Locals Nowhere: Global Histories of Labor, Art, and Migration, Summer 2024

There is no there there, Museum of Modern Art Frankfurt (MMK), April 13 – September 29, 2024

Global contemporary exhibitions have invented a new conceit: they have begun to locate migrants everywhere and nowhere. Both There is no there there at Frankfurt’s Museum of Modern Art (MMK) and the 60th Venice Biennale “Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere” are evidence of this troubling development. Though this will primarily be a review of the exhibition at MMK, the Venice Biennale is a crucial point of comparison for understanding how contemporary curators are grappling with the quandaries of migration and place in art history. The poetic-sounding titles of both shows function as conceptual guises, which dress up the reduction of artworks to indexes of human geography. In the case of Venice, the title was lent from the eponymous neon signs made by Claire Fontaine since 2004 and implies, since foreigners are now everywhere, that there are no locals anywhere anymore.

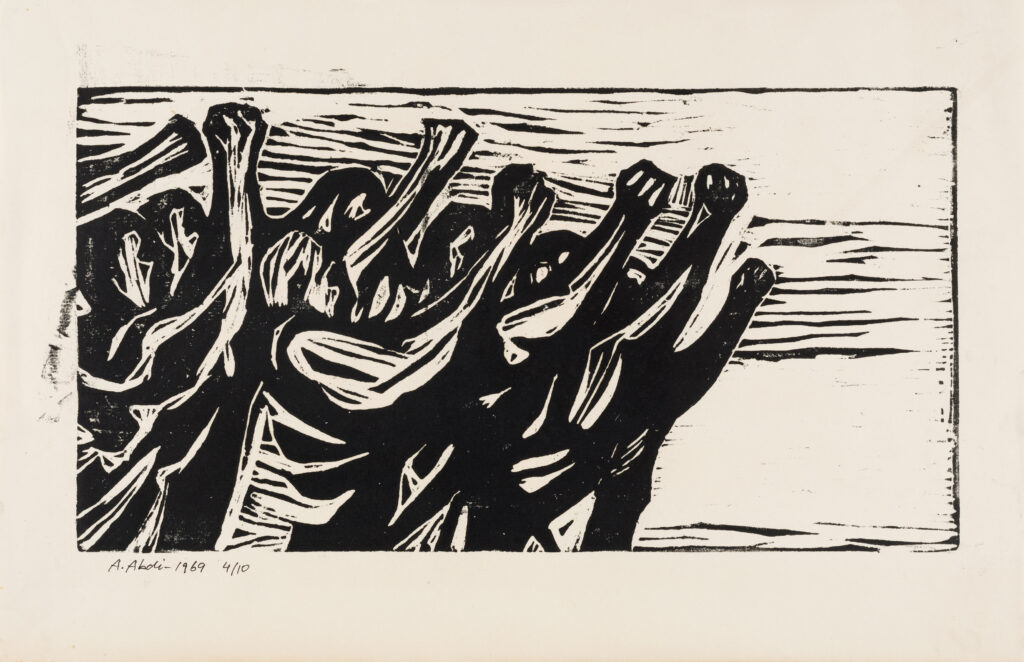

Abed Abdi, Demonstration, 1969, Collection Abed Abdi, Haifa (IL), © Abed Abdi, photo: Axel Schneider.

“There is no there there,” like a “nothing burger,” is often used to describe hollow legislation, retroactively identifying the policies that lured migrants to both Germanies as empty promises. However, in Everybody’s Autobiography by Gertrude Stein, the original context of the wistful line, it evokes the disorienting experience of being cut off from one’s memory of home upon returning there, similar to the “object-loss which has withdrawn from consciousness” from Freud’s theorization of melancholy.(Gertrude Stein, Everyone’s Autobiography (New York: Random House, 1937), 289; Sigmund Freud, “Mourning and Melancholia,” in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud (London: The Hogarth Press, 1953-74), 245.) The titles pit migration against place, unsettling, if not outright negating, the very vague deictic adverbs they put forth. If neither there nor everywhere, the only possibility left is nowhere.(‘There’ and ‘everywhere’ are almost opposites: ‘There’ locates a condition to a particular place or points to something just said, whereas ‘everywhere’ is antithetical to site-specificity, indicating ubiquity or commonality. While the negation of everywhere can be there, this is not true the other way around, the negation of there also negates everywhere. The only thing in common between the negation of everywhere and the negation of there is the possibility of nowhere.)

There is no there there presented work by thirty migrant artists who lived in East or West Germany in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s. Linked only by their destination, these disparate makers produced a great variety of works: installations, paintings, mask-like sculptures, satirical political comics, documentary films, and postcards, many of which thematize the experience of immigration and working in Germany. Like a pluriverse, far from a multicultural scramble, the exhibition is composed of discrete, but linked spaces with each artist filling an entire room or portion thereof. Rather than structure the exhibition by medium, geography or temporality, curators Gürsoy Doğtaş and Susanne Pfeffer rely on MMK’s playful postmodern architecture, designed by Hans Hollein, encouraging visitors to explore the exhibition in an associative, rather than unidirectional manner. The building’s hidden balconies, secret passageways, and half-story stairwells lead one to draw unexpected connections between artists, styles, and mediums that seem to stem from different worlds.

Artists in “Foreigner’s Everywhere” are allegedly linked, not by destination, but by an imprecise notion of movement (ranging from tourism to political flight) and ties to places – sometimes strong, sometimes faint – beyond where the artists reside. Venice intermixed works from the entire span of modernism and contemporary art, from as many geographical locations as possible. This maximalist strategy culminated in the deeply suspect “Italians Everywhere” corridor in the Arsenale, which lumped together the works of Italian émigrés who “became embedded in local cultures” elsewhere. Instead of tracking the movement of people as they spread out from a common origin, the ontology of diaspora, There is no there there brings together artists who traveled to and lived in divided Germany, united by the crucible of immigration. In this sense, the two shows are almost opposites. The MMK exhibition is far from perfect, but the perils in Venice reveal its achievements. A closer look at There is no there there will reveal how, far from simply reproducing logics of globalization, art made by immigrants in a specific context can scrutinize labor and the living conditions weighted against them.

The MMK exhibition employs the ambiguous phrase “artists from abroad” to sidestep the question of definitions, uniting people with widely variant socio-economic and political statuses. “[M]igrant workers, exiles, refugees, and ‘foreign workers’” are explicitly included alongside professional artists. These positions have nothing in common with the art world cast of ‘nomads’ and global elite, who can make pop-up experiments and choose home bases wherever. Instead, they contended specifically with the economic and social contexts of both Germanies, structured by the machinations of global capital and socialist government worker contracts. Overall, the main challenge of There is no there there is congealing a group of artists based solely on their immigrant status or foreignness to Germany. Can the negation of the German citizen serve as the basis for a different kind of group identity? Doğtaş and Pfeffer, MMK’s director, suggest that it can. By doing so, they put pressure on nomenclature, entrenched art world hierarchies, and even Cold War boundaries.

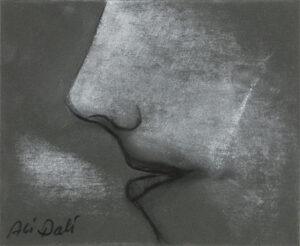

Ali Riza Ceylan, Untitled, n. d. (detail), © Private Collection, Cologne (DE), photo: Axel Schneider.

Ali Riza Ceylan, who, following in his father’s footsteps, emigrated from Turkey to West Germany in the late 1970s, was employed for multiple decades at Ford’s Body and Assembly plant in Cologne, where he made small, nearly monochromatic drawings on used sandpaper during breaks. By adding contour lines and accentuating volumes, he turns signs of wear on the paper into bodily fragments. One drawing depicts a heavily cropped face, reduced to an illuminated nose, subtly pursed lips, and a bloom of white beyond. His creative labor transformed the trace of manual friction into exhalation. If the conversion of labor into capital on the Ford assembly line demands the utmost control of bodily movement, Ceylan’s drawings subtly mark the obstinate gestures that elude instrumentalization.

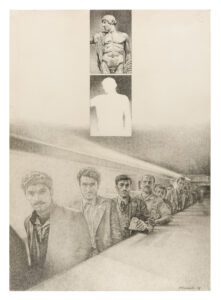

Jannis Psychopedis, Emancipation – a tribute to collector Ludwig, 1976; Migrants, 1978, Private Collection, Athens (GR), © Jannis Psychopedis, photo: Frank Sperlin.

Similarly, Jannis Psychopedis interrogates the grammar of labor by drawing bodily fragments. But unlike Ceylan, Psychopedis is a professional artist, trained at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich and later invited to Berlin by the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD). The series Seminars (1979-80) brings together small drawings that exaggerate West German aesthetics of consumerism with hand-written, smudged passages from Marx’s Capital. In another, portraits of migrant workers, some of whose silhouettes have been excised, contrast lewd, nearly pornographic portraits of white Germans. In a third work, Migrants (1978), proletarian men line-up, papers ready, as if waiting for an official stamp or job offer. Floating in space above them, there is an enigmatic vertical bar depicting a marble nude and its silhouette. The axes bring together two resources from Greece that play a major role in German society but are rarely thought together: classical aesthetics and contract workers. Altogether, the various juxtapositions, ghosting of migrants, and removal of clothing stage a collision between different techniques of disclosure and concealment: erotic play, desire, and the construction of beauty, on the one hand, and the oppressive state mechanisms that make migrant workers invisible on the other.

Jannis Psychopedis, Migrants, 1978, Privatsammlung (GR), photo: Axel Schneider.

While some of the immigrants in the exhibition were professional artists, beckoned to Germany by art education and prestigious fellowships, others were contract workers who came to Germany for industrial labor, making art in their free time. At points, the exhibition can feel overly eclectic, with artists breaking off into their own domains. There are more than a few free-standing wall-like implements in the exhibition, intended to glide attention towards adjacent works, that leave visitors awkwardly adrift. Further, for an unfavorable viewer, the great variance in the professional trajectories of the artists presented may seem to produce an unfair playing field, revealing differences in drawing dexterity or available time. More generously, the exhibition challenges the hierarchy between artists who gain self-consciousness of their efforts as acts of labor (approaching but not quite identical to Julia Bryan Wilson’s notion of the “art worker”) and workers who are also artists.(Julia Bryan-Wilson, Art Workers: Radical Practice in the Vietnam War Era (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011). For Bryan-Wilson, art workers were artists who participated in or directly interacted with the Art Workers’ Coalition. In a more expansive sense, the term could also refer to politicized artists who, informed by the history of conceptual art, began to interrogate the conditions of artistic production vis-à-vis labor movements.) These hobbyists, it turns out, do just as much critical reflection on labor as the art worker.

An analogous case to Ceylan is the Mozambican contract worker Dito Tembe, who, like many others, traveled to East Germany as part of so-called “solidarity agreements,” but was never adequately compensated for his labor.(Many Madgermanes, people from Mozambique who lived and worked in East Germany, have yet to receive their full salaries and still protest, to this day, in Maputo.) Between 1985 and 1989, he worked at a leather factory in the regional capital Schwerin, attending an art course and painting outside shifts. As a tribute to the female heroes of Mozambique’s civil war, he painted the Woman on the Front Line in his residence. Since lost, Tembo reproduced the mural at the apex of MMK for the exhibition. The graphic language and revolutionary enthusiasm employ a distinctly East German formal language, sending an unambiguous message of spirited militantism.

Dito Tembe, Frau an die vorderste Front (Woman on the Front Line), 1986/2024, courtesy of the artist, photo: Frank Sperling.

Rimer Cardillo, Installation View MUSEUM MMK, photo: Frank Sperling.

Similarly, prints by the Uruguayan artist Rimer Cardillo, who studied art in Berlin and Leipzig, show how foreign students adopted East German forms for their own goals. The collaged photographs of cicadas, staccatos of black and white punctuated by red, are reminiscent of John Heartfield’s photomontages, but in the early 1970s, the beginning of the Honecker era and military dictatorship in Uruguay, combative political messages of the earlier times have turned inward, made cryptic. Like cryogenic troops, the bugs standby, waiting for just the right moment to shed their exuviae. The Palestinian artist Abed Abdi, trained at the Fine Arts Academy in Dresden, also demonstrates that foreign students activated socialist iconography. Demonstration (1969), a woodblock of an uprising – fists raised high – is curiously tucked into a small and unusually cold room on the second floor, as if shouting from a muffled corner. Through Abdi, one can recall how the diffuse sentiment of anti-imperialism, percolating throughout global socialism’s print culture, also crystallized into pointed aims, like the liberation of Palestine.

One of the greatest strengths of There is no there there, and perhaps also its most provocative move, are the soft contours it draws around East and West Germany. Nowhere does the exhibition indicate “here are artists from the West, here from the East.” The viewer must think about why such distinctions matter from the perspective of immigrants. Examples from both countries demonstrate that immigration led to the adoption of German forms, bent towards new goals. In West Germany, immigrant artists utilized current West German artistic impulses, such as the language of conceptualism or efforts to de-sublimate society, to challenge the conditions of labor and white hegemony. In East Germany, because open critique of the state was stymied, artists used locally acquired socialist forms, descendants of socialist realism and agitprop, to express support or dissent for struggles in their home countries. Although these two vectors may seem to move in opposite directions spatially – inward and outward – both are instances of migrants wielding art against oppressive state structures.

Abed Abdi, Sea Silence; Demonstration, 1969, Private Collection, Haifa (IL), © Abed Abdi, photo: Frank Sperling.

This returns us to the 60th Venice Biennale, where, ironically, the nation was reconsolidated in pseudo-leftist terms. “Italians Everywhere” jumbled together single works by Italian émigrés without regard for underlying push-and-pull factors, artists’ political commitments, or contextual cues about their chosen forms. Aside from the pairing of artists with similar destinations, there was nothing to bind works together. In the hall, they were so thematically and stylistically divergent that they became mere evidentiary documents of international travel, like a smattering of passport stamps. No wonder, the provenance and shipping labels on the versos, cunningly made visible by Lina Bo Bardi’s concrete-and-glass support pedestals, became more captivating than the rectos. Neither narrating an art historical trajectory nor tarrying with a common political experience, say, the challenges of emigration, the works were reduced to a mere inventory of geographic nodes, the kind familiar from airline hub maps: Italy-United States, Italy-Ethiopia, Italy-Argentina.

On one hand, “Italians Everywhere” claimed an elusive sense of Italian-ness, the kind that can be savored by international tourists on summer holiday, marketed globally by businesses like Eataly, and stamped with authenticity – D. O. P.(D.O.P. is an abbreviation for “Denominazione di Origine Protetta” (Protected Designation of Origin), a special economic status established by the European Union to assign value and protections to specific products based on their geographic origins.) On the other, the inventory did just the opposite: it proved that nothing holds the artworks together besides the fact that all the makers began life on the Apennine Peninsula. In other words, the inventory spoke with a forked tongue: it undid Italy’s boundaries and, in an uncritical way, celebrated ambivalent concepts like foreigners and movement (just consider colonialism, tourism, airline pollution, and fascists fleeing to South America to escape war tribunals to recognize the negative potentials of these terms). It promoted cultural pride, the kind that can appeal to Meloni’s neo-fascist agenda. Thus, the foreign, which, in other parts of the Venice Biennale and There is no there there, genuinely challenges the state, was reconciled with the former institution’s foundational goal: to celebrate national cultures. For a long time, the local has been an icon of everyday fascism. Knowledgeable and deeply rooted in a place, but also xenophobic and threatening towards people from elsewhere. The Venice Biennial represents a marked shift of this formula: global contemporary art has so drastically diluted the foreigner that the figure can now be donned by the right, while it forcefully implements anti-immigration policy. Amidst the smokescreen, art and visual form drop out the back door. “Italians Everywhere” did nothing to explain the impact of migration on art history, or, vice versa, what art can uniquely communicate about the experience of immigration.

While the Venice Biennial simply negated the state from the start, by artificially mixing everything to the point that local and foreign lost their intrinsic opposition, to ultimately let nationalism divorced from the state sneak in the backdoor, the MMK exhibition began with two Germanies, selecting works that make visible the structural limitations imposed on migrant workers, to ultimately challenge the existence of states as given facts. In more ways than one, There is no there there is the antithesis to “Italians Everywhere.” Rather than simply negate the state by affirming the global movement of people in every direction, the MMK exhibition examined how migrants can critically challenge domestic and international governance from the specificity of one single place.