion (Chicago: Paul Theobald, 1947), p. 28.)

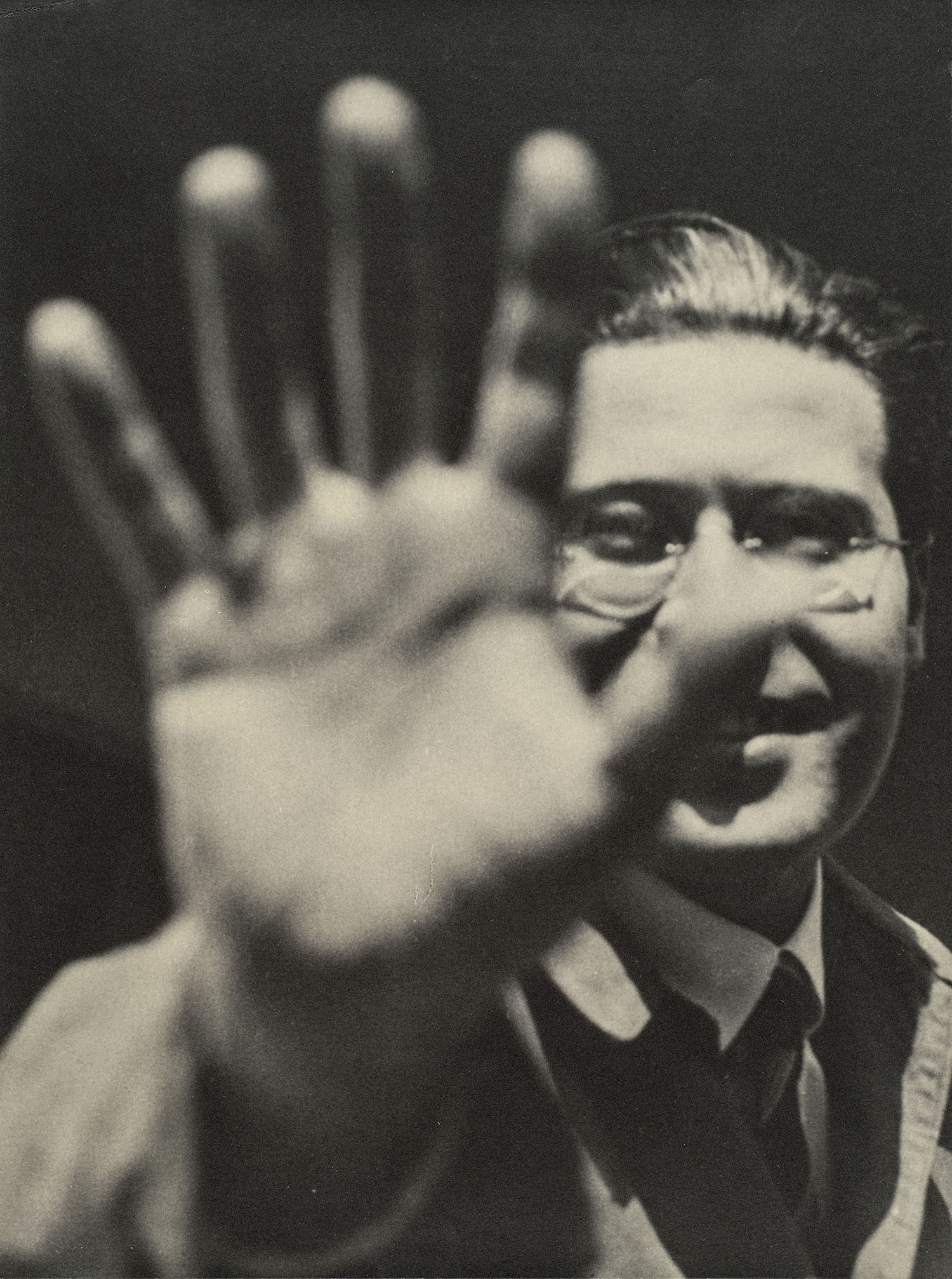

Moholy-Nagy: Future Present, the long overdue traveling retrospective of Hungarian-born artist and educator László Moholy-Nagy, is a timely testament to an artistic practice that was truly interdisciplinary, spanning seemingly every medium and ism, and to an aesthetic vision that saw the creative potential in every citizen. For Moholy, both artist and citizen, armed with the tools of modern technology, would translate the everyday conditions of modern life into a “new vision,” one that would alter the perceptual experience of the individual while materially transforming society. As the exhibition, which opened at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York and ends its tour at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, revealed, with its over 300 works, including painting, photography, film, sculpture, graphics and designed objects, Moholy set his utopic vision into endless action. (Future Present was on view at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, May 27-September 7, 2016, and at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, February 12-June 18, 2017.)

Moholy-Nagy: Future Present, the long overdue traveling retrospective of Hungarian-born artist and educator László Moholy-Nagy, is a timely testament to an artistic practice that was truly interdisciplinary, spanning seemingly every medium and ism, and to an aesthetic vision that saw the creative potential in every citizen. For Moholy, both artist and citizen, armed with the tools of modern technology, would translate the everyday conditions of modern life into a “new vision,” one that would alter the perceptual experience of the individual while materially transforming society. As the exhibition, which opened at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York and ends its tour at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, revealed, with its over 300 works, including painting, photography, film, sculpture, graphics and designed objects, Moholy set his utopic vision into endless action. (Future Present was on view at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, May 27-September 7, 2016, and at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, February 12-June 18, 2017.)

The earliest works in the exhibition date to around 1919/1920, when Moholy, largely self-taught, began his career as an artist while recovering from injuries sustained as a soldier during the First World War. The artist’s unwavering belief in abstraction as the new language of visual representation is established early on, from his interest in simultaneity (for example, Cubist Cityscape, circa 1920-21), a concept manifested throughout his career, to his fascination with the modern industrial landscape.

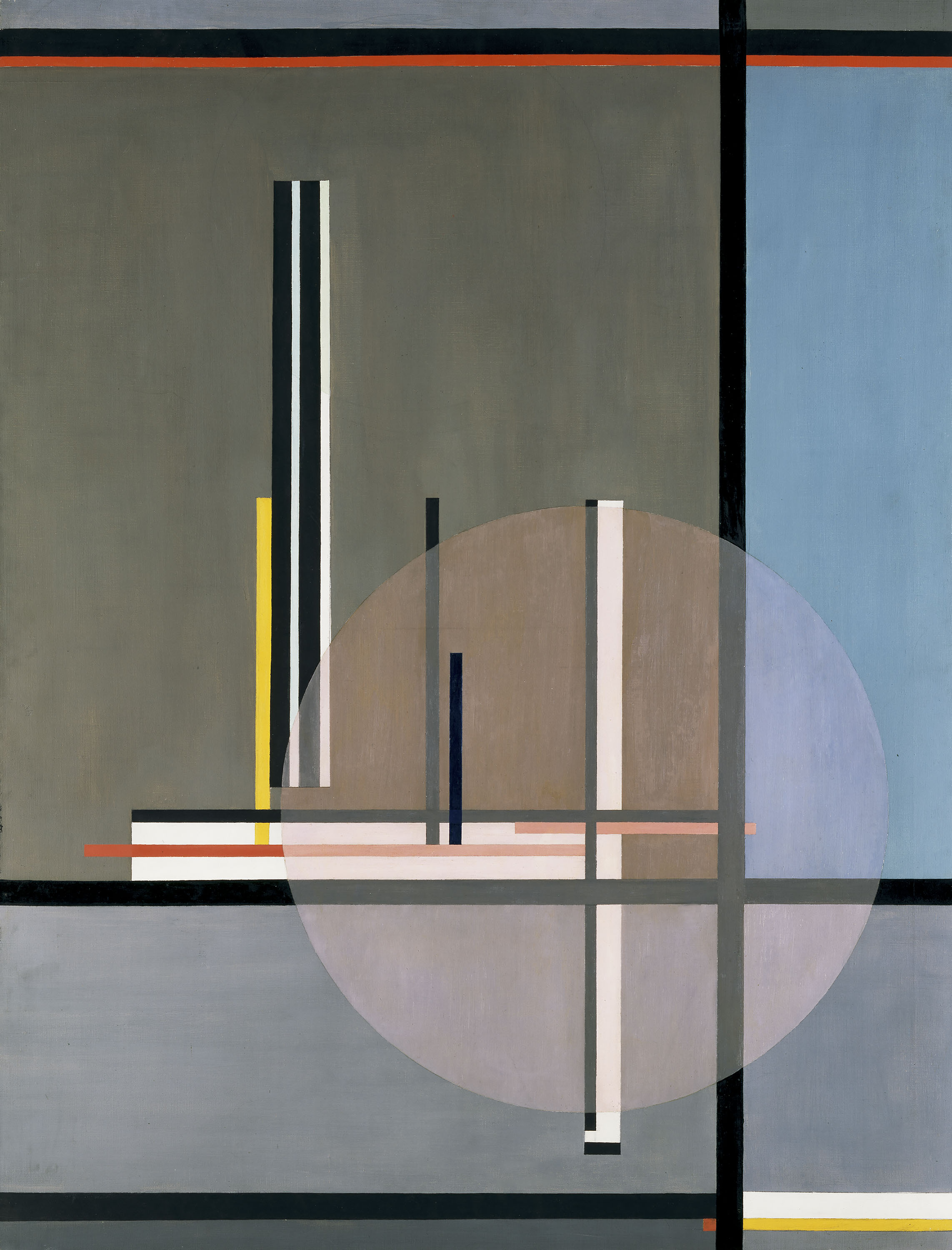

Moholy aligned himself with the Constructivists, particularly El Lissitzky, as evinced in several compositions or “constructions,” in which bridges, wheels, railways and radio towers are rendered in a bold, elemental geometry of mainly primary colors to evoke the progressive dynamism of the industrial age. These architectural referents soon give way to a more subjective language of nonobjective forms that intersect within either spare canvas or paper grounds. Their titles are written in a system of alphanumerics, combining letters and numerals, such as A 19 (c. 1927) and K VII (1922), to suggest a kind of technological or mechanical code rather than the linguistic plays commonly employed by the Dadaists, who were also influential to the artist and whose imprint is found in some of Moholy’s early collages, photomontages and graphic designs for MA (Today), the publication of the Hungarian avant-garde group of the same name to which the artist belonged.

Moholy aligned himself with the Constructivists, particularly El Lissitzky, as evinced in several compositions or “constructions,” in which bridges, wheels, railways and radio towers are rendered in a bold, elemental geometry of mainly primary colors to evoke the progressive dynamism of the industrial age. These architectural referents soon give way to a more subjective language of nonobjective forms that intersect within either spare canvas or paper grounds. Their titles are written in a system of alphanumerics, combining letters and numerals, such as A 19 (c. 1927) and K VII (1922), to suggest a kind of technological or mechanical code rather than the linguistic plays commonly employed by the Dadaists, who were also influential to the artist and whose imprint is found in some of Moholy’s early collages, photomontages and graphic designs for MA (Today), the publication of the Hungarian avant-garde group of the same name to which the artist belonged.

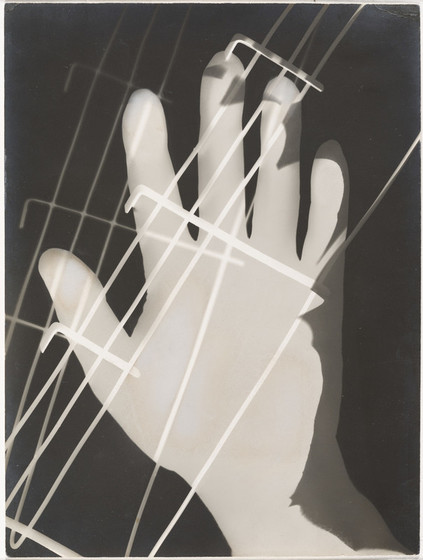

Two of the alphanumeric paintings (both 1924) executed in a reductive palette of black, white and gray oils and graphite seem to anticipate Moholy’s photographic abstractions or photograms, a term the artist coined in 1925 for cameraless images created by placing objects onto photosensitive paper. The result is a black-and-white field of solids and voids that disrupts photographic conventions, as representation gives way to the optical and expressive potentials of light. In several works, ghostly shapes materialize/dematerialize as stark interplays of shadow and light, creating abstract motifs similar to those that inhabit his paintings. Elsewhere, Moholy used his own body, placing his hand or cheek onto sensitized paper, a gesture that denotes the artist as both author and disembodied subject.

With the photograms Moholy begins his lifelong experiments with light as both an artistic medium and as an instrument of production, from his photographs to his kinetic and Plexiglas sculptures to his films. In his 1922 essay “Production-Reproduction,” written the year before Walter Gropius invited Moholy to teach at the Bauhaus in Germany, the artist defines art in terms of “creative production” versus reproduction. For Moholy, creative production enlisted new technologies, here the phonograph, photography and film, to create “unknown relationships” between external reality and the senses instead of the replication or reproduction of existing ones. “This accounts for the permanent necessity of new experiments,” declared Moholy. (Excerpted in Krisztina Passuth, Moholy-Nagy (NY: Thames and Hudson, 1985), p. 289.)

With the photograms Moholy begins his lifelong experiments with light as both an artistic medium and as an instrument of production, from his photographs to his kinetic and Plexiglas sculptures to his films. In his 1922 essay “Production-Reproduction,” written the year before Walter Gropius invited Moholy to teach at the Bauhaus in Germany, the artist defines art in terms of “creative production” versus reproduction. For Moholy, creative production enlisted new technologies, here the phonograph, photography and film, to create “unknown relationships” between external reality and the senses instead of the replication or reproduction of existing ones. “This accounts for the permanent necessity of new experiments,” declared Moholy. (Excerpted in Krisztina Passuth, Moholy-Nagy (NY: Thames and Hudson, 1985), p. 289.)

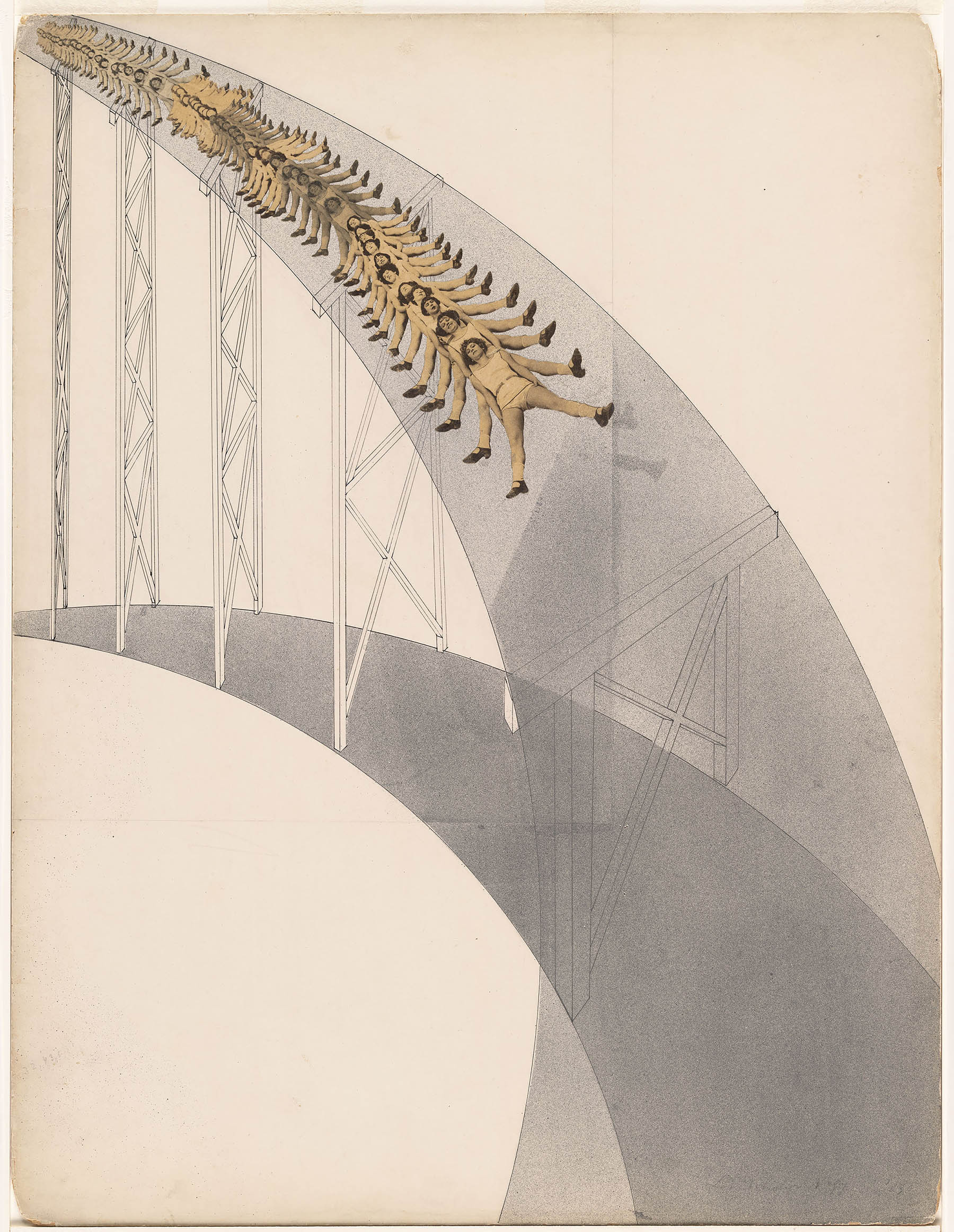

Future Present embodies this experimentation and is a celebration of the artist’s tireless commitment to creative production, one that unfolded chronologically throughout the Art Institute’s spacious galleries in a lively progression in keeping with Moholy’s work. Individual rooms devoted to, for example, his photomontages, with their humorous images of athletes, circus acrobats, and occasional soldiers, and to his design work while teaching at the Bauhaus (1923-1928) attest to the fluidity by which he worked across media and between his roles as an artist, designer and pedagogue. Nowhere was this more evident than in a special gallery housing a recreation of Moholy’s Room of the Present, a multimedia environment commissioned in 1930 but never realized. Part installation, part exhibition, the space is filled with everyday objects, films and photographic images documenting new designs for modern living in tandem with the artist’s own work, including his kinetic Light Prop for an Electric Stage (1930), whose movement and optical effects were emblematic of Moholy’s “new vision.”

Future Present embodies this experimentation and is a celebration of the artist’s tireless commitment to creative production, one that unfolded chronologically throughout the Art Institute’s spacious galleries in a lively progression in keeping with Moholy’s work. Individual rooms devoted to, for example, his photomontages, with their humorous images of athletes, circus acrobats, and occasional soldiers, and to his design work while teaching at the Bauhaus (1923-1928) attest to the fluidity by which he worked across media and between his roles as an artist, designer and pedagogue. Nowhere was this more evident than in a special gallery housing a recreation of Moholy’s Room of the Present, a multimedia environment commissioned in 1930 but never realized. Part installation, part exhibition, the space is filled with everyday objects, films and photographic images documenting new designs for modern living in tandem with the artist’s own work, including his kinetic Light Prop for an Electric Stage (1930), whose movement and optical effects were emblematic of Moholy’s “new vision.”

However Moholy never abandoned his interest in painting and the exhibition does well in illuminating how his use of new technologies fueled new possibilities for painting, which the artist saw as liberated from the burden of representation. This included the use of industrial materials such as aluminum and synthetic plastics as supports, and incising or perforating the surface to create the shadows and textures achieved in his photograms. Likewise, the artist brought his ongoing exploration of the relationship between the handmade and the machine, between individual authorship and collective creation, to painting as early as 1923 with his Construction in Enamel series, more commonly known as the Telephone Pictures. The three works included here (reunited for this exhibition) are three versions of the same abstract composition in three different sizes that the artist ordered from an enamel sign company over the telephone. The formal and conceptual tenets behind these works, with their pared-down geometry, serial format, and use of industrial materials and telecommunications, foreshadow 1960’s Minimalism and Conceptual Art. As Moholy noted: “Thus, these pictures did not have the virtue of the ‘individual touch,’ but my action was directly against this overemphasis. I often hear the criticism that because of this want of the individual touch, my pictures are ‘intellectual.’” (The artist quoted in Louis Kaplan, László Moholy-Nagy: Biographical Writings (Durham & London: Duke University Press, 1995), pp. 121-22.)

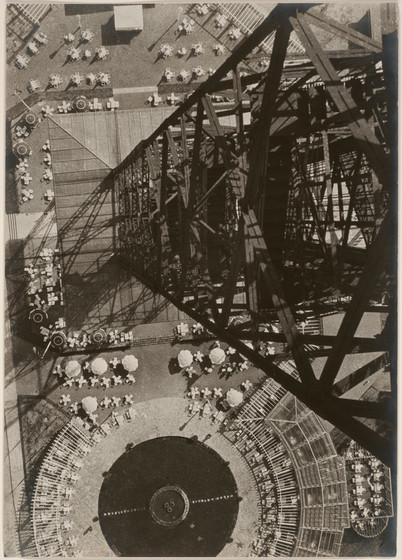

In his essay for the exhibition catalog, Olivier Lugon emphasizes that Moholy also brought this concept of “anonymous production” to his photography (and I would also argue to his films), “which he structured around documentary, scientific, journalistic, and amateur practices.”(Olivier Lugon, “The Old Bridge, the Historian, and the New Photographer,” in Moholy-Nagy: Future Present (Chicago: the Art Institute of Chicago, 2016), p. 114.) We witness this in the artist’s frequent use of extreme close-ups, off-kilter perspectives and bird’s-eye views to capture the vernacular of the everyday, whether the patterned play of a fence on a sunlit afternoon or the architectural brawn of the modern city. His well-known vertical views taken from atop the Berlin Radio Tower, a series of six gelatin silver prints from 1928/29 on view together for the first time, leave the viewer with a dizzying vertigo. Eight films screened continuously within a darkened gallery of the exhibition reveal similar subjects and similar kinds of visual experimentation, including abstraction, while also pointing to the artist as a social documentarian, as witnessed in such films as Berlin Still Life (1936), Impressions of the Old Marseille Harbor (1929/31), and Metropolitan Gypsies (1932).

Eight films screened continuously within a darkened gallery of the exhibition reveal similar subjects and similar kinds of visual experimentation, including abstraction, while also pointing to the artist as a social documentarian, as witnessed in such films as Berlin Still Life (1936), Impressions of the Old Marseille Harbor (1929/31), and Metropolitan Gypsies (1932).

Moholy fled Germany in 1933 for the Netherlands then London before coming to Chicago in 1937 at the invitation of industrialist Walter Paepcke to head a new school of design or what was originally known as the New Bauhaus. The second half of the exhibition focuses on, in addition to Moholy’s later artworks, the artist’s industrial design and graphics (posters, advertisements, price tags) and his time as director of the New Bauhaus, later the Institute of Design. While based on the foundational tenets of the original Bauhaus, Moholy adapted its curriculum to the new conditions of the American Midwest, integrating art, science and technology in the service of industry (and by extension society) and to educating the whole individual. (See Elizabeth Siegel, “The Modern Artist’s New Tools,” in Future Present, pp. 223-33.) Although not represented within the exhibition, this vision was challenged throughout his tenure (1937-1946), both politically and economically particularly during the war years, prompting Moholy to refocus the curriculum to support the war effort with workshops devoted to camouflage, veteran rehabilitation, and the development of wooden springs.

Exclusive to the Chicago presentation of Future Present was a special gallery devoted to student work from the New Bauhaus made under Moholy’s tutelage, such as photograms used as classroom aids to study diverse material properties and wood hand sculptures to enhance student understanding of sensory experience. Despite these additions, which also included a large wall graphic outlining the artist’s central pedagogical ideas, this part of the exhibition does not succeed as well as elsewhere in presenting the great diversity of experimentation that occurred at the New Bauhaus, opting instead to highlight the formal connections between student production and the artist’s own work. (Yet to the Art Institute’s credit, the photographic legacy of the New Bauhaus was well documented in the 2002 traveling exhibition Taken by Design: Photographs from the Institute of Design, 1937-1971). Missing too are the innovative display formats that were so central to New Bauhaus exhibitions, which emphasized process over production, and that one experiences in Moholy’s own exhibition designs, including Room of the Present.

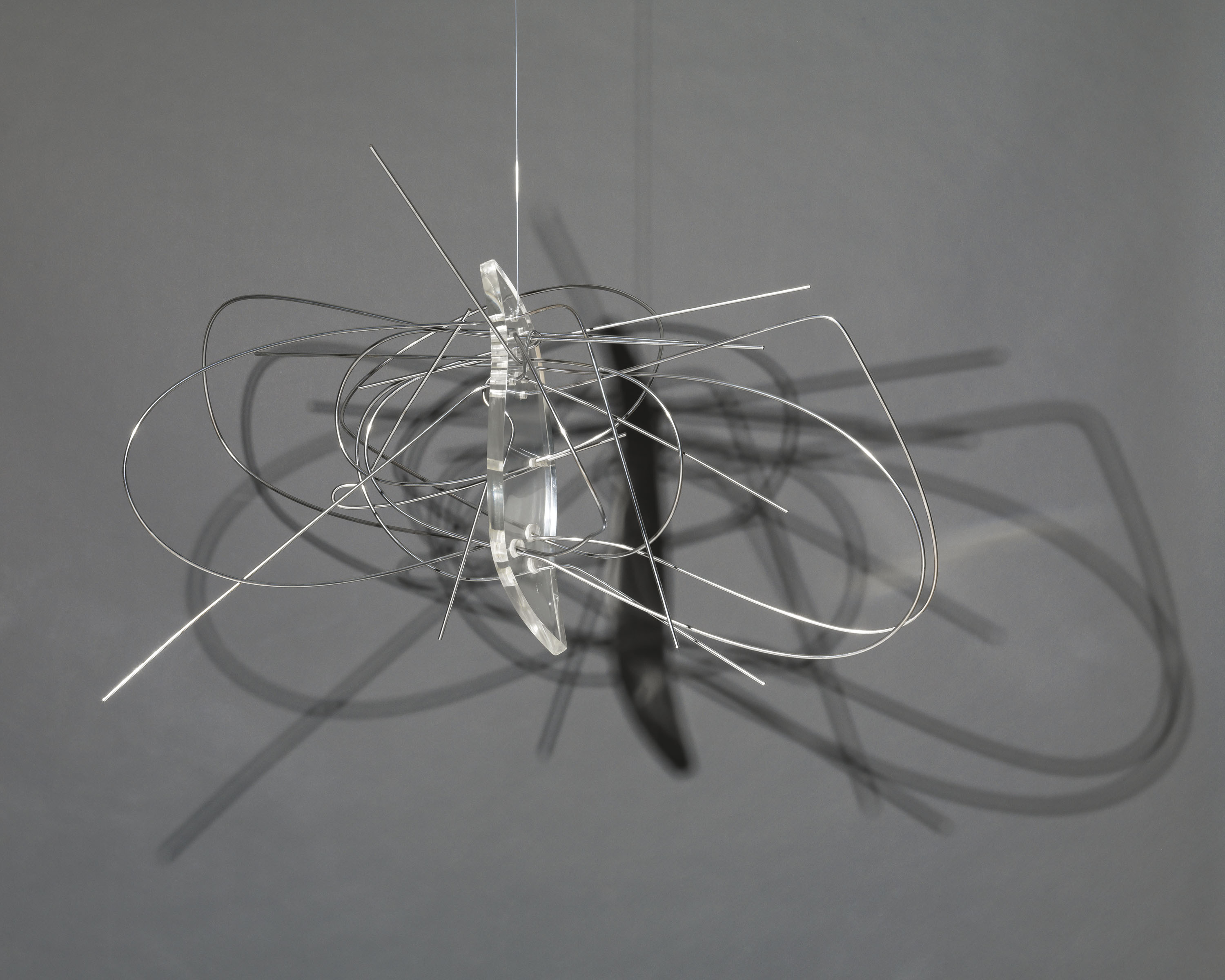

In many ways, Future Present ends full circle: with the artist’s investigations into the transformative potentials of abstraction and light. His final paintings take on a decidedly more biomorphic quality; the exhibition equates their spherical forms with both nuclear and human cells, as a reference to the artist’s own leukemia, to which he succumbed in 1946. Ample space is given to the artist’s Plexiglas sculptures, many suspended from the ceiling and dramatically lit to emphasize their material translucency and dances of shadow and light that occupied him throughout his career.

leukemia, to which he succumbed in 1946. Ample space is given to the artist’s Plexiglas sculptures, many suspended from the ceiling and dramatically lit to emphasize their material translucency and dances of shadow and light that occupied him throughout his career.

Moholy’s belief in art as a transdisciplinary practice and as a “stimuli for the rejuvenation of creative citizenship” operates throughout the exhibition. (Moholy-Nagy from Vision in Motion, as quoted in Future Present, p. 295.) Future Present not only confirms the artist’s many contributions to modernism, but also and as the title suggests, reveals how his “new vision” presages our current cultural epoch.