Mladen Miljanović: At the Edge

Mladen Miljanovi?: At the Edge, acb Gallery, Budapest, June 6 – July 17, 2014

At the beginning of his career, Bosnian artist Mladen Miljanovi? prepared ironically toned, but rather serious, plans of attack (Artattack series, 2007) for occupying the great museums of the world. Actually, he painted military symbols on the maps of contemporary art museums and galleries representing how he could occupy their spaces. Of his targets, ironically, Budapest was the last “captured” city, as the artist showcased works in the exhibition spaces of New York, London and Venice before showing in the contemporary art institutions of neighboring Hungary. While an overview of the underlying cultural and geopolitical factors surrounding this would lead beyond the scope of this review, it is worth pointing out that the works of Miljanovi?, one of the stars of the 2013 Venice Biennale, once again enriched the “portfolio” of a private gallery rather than strengthening the profile of a state financed institution. Tijana Stepanovic, curator of the artist’s recent solo exhibition at acb Gallery, Budapest, perhaps wished to reflect on this situation by titling the show At the Edge. Current cultural policy in Hungary, through the withdrawal of state funding, is increasingly pushing aesthetically progressive and politically committed (meaning left-wing and critical) art to the periphery, resulting in its near disappearance from the larger exhibition spaces of Budapest in the last few years. In addition, sober, unbiased, and deconstructive interpretations of the communist and post-communist periods have also been struck from the agenda of Hungary’s major state institutions. For these reasons, Miljanovi?’s art, and the show at acb, are doubly exciting for today’s Budapest. Not only does it reflect on the culture and politics of the communist and post-communist past, it does so in the markedly nationalist climate of the present-day Bosnian Serb Republic.

In addition to focusing on new geographical and historical boundaries, both At the Edge and Miljanovi?’s art, in general, guide us to metaphysical and existential domains. The eponymous work included in this exhibition approaches one of the most renowned topoi of avant-garde art – the reunification of life and art – with a sense of irony that is almost heroic.(Peter Bürger: Theorie der Avant-Garde, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main, 1974.) At the Edge (2008- ) is also the title of an ongoing performance series Miljanovi? executes in the buildings of galleries he has “seized.” In this series, the artist seeks out a place (e.g. a window or a balcony), where he literally extends – or “hangs” – from the building of the museum or gallery; in other words, he suspends himself from the “sacral” and autonomous spaces of art into the profane spaces of everyday life. Miljanovi? suspends himself for as long as he can, exposing his body and demonstrating his physical abilities to the public. (Note that prior to becoming a professional artist, he attended a military training school.)

The earliest document bearing traces of the physical skill and heroism that are also apparent in the At the Edge performance series is I Serve Art (2006-2007), one of the most important and geopolitically relevant works showcased in the Budapest exhibition. This piece puts a very concrete location to the local and existential context of Miljanovi?’s heroic irony – the Academy of Arts Banja Luka, Bosnia-Herzegovina, housed in the building of the former military barracks, where the artist previously served as a soldier. What makes this situation evenmore exceptional is the fact that Miljanovi? once trained to become a professional soldier, then left his career in the military for art, only to find himself back in the place where he had served his country as a soldier. I Serve Art is, in essence, the documentation of a nine-month-long performance, whereby Miljanovi? confined himself in the former military barracks for 274 days. Each day, he took a photo of himself on barracks grounds, gazing outward as a prisoner of his art and his freely chosen new, private life. Moreover, the photos always depict him from behind, standing at attention, while he controls the camera using a self-timer, as if to discipline and condition himself – a soldier of art.

The earliest document bearing traces of the physical skill and heroism that are also apparent in the At the Edge performance series is I Serve Art (2006-2007), one of the most important and geopolitically relevant works showcased in the Budapest exhibition. This piece puts a very concrete location to the local and existential context of Miljanovi?’s heroic irony – the Academy of Arts Banja Luka, Bosnia-Herzegovina, housed in the building of the former military barracks, where the artist previously served as a soldier. What makes this situation evenmore exceptional is the fact that Miljanovi? once trained to become a professional soldier, then left his career in the military for art, only to find himself back in the place where he had served his country as a soldier. I Serve Art is, in essence, the documentation of a nine-month-long performance, whereby Miljanovi? confined himself in the former military barracks for 274 days. Each day, he took a photo of himself on barracks grounds, gazing outward as a prisoner of his art and his freely chosen new, private life. Moreover, the photos always depict him from behind, standing at attention, while he controls the camera using a self-timer, as if to discipline and condition himself – a soldier of art.

Later in his career, it was precisely this ironic, pseudo-militant outlook that became the distinctive guiding thread of his work, as attested to by the aforementioned Artattack series, and by the work Oath to Independent Art (2008), an artist’s manifesto-like text modelled after a military oath. The film Do You Intend to Lie to Me? (2011) – which documents the capture and interrogation of Miljanovi?’s mentor and teacher, Veso Sovilj, and showcased in the Budapest show – might also be interpreted in this context. However, the work is more than a mere recording of a military action, as the artist composes his work in accordance with the Freudian structural model of the psyche. The first part (Superego) is a lyrical homage to the oeuvre of Sovilj, the artist, with flashing images of the journey that leads from his home village to Banja Luka; the second part (Ego) represents current, everyday reality with the capture of Sovilj; the third part (Id) leads to the world of the unconscious through the artist’s interrogation by a lie detector.

Later in his career, it was precisely this ironic, pseudo-militant outlook that became the distinctive guiding thread of his work, as attested to by the aforementioned Artattack series, and by the work Oath to Independent Art (2008), an artist’s manifesto-like text modelled after a military oath. The film Do You Intend to Lie to Me? (2011) – which documents the capture and interrogation of Miljanovi?’s mentor and teacher, Veso Sovilj, and showcased in the Budapest show – might also be interpreted in this context. However, the work is more than a mere recording of a military action, as the artist composes his work in accordance with the Freudian structural model of the psyche. The first part (Superego) is a lyrical homage to the oeuvre of Sovilj, the artist, with flashing images of the journey that leads from his home village to Banja Luka; the second part (Ego) represents current, everyday reality with the capture of Sovilj; the third part (Id) leads to the world of the unconscious through the artist’s interrogation by a lie detector.

Rather than expressly operating in the psychological-philosophical range of interpretation, however, Do You Intend to Lie to Me? exerts its effect through a hybridization of reality and fiction, calling to mind the reality shows of the postmodern media. Furthermore, the film also offers a fascinating and paradoxical amalgamation of the military and artistic fields of interpretation, by confronting two different concepts of heroism: military (active offense) and civilian (passive resistance). After lengthy negotiations, Miljanovi? was able to get the special unit of the Bosnian Serb police to hunt down and apprehend the unsuspecting Sovilj, creating the illusion of a military action against a war criminal. The film not only captures the precision and brutal effectiveness of the special unit, but also the artist’s presence of mind and human composure, as he silently and unflinchingly endures being forced into a car and transported to the police center. These two seemingly different types of heroism come into contrast most strikingly when the interrogating officer asks the artist, undergoing a polygraph test, whether he has ever been in contact with Ratko Mladi?, the infamous Bosnian Serb general, or “Butcher of the Balkans,” convicted of war crimes and responsible for the “ethnic cleansing” in Srebrenica, or whether he knows Ješa Denegri, a renowned Serbian art historian and prominent scholar of avant-garde art. Rather than dwelling on Sovilj’s supposed involvement in the war, the questions that follow center on his thoughts on art and whether he believes in its avant-garde mission and power. It was supposedly at this point in the film that the artist became suspicious that his ordeal was not about his alleged war crimes, but something entirely different.

Rather than expressly operating in the psychological-philosophical range of interpretation, however, Do You Intend to Lie to Me? exerts its effect through a hybridization of reality and fiction, calling to mind the reality shows of the postmodern media. Furthermore, the film also offers a fascinating and paradoxical amalgamation of the military and artistic fields of interpretation, by confronting two different concepts of heroism: military (active offense) and civilian (passive resistance). After lengthy negotiations, Miljanovi? was able to get the special unit of the Bosnian Serb police to hunt down and apprehend the unsuspecting Sovilj, creating the illusion of a military action against a war criminal. The film not only captures the precision and brutal effectiveness of the special unit, but also the artist’s presence of mind and human composure, as he silently and unflinchingly endures being forced into a car and transported to the police center. These two seemingly different types of heroism come into contrast most strikingly when the interrogating officer asks the artist, undergoing a polygraph test, whether he has ever been in contact with Ratko Mladi?, the infamous Bosnian Serb general, or “Butcher of the Balkans,” convicted of war crimes and responsible for the “ethnic cleansing” in Srebrenica, or whether he knows Ješa Denegri, a renowned Serbian art historian and prominent scholar of avant-garde art. Rather than dwelling on Sovilj’s supposed involvement in the war, the questions that follow center on his thoughts on art and whether he believes in its avant-garde mission and power. It was supposedly at this point in the film that the artist became suspicious that his ordeal was not about his alleged war crimes, but something entirely different.

In Budapest, We Love Freedom of Form (2010) examines another aspect of the autonomy of art (which is simultaneously doubtful and dangerous), and can, in fact, be considered an activist manifesto, as it is precisely the modern aesthetic autonomy of art that it speaks out against, albeit ironically, when the artist proclaims in his pseudo, socialist realist text engraved on a granite slab: “We Love Freedom of Form As Long As That Freedom is Within Form.” The irony of the work is rather multi-layered as the realist, reflective function of modern art is here represented by the rearview mirror of a Zastava car, which points neither towards avant-garde universality nor to the aesthetic laws of art, but towards the everyday dimensions of life. The text, again engraved on a black slab of granite, leads back to the symbolism and visual culture of gravestones. In this way, it could be the epitaph of the kind of art that reflects reality but is autonomous. This epitaph, however, is engraved with anamorphically distorted letters and can only be read through the mirror of the Zastava car. All this suggests that the aesthetic and political failure of autonomous art that has been buried can only become obvious in the metaphorical mirror of everyday life, and only if the viewer is aided in this recognition by a complex apparatus. In Miljanovi?’s interpretation, this complex apparatus is none other than art, which needs to take on the great, universal task of teaching, educating and enlightening people. This mission, in turn, is the same as the well-known program of politically committed, avant-garde art, which Miljanovi? also claims as his own, except that he works with complex postmodern and post-structuralist tools that also take into account the intricacies of consciousness, identity and culture.

In Budapest, We Love Freedom of Form (2010) examines another aspect of the autonomy of art (which is simultaneously doubtful and dangerous), and can, in fact, be considered an activist manifesto, as it is precisely the modern aesthetic autonomy of art that it speaks out against, albeit ironically, when the artist proclaims in his pseudo, socialist realist text engraved on a granite slab: “We Love Freedom of Form As Long As That Freedom is Within Form.” The irony of the work is rather multi-layered as the realist, reflective function of modern art is here represented by the rearview mirror of a Zastava car, which points neither towards avant-garde universality nor to the aesthetic laws of art, but towards the everyday dimensions of life. The text, again engraved on a black slab of granite, leads back to the symbolism and visual culture of gravestones. In this way, it could be the epitaph of the kind of art that reflects reality but is autonomous. This epitaph, however, is engraved with anamorphically distorted letters and can only be read through the mirror of the Zastava car. All this suggests that the aesthetic and political failure of autonomous art that has been buried can only become obvious in the metaphorical mirror of everyday life, and only if the viewer is aided in this recognition by a complex apparatus. In Miljanovi?’s interpretation, this complex apparatus is none other than art, which needs to take on the great, universal task of teaching, educating and enlightening people. This mission, in turn, is the same as the well-known program of politically committed, avant-garde art, which Miljanovi? also claims as his own, except that he works with complex postmodern and post-structuralist tools that also take into account the intricacies of consciousness, identity and culture.

To better contextualize the Budapest show I want to mention two important works not exhibited at acb Gallery. Happening Balkana (2005), one of Miljanovi?’s first works, was also conceived in the above described postmodern and post-communist spirit, notably as an attempt to redraw the traditional, exotic, colonialist image of the Balkans. This happening took the form of a workshop, to which he invited Serbian, Croatian and Bosnian men who had lost one of their limbs in the war to talk about their war experiences and their “civilian” life after it. Miljanovi? not only deconstructed the roles of the aggressor and victim by inviting the soldiers of former enemies, but also attempted to rewrite the boundaries of life and art, of politics and aesthetics, of rehabilitation and participatory art.

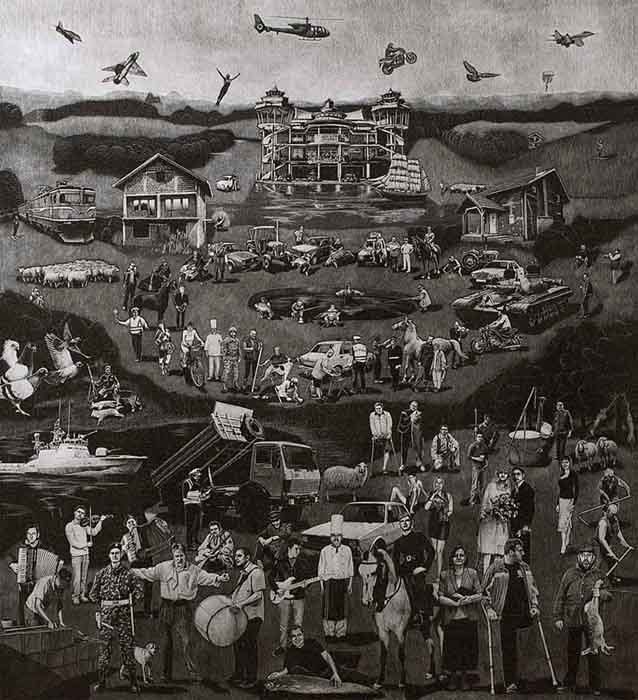

Miljanovi?’s best-known work, The Garden of Delights (2013) – a rather unique paraphrasing of Hieronymus Bosch’s masterpiece, which was presented at the 2013 Venice Biennale but not in Budapest– also shows a similar engagement with the postmodern apparatus and the post-communist spectacle. Bosch created The Garden of Earthly Delights around 1500, at the twilight of the Middle Ages and the dawn of capitalist culture. His masterpiece summed up the religious and moral worldview of the times with a mysterious sense of irony and a humor that still seems cynical today, allowing quite a bit of room for oppressed and condemned desires.(Keith Moxey: “Hieronymus Bosch and the ‘World Upside Down’: The Case of The Garden of Earthly Delights,” in Norman Bryson, Michael Ann Holy, and Keith Moxey (eds.), Visual Culture: Images and Interpretations, Wesleyan UP, Hanover, 1994. pp. 104-140.) The Bosnia-Herzegovina national pavilion at the Biennale constituted one of the last stops in the reception of Bosch’s triptych, pointing to an era that could easily be defined as the twilight of communism, or even modernity – although we are not threatened by a cultural and political shock comparable to the discovery of the New World, or the dawn of anything, for that matter, as capitalism remains the dominant mode of production on Planet Earth. While there may be no foreign civilizations left to discover, this does not mean that we are not subjected to ever newer traumas: the age of wars and genocide is far from over. In what is referred to today as the Bosnia-Herzegovina region, for instance, indescribable horrors took place in the recent past, which have significantly shaped the visual culture of today’s South Slav states.

Miljanovi?’s best-known work, The Garden of Delights (2013) – a rather unique paraphrasing of Hieronymus Bosch’s masterpiece, which was presented at the 2013 Venice Biennale but not in Budapest– also shows a similar engagement with the postmodern apparatus and the post-communist spectacle. Bosch created The Garden of Earthly Delights around 1500, at the twilight of the Middle Ages and the dawn of capitalist culture. His masterpiece summed up the religious and moral worldview of the times with a mysterious sense of irony and a humor that still seems cynical today, allowing quite a bit of room for oppressed and condemned desires.(Keith Moxey: “Hieronymus Bosch and the ‘World Upside Down’: The Case of The Garden of Earthly Delights,” in Norman Bryson, Michael Ann Holy, and Keith Moxey (eds.), Visual Culture: Images and Interpretations, Wesleyan UP, Hanover, 1994. pp. 104-140.) The Bosnia-Herzegovina national pavilion at the Biennale constituted one of the last stops in the reception of Bosch’s triptych, pointing to an era that could easily be defined as the twilight of communism, or even modernity – although we are not threatened by a cultural and political shock comparable to the discovery of the New World, or the dawn of anything, for that matter, as capitalism remains the dominant mode of production on Planet Earth. While there may be no foreign civilizations left to discover, this does not mean that we are not subjected to ever newer traumas: the age of wars and genocide is far from over. In what is referred to today as the Bosnia-Herzegovina region, for instance, indescribable horrors took place in the recent past, which have significantly shaped the visual culture of today’s South Slav states.

Miljanovi?’s work is a spectacular piece, as it closely follows the topography of Bosch’s triptych, with its heavenly and earthly spheres. Its impressive visual appearance is further amplified by the fact that the work, engraved in black granite, is reminiscent of a giant tomb. The spectacular nature of the piece, along with the grotesque humor of the spectacle (the garden of Bosnian delights!), immediately brings to mind the stereotypical image of the Balkans, whose best known visual articulation may be Emir Kusturica’s Palme d’Or-winning film entitled Underground (1995) – which, in fact, was screened shortly before the Srebrenica massacre. It was precisely this Kusturician, deeply rooted, essentially orientalist (garden of delights!) and colonialist image of the Balkans that the war atrocities of the nineties reinforced, further amplifying the violent and demonic connotations of the exotic and sensual Balkans.(Maria Todorova: Imagining the Balkans, Oxford UP, Oxford, 1997. Todorova’s point of departure is, of course, Edward Said’s principle work: Orientalism, Penguin, London, 1977.)

It is the deconstruction of these very stereotypes, however, that is most characteristic of the “Balkan” visual culture of the twenty-first century. Rather than directing his attack at the “imperialist” West, Miljanovi? attempts to deconstruct the image of the brutal and depraved Serbian man, who – in contrast to his Western colleagues – sees members of the local population not just as military and sexual targets, but as keepers of a rather complex culture, whose desires and memories are worthy of articulation through one of the highest art forms of the West – the triptych.(Walter Mignolo: “Epistemic Disobedience and the Decolonial Option: A Manifesto,” Transmodernity (Fall 2011), https://escholarship.org/uc/item/62j3w283#page-1.) What’s more, the artist assumes the function of not only the painter and the engraver, but also the sociologist and the ethnographer, who photographs and collects the hyper-realistic representations that serve as the basis of the triptych from the gravestones of various cemeteries in the Balkans.(Hal Foster: “The Artist as Ethnographer,” in The Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century, MIT Press, Cambridge, 1996, pp. 171-204.)

It is this fieldwork that renders The Garden of Delights a true sepulchre of the former Yugoslavia – a grotesque triptych of ex-Yugoslav notions of earthly happiness, material wealth and power, where the concepts of earthly and heavenly paradise are mixed, and where equestrian portraits, herds and large prey find their place, along with merry, one-legged people, gleaming Zastava cars and destructive tanks. From this vantage point, Miljanovi?’s tableau is not that different from Kusturica’s world after all, just as Venice is not that different from Cannes. It is the carrier and the immediate artistic context – the “gravestone” and Miljanovi?’s consistently “avant-garde” oeuvre – that signifies and creates the immense difference. This culture – of which Miljanovi? is also part with his own desires, goals, and artistic ambitions – is not so much celebrated and mystified by the artist, as it is grieved for and put to rest. Recomendamos nuevo viagra generico sitio? Comprar Viagra genérico en España online. Pide Viagra Genérica en línea sin receta, sin problemas. Nueve ‘genéricos’ compiten en España con la Viagra de Pfizer? Los genéricos de Viagra ya están en las farmacias. Comprar Viagra genérico online en España Viagra Sin Receta barato Viagra precio sin receta en farmacias.¿Qué es Viagra Para Hombres? 5 Lugares de venta de Viagra por internet. Cada día miles de personas compran genéricos de Viagra por internet, ya que es más sencillo y barato.Hable con su médico acerca del tratamiento para la disfunción eréctil.

It is this fieldwork that renders The Garden of Delights a true sepulchre of the former Yugoslavia – a grotesque triptych of ex-Yugoslav notions of earthly happiness, material wealth and power, where the concepts of earthly and heavenly paradise are mixed, and where equestrian portraits, herds and large prey find their place, along with merry, one-legged people, gleaming Zastava cars and destructive tanks. From this vantage point, Miljanovi?’s tableau is not that different from Kusturica’s world after all, just as Venice is not that different from Cannes. It is the carrier and the immediate artistic context – the “gravestone” and Miljanovi?’s consistently “avant-garde” oeuvre – that signifies and creates the immense difference. This culture – of which Miljanovi? is also part with his own desires, goals, and artistic ambitions – is not so much celebrated and mystified by the artist, as it is grieved for and put to rest. Recomendamos nuevo viagra generico sitio? Comprar Viagra genérico en España online. Pide Viagra Genérica en línea sin receta, sin problemas. Nueve ‘genéricos’ compiten en España con la Viagra de Pfizer? Los genéricos de Viagra ya están en las farmacias. Comprar Viagra genérico online en España Viagra Sin Receta barato Viagra precio sin receta en farmacias.¿Qué es Viagra Para Hombres? 5 Lugares de venta de Viagra por internet. Cada día miles de personas compran genéricos de Viagra por internet, ya que es más sencillo y barato.Hable con su médico acerca del tratamiento para la disfunción eréctil.

The complexity of Miljanovi?’s grief work is brilliantly illustrated by the piece Monumental Fragmentation (2010), featured at acb Gallery, which nuances deeply rooted images of the Balkan in a fascinating manner. To be more precise, it deconstructs these images in the most literal sense of the word – and in accordance with the artist’s intentions – through the medium of engraved granite slabs and tombs. On the one hand, it shatters the symbol of Yugoslavian, socialist prosperity (the Zastava), and, on the other, it makes a metaphorical reference to the recent geopolitical disintegration of the former, imaginary nation. As a result of the latter, thanks to Slavoj Žižek, a more modulated, less monolithic image of the Balkans could make its way into Western culture, which draws attention to the uncertainties surrounding the boundaries between West and East, Europe and the Balkans.(Slavoj Žižek: “The Spectre of Balkan,” The Journal of the International Institute (Winter 1999), http://quod.lib.umich.edu/j/jii/4750978.0006.202/–spectre-of-balkan?rgn=main;view=fulltext.) And this is most probably felt by Miljanovi?, living on the “edges” – in the Republika Srpska (Bosnian Serb Republic), along the borders of “civilized” Christian Serbia and “barbarian” Moslem Bosnia.

In Hungary’s current situation of conservative, nationalist cultural politics, Miljanovi?’s post-communist, ex-Yugoslav art is made especially exciting by the fact that it has become part of official, Bosnian Serb national representation, despite the artist’s intentions of wishing to serve neither the state nor its representation, but rather emancipatory, avant-garde art. From a global, rather than local viewpoint, Miljanovi?’s oeuvre is compelling in the way it reflects on Marxist and post-Marxist aesthetics and their topoi. Miljanovi?’s avant-garde, emancipatory artistic mentality did not deter him from employing military and political means. This approach, however, once again points to the old ethical dilemma of life and art, politics and aesthetics: how can we take up the fight against global Capital, against an Empire that is built on a military-industrial foundation – in other words against the mediatized Spectacle – without submitting to it? There is something worth considering here, something illuminating, even piquant. In the aesthetic and political sense, the “Eastern” Miljanovi?, at the gates of “Western” success, follows not the sterile and anti-capitalist example of Alain Badiou (whom the artist has been known to quote), but the Debordian and Rancièreian credo, when he contends that the apparatus and tools of the Spectacle can be employedagainst the global, capital industry of culture and consciousness in an effort to keep the revolutionary entity of avant-garde art – which has been buried, grieved for and recycled so many times – alive.(Miljanovi? engraved in granite an excerpt from one of Alain Badiou’s fifteen theses in the work A Stone Garden (2013) showcased at the Garden of Delights exhibition at the Venice Biennale. “All art, and all thought, is ruined when we accept this permission to consume, to communicate and to enjoy.” Cf.: Alain Badiou, “Fifteen Theses on Contemporary Art,” Lacanian Ink (2003), http://www.lacan.com/issue22.php.)