Mikhail Chernishov

IFA Gallery, Berlin – August 23, 2002 – October 13, 2002

“No additions – A principle solution has to be reduced on the essential”, is how Mikhail Chernishov words his intentions for a series of Pictures, which he had executed in 1961 for his first ‘living room exhibition’.

Chernishov radicalised what he had seen and read about in foreign art magazines; he knew about Malewitsch’s Black Square, about Jackson Pollock and Ad Reinhard, and wanted to carry them a step further – not creating a picture without image, but showing that a picture could be anything.

He realised that images did not need to be created, that he was already surrounded by a multitude of significant images. For the Pictures he therefore framed pieces of wallpaper.

He forced viewers to look at something that usually is only seen as a backdrop; or that is not perceived at all – even though everybody would have recognised all of the patterns, as only a dozen or so different wallpapers were at the time available in the Soviet Union. Nevertheless, the six Pictures were of course also produced: Chernishov did not slice ready-mades out of a wall, but glued wallpaper samples onto a rectangular base and framed them with slats.

Mikhail Chernishov was not trained as an artist; he educated himself. In 1961, when he had his first ‘living room exhibition’, he was just sixteen years old, and it was already clear to him that the official art of the Soviet Union or anything that was taught at the state art schools was of no interest to him.

For three years, from autumn 1960 to 1963 he was a regular visitor to the Inostranka, the library for foreign literature in Moscow, reading there during the day and initially visiting courses at evening school, but soon relying solely on his own studies.

He lived the life of a non-conformist artist, relying on support from his family and from the odd job, almost without possibility to exhibit any of his work publicly. From 1966 onwards he spent some time in mental health institutions and almost stopped making art. In 1980, he was finally permitted to leave the Soviet Union and settled in New York, where he still lives.

The retrospective of his work, Angriff – Arbeiten 1961-2002, at the ifa-Galerie in Berlin covers the years from his first show in his own flat in Moscow to very recent works, and shows how for four decades the foci of his visual analyses remained unchanged.

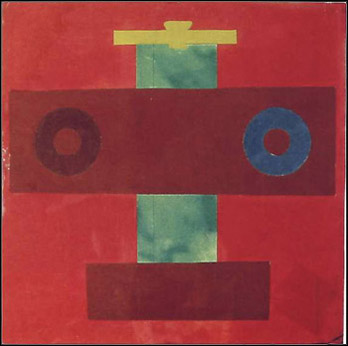

In his second exhibition in 1962, Chernishov presented cut-outs of fighter planes, tanks, transporters and maps from the military magazine ‘Sowjetskij Woin’ (‘Soviet Soldier’), calling them “water colours”, and several works on paper. For these very colourful collages and drawings, he took his subjects from the military images, yet depicted them in a very reduced, almost childlike manner, concentrating an airplane to a cross – made up of a rectangular body and wings -, and a van to two squares and two circles.

In more recent works, he still uses images of jet fighters, which are also still made up of very reduced geometric forms, though they seem to be constructed from roundish planes and cylinders, rather than of simple rectangular shapes.

In the reduction of complex three-dimensional machinery to simple geometrical signs, Chernishov plays with the possibilities of expression through symbols. One of his videos, The State of Suprematism, 1994, circles around different signs and symbols and their possibly contradictory meaning, by comparing the aesthetics of the Suprematists and of Nazi Germany.

The combination and repetition of symbols by Chernishov then again leads to patterns, which continue the original theme of the wallpapers.

Next door to the ifa-Galerie, in the commercial gallery of Marina Sandmann, who also curated the retrospective, is a second smaller exhibition with works on paper that places Chernishov alongside the work of Jurij Sawljewitsch Slotnikow.

Slotnikow, who is fifteen years older, belongs to the generation of artists, that first came to enjoy the liberties of the political and cultural relaxation in the nineteen fifties, thus making way for Chernishov, whose early work continues their primal analysis of visual signals and marks, yet is altogether far more radical.

Chernishov’s retrospective is accompanied by a small catalogue and by the German translation of his memoirs from 1961 to 1967, an enlightening view of his own motivation as an artist and of the non-conformist art scene in Moscow at that time.