Agency Gendered: Deconstructed Marriages and Migration Narratives in Contemporary Art

Throughout the past two years and in three consecutive exhibitions the Budapest Ludwig Museum has displayed parts of its collection, with an accent on recently acquired or rarely seen artworks. The show Kind of Change, which ran between March and May 2011, offered pieces purchased by or donated to the Ludwig between 2009-2011. The museum’s board selected works by Hungarian artists who have already entered the national canon of contemporary art, or who have made a name for themselves internationally, as well as works by a younger generation of East-Central European artists who are anticipated to become household names on the European scene.

After having lived and worked for almost two decades in Germany, Tamás Waliczky currently teaches at the School of Creative Media in Hong-Kong. In his short animation film The Garden (1991), which was shown as part of Kind of Change, the artist developed what he calls the “waterdrop-perspective.” This system replaces the traditional regime of perspective in order to prioritize not an adult viewer but a child protagonist. While the film can be described in fully technical terms, it is also a captivating visualization of what philosophers of epistemology call “situated knowledge,” a knowledge or cognizance that is specific to a particular situation (here, that of the child). One could rightfully argue that the recognition that knowledge is always situated, and therefore partial, is actually a cornerstone of all critical insight.(This argument reveals, at the same time, a leap away from a purely technological approach.)

The newly acquired artworks by Dóra Maurer (Reversible and Interchangeable Phases of Motion 1–¬6, 1972–75; Quasi Picture no. 1, 1977) and Gyula Pauer (Manifesto of the First Pseudo Exhibition 1–3, 1970) are well-known and revered pieces of the Hungarian neo-avantgarde. The often daring works by Romanian artists Ciprian Mure?an or the V?t?manu-Tudor duo are ever more familiar from group shows and biennials worldwide. Both Mure?an’s object (2006)—the inscription “Communism never happened” cut out of vinyls that once played propaganda music—as well as Mona V?t?manu and Florin Tudor’s film The Trial (2005), offer multilayered entries into thinking about an inescapably over-politicized past and its repercussions.

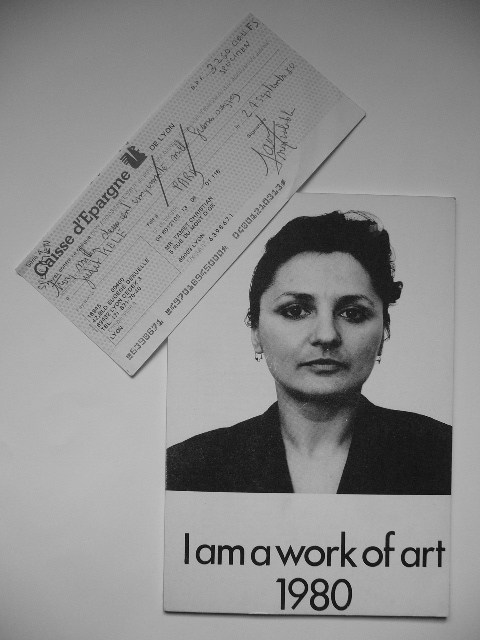

One work in the show that stands out is Judit Kele’s I Am a Work of Art (1979–85), which had disappeared from view for decades. But since Kele’s ensemble stirred great interest, it deserves a more detailed introduction and presentation, as well as further contextualization.

Kele graduated in 1976 in Textile Design from the Budapest Academy of Applied Arts. In 1979 she presented the photo performance Textile Without Textile in which she substituted herself (her own naked body) for the medium of the artwork by photographing herself as if her body were a thread running through a loom. In the following year she expressly placed herself in the role of an artwork at a durational performance at the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest. With a woman’s daintiness she composed herself into a perfect spectacle and spent the following three days sitting/living in the empty space normally reserved for a painting the museum had loaned for an exhibition elsewhere. Kele’s performance, together with the artist book I Am a Work of Art, inquired into the durability of the value of a beautiful painting or a beautiful human being.

Kele was an invited participant at the Paris Biennial where she prepared herself to be auctioned off as art. She thought that by selling herself as a work of art she might learn what she was worth. Armed with this knowledge, she would then be better able to take control of her life. The bidders invited to the auction were selected from among respondents to a classified ad that the artist had published in the French daily Libération. As the ad stated, through marriage the artist hoped to gain more freedom of movement than what her home country allowed her at the time.

The item put up for auction was a period of ownership of the artwork (the artist) for each Swiss Franc the bidder was willing to pay. This is how Judit Kele became the property of a Frenchman. The new owner wanted to keep his acquisition by his side, which at the time was only possible if he married his far-from-free wheeling Eastern European “artwork.” The groom was a prominent member of the Parisian dance world, and gay. This gave him an alibi for marrying a somewhat exotic Eastern European woman artist, an act that was advantageous for him as well (not to even mention the tax reduction for which he became eligible by becoming his wife’s supporter).

Initially, all parties involved, including Kele’s Hungarian husband, went along with the story with the brassy adventurousness characteristic of action art of the era. Except that this time the main protagonist was involved in an extraordinarily daring type of body art: she not only exposed her physical body but her entire existence to an unforeseeable process. And it soon turned out that the triviality of human relationships cannot be disregarded without consequences: he cohabitation faltered before the contracted life-time expired.(In other words, the adventure, initially considered as an art-only project by both “wife” and “husband(s)” soon penetrated into the sphere of “real life” and painfully re-arranged existing emotional and sexual relations.) Nevertheless, Kele never returned to live in Hungary.

In ways both intentional and unintentional Kele denaturalized the cornerstone of the hetero-normative social order, the institution of marriage built upon romantic love.(On Kele’s part, her willingness, indeed her conscious choice, to enter into a (mock-) marriage with a gay man was meant to make it likelier that that the purchased good was regarded as an artwork, and not as a woman. At the same time her choice betrayed a certain degree of comfort with non-normative sexualities. This might be revealing for those who envision “communism” as a site where heterosexuality goes unchallenged.) Her project is therefore immensely valuable for a reconsideration of the alleged presence or absence, during state-socialist times, of artistic perspectives that problematized gender regimes. The 2009 MUMOK-show Gender Check(Gender Check: Femininity and Masculinity in the Art of Eastern Europe, curated by Bojana Pejic. Exhibitions: MUMOK, Vienna, November 2009–February, 2010; Zachenta National Gallery of Art, Warsaw, March–June 2010; http://erstestiftung.org/gender-check/.) set out to provide a comprehensive picture of art that focused on gender roles, produced in the region from the 1960s till today. The project featured over 400 works. In order to also shed light upon more inconspicuous aspects of various national art histories, the show was preceded by extensive research within all the countries involved. Judit Kele’s performance somehow eluded this mapping process, but audiences had a chance to encounter its first reconstruction at another exhibition, Agents and Provocateurs another international research-based show that ran almost parallel to Gender Check.(Agents and Provocateurs, curated by Franciska Zólyom and myself. Exhibitions: Institute of Contemporary Art—Dunaújváros, Hungary, October–November 2009: Hartware Medienkunstverein, Dortmund, Germany, May–June 2010; www.agentsandprovocateurs.net) The exhibition surveyed certain forms of agency and provocation and the degree to which these stances can be viable forms of protest in changing political contexts.

Agents & Provocateurs juxtaposed artistic interventions from state-socialist Eastern Europe and more liberal-democratic political contexts in order to explore how genuinely critical attitudes need to adjust in order to capture a given system’s deficits. One sub-theme of Agents and Provocateurs was housed in a section entitled Agency Gendered. Under this heading the private sphere and its life strategies were viewed as potential sites of resistance to the social order. The section was designed in recognition of the fact that discussions of oppositional art in state-socialist East-Central Europe generally privilege open confrontations with state power over the totalitarian control over private life. Interestingly, when the oppressive features or unjust hierarchies of governance and control become themselves the subjects of critical reflection, more frequent references are made to strategies that see the private sphere as a terrain of resistance.

Rather than focusing on the representation of women and their imposed social roles, most pieces in the Agency Gendered section reflected on the intersection between gender roles and other aspects of politicized identity. Thus Serbian artist Milica Tomic’s action-documentation Belgrade remembers… problematized both the marginalization of the female protagonists of the anti-fascist past and the objectification of women in today’s mass media. Conceptually following this lead, VALIE EXPORT’s (A) Tap and Touch Cinema (1968) confronted the spectator-participant with the deeply engrained sexist attitudes that characterized Austrian society in the post-war decades and that were normalized in (visual) culture. Latvian artist, Andris Grinbergs’s 1972 film Self Portrait presented an alternative, communal lifestyle that surpasses the dictates of heterosexuality that continued to be prevalent in both Eastern and Western Europe at the time.(In the Central European imagination, the post-war and especially post-1968 West often features as a site of general “freedom” where both homo- and bisexual desires could safely be acted out. However, British and American researchers have chronicled official atrocities against homosexuals in their own countries of the “liberal” West (see e.g., Jonathan Katz: Gay American History: Lesbians and Gay Men in the USA, New York, 1976; or Lucy Robinson: “Three Revolutionary Years: The Impact of the Counter Culture on the Development of the Gay Liberation Movement in Britain”, in Cultural and Social History 2006:4).)

In Agents & Provocateurs, Judit Kele’s I Am a Work of Art entered in a dialogue with the activities of women artists who de-sacralize the traditional matrimonial bond (examples include Ewa Partum’s Women, Marriage is Against You, 1980 and Tanja Ostoji?’s Looking for a Husband with E.U. Passport, 2000–05), or who thematize the coercive and restrictive force of geopolitical factors on individual life (Ostoji?; Tímea Oravecz). Kele, Ostoji?, and Oravecz are from different generations, but their particular works on display in this show focused on social and professional mobility. All three artists aspire to move from the “other half” of Europe, from peripheralically Western” Hungary and ex-Yugoslavia to the Western European cultural centers (13).

Kele and Tanja Ostoji? appropriate the institution of marriage both as an artistic strategy and as a means of social mobility, but with different connotations. In 2000 Ostoji? published a rather particular photo of herself as part of a classified ad on the Macedonian Contemporary Art Center’s Gender & Capital project website. Its laconic text included a sentence inviting applications to write to the titillating email-address hottanja@hotmail.com. As Ostoji? writes, she

exchanged over 500 letters with numerous applicants from around the world. Following a correspondence of six months with a German man, Klemens G., I arranged our first meeting as a public performance in the field in front of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade in 2001. One month later we officially married in New Belgrade. With the international marriage certificate and other required documents, I applied for a visa. After two months I got one entrance family unification visa for Germany, limited to three months, so I moved to Düsseldorf, where I lived officially for three and a half years.

In spring 2005 my three-year permit expired, and instead of granting me a permanent residence permit, the authorities granted me only a two-year visa. After that, K. G. and I got divorced, and on the occasion of the opening of my Integration Project Office installation at Gallery 35 in Berlin, on July 1, 2005, I organized the “Divorce Party.”

On the one hand, there is Kele’s matter-of-fact text-only classified ad and the reserved and strikingly respectful tone of the handwritten responses. On the other, there are the snappy e-mail replies to Ostoji?’s picture ad, which deliberately appropriated sexual service ads or mail-order bride catalogues, except that the stark naked woman on offer in Ostoji?’s ad was not presented in an inviting physical posture. Her frontally photographed body is blatantly and fully exposed and is shaved off all body hair, while at the same time she securely owns the gaze, self-consciously staring at whoever may be watching her.

Many of the replies Kele received came from men who offered her their help out of what might be called “leftist comradeship:” they revealed the sender’s political affiliation as well as their awareness of how the project of communism went awry under state-socialism.These messages do not only outline the particular status of an Eastern European woman in Cold War Europe, they also suggest that marriages of convenience are nothing short of normal as the senders repeatedly assure Kele of their sympathy for her initiative. Ostoji?’s mail-order marriage, on the other hand, belongs more in a post-socialist or post-war setting, reminding us that “women’s bodies have been bought and sold to alleviate economic hardships throughout history; they have been used for punishment and war retribution, traded and trafficked across borders”.(Jehanne Marie Gavarini: Passports? The Subersive Performances of Tanja Ostojic. In Aspasia: The International Yearbook of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern European Women’s and Gender History, no.5 (2011; forthcoming).) The e-mail correspondences Ostoji? incorporates in her installation and in the Wedding Book (an album containing all the documentation related to the matrimony) do not so much respond to the inherently politicized situation of a woman seeking political shelter through marriage to a EU-citizen as they are over-determined by nudity and the sexual connotations of the advertizing image, titillating even in its dark perversity.

The formal presentation of the correspondences and the related material also differ between the two artists, as the two female protagonists in both projects assume different roles. In 1985 Kele stopped working as a visual artist and took to filmmaking, which partly explains why her scarcely recorded works and performances, including I Am a Work of Art, remained practically forgotten and unknown even to local art historians. When she reconstructed the piece in the framework of the exhibition Agents and Provocateurs, she practically gave the curators a free hand to arrange the retrieved material (the original letters; lwedding photos; an artist book; blown-up prints of the performances; as well as a documentary interview footage, and an art video)(The video is a new work. Invited to participate in Agents and Provocateurs, Kele reflected on the questions raised by the original performances after thirty years. The film addresses the social/cultural mechanisms for assigning cultural value, and how these are affected by the process of aging. It also holds up the possibility of liberating relationships leading from the hetero-normative matrix. (The film was not purchased for the Ludwig collection.)) for the installation. Ostoji? carefully designed her large-scale installation down to the hue of the wall paint and included professionally mounted C-prints of entry visas, event documentation, as well as emails with attached images—an aestheticized and comprehensively structured presentation that ran counter to the heterogeneous nature of the material. As both a woman and a beginning performance artist, Kele naively and boldly nose-dove into an increasingly self-propelling process that today she describes as an instance of self-victimization. Ostoji?, by contrast, confidently controlled the situation as she kept her project within the confines of an art project.

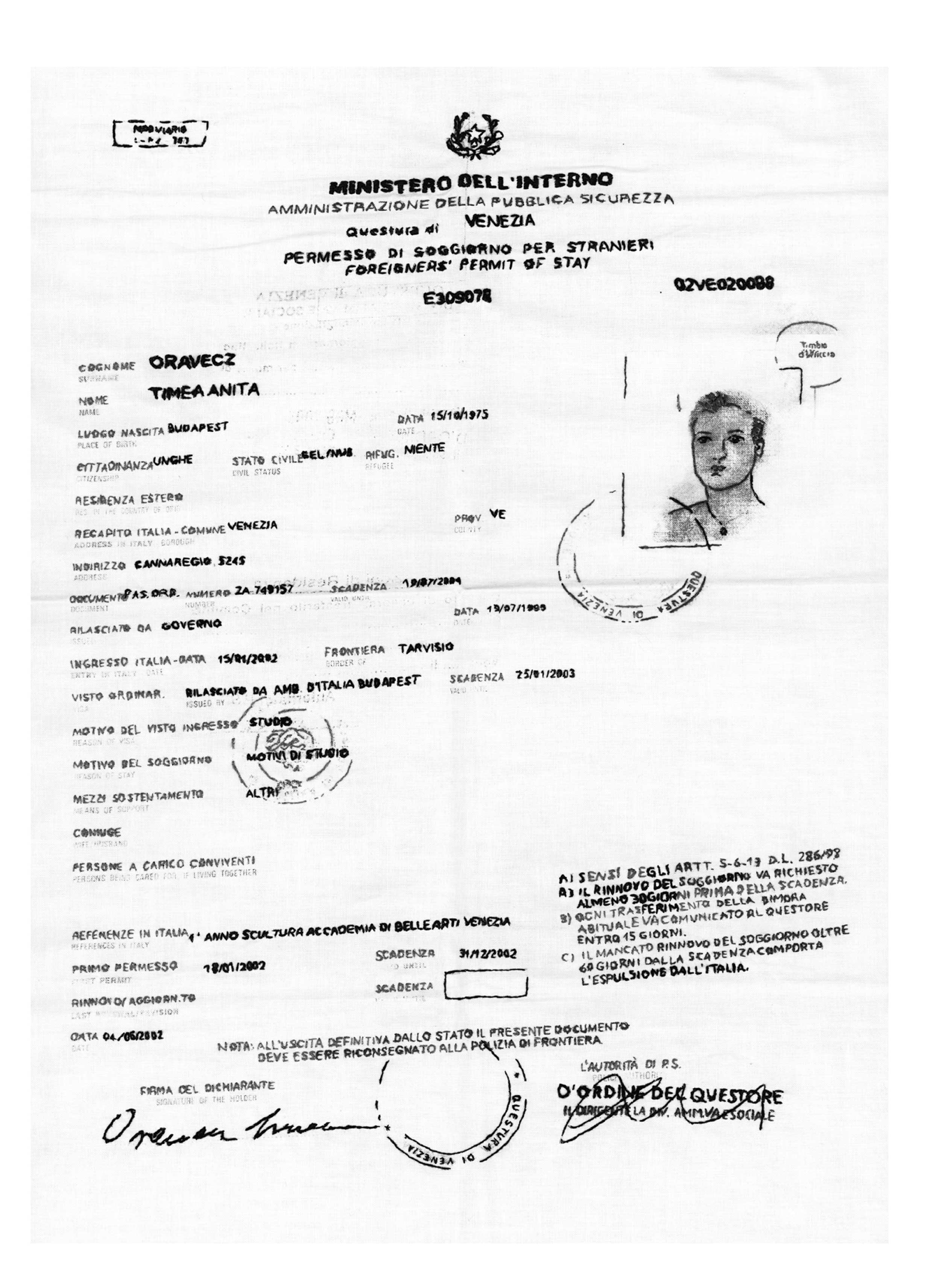

Hungarian artist Tímea Oravecz tells another contemporary narrative of social and professional mobility from the periphery to the center(s). In that narrative, the individual starting from the position of Europe’s disadvantaged “Other within” is once again driven to use illicit means in order to achieve her goal. Oravecz started her studies at the Akademie der bildenden Künste in Vienna in 1998, before Hungary joined the European Union. Later on, she attended art schools in other countries (Italy, Spain, Germany), enrolling either as a student or as what she describes as a “long-term tourist.” Meanwhile Oravecz’s native Hungary became part of the (allegedly) borderless and united Europe. Despite this, obtaining the documents needed for a legal stay in the EU remained an exacting and time-intensive process that occasionally drove the artist to forge residence permits, social security numbers, or bank accounts. The series Time Lost (2007) presents acquired administrative documents from a period of nine years (residence permits, visas, passports stamps) in embroidered patterns. Oravecz tries to embroider every tiny letter, code, stamp and signature on these forms, even if the task proves time-consuming, senseless, or at turns simply undoable—and even if she occasionally hurts herself with the needle. The same subject is picked up in the video-installation Cosmopolitan (2009), where in three films the artist relates, in different languages (Hungarian, Italian and German), the absurd difficulties of changing her residence from one country to another. She dispassionately lists the kind of forgeries and lies that self-contradictory regulations within the EU have compelled her to commit. The sound effects of these simultaneously running monotonous narratives are cacophony and befuddlement over the discrepancy between the proclaimed liberty of EU-citizens and the artist’s own frustrating experience. essay

It is intriguing to note how the time of conception and the means of execution impact the three works discussed here. In the “marriage projects” by Kele and Ostoji?, the transformation of the channels of communication has a dramatic effect while the two decades that have passed between them also impose important changes in both artistic and female consciousness. Gender as an organizing force, or femininity as a potential resource, are absent from Oravecz’s approach; in fact the younger artist no longer even falls back on feminine charm or attractiveness as part of her “strategies of success.”(Strategies of Success is the title of a publication covering The Curators Series, a number of performance pieces in which Ostojc thematizes the often sexualized relation between curators and female artists.) Ostoji? is a well-known representative of East-Central European contemporary art today, while Oravecz is a “young and emerging” artist. Having studied with Olafur Eliasson in Berlin and winning a number of awards internationally, so chances are that we will be hearing about her repeatedly. And it is thanks to the freshly enriched collection of the Ludwig Museum Budapest that Judit Kele’s work is saved for future generations of viewers and researchers.