Magical Mystery Tour

Davaj! Russian Art Now. Aus dem Laboratorium der freien Künste in Russland (From the Laboratory of Free Arts in Russia) 10.1.2002 – 27.2.2002. Open Tue – Sun 1-8 p.m., closed on Mondays Postfuhramt, Oranienburger Strasse 35-36, D-10117 Berlin, Germany www.davaj.de

When I entered the “Davaj! Russian Art Now” showroom, my first impression was that I had somehow fallen into Ilya Kabakov’s 1993 installation “Noma”, which presented his fellow Moscow Conceptualists as inmates of a lunatic asylum.

The same white, shabby walls, the same central room, from which corridors led into various directions, the same cells in which the artists presented their work – in fact, the first room to the left is shut off with iron bars.

This first impression, however, was soon superceded by a second: Davaj! is a far cry from conceptualist sternness. In fact, if Davaj! is anything to go by, currently video installations are all the craze in Russia’s alternative art.

Already the central room is full of monitors, and in most the rooms, there is at least one video screen showing subjects as varied as a naked man with a felt boot on his head (Maksim Verevkin doing a Shamanist ritual), dancing newlyweds (Lyudmila Gorlova, “Happy End”), and copulating computer-animated bunnies (“Kino Novosibirsk” by the Siberian group Blue Noses).

Some just put up a monitor showing films of their performances (Maksim Ilyukhin, Anatoly Osmolovsky and friends, Elena Kovylina). Others (Aleksandr Shaburov, Galina Mysnikova and Sergey Provorov) integrate video screens into larger installations.

The group “Escape” (Bogdan Mamonov, Anton Litvin, Elizaveta Morozova, Valery Aizenberg) present themselves as a travel agency where you can book holidays in Moscow, New York, Tsarskoe Selo, and Matyushino, in the footsteps of famous artists.

Places to visit are the Dakota Building where John Lennon was shot in New York, the sunrise of Russian poetry accompanied by D.A. Prigov singing Pushkin mantras in Tsarskoe Selo, or the artist’s dacha in Matyushino.

The beauty of these places is shown (or rather, hidden) in videos that feature random tours through the respective places – a New York taxi’s window obscured by rain, a walk through a park, a drunk on a Moscow street.

Where there are no videos, there usually is sound and color. In the group ‘Radeks performance “Accord”, a single chord is held on a portable keyboard by changing people. At the time of writing, the chord is traveling from Berlin to Vienna, the keys being pressed by anyone who cares.

Tatyana Hegstler’s “Buried Treasures” consist of a series of photographs covered with a heat-sensitive surface.

At room temperature, this surface is dark and opaque, becoming transparent only when it is heated with a hairdryer or the warmth of the visitors’ fingers. What is revealed, though, are people turning away or hiding their faces – even the lady who otherwise hides very little.

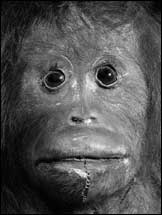

Oleg Kulik’s, as always, semi-frightening installation “Dead Monkeys” consists of photographic close-ups of 12 monkeys’ faces staring at you like ghosts, until you realize that they are all stuffed exhibits of a Natural History museum. “Only the art of a taxidermist could talk of the basic things. ‘Your soul will die before your body: Fear nothing!’ Though the human prefers to want Nothing, rather than nothing to want and nothing to fear”, the artist comments, putting the metaphysical shudder back in.

Aleksandr Shaburov has one room decorated as a museum to the Russian superhero Ivan Frog and his heroic deeds. Shaburov propagates a radical aestheticism in which every move by the artist becomes a work of art, and the whole world his material.

The futility of this position becomes evident in the absurd tale of the superhero whose life is told in a collection of household appliances, toys, comic books, drawings and other trivia which is perhaps the most reminiscent of Kabakov – although here again color and play abounds.

But if Davaj! looks like a colorful variety of Kabakov’s asylum, then how do the “inmates”, these diverse artists from locations between Kaliningrad and Vladivostok, position themselves? It is the context one must turn to.

All – or most – featured artists are in a situation where their artistic rebellion is not even noticed. As Anna Matveeva’s insightful catalogue article notes, there is nothing in particular against which these artists could turn, and no artistic “mission” (zakaz) for them to take on.

In this void, every artistic action takes on the nature of an acte gratuit which only serves to assert one’s own existence. But of course, this existentialist position has already been invalidated, too.

Therefore, the artist is thrown back onto himself as his own sole reference. Oleg Chvostov’s series of self-portraits, all executed in watercolor, all strikingly (though not completely) similar, and all a bit like a schoolboy’s exercises, give an effect similar to an insect’s compound eyes.

This, it turns out, is symbolic of the position the artist finds himself in – small, insignificant, noticed by nobody, looking exclusively at himself, trying to find various faces, but ending up with constant obsessive repetitions.

Here, the gesture of passing this off as art becomes a survival strategy in a market economy where art is in absolutely no demand.

Perhaps the most telling statement is Aleksey Kallima’s installation “Scratch”. In the show, one only sees a scratch on a white wall, with a carpet knife lying on the floor in front of it – apparently the knife that cut the scratch.

In the main hall, there is a short video of Kallima cutting this scratch during the vernissage – hardly noticed by the surrounding people!

Only reading the catalogue, you learn that the artist had originally been commissioned to show an installation that contained, among other things, a picture of President Putin alongside human tongues – naturally, not real ones.

However, after the events of Sept 11, Kallima decided that he needed genuine human tongues, which were, of course, impossible to get.

Since the curators wouldn’t let Kallima show another work, he opted for a performance instead: he flew from Moscow to Berlin, equipped with a Koran and the carpet knife.

Here, you have it all: the outer form that looks like a sick joke, the innate political statement the artist desperately tries to make, the neglect he faces, and finally the rebellion against the art establishment, as personified in the German curators who tried to coerce the artist into a statement he didn’t want to make.

For the initial question remains: Is Davaj! anything to go by? The makers of the exhibition state their aim to give an overview over the contemporary “free”, i.e. “alternative” art scene, both in the two capitals and in the provinces.

To achieve this, they rely largely on the competence of local curators for their recommendations. What they came up with are artists who have already shown their work in large exhibition halls in Moscow, or in galleries abroad, or both.

Artists like Oleg Kulik, Anatoly Osmolovsky, or Dmitry Gutov have been around for a decade. Moreover, local references can hardly be found in the exhibition, and apart from the names, there is hardly any information on the artists.

Therefore the visitor is left with a puzzle which is probably not intended by the curators: Do the works have a value as autonomous works of art, or rather as ethnological exhibits?

The quality of many pieces is such that one is indeed rather tempted to treat them more as the after-effects of puberty than as artistic statements (my companion remarked that, had she stayed much longer, she’d have felt like a twelve-year old boy).

Their profoundly disturbing quality comes less from their shock potential (after all, we have come to expect epatage in a show of contemporary art), but rather from the knowledge of the reasons why the artists use those strategies.

Fittingly, the clue to the puzzle is not within the show, but on the group “Escape”‘s web page www.escapeprogram.ru.

A tourist, we learn here, is much like a lover of art at a museum: He finds beauty in everyday objects, frames them as art works, and relies solely on is his own gaze – unlike, and therefore superior to, the museum visitor, who relies on another’s (the painter’s). “Escape”, and Davaj!, are the tourist guides to these places.

What you find there, is up to you. Only be prepared that Davaj!, like any tourist agency, won’t lead you too far off the beaten track.

And by the way: the room in the left-hand side corridor that is shut by massive iron bars is the exhibition’s café.

(More images can be downloaded from: http://www.mak.at/service/c_service_presse.htm.)