Mark Verlan (1963-2020): An Absolute Totality

Mark Verlan, Maastricht, 2000. Photograph courtesy of Octavian Esanu

Moldovan artist Mark Verlan passed away in Chişinău on the eve of this new year. Known by many names – Marioka Son of Rain (Marioca fiul ploii in Romanian and Marioca sin dozhdea in Russian), Marioca Son-and-Rain, or simply Mark, Marc, Maric, or Marik – he died at the age of 57 of a heart attack. Some names were given to him, others he chose (like his nom d’artiste “Son of Rain”), and the rest are the result of Moldova’s bilingualism, or the local preference for diminutives used to convey endearment or playful respect. His many names and spellings contributed to an aura of mystique that also results from a dearth of available personal and biographical information, not to mention a lack of art historical research. This text, then, cannot be an obituary, promising a solemn recitation of facts about the deceased. It is a eulogy, a paying of tribute, an imagined participation in a missed funeral procession, and ultimately, an essayistic reflection woven from a few details from Mark’s life and some ruminations on the concept of “totality.” Having known Mark for years, I am certain that this is what he would have preferred.

Like the lives of many Eastern Europeans of his generation, Marik’s life – spanning a little more than half a century (1963-2020) – was divided into two almost even halves by the year 1989. The first was formed by “real” or late socialism, and the second by “democracy” or neoliberalism. Across this divided span, Marc came to occupy a unique niche in the artistic scene in Moldova. Although well-known and beloved by his peers, by his patrons, and by “the people,” and though he was one of the main sources of inspiration for post-1989 Moldovan contemporary art, he was neglected by the cultural elites, by chairmen and chairwomen, by presidents and by ministers of culture of both socialist Moldavia and capitalist Moldova. To the state and its cultural institutions he remained unknown. It is to those who did not have a chance to know him that this eulogy is addressed.

His funeral was quick, given the state of the coronavirus pandemic. The burial consisted of a cortège of vehicles following Marc’s body to the place of eternal rest: the Armenian Cemetery in central Chişinău. After he dutifully served his entire life as an unofficial artist, his friends and followers had to struggle in order to secure a burial lot in the most important cemetery in the country. The friends believed that Mark deserved a place in this graveyard, but when approached for permission to obtain a plot, or to use one of the state’s cultural installations (like the National Palace) to arrange for a small farewell ceremony, the cultural liaison to the newly elected national-liberal pro-European president replied that Mark had not earned any state awards or prizes (premia) to deserve any special treatment. His friends responded by pulling strings with the office of the mayor, and it worked, as it always does in Moldova and in other democratic countries.

Mark Verlan with his banner, 1995. Photograph. Mark Verlan’s Documentation Folders. Image courtesy KSA:K – Centrul pentru artă contemporană, Chișinău

Then on January 4, 2021, following lubrications and arrangements made by the center for contemporary art KSA:K among others, a handful of mourners and grievers finally joined in forming one last motorized procession heading through the streets towards the most important graveyard. The cavalcade followed Mark’s flag (installed on one of the front vehicles)—a green banner depicting a black cat seated in a sort of a deep yin-and-yang bowl, or on a zafu cushion, as if in a position of meditation or zazen. As the followers followed the coffin they knew that it was not only an inanimate body that they drove, walked, or stood by, but also a vision. And, while they knew that the body would soon be put to rest, the artistic vision called “Mark Verlan,” would remain in order to make sure that the ceremony unfolded accordingly under the green banner of the enlightened cat.

Mark’s flag has led many processions and journeys in the past, including funerals. In 1995, for example, the same flag escorted a mixed crowd of citizens to the place of burial of a Barbie doll with a missing leg, which Mark had found in the streets of the city and whom he decided to give a public funeral. Back then it was Mark who shouldered the green banner, marching through the streets of Chișinău followed by a few devotees carrying a tiny red coffin with the desecrated body of the iconic American product. The flag carrier and the bearers were escorted by a small public for new art, a loud police brass band playing military and funeral marches, and by a growing crowd of disconcerted civilians. As the procession processed, more and more bystanders and passerby joined the bizarre ceremony. Those of us involved in the organization of the Exodus (including the local sage Albert Șvets) remember the event too well, as it led to the enlightenment and salvation of a few who since then call themselves “contemporary artists,” and to the profound confusion of many ex-socialist citizens and policemen, who have remained for three decades now a baffled audience of new art and free-market postsocialism. The culmination of that liturgy came at the end, when Mark was putting the tiny coffin containing the one-legged doll into the ground. As the police orchestra was delivering its most mournful Soviet funeral hymn, a heavy storm suddenly broke the sky, washing away the entire ceremony (including the tables laid with food and drinks under the open air by the local Soros foundation’s art and culture program for all of those who came to commemorate the “departed,” as per the local Christian Orthodox tradition). It was, after all, the Son of Rain.

Mark Verlan with his banner (right) and the public paying farewell to the legless Barbie doll. Exodus, Chişinău, 1995. Photograph. Mark Verlan’s Documentation Folders. Image courtesy KSA:K – Centrul pentru artă contemporană, Chișinău

And now twenty-five years later, another funeral procession has taken place under his banner. This time everything was much more simple—there were no brass band, no confused citizens, no rain; only a few friends, followers, and Covid-19. When thinking of a word that might be best suited to describe Mark to those who did not have a chance to know him, the word “totality” first came to mind. Although the idea is of older origin, in the early modern age totality was much favored by the Romantics, the German Idealists, and later by the Marxist dialecticians. With the rise of industrial capitalism, totality conveyed a longing for the disappearing communal way of life, and a dismay over fragmentation and the loss of collective coherence. Art, which was emerging as an autonomous institution, was considered, if not a substitute, then a consolation for the loss of the “whole,” and for the disenchantment of life. Along with religion and philosophy, art was called an “absolute totality,” as it was believed that these realms of human practice were fully self-sufficient, like the former feudal agrarian communities that did not depend on external resources. As an absolute totality, art did not rely on outside norms but rested on self-derived totalizing principles, i.e., norms of composition, harmony, color, rhythm, perspective. It occurred to me, then, that this absolute, total self-sufficiency and self-reliance of art, as a system organized in-and-for-itself, somehow, very much, applies to the art and the life of Mark Verlan. There was no gap between his art and his life (the very gap that the aesthetic radicals of the twentieth century avant-gardes swore to eliminate). In Marik’s case, art and life perfectly overlapped.

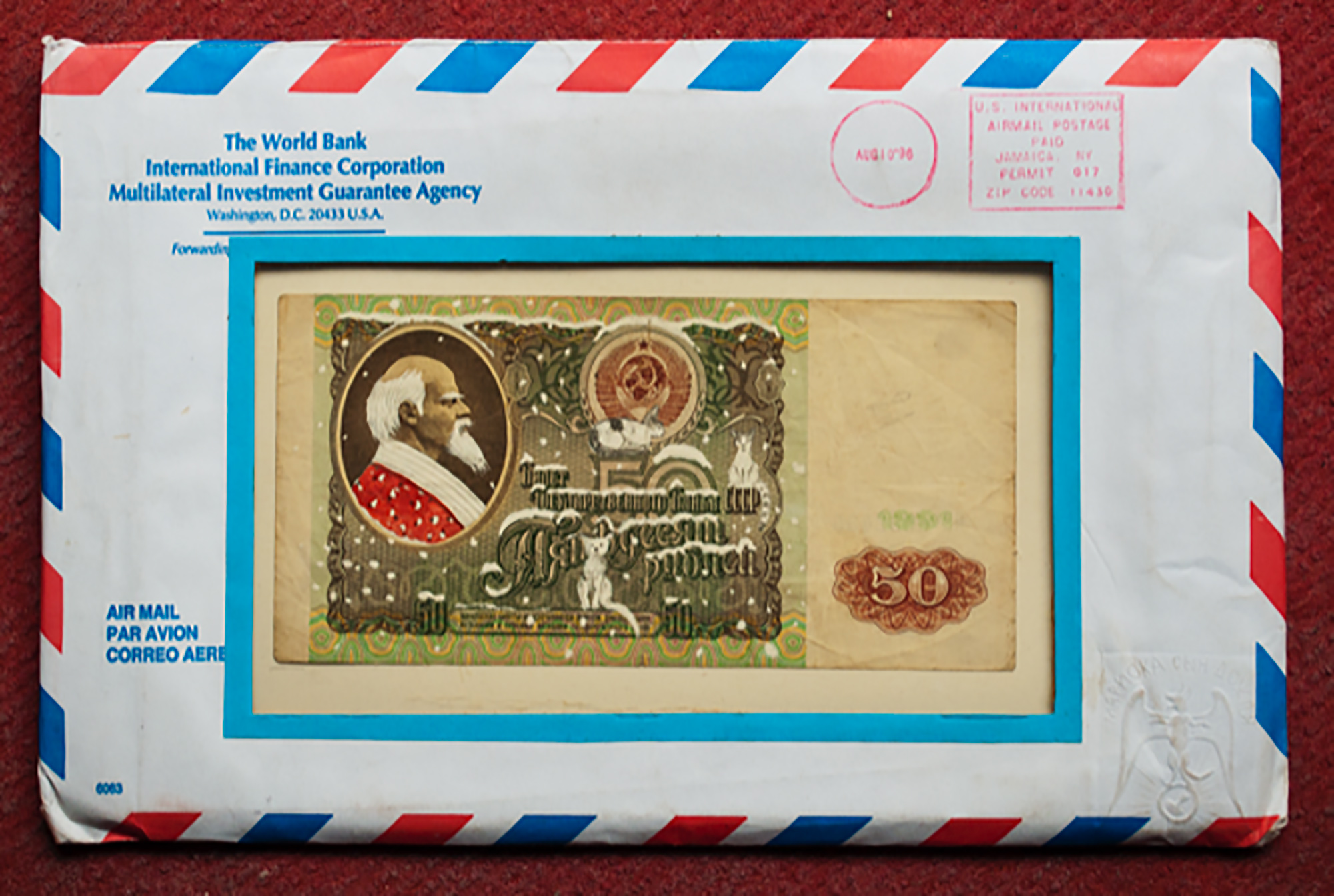

Mark Verlan’s money. Painted over devalued Soviet banknote framed in a World Bank envelope, mixed media, c. 1993. Mark Verlan’s Documentation Folders. Image courtesy KSA:K – Centrul pentru artă contemporană, Chișinău

So, when the deceased body of Mark was driven, and then carried, to the central graveyard of a state which did not want to know about him, there was no difference between Maric, the “human body,” and the “body of his work.” Together they formed one total “body of art.” This totality took shape over many years, and by the time of Marc’s death it already formed a complex system with multiple interacting elements. Earlier on I mentioned that Mark was never given an award from the state (this applies both to the pro-Russian Bolsheviks and the pro-European nationalist liberals: two political extremes that have competed for the governance of the country surrounding its central cemetery for the last few decades). But, Mark did not really need an award offered by a nation-state (which, as it will be shown below, is considered a “relative totality”). A state prize may have even perverted or disturbed the absolute totality that was the Son of Rain. In his universe there was everything he ever needed, including awards, medals, and decorations, which Mark made and gave himself whenever he felt he deserved one. “Mark Verlan” was a fully constituted entity, a-state-within-a-state: with his own flag (the cat in the state of nirvana); his coat of arms showing again, a cat in meditation, or as per another motif of his heraldry, a winged cat carrying a tiny kitten sitting in zazen; his own dress code with different types of garments, headdress, helmets, and hats (some hats were made out of concrete, ceramics, plaster, wood, or metal); various purses, suitcases, and other accessories (used for their intended purpose but also serving as frames for his paintings and drawings); a currency (Mark put into circulation his own banknotes and coins); his own anthem, maps, certificates; a globe (yes, the globe of the Kingdom of Rain, which is co-extensive with the “globe” of the Republic of Moldova); his own throne, furniture, shoes, eating and cooking utensils; glasses and spectacles made of various materials; letters, stamps, seals, sealed and empty envelopes; a great number of paintings, ceramics, drawings, graphics, sculptures, posters, and endless other media and documents, decrees, orders, patents, poems, novellas, some written in his own language using a grammar and an alphabet that he had invented and perfected. His totality was absolute, complete and self-sufficient, and Mark lived in it like Robinson Crusoe, on a fully inhabited island once called the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic (RSSM) and now simply the Republic of Moldova. As he never owned real estate, no apartment or house or even a studio, Mark’s universe was packable and always ready to move around every few years or so to a new base (usually provided free of rent by his multiple affluent admirers). The houses that he was given to inhabit were then transformed into “total households” where most of the domestic objects, from the satellite antenna to the TV and other appliances, were again hand-made or re-purposed by Mark. His life was in the making of the splendors of his realm, and in the regular and generally very cordial interactions with the island’s inhabitants. As an absolute totality, he did not rely on the outside world: on its rules and norms, on its time-space continuum, or on the political and economic categories regulating the life of everyone else on the island. He was his own rule, like the thieves in whose company he was often seen; everything he ever needed he awarded to himself or made with his own hands—an autonomous system, a self-sufficient organism that reproduced itself through the division and unity of its elements, in a state of continuous repetition.

Mark Verlan’s household objects (headdress series). Clockwise: Helmets for Past and Future Wars, mixed media, c. 1990s; Concrete Ushanka-Hat, concrete, c. 1986; Clay Ushanka-Hat, clay, ceramics, c. 2000; Bicorne Hat with Marc’s Insignia, clay, ceramics, c. 2000s. Mark Verlan’s Documentation Folders. Image courtesy KSA:K – Centrul pentru artă contemporană, Chișinău

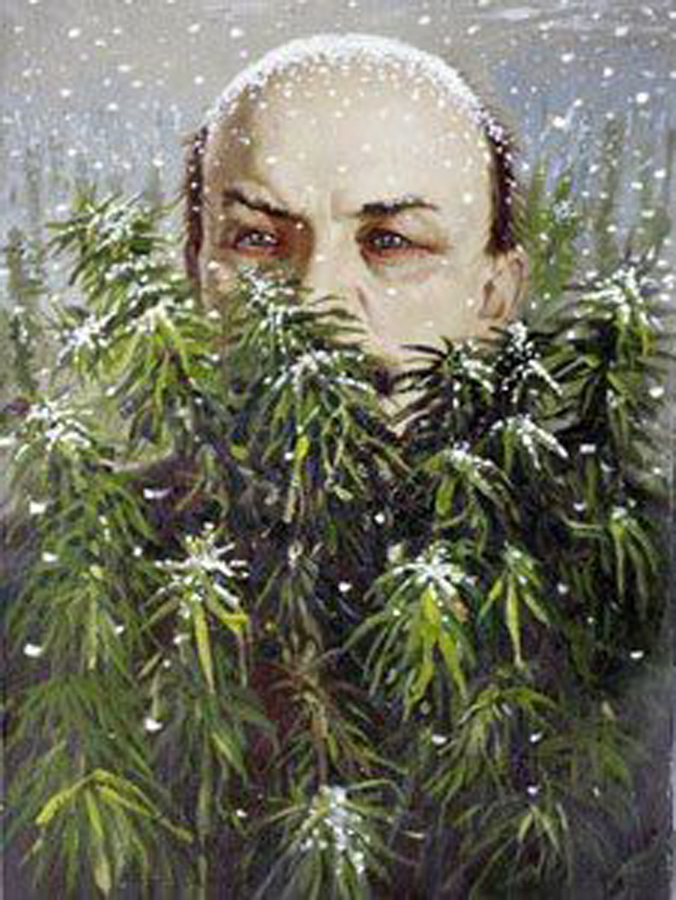

As the cortège drove towards the cemetery, people described this unique organism that had so little synergy with what we often call actuality, empirical or social reality, nature, the Republic of Moldova, the Kingdom of God on earth, the desert of the Real. Changes in this “reality” had little impact on Marc’s globe. In the first, pre-1989 half of his life’s story, he was not susceptible to communist political or aesthetic conventions, although he never openly denounced them. Like most Moldovan artists he attended Kishinev’s Ilya Repin school of art (renamed as Alexandru Plămădeală, after 1989), where he gained notoriety for his unmistakable eccentricity. But he was not a dissident. Mark did not live in the conviction that the hardness of life in socialist totality could be overcome only if we replaced one totalizing principle (the utopian dream of equality) with another (the norm of capitalist exchange). He did not comment on his political views, remaining firmly a- or anti-political, but without being socially regressive, like today’s neoliberal democrats who disdain politics (genuine change) for fear of totalitarianism, or because they think that the market will sort all things out. Mark also did not believe, or maybe did not care to wonder if, a better place, lay out there over the Wall, as did the pro-Western dissidents. He did not compare, dismiss nor critique the political or aesthetic universals of late socialism but was simply blind and immune to them. Whether his was an inborn immunity, or whether he acquired it through phases of vaccination, we may never know, as he was not the object of systematic study by the island’s art historians. The Son of Rain remained faithful to, and invested only in his own joys and weaknesses. Under late socialism, when his peers were critiquing or exploiting the socialist totality for their own benefit (i.e., making portraits of Lenin in exchange for rubles), Mark was making portraits of cats and dogs, as if in order to rebuff the fashionable French theorists who at the time insisted that animals did not have faces. But this does not mean that he completely disregarded the main symbols and totalizers of the existing social order. He also took great pride, for example, in painting the leader of the world proletariat, only that his Lenin was different: small, insignificant, frightened, staring at us from behind a bush of cannabis, with red eyes, snowed upon and lost in internal contradictions—a Lenin of the Western Marxists and other hippies, rather than the firm statue-like image fanaticized by local apparatchiks.

Mark Verlan, Lenin in a Bush of Cannabis, oil on canvas, Date unknown. Mark Verlan’s Documentation Folders. Image courtesy KSA:K – Centrul pentru artă contemporană, Chișinău

And then, after 1989, Mark did not rush to embrace “new values” but kept expanding the household of his oikonomia. He did not turn to new topics or themes (as did many who quickly replaced Lenin with Jesus, or with national heroes); neither did he follow the example of a new breed of artists who proudly called themselves “kontemporary” for giving up on – or for never learning in fact – painting, sculpting, or drawing, and who chose instead to stage narcissistic stories of their identity and difference in front of cameras bought by grants offered by American hedge fund managers or rich West European burghers. Certainly Mark also benefited from grants, as we all did (and still do). He was one of the main sources of inspiration for launching a Soros Center for Contemporary Art in Chisinau (CSAC), in 1995; and he was also one of the first artists to be part of this center’s documentation program. A researcher could still find in the archives of this center a few folders containing documents of Mark’s total universe. But even though he was well-documented, and well-promoted, being in fact “patient zero” in most of the events organized by CSAC (later called KSA:K – the only, and unfunded, contemporary art center in Moldova) he never really or full-heartedly joined the so-called “contemporary system of art,” as he never embraced the “modern” one before 1989. He stubbornly carried on as a planet of his own. Maric never learned English, remaining tenaciously monolingual, or communicating in his own invented language, grammar, and alphabet; he did not plant nor cultivate a CV (Mark never had a proper vitae); he did not make an artist portfolio, or any personal website in order to pronounce himself an asset ready for injection by capital (his scarce presence online and in the social media was due to his fans). He was un-neoliberal and un-contemporary in that he was not a self-promoter—but again, like under socialism this was not by purpose but by lack of purpose. He only kept tilling his garden, alone or with Friday, his late wife Valentina Tuzova (of whom he once said: “I used to draw her my entire life and then I met her”), and for the remainder he kept busy entertaining the island’s cannibals or being a nuisance for its visiting headhunters and contemporary art curators and such: an absolutely unmanageable, unreliable, and incuratable case. As in late socialism, Marik managed to survive the market regime of life by partially or completely detaching himself from the rest of the world, and remaining invested only in his household, which kept expanding under the green banner of the enlightened kitten. In the temporality of his universe, there were no clocks, no calendars or other instruments of time; there were no markers or historical ruptures—no strict separation into History and “post-history,” into state’s communism and market’s democracy. He lived in a condition of continuous self-creation by painting, sculpting, making, composing or writing about the same things over and over again: flying cats, dogs always reading one and the same book, and Lenin. After 1989, however, his Lenins were also different from the rest, being caught too often in the suspicious company of Buratino (the Russian version of Pinocchio)—like the forces of the New Left who tagged along with the former class enemy after the fall of that Wall.

Mark Verlan’s variations on the motif of Lenin and Buratino (Pinocchio). CLOCKWISE: Lenin and Buratino on Red Square, oil on canvas, undated; Lenin and Buratino, drawing, c. 1989; Lenin and Buratino in a Field of Cannabis, oil on canvas, undated. Mark Verlan’s Documentation Folders. Image courtesy KSA:K – Centrul pentru artă contemporană, Chișinău

Since he was denied a cultured venue in an establishment of the nation state, Marik’s followers improvised a site of commemoration right in God’s acre, so to speak, in a corner of the main cemetery of the republic. Again, they stood under the green banner of feline enlightenment, drinking to his soul, or retelling stories about his world. Maric’s full commitment and attention to his universe, or the Kingdom of Rain, often put him at odds with both past and current political and aesthetic regimes. Culture’s bureaucrats, and then contemporary art curators and even some artists, often dismissed him as a sort of “outsider artist,” and this was because they could not recognize in the sovereignty of his universe the familiar political or aesthetic categories of their “real world.” Under socialism they could not find in the body of Mark’s art any serious representations, expressions, or allusions to the central categories of socialist modernism (class struggle, socialist content, national form); and after 1989 there were no traces either of the new ideologemes of market democracy and contemporaneity (identity, freedom, the open society, sexuality, Duchamp, and many other ready-mades that motivated artists’ grant proposals and the mission statements of local NGOs). The pictorial, sculptural, and graphic universe of the Son of Rain had no need of any such external signifiers, as if Mark lived in the same space but in different time zone or even epoch. He was indeed an “outsider” in that he fused cultural standards from different epochs: premodern paganism, devotion to artisanal skill and mastery over material, combined with modern qualities, such as originality, expression, fantasy, irony, construction. His artistic vision lay in parallel to but never really touching the time-space continuum of “modern/contemporary art” and of “communism-socialism-1989-national-liberal-market-democracy.” And even though his world also referenced many recognizable cultural symbols from these epochs, their presentation had often been eccentric and distorted, like a signal returning from a distant planet. His was a faraway universe that did not advertise itself, did not denounce, critique, or show resentment towards the progress of the “main” world, but simply endured, in its simple presence, as if silently saying: “Hey you ‘real world,’ hey you ‘art world’ up there! You are not the only one possible.”

Thus far I have been suggesting that Mark’s universe, his vision, his relation to the world can be described via the notion of totality. But not all totalities are equal. Distinctions have been made between absolute and relative totalities. The latter depend for their coherence on external factors. One example of relative totality is the nation-state and its various customs, apparatuses, and institutions—the very ones that give or deny recognition to artists. The state and its institutions are “relative,” “finite,” “partial,” or “sub-totalities” because their reality is contingent on the ideology of the group or class whose interests they serve. Other examples of relative totalities include forms of knowledge, like art history, art criticism, or aesthetics, that are relative with regard to the absolute totality that is art, because the latter constitutes their object of study. For the precursors of critical theory, only art, philosophy, and religion were by contrast “absolute,” given their full self-sufficiency to address and deal with the infinite depth of the Spirit.

Mark Verlan. From the Household Objects series. CLOCKWISE: Wine Pitcher, clay, ceramics, c. 2000s; Wine Cup, clay, ceramics, c. 2000s. Mark Verlan’s Documentation Folders. Image courtesy KSA:K – Centrul pentru artă contemporană, Chișinău

But how about the relation between absolute and relative totalities, between artists and the state, with its customs and its cultural, artistic, or funeral institutions? The question is particularly pertinent for a category of artists whose universes burgeon independently of the concerns of state institutions or relative totalities. Mark is a good example here, as he managed to remain an “unofficial artist” under diametrically opposed political regimes. Categories (like those of a relative totality like art history) slipped off, like rain off a duck’s back. This explains his frequent dismissal as an “outsider,” “insane,” “psychotic,” “autre,” “naïve,” and so on. But this resistance may have wider consequences for our disenchanted world. We have lost the capacity to distinguish or to accept a wide range of affects and aesthetic states generated out there “in the wild,” outside the walls, norms and expectations of the institutions of art, culture industry, and academia, outside of all these relative totalities historically constructed around hegemonic interests. We may have lost the faculty to see or discover universes built by parrhesiastes like Mark Verlan, who simply cannot prevent themselves from being what they are, or who are purposefully repressed or treated with clinical detachment as some manifestation of unreason, or as a vestige of a distant, “enchanted” world.

The distinction between absolute and relative totalities is also applicable to artists. Mark’s totality is “absolute” because he could organize a manifold of sensations, a unity of opposites, fields of symbolically resolved contradictions, into one Universe that existed in-and-for-itself, based not on categories borrowed from outside but on self-derived totalizing principles. His art did not rest on “relative” political or aesthetic concepts (i.e., naturalism, or socialist realism before 1989, and identity politics mixed with Duchampism after 1989) but was made to suit his world, as archaic as it may seem today, a world resting on his own stack of turtles, or its unique signifiers: “Cat in Zazen,” “Flying Dogs,” or “Lenin and Buratino” (some of the most common motifs in his art). And like with the “main” Universe itself we can look at Mark’s world with great interest without any need to resort to relative totalities: like reading art historical interpretations; glancing over his CV that he did not have; gleaning clues from labels under his works; or counting the awards given by national-states or transnational corporations.

As the bearers lowered the casket, some cried while others observed in silence Marik’s departure from this world. The problem of absolute totalities is that they are not always on good terms with the relative (and for Mark, with his family relatives) or with other partial and sub-totalities. State socialism was one such relative totality, which we may also call “dogmatic,” or “repressive.” In its Soviet orthodox, Marxist-Leninist version, there could only be one Totality, which from the outset declared itself “absolute” (too hastily perhaps, and with later regrets). So when a new endogenous entity, like “Mark Verlan,” shows up carrying a green banner and making totalizing claims, by promising coherence, aesthetic consensus, and eternal harmony (for this is what totalities do) he was instantly perceived as a threat undermining the legitimacy of the “onliest” totality possible. And for Western progressives, totalities have always been more of an aspiration, which may or may be accomplished—a beautiful Red Utopia, in other words, taught in the department of literature at the American private universities. For those embracing and practicing “Red thought,” totalities have been more of a longing, a hopeful alternative to fragmentation and alienation by capital. As far as the pragmatic and commonsensical market regime of justice is concerned, liberal democracies have had a profound dislike for totalities. With the triumph of capitalism in Eastern Europe, totalities have often been denounced for their alleged connection to totalitarianism. Contemporary capitalism’s tendency to isolate, individualize, deregulate and fragment everything by celebrating identities and differences, or by dismissing any need for wholeness or collectivity comes out of a fear of tyranny. Whether this has to do with genuine concern for freedom, or with capital’s tendency to divide and conquer, or both, I will let the reader decide. The ideological fathers of our current regime of market democracy, or demarchy, despised totalities, associating them with concentration camps or with “closed societies,” or referred to them in derogatory terms such as “holism,” “tribalism,” “aestheticism,” or the “poverty of historicism.” From Karl Popper to Friedrich Hayek and other Central European Cold War “liberals of fear” inspired by Austrian marginalist economic theories, the world of the liberal “open society” has been fancied as an assemblage of free and disconnected facts that come together as needed, or is mediated by the sub-totalities of various institutions acting within a “free market.” We see the effects of such fantasies in our everyday life, where the hero of the contemporary age is not the artist but the manager, the curator, the problem-solving engineer, the influencer and the scientist. Therefore, there was no place for Mark in either of two worlds that ran in parallel to his universe. Under socialism he was looked upon with suspicion for painting portraits of cats instead of Party leaders, and under capitalist democracy there was nothing in his world affirming the joy of private freedom, the delight of attending to his identity, or any unique conceptual or (post)conceptual speculations, cerebral “discoveries,” expected to be enjoyed solely under the hair of one’s head.

Mark Verlan’s Vision. LEFT TO RIGHT: Series of Glasses with Helmet, mixed media, c. 1995; Workshop on how to use Mark Verlan’s glasses organized during Kilometrul 6 Exhibition, photograph, 1996. Courtesy of Octavian Esanu and Mark Verlan’s Documentation Folders. Image courtesy KSA:K – Centrul pentru artă contemporană, Chișinău

From the fringes of the grave the followers tried to take away a last image of the Son of Rain. What was that image? When an absolute totality in the realm of art is invoked, one thinks of it in terms of a system of qualities that bears the mark of its own coherence or Oneness. What this mark called “Verlan” left to his audiences was not only the objects that he made – which some today have finally “discovered,” rushing to sell and capitalize on them, or emboss their image files with the copyright seal – but a vision, and a way of seeing. Like his series of glasses pictured above, he left us with an apparatus we can use to look at this world from a radically different perspective, thus letting us forget for a moment the most common political and aesthetic categories and lenses lent to us by the Party or the Market. No one succeeded in turning Mark into a mascot for an external cause, and this is because he was an external cause in himself. As one popular local story about him has it, when the late Harald Szeemann traveled through the region to select artists for his Blood and Honey Balkan exhibition, and when he came across Mark Verlan, he instantly made known his commitment to put on a solo exhibition somewhere in one of the cultured institutions of Western Europe. But Szeemann then passed away, and was carried feet-first under his own banner shortly after their encounter. It is as if some secret stratagem of the Almighty has prevented or delayed an absolute totality from being turned into a relative one, or made into a false category that serves the profane interests of this world. And maybe this is the way it should be. Rest in peace, Marik.

Mark Verlan. Title and date unknown. Mark Verlan’s Documentation Folders. Image courtesy KSA:K – Centrul pentru artă contemporană, Chișinău