Lost in Plain Sight: Dadaglobe Reconstructed

Dadaglobe Reconstructed, Museum of Modern Art, New York, June 12-September 18, 2016

Recently in art and exhibition culture, there has been a fashion for reenactment and reconstruction. Most pervasively – but also, in a sense, most naturally – this has occurred in performance art, notoriously when Marina Abramović shifted the stakes of scored performance from interpretive reiteration to faithful reenactment in Seven Easy Pieces (2005), a serial resurrection of seven historically important, but underdocumented performances.(See Carrie Lambert-Beatty, “Against Performance Art,” Artforum, May 2010, https://www.artforum.com/inprint/issue=201005&id=25443&show=activation, accessed November 10, 2016.) Equally, as Claire Bishop has pointed out, the reconstructive impulse has shown itself in reinstallation, where the original works tend to become “hybridized” for practical as opposed to conceptual or interpretive reasons: if materials available in past iterations ofthe work no longer exist, other more easily procured materials are substituted, forcing a salutary reinterpretation of the work that foregrounds its contemporary context.(Claire Bishop, “Reconstruction Era: The Anachronic Time(s) of Installation Art,” in Germano Celant, ed., When Attitudes become Form: Bern 1969/Venice 2013 (Venice: Fondazione Prada, 2013), 435-36.)

Exhibitions have also followed suit, most productively when they expand or adjust the presentation of the original, revealing chauvinist blind spots (as did Jens Hoffman’s globally extended Other Primary Structures in 2014 at the Jewish Museum), or when they call attention to critical differences between past and present (as did Germano Celant’s 2013 Venice Biennale reconstruction of Harald Szeeman’s Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form).(Hoffman’s intelligent reconstruction of Kynaston McShine’s 1966 minimalism show, Primary Structures: Younger American and British Sculptors, expanded the original exhibition’s scope globally. See Jens Hoffman, Other Primary Structures (New York: The Jewish Museum, 2014). Germano Celant reconceived Harald Szeemann’s 1969 conceptual art exhibition, When Attitudes Become Form, for a new context in the 2013 Venice Biennale, replicating the original location, Kunsthalle Bern, within a Venetian palazzo, thus emphasizing the status of the exhibition itself as a work of art. See Germano Celant, ed., When Attitudes become Form: Bern 1969/Venice 2013 (Venice: Fondazione Prada, 2013).) Spectacular or commercial motivations aside, the best outcome of these reconstructions is always the engagement of a productive dialogue between historical artistic and curatorial gestures and the most pressing issues of representation and exhibition today. Somewhere in the reconstruction the project must be made compelling, negotiating the urgency of recovering the original concept of the work with an acknowledgment of the impossibility of that task. Remembering is the first step; then comes rewriting that memory for the present.

Given the centrality of recall to reconstruction, how does one begin to assess an effort to retrieve a memory that never existed? This is the remarkable task that the editors and curators of Dadaglobe Reconstructed, the book and the exhibition, have undertaken: to “realize” a phantom project of the Dada impresario Tristan Tzara, an anthology of texts, portraits and original artworks meant to present the Dada movement at the apogee of its global effect. The project was set in motion in 2009 by art historian Adrian Sudhalter, who originally sought only to produce the book that Tzara never actually made. Her six years of research ultimately coalesced into an exhibition as well: Dadaglobe Reconstructed, which was first mounted at the Kunsthaus Zurich (February 5–May 1, 2016) and then traveled to the MoMA, New York. Working backward, in essence, from mysterious numbers she noticed on the backs of Dada works by a variety of artists in MoMA’s collection, Sudhalter traced the works to a single source: Tristan Tzara. From there, she cross-referenced a multitude of internationally scattered documents, including correspondence, planning lists, Dada journals, and works on paper. Sudhalter and her team (which ultimately included collaborators at MoMA, the Kunsthaus Zurich, and the Zurich-based design group NORM) have managed to produce an imaginative reconstruction of an important Dada text that has been, up until now, lost in plain sight.

The resulting publication and the traveling exhibition that developed out of the project communicates the global aspirations of the Dada movement as well as its internal fractures. The beautifully realized book, nearly sculptural in its appearance, is divided almost equally into two parts: a first, “hermeneutic” section, which includes essays by Sudhalter, Cathérine Hug (curator at Kunsthaus Zurich), Samantha Friedman (assistant curator at MoMA), a preface by Dada scholars Anne and Michel Sanouillet, a selection of primary documents, and a detailed illustrated checklist; and a second section, an imagined “facsimile” of the Dadaglobe publication itself.(Adrian Sudhalter, ed., Dadaglobe Reconstructed (Zurich: Kunsthaus Zurich; Scheidegger & Spies, 2016).) The two volumes are bound together out of necessity, in part as a reminder, as Sudhalter herself has emphasized, that the reconstruction straddles past directives and present realities: since the anthology had not been realized in Tzara’a lifetime, it bears the bias of hindsight in every gap that had to be filled in order to body it forth. For example, Tzara had determined the sequence of works, but hadn’t specified how they were to be juxtaposed on the page. He specified two common printing techniques for the illustrations – “lineblock” (for bold contrast) and “halftone” (for grayscale) – but decisions regarding layout, typography, and scale all had to be made “blindly” by the design team. Importantly, the first section of the book includes all of this information, serving as an interpretive guide for the anthology in its present form and as a map for the exhibition that grew out of the project. Without it, Dadaglobe as a reconstruction would have fatally lost its grip on context. By fusing the anthology with a record of the reconstructive process, Sudhalter has published a volume that serves not merely as artifact, but as model.

Sudhalter’s resurrection scheme stepped off from a carefully pieced-together description of Tzara’s original aims. The original Dadaglobe anthology began taking shape in late 1920, when Tzara, Francis Picabia (who seems to have been the financial backer), Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes and Walter Serner began soliciting contributions by mail from fifty artists and writers in ten countries. The book was to be between 160-300 pages, a mixture of images and text brought out by the mass-market Paris publishing house La Sirène in an uncommonly high edition of 10,000. With so large a print run planned (editions of 1,000 were more common), the title designation “globe” may well have been a reference to the projected distribution of the book, given that the reach of the movement was more accurately transnational – Tzara and his colleagues reached out of Western Europe only as far as Chile, Russia and Czechoslovakia, with most of the solicitations concentrated between France, Germany and the United States. The letters of invitation specified four categories of contribution: photographic self-portraits; photographs of artworks; original drawings; and designs for full pages of the anthology. These were to be mixed freely with texts throughout the book according to a systematic process meant to simulate random selection, reproducing in print the disruption that was the principal critical device of the group. The response was immediate and, with only a few exceptions (notably, Alfred Stieglitz and Richard Huelsenbeck), enthusiastic, drawing in more than 100 images and a thick folder of texts. Judging from the materials found in the Tzara papers at the Bibliothèque littéraire Jacques Doucet, production plans had progressed at least to the stage of determining the sequence and content of the pages before Picabia suddenly quit the Dada movement, pulled out of the project and Dadaglobe was abandoned. From this moment in 1921, Dadaglobe was never again mentioned in writing, and was long thought to be a mere hoax; another tongue-in-cheek Dada prank meant to throw ingenuous critics off the scent.(For these and all other details concerning the project, see Adrian Sudhalter, “How to Make a Dada Anthology,” in Dadaglobe Reconstructed (Zurich: Kunsthaus Zurich; Scheidegger & Spies, 2016), 22-68.)

Sudhalter’s resurrection scheme stepped off from a carefully pieced-together description of Tzara’s original aims. The original Dadaglobe anthology began taking shape in late 1920, when Tzara, Francis Picabia (who seems to have been the financial backer), Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes and Walter Serner began soliciting contributions by mail from fifty artists and writers in ten countries. The book was to be between 160-300 pages, a mixture of images and text brought out by the mass-market Paris publishing house La Sirène in an uncommonly high edition of 10,000. With so large a print run planned (editions of 1,000 were more common), the title designation “globe” may well have been a reference to the projected distribution of the book, given that the reach of the movement was more accurately transnational – Tzara and his colleagues reached out of Western Europe only as far as Chile, Russia and Czechoslovakia, with most of the solicitations concentrated between France, Germany and the United States. The letters of invitation specified four categories of contribution: photographic self-portraits; photographs of artworks; original drawings; and designs for full pages of the anthology. These were to be mixed freely with texts throughout the book according to a systematic process meant to simulate random selection, reproducing in print the disruption that was the principal critical device of the group. The response was immediate and, with only a few exceptions (notably, Alfred Stieglitz and Richard Huelsenbeck), enthusiastic, drawing in more than 100 images and a thick folder of texts. Judging from the materials found in the Tzara papers at the Bibliothèque littéraire Jacques Doucet, production plans had progressed at least to the stage of determining the sequence and content of the pages before Picabia suddenly quit the Dada movement, pulled out of the project and Dadaglobe was abandoned. From this moment in 1921, Dadaglobe was never again mentioned in writing, and was long thought to be a mere hoax; another tongue-in-cheek Dada prank meant to throw ingenuous critics off the scent.(For these and all other details concerning the project, see Adrian Sudhalter, “How to Make a Dada Anthology,” in Dadaglobe Reconstructed (Zurich: Kunsthaus Zurich; Scheidegger & Spies, 2016), 22-68.)

To my mind, the abrupt end of such a fully developed and enthusiastically greeted project remains the great, unanswered question of this reconstruction project. Why didn’t Tzara, who by 1921 held a trove of artworks that represented the core of the Dada project as imagined by its own practitioners, seek publication elsewhere? The works he solicited remained in his possession until they were dispersed at his death, landing mostly in museums in Europe and the United States. Sudhalter struggles to find an explanation, and theorizes that the publisher, La Sirène, may have closed down production because with postwar tensions between France and Germany so high, international collaboration drew too much attention from the authorities. Her evocation of postwar paranoia is compelling here, and gives specificity and complexity to the now standard idea that Dadaist irrationality rose out of the movement’s disgust with the nationalist politics and moral contradictions that led to the disastrous WWI conflict. Sudhalter describes in precise detail how obstacles to international movement and communication in this moment of heightened bureaucracy shaped the structure and content of the original Dadaglobe. The administration of national identity was underway, for example, with the development of a standardized passport system that required photographs and signatures in addition to identifying descriptors, and insisted on fastening individuals to a single nation-state. In the face of this political situation, Dadaglobe’s internationality alone issued a challenge to the prevailing xenophobic order, a sociopolitical climate that Roman Jakobson characterized as “zoological nationalism.”(Sudhalter, 64.) Mocking the officious demand to codify identity, Dadaglobe effectively declared itself a nation, and insisted that each of its “citizens” pledge allegiance by sending in their portrait. Naturally, many of these threw standards out of the window. And Dada resistance had material consequences: Dadaists traveled on borrowed passports and communicated by code in order to evade censorship and suspicion; certain Dada publications were issued twice, with French editions eliding German language contributions; police surveilled the number of foreign packages suddenly flowing into Everling and Picabia’s Paris apartment, and came calling; Tzara’s poetic doublespeak placed him under him suspicion as a spy against France. This context, as well, has been lost to accounts of the Dada movement, particularly Paris Dada (“Entente Dada,” as the German Dadaists sneered), and is one of the fascinating historical retrievals of the project.

Sudhalter’s realization of Dada’s lost book project is, I think, unprecedented. Re-editions, special editions and facsimiles are common in the publishing world; whole imprints are devoted to them, and they often take on an object-quality similar to that of Dadaglobe Reconstructed. But a full-on posthumous conjuring from fragments is rare, rather than expected, and I cannot think of a precedent in art publishing. But then Dadaglobe in its initial conception was an extraordinary project. Besides being, in Sudhalter’s words, a “significant catalyst for creation of new artworks,” Dadaglobe introduced a “new category of artistic production: artworks made for reproduction on the photo-mechanically printed page.”(Sudhalter, 23; 47.) The combination of text and image in these works and their exploitation of reproductive techniques to produce illusory effects point to Dada’s dawning understanding of the art book as a new space for display – a form of exhibition that combined intimacy and interactivity with mass distribution. Previously, this kind of paper exhibition space had been confined to documentary and scientific photography, and this may explain why Man Ray, who was only just learning to handle a camera, was quick to understand and embrace the possibilities of the form. That Max Ernst did, as well, including specific instructions to the printer for reproducing his collage Chinese Nightingale (1920) testifies to a widespread readiness for new forms of art that could evade the institutional confines of gallery space. From this point of view, mounting the project as an exhibition makes little sense, even when it appears in galleries devoted to prints and illustrated books.

For as Sudhalter herself pointed out in a related panel discussion, the Dadaglobe works are small and mainly monochromatic, and have little “wall power.”(“Lost Chapters of Modernism,” panel discussion at MoMA New York, September 13, 2016, https://www.moma.org/calendar/events/2265?locale=en.) Their “book on the wall” effect is deepened by MoMA’s dry, standard installation, which presents a staid march of images that tempers the internal turmoil of the individual works. Given that Tzara’s fundamental editorial gesture was to create “the appearance of ceded control,” the exhibition falls very far short of the overall spirit of the book, which was to appear “disorderly and unsystematic.” “There needs to be throughout a whirling, dizzy, eternal, new atmosphere,” Tzara wrote of Dadaglobe, “It should look like a great display of new art in an open-air circus. Every page must explode.”(Sudhalter, 56.)

For as Sudhalter herself pointed out in a related panel discussion, the Dadaglobe works are small and mainly monochromatic, and have little “wall power.”(“Lost Chapters of Modernism,” panel discussion at MoMA New York, September 13, 2016, https://www.moma.org/calendar/events/2265?locale=en.) Their “book on the wall” effect is deepened by MoMA’s dry, standard installation, which presents a staid march of images that tempers the internal turmoil of the individual works. Given that Tzara’s fundamental editorial gesture was to create “the appearance of ceded control,” the exhibition falls very far short of the overall spirit of the book, which was to appear “disorderly and unsystematic.” “There needs to be throughout a whirling, dizzy, eternal, new atmosphere,” Tzara wrote of Dadaglobe, “It should look like a great display of new art in an open-air circus. Every page must explode.”(Sudhalter, 56.)

With such a clear directive, and with the book itself in the process of materialization, the uninspired installation reads as a stunning missed opportunity. The history of dynamic exhibition spaces is as old as the avant-garde itself, and there are many historical precedents (including Berlin’s 1920 Dada Messe) that took the radical juxtapositions of mass media – the advertisement and the magazine page – as their models. Much could have been done here to communicate phenomenologically Tzara’s mandate to disruption and irrationality. Instead, unlike the book, which freely mixes genres, the curators chose to organize the works according to the categories Tzara had specified in his request (in Zurich, the works were organized geographically, an even more egregious violation of Tzara’s transnational intent). Materials that make strange and startling impressions on Dadaglobe’s printed pages seem wan and interchangeable on the wall. Where Sudhalter’s book design team made clever use of white space and typographical variation, and shifted the direction of texts so that readers are forced to turn the book this way and that in order to read the contributions, the exhibition installation made no effort to impress itself on the body of the viewer, or to generate the kind of confusion and irrationality Tzara intended for the book.

With such a clear directive, and with the book itself in the process of materialization, the uninspired installation reads as a stunning missed opportunity. The history of dynamic exhibition spaces is as old as the avant-garde itself, and there are many historical precedents (including Berlin’s 1920 Dada Messe) that took the radical juxtapositions of mass media – the advertisement and the magazine page – as their models. Much could have been done here to communicate phenomenologically Tzara’s mandate to disruption and irrationality. Instead, unlike the book, which freely mixes genres, the curators chose to organize the works according to the categories Tzara had specified in his request (in Zurich, the works were organized geographically, an even more egregious violation of Tzara’s transnational intent). Materials that make strange and startling impressions on Dadaglobe’s printed pages seem wan and interchangeable on the wall. Where Sudhalter’s book design team made clever use of white space and typographical variation, and shifted the direction of texts so that readers are forced to turn the book this way and that in order to read the contributions, the exhibition installation made no effort to impress itself on the body of the viewer, or to generate the kind of confusion and irrationality Tzara intended for the book.

Museum studies professor Bruce Altshuler has suggested that foregoing visual spectacle in favor of the kind of brainy, discursive approach typical of ephemera-heavy shows may be the onlyway for museums to remain socially relevant.(Bruce Altshuler, Biennials and Beyond: Exhibitions That Made Art History 1962-2002 (London: Phaidon, 2013), cited in Elitza Dulguerova, “Re-exhibition Stories,” Critique d’art No. 42, Winter 2013/Spring 2014, https://critiquedart.revues.org/13483?lang=en#ftn6, accessed November 10, 2016.) But giving attention to installation design that structurally communicates the main ideas of the works in question should not be mistaken for empty showmanship. Opting for a more dynamic, even claustrophobic installation might have helped communicate some of the contexts that Sudhalter so skillfully evoked in the book. The low-grade anxiety that reverberates through the first section of the book, for example – the sense that “the authorities” were hovering about the edges of the avant-garde, ready to pounce – is nowhere to be found in these clear and spacious galleries, and even resistance to the new “passport regime” that motivated the call for portraits has been overshadowed by the usual comments in the wall text about avant-garde “subversion” of the conventional categories of art production. Alternatively, the museum might have elected to emphasize the daunting number of works involved, reconstructing not so much Dadaglobe, the book, but the scene of its birth: Tzara’s own rooms, where the contributions were received and assessed.  In this case, the model could have been his own portrait contribution, a photograph in which he is depicted swamped by sliding piles of ephemera. The items seem, at first, too many and too alike to be memorable; but this impression is almost immediately followed by the sense that they are too intensely detailed and distinctive to be absorbed in a single viewing. Thus the first room, lined with a multitude of small portraits of varying interest (this category, as it turns out, drew the greatest response), soon reduces the viewer to skimming for something that catches the eye. This is a pity, since differently arranged, the images in this gallery – which amounts to a kind of Dada pantheon – might have itself communicated, through juxtaposition, the stranglehold of bureaucracy generated by the political context, particularly since we see so many unexpected figures here: Italians Julius Evola, Aldo Fiozzi and Gino Cantarelli, associated with the magazine Bleu, appear, along with military historian Alfred Vagts, and the Belgian writer Clément Pansaers (who expressed surprise at being identified as “Dadaist,” but sent in materials nevertheless).

In this case, the model could have been his own portrait contribution, a photograph in which he is depicted swamped by sliding piles of ephemera. The items seem, at first, too many and too alike to be memorable; but this impression is almost immediately followed by the sense that they are too intensely detailed and distinctive to be absorbed in a single viewing. Thus the first room, lined with a multitude of small portraits of varying interest (this category, as it turns out, drew the greatest response), soon reduces the viewer to skimming for something that catches the eye. This is a pity, since differently arranged, the images in this gallery – which amounts to a kind of Dada pantheon – might have itself communicated, through juxtaposition, the stranglehold of bureaucracy generated by the political context, particularly since we see so many unexpected figures here: Italians Julius Evola, Aldo Fiozzi and Gino Cantarelli, associated with the magazine Bleu, appear, along with military historian Alfred Vagts, and the Belgian writer Clément Pansaers (who expressed surprise at being identified as “Dadaist,” but sent in materials nevertheless).

Still, this kind of minutiae is an archivist’s dream, and its anti-spectacularity does afford a refreshing shift away from recent efforts to draw in mass audiences for splashy museum “experiences.” The origin story that Sudhalter has attached to Dadaglobe Reconstructed speaks directly to the subtle pleasures of the archive – the myriad, nearly unconscious ways that ephemera whispers to the astute researcher, whose intuitive “hunch making” rises from the countless images that pass before her eyes, such that when the “AHA” moment comes, it can’t necessarily be traced back to a single origin. This is the best reason to present the Dadaglobe photos and artworks themselves to the public, even if they were never intended for the wall.

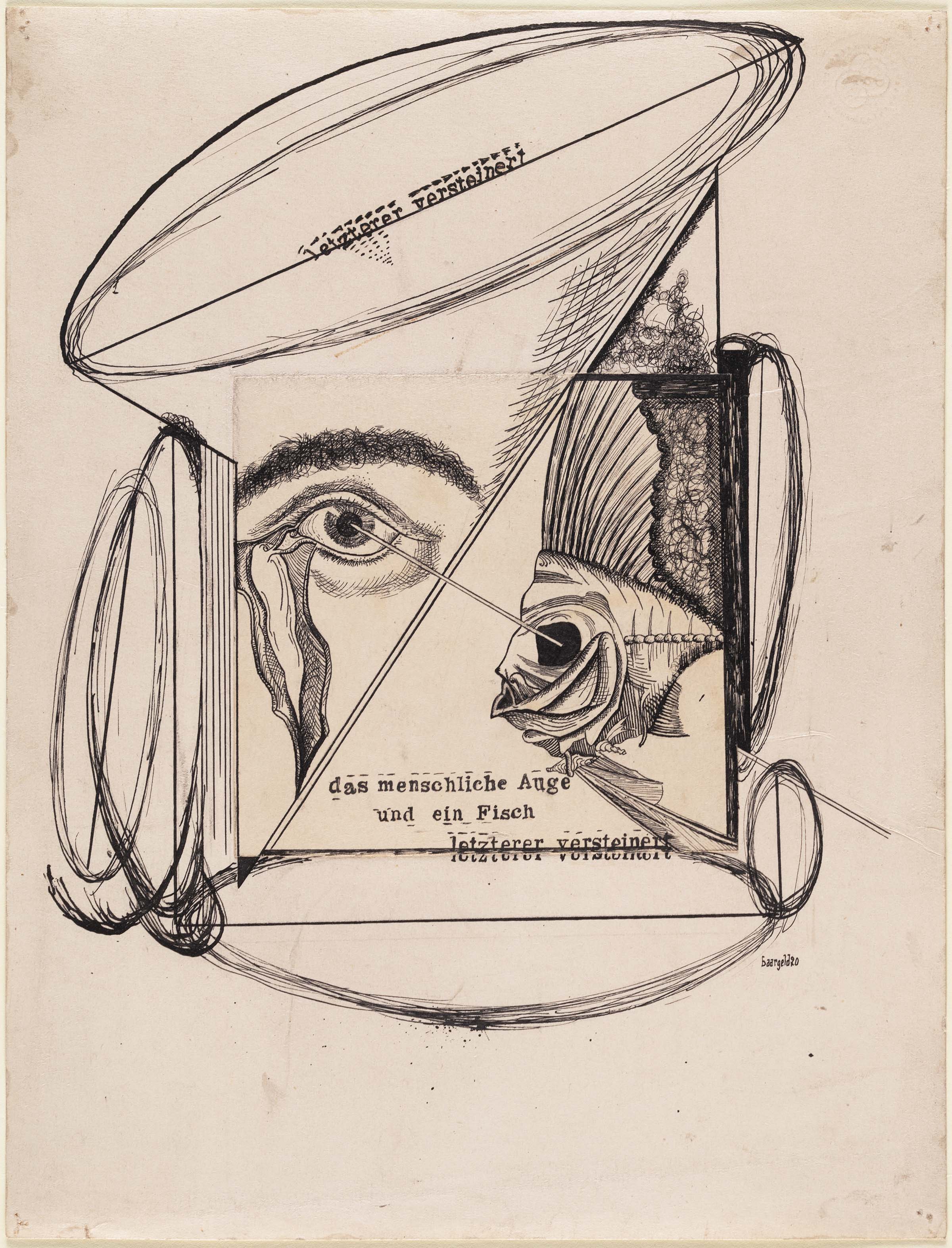

And there are many wonderful discoveries to be made in the galleries devoted to photographs of artworks, drawings and full-page designs: three images of “lost” works by Kurt Schwitters; a strangely absorbing typographic composition formerly claimed by Man Ray, here attributed to his companion Adon Lacroix; Arp’s tiny, appropriated image of a dog’s intestines, lightly retouched and renamed Laocoon, displayed here with the caption Arp intended for it. The full integration of works by women – Lacroix, Sophie Taeuber, Gabrielle Buffet-Picabia, Marguerite Buffet, Suzanne Duchamp, Luise Straus-Ernst, Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, Hannah Höch – attests to their centrality to the group. Likewise, the strong presence of undersung figures such as Ribemont-Dessaignes and Johannes Baargeld will force reassessments of the principal shapers of the movement through the sheer number of their contributions. While there are startlingly few photographs (portraits aside), some familiar ones take on new meaning in this context. For example, the Dadaglobe directive seems to have brought home to Man Ray the confusion of mediums typical of photography, and he here identifies and exploits it as something explicitly Dada. Is his photographic contribution, By Products (n.d.) an artwork with an overall composition, or is it a documentary photograph of a Dada installation: cigarette butts arranged according to the laws of chance?

And there are many wonderful discoveries to be made in the galleries devoted to photographs of artworks, drawings and full-page designs: three images of “lost” works by Kurt Schwitters; a strangely absorbing typographic composition formerly claimed by Man Ray, here attributed to his companion Adon Lacroix; Arp’s tiny, appropriated image of a dog’s intestines, lightly retouched and renamed Laocoon, displayed here with the caption Arp intended for it. The full integration of works by women – Lacroix, Sophie Taeuber, Gabrielle Buffet-Picabia, Marguerite Buffet, Suzanne Duchamp, Luise Straus-Ernst, Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, Hannah Höch – attests to their centrality to the group. Likewise, the strong presence of undersung figures such as Ribemont-Dessaignes and Johannes Baargeld will force reassessments of the principal shapers of the movement through the sheer number of their contributions. While there are startlingly few photographs (portraits aside), some familiar ones take on new meaning in this context. For example, the Dadaglobe directive seems to have brought home to Man Ray the confusion of mediums typical of photography, and he here identifies and exploits it as something explicitly Dada. Is his photographic contribution, By Products (n.d.) an artwork with an overall composition, or is it a documentary photograph of a Dada installation: cigarette butts arranged according to the laws of chance?

Spaced intermittently throughout the galleries, as if to acknowledge the inadequately engaging wall installation, the curators have included a handful of the artworks that the Dadaists photographed to include in Dadaglobe, among them, Taeuber’s Head (1920); Marcel Duchamp’s To be Looked at… (1918); Jean Crotti’s Mon autre moi (1920) and the remaining fragment of Constantin Brancusi’s Plato (1919-23), which help materialize the new constellation of works offered here, perhaps pointing toward a rearrangement of the Dada canon. While these inclusions raise productive comparisons between the private intimacy of the page and the public forum implied by the exhibition, foregrounding the ways the institution as a site comes to bear on the objects it encloses, they undercut the significance of Dadaglobe, the artbook as a new space of display, and the landmark status that its reconstruction represents. Unlike the book, this exhibition obscured the Dada forest for the trees: The movement’s hectic heterogeneity was tamed into an orderly rank-and-file that masked the anti-aesthetic institutional critique it activated, and along with it, the reasons to keep Dada in sight today.

Spaced intermittently throughout the galleries, as if to acknowledge the inadequately engaging wall installation, the curators have included a handful of the artworks that the Dadaists photographed to include in Dadaglobe, among them, Taeuber’s Head (1920); Marcel Duchamp’s To be Looked at… (1918); Jean Crotti’s Mon autre moi (1920) and the remaining fragment of Constantin Brancusi’s Plato (1919-23), which help materialize the new constellation of works offered here, perhaps pointing toward a rearrangement of the Dada canon. While these inclusions raise productive comparisons between the private intimacy of the page and the public forum implied by the exhibition, foregrounding the ways the institution as a site comes to bear on the objects it encloses, they undercut the significance of Dadaglobe, the artbook as a new space of display, and the landmark status that its reconstruction represents. Unlike the book, this exhibition obscured the Dada forest for the trees: The movement’s hectic heterogeneity was tamed into an orderly rank-and-file that masked the anti-aesthetic institutional critique it activated, and along with it, the reasons to keep Dada in sight today.