Laibach: The Instrumentality of the State Machine

Laibach and NSK analyze nationalism through the aesthetic dimension. By placing “national and subnational” symbols alongside each other, we demonstrate their “universality”. That is, in the very process of one nation defining its difference against the other, it frequently uses the same, or almost the same, kind of symbols and rhetoric as the other.

(–Laibach, from on-line interviews)

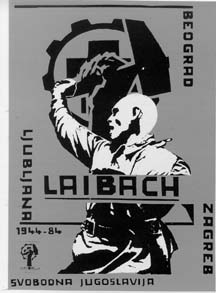

Laibach is a musical group that first began performing in the mining town of Trbovlje in central Slovenia in 1980. With Tito’s death that year, the future of Yugoslavia became uncertain, and throughout the 1980s youth subcultures engaged in agitation in the sphere of civil society producing challenges to the existing Socialist government. In using the term civil society, I refer to social interaction on all levels: institutional, private, public, etc., which involve aspects of self-involvement and social relations more regulated by laws and institutions. By subject I refer to the subject of psychoanalysis who is always split from his/her object of desire and whose actions represent this eternal longing for wholeness which can never be fulfilled.

In 1984 Laibach merged with similar artistic groups working in the Slovene capital city of Ljubljana to form the art collective Neue Slowenische Kunst, NSK, (New Slovene Art). The art collective NSK comprises the groups Laibach (music and ideology), Irwin (fine arts),Noordung (theater), and New Collectivism (graphic arts). The art collective shifted its strategy in 1992 by becoming a “state”, the “virtual state” of NSK. Laibach are the founding fathers of the NSK art collective and virtual state, having created the aesthetic strategies and materials characteristic of all NSK work. The members of the collective of NSK function on the level of voluntary rejection of personal tastes and individuality, opting to work as cogs in the machinery of a larger, anonymous, collective body.

I want to discuss the post-punk, industrial music band Laibach in terms of their aesthetic use of the symbols and rhetoric of totalitarianism and nationalism. By exploring this aesthetic in terms of the social situation in which Laibach developed (1980s Yugoslavia), I want to map the overarching elements of Laibach’s critiques of the interrelatedness of art and politics which are of continued importance for the situation today in the wars that followed the disintegration of Yugoslavia. While I view Laibach to be an important artistic movement in relation to the overall social structures of Europe, regardless of East-West divisions, for the purpose of this essay, I focus most specifically on the Balkan context and issues relating to war, politics, violence and art.

Laibach’s aesthetic strategy of staging “constructions” of violence and state power involves the manipulation of reactions of fascination and fear, seduction and repulsion and the subject’s desire to remain a passive receptor, the role most commonly adopted by the the audience of entertainment. Laibach use well-known, recognizable symbols and rhetoric to lure the spectator into a preconceived assumption relating to the symbols and rhetoric found within Laibach’s work. The German Fascist, Nazi element of Laibach’s symbols are often the first to be recognized, to the extent that they are arguably some of the most easily identifiable components of Laibach’s style. Within their earlier work especially, Laibach frequently incorporated images such as swastikas, the fascist leader berating or addressing the crowd, staging concerts resembling mass nationalistic rallies. LaibachKunst often appeared as thinly disguised reproductions of Nazi-Kunst. In the collective’s biography, NSK, Laibach declare that their manipulations rely on the signs and techniques associated with “Taylorism, bruitism, Nazi Kunst and disco,” (NSK, 18).

Laibach’s aesthetic strategy of staging “constructions” of violence and state power involves the manipulation of reactions of fascination and fear, seduction and repulsion and the subject’s desire to remain a passive receptor, the role most commonly adopted by the the audience of entertainment. Laibach use well-known, recognizable symbols and rhetoric to lure the spectator into a preconceived assumption relating to the symbols and rhetoric found within Laibach’s work. The German Fascist, Nazi element of Laibach’s symbols are often the first to be recognized, to the extent that they are arguably some of the most easily identifiable components of Laibach’s style. Within their earlier work especially, Laibach frequently incorporated images such as swastikas, the fascist leader berating or addressing the crowd, staging concerts resembling mass nationalistic rallies. LaibachKunst often appeared as thinly disguised reproductions of Nazi-Kunst. In the collective’s biography, NSK, Laibach declare that their manipulations rely on the signs and techniques associated with “Taylorism, bruitism, Nazi Kunst and disco,” (NSK, 18).

Taylorism reflects the industrial mode of production based on notions of mass production and efficiency. Bruitism is a reference to the artistic and philosophic movement which represents the exploitative relations within society in its most basic and brutal form. Nazi-Kunst exemplifies perfectly the interrelatedness of art and politics. Disco and “disco rhythm as a regular repetition [are] the purest, the most radical form of the militantly organized rhythmicity of technicist production, and as such, the most appropriate means of media manipulation,” as explained on a spoken address from the album Rekapitulacija, 1980-1984.

Laibach use ideologically charged symbols which effectively function to address the subject’s desire to belong to a community, most notably the nation. This desire, (often unconscious,) seeks symbols that represent points of identification within ideological systems. These symbols can often refer to problematic, totalitarian state systems, such as Nazism, Stalinism. The use of the German language and the choice of the German name “Laibach” further encourage an association with German fascism and Nazism. “Laibach” has taken on the German name of the Slovene capital city, Ljubljana, to recall specific historical periods and the traumas associated with these periods; the reign of the Austro-Hungarian empire, fascist occupation during the Second World War, essentially periods ofoccupation, resistance and/or collaboration. The members of the group chose the name “Laibach” for a youth movement aiming to manipulate art and ideology by means of industrial music with a single purpose in mind: to provoke the audience by inciting associations with past traumas.

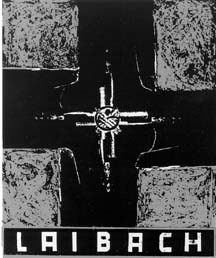

In early 1983, as Laibach gained recognition and became much more visible within the former Yugoslavia, the use of the name “Laibach” was outlawed. Laibach were not allowed to appear in concert under the name “Laibach,” but the band continued to perform concerts announced through posters invoking Kassimir Malevich’s Suprematist image, the Black Cross. Radio announcers would discuss a concert to be given at a certain place and time, never announcing the band by name, but playing the music in the background during the announcement. By forbidding the use of the name, the state effectively recognized the communicative nature of the name and the presumed danger in its connotations. Laibach responded with the statement “our name might be dirty, but we are clean.”

In early 1983, as Laibach gained recognition and became much more visible within the former Yugoslavia, the use of the name “Laibach” was outlawed. Laibach were not allowed to appear in concert under the name “Laibach,” but the band continued to perform concerts announced through posters invoking Kassimir Malevich’s Suprematist image, the Black Cross. Radio announcers would discuss a concert to be given at a certain place and time, never announcing the band by name, but playing the music in the background during the announcement. By forbidding the use of the name, the state effectively recognized the communicative nature of the name and the presumed danger in its connotations. Laibach responded with the statement “our name might be dirty, but we are clean.”

Although Laibach use rhetoric and symbols of Nazism, there is an inconsistency within their use that reflects a subtle play involved with an image or statement. Laibach play on the Third Reich’s propaganda statement “one transmitter and a multitude of receivers,” a reference to the manipulative potential of the mass media. Early on, Laibach declared themselves to be members of the first television generation, denouncing rock music as totalitarian in nature. They rejected the conventional belief in the revolutionary potential and freedom of rock music and the subcultures associated with it as a misrecognition of the continued dominance of the market economy and sanctioned outlets for the expression of energy and rage. Rather than changing much within the social structure, they hold that rock music invariably serves as a safety valve of acceptable rebellion which actually helps to preserve the dominant social structure.

In Laibach’s view, rather than representing an arena of freedom and escape from ideology, pop music and rock and roll mirror the relations of domination and power within society. Laibach’s references to totalitarian state power may refer to a different symbolic system, but rock and roll is the same phenomenon in terms of libidinal economy. In performance and rhetoric, Laibach celebrate the hero, the warrior, the male body, politics as spectacle, control and submission. The song “Ti, Ki Izzivas” (“You Who are Challenging”) evokes the war hero, ready to die for the cause. In the background music, the music from the shower scene in Hitchcock’s Psycho hints at the implications of psychotic fascination, the eroticization and libidinal investment in death and military heroism.

TI, KI IZZIVAS

Ti, ki izzivas

vsaj ne sili v kritje;

to ni velikega poguma znak

Srcno stopi sam

v drvoprelitjein padi,

CE SI ZARES JUNAK!

(YOU WHO ARE CHALLENGING)

You, who are challenging

at least do not look for cover

It is no sign of great courage

Go out yourself, in manly fashion

to the slaughter – and die

IF YOU REALLY ARE A HERO!

Laibach adopted the military clothing and bombastic music in recognition of its power to hold sway over an audience. The expression of power and force at the concerts, symptomatic in the outer military appearance of the group, antlers and banners placed on stage, reflect the overarching theme of Laibach’s work: the nature of power and the interconnectedness of politics, ideology and art.

The swastikas found in much of Laibach’s visual imagery are actually derived from a John Heartfield montage of four blades bound together to form a swastika with blood dripping from the blades. These images are direct references to John Heartfield’s anti-fascist photomontages of the 1930s. Other uses are more difficult to decipher. In 1933, Josef Goebbels stated that politics is “the highest and most comprehensive art there is and we who shape modern German policy feel ourselves to be artists.” This statement is juxtaposed with the Laibach statement, “[p]olitics is the highest and all embracing art, and we who create contemporary Slovene art consider ourselves politicians,” (NSK, 48).

The swastikas found in much of Laibach’s visual imagery are actually derived from a John Heartfield montage of four blades bound together to form a swastika with blood dripping from the blades. These images are direct references to John Heartfield’s anti-fascist photomontages of the 1930s. Other uses are more difficult to decipher. In 1933, Josef Goebbels stated that politics is “the highest and most comprehensive art there is and we who shape modern German policy feel ourselves to be artists.” This statement is juxtaposed with the Laibach statement, “[p]olitics is the highest and all embracing art, and we who create contemporary Slovene art consider ourselves politicians,” (NSK, 48).

The mythical narratives created by nations to make sense of and revise their perceived relation to the past, present, and future constitute another element that is re-articulated in Laibach’s work. One of the most developed national myths of post World War II Slovenia has been the myth of Slovenia as an inherently anti-fascist, anti-Germanic nation, having been the first region to successfully turn back fascist invaders in World War II. The elements of truth within this historical narrative are overshadowed by nationalistic fervor, which itself is very similar in structure to fascism. In the film on Laibach and NSK entitled Predictions of Fire (1995), the philosopher Rostko Mocnik explained that fascism persisted during Real Existing Socialism within Yugoslavia and continues to flourish because, “the confrontation with fascism was never really made on the symbolic level. It was clear for the rest of the Eastern Bloc that it couldn’t happen, it was too close to the ways totalitarianism functioned there. While in Yugoslavia, I guess it happened for a perverted reason, namely, the real victory over fascism, the military victory blocked the symbolic continuation. People thought it was OK. ‘We defeated the Nazis. We defeated the Quesnicks. We don’t have to worry about them anymore.’ And of course, the everyday fascism is always there without the Quesnicks and the Nazis.”

Laibach’s symbolic manipulation of particularly fascistic symbols and rhetoric challenged the notion that these ideas were not possible within, or a threat to, Yugoslavia. They exposed them in the everyday social sphere and brought back traumatic memories and associations. In their concerts, Laibach stage an assault on the audience and a frustration of its expectations, offering a Brechtian challenge to the desire for catharsis and entertainment. The audience is often forced to wait a lengthy time before the show begins. The lights are then turned on, often directly pointed at the audience, as though the audience were the true spectacle and subjecting its members to a sense of interrogation and expectation. After a long wait, there then begins a (usually taped) drum introduction or pounding instrumental techno rhythm. The result is increased expectation, agitation, growing crowd hysteria and anger. The continued loud rhythm produced by drums or synthesizers creates an effect similar to shell shock within the audience, preparing the audience for the “psycho-physical” assault of terror that is the Laibach “sound creation:” “Laibach practices a sound force in a form of systematic psycho-physical terror as socio-orgaizational principle in order to effectively discipline and raise a feeling of total adherence bond of a certain revolted and alienated audience which results in a state of collective aphasia, which is the principle of social organization.” (Rekapitulacija, 1980-1984)

While the spectator can feel drawn to the performance as a whole as it is staged before him or her, he or she may also feel an uneasy sense of guilt in observing what Laibach puts forth as performance or entertainment. While s/he is caught up in the music, the experience is exhilirating. After the music stops, a sense of awkwardness spreads over the crowd. The awkwardness results from the spectator’s realization that s/he has been deceived through a manipulation of his or her desire. This deception has resulted in an identification with an “undesirable” form of nationalism to which s/he had previously considered him/herself immune.

This deception reveals more about the audience’s hidden desires than about the band’s own intentions or personal beliefs. For people to be deceived, they must want to be deceived. Often the uneasy feeling is associated with pure anger, violently directed towards Laibach. To properly address the issue of desire, that is, the desire for a sense of belonging and community and within collective, national, ideological structures, desire has to be read not so much as a desire for pleasure or pleasurable experiences, but rather as a desire for fantasy. It is fantasy which structures our desires, providing meaning to our lives within the social body.

Within fantasy there is an object of fantasy, providing meaning through the subject’s relation to the object of fantasy. The subject knows his or her role through processes of identification, whereby the subject is fortified through an identification with someone or some group other than him/herself. Similar relations of desire reflected through social relations provide a positive identification. Interpellation of the subject is the process by which an individual recognizes him or herself as a member of a community or group. Belonging to a group or community implies certain identity behavior and attitudes. In his essay “Ideology and the State,” Louis Althusser explains that the nature of identity formation has a mirror – like structure. The specular quality of the subject’s identity formation is double, itself reflecting the manner in which ideology functions and can be assured to function. Through the unconscious mechanism of an individual conforming him- or herself to belong, mirroring the attitudes and behaviors of the social body, the continuation of the system is ensured.

Within fantasy there is an object of fantasy, providing meaning through the subject’s relation to the object of fantasy. The subject knows his or her role through processes of identification, whereby the subject is fortified through an identification with someone or some group other than him/herself. Similar relations of desire reflected through social relations provide a positive identification. Interpellation of the subject is the process by which an individual recognizes him or herself as a member of a community or group. Belonging to a group or community implies certain identity behavior and attitudes. In his essay “Ideology and the State,” Louis Althusser explains that the nature of identity formation has a mirror – like structure. The specular quality of the subject’s identity formation is double, itself reflecting the manner in which ideology functions and can be assured to function. Through the unconscious mechanism of an individual conforming him- or herself to belong, mirroring the attitudes and behaviors of the social body, the continuation of the system is ensured.

By making the means by which this function operates become obvious, the continuous repetition of identification and further fortification of the structure can be weakened or destabilized. Althusser concedes that for ideology to function properly, reality is necessarily misrecognized (méconnue) within the various forms in which the subject recognizes him or herself. Therefore, ideology has an inherent aspect of misrecognition and ignorance on the part of the subject. Laibach make the repetitive character of socially dominant power structures apparent and show the rituals of social identification and the desires associated with them to be senseless rituals followed in a necessarily non-reflective manner.

Longing to belong to the mass implies a desire for belonging within the ideological structure of a ruling system. Within the mass of the community, the individual can lose him or herself and feel euphoria through collective power. The song “Sila” (“The Force”) addresses these feelings of collective euphoria oriented towards state power, unity and force.

SILA – THE FORCE

(1982)

Tempests are roaring over us.

Cities and bodies are burning!

We are shaken by delight.

The sounds of our speech are spreading

Wide over the fields,

A speech that is our prayer and our cry.

No, never again, you universal God,

Will you let our force be submerged,

For it is so infinitely sweet and profound…

We are shaken by delight!

Laibach combines familiar negative symbols and rhetoric (swastikas, extreme violence, glorification of death) with equally familair, more neutral symbols and rhetoric (antlers, the command to love your fellow man) in what Slavoj Žižek terms an “inconsistent mixture, inconsistent bric-a-brac”. In this manner, Laibach manipulate the sensation of both repulsion and fascination. In the early 1980s, Laibach assumed the outer appearance of state authority (quasi-military uniforms, discipline, perfection and order) to which most Yugoslavians were conscious of the appropriate level of patriotism and responsibility they were to feel as citizens.

Laibach combines familiar negative symbols and rhetoric (swastikas, extreme violence, glorification of death) with equally familair, more neutral symbols and rhetoric (antlers, the command to love your fellow man) in what Slavoj Žižek terms an “inconsistent mixture, inconsistent bric-a-brac”. In this manner, Laibach manipulate the sensation of both repulsion and fascination. In the early 1980s, Laibach assumed the outer appearance of state authority (quasi-military uniforms, discipline, perfection and order) to which most Yugoslavians were conscious of the appropriate level of patriotism and responsibility they were to feel as citizens.

Rather than assuming an apparently critical distance to thematize actual state corruption in comparison to its idealistic nationalistic rhetoric, Laibach represent the state where “[t]he state behaves as we do. This is a dialectic dialogue, traumatic for the people,” (NSK, 60). Laibach reiterated the party line and followed all the ideological imperatives to their necessary conclusion. Rather than embodying an approriate level of patriotrism and loyalty, Laibach took it all too seriously, thereby overidentifying with the state. In so doing, they exposed the dangerous of what total devotion to state and nation imply far more effectively than parody or humor might appear to be able to effect. As with the prohibition of the name “Laibach,” the state continually engaged Laibach, taking them seriously, in effect giving them the power they had to affect the structure of the state.

Laibach incorporated taped political speeches into their performances and recordings. Early on, in particular, the speeches of Marshall Josip Broz Tito were incorporated to thematize the Yugoslav natonalistic rhetoric of unity and brotherhood and the defense of the nation from external or internal threats. The song “Drzava” (“The State”), incorporates a quote spoken by Tito which proclaims: “We have shed a sea of blood for the fraternity and unity of our nations. We shall allow noone to inerfere or plot from within to destroy this fraternity and unity.” The rhetoric of unity at any cost mixed with the lyrics “all freedom is allowed, authority here belongs to the people” results in a contradictory message:

DRZAVA-THE STATE

(1982)

The state is responsible for

The protection

Elevation

And exploitation of the forests

The state is responsible for

The physical education of the people

Particularly of the youth

In order to raise the standard of national health,

Labour

And defense potentials

It is becoming more and more lenient

All freedom is allowed

Authority

Here belongs to

The People!

In The Spoils of Freedom (Routledge, 1994), Renata Salecl addresses just such a contradiction within the structure of self-management in the former Yugoslavia. The collision of the rhetoric of unity with ideas of plurality in self-managment as developed in the 1970s resulted in “[s]omething which, at first glance, seemed to be just another empty phrase from the self-management vocabulary, …[which] suddenly turned out to generate a multitude of interpretations and thus to mark a site of radical contingency….So an apparently surplus syntagm became the point at which the system began to fracture. This is the point where elements, which had until then formed the ideological structure, now achieved independence and began to function as ‘floating signifiers’ awaiting new articulation, (61, 62).” Laibach were actively involved in the manipulation and rearticulation of these ‘floating signifiers.’

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Laibach incorporated speeches in their concert performances which had been written and performed by the representative of NSK’s Department of Pure and Applied Philosophy . These discourses reworked speeches by Slobodan Milosevic performed in a mixture of the Serbian and German languages. Neville Chamberlain’s words of appeasement to Adolf Hitler on the issue of his annexation of lands to the east of Germany were used to conclude the speech given in Belgrade, 1989. Images of war and destruction were projected onto screens with the symbol of NATO superimposed over most of the images.

These speeches, given in 1989 in both Belgrade and Zagreb, served to succinctly predict and warn of the coming wars in the Balkans and the rhetoric which would later accompany the concentration camps and ethnic cleansing. Nationalistic fervor within Serbia was provoked and controlled by Serbian television broadcasting of war time footage from the Second World War which portrayed Slovenia and Croatia as Nazi sympathizers and collaborators. The war footage was musically accompanied by the Serbian military march from World War I about military advances along the river Drina .

During the NATO tour, Laibach performed in Sarajevo, a city destroyed by the war in the Balkans, and performed its version of the war march, “Mars on River Drina,” at the National Theater in November, 1995. Laibach performed this song, which thematizes the horror of war (“Mars” denoting both the god of war and “march”) and the manipulation of national memory and trauma to garner the support of the military, while the heads of the various splinter states of the former Yugoslavia signed the Dayton Peace Accord which would allow NATO troups into Bosnia.

In the early performances, Laibach incorporated an overidentification with the totalitarian state structure of the former Yugoslavia. Current Laibach manifestations and cultural productions continue to combine a strict adherence to discipline and state authority, but now also engage the fundamentalist religious ritual which has increasingly become a primary cause of violence within the Balkans. During the Jesus Christ Superstars tour, the lead singer dressed more like Jesus with long hair and a beard, with a large cross necklace. This Christ-like appearance is, on the outside, much different from the shaved head and military uniform of previous tours. The other band members dressed in black with priests’ collars during the Jesus Christ Superstars tour, in contrast to their usual bare chests or brown shirts and black ties. Either “uniform,” representing religious or political devotion, serves to ground the critique, providing a cultural referent.

Laibach have always embodied elements which manifest the inconsistent mixture which is their aesthetic. The fanaticism that Laibach has presented in performance has always been regarded as suspect by whichever group was represented or connoted through the cultural referent. In the early manifestations of Laibach as a supreme totalitarian organism, the entire organization of Laibach and NSK was regarded suspiciously, especially by the state, which incriminated itself in its criticism of Laibach. By categorizing Laibach’s behavior and rhetoric as dangerous and a threat, the state was defining its own behavior and rhetoric as dangerous and a threat. More recently, the shift towards religious themes has met with disapproval from the church and its representatives in Slovenia.

In staging acts of violence and in constructing a new state, (the virtual state of NSK), Laibach draw attention to these contradictions. The performances of Laibach and overall existence of the state of NSK can be seen as a complete rejection of the artistic strategies of irony, cynical distance and disengagement from actual political circumstances, in favor of an overidentification with the trappings of power and force. Laibach’s attitude is to take ideology more seriously than it is prepared to be taken by its subjects. In so doing, Laibach draw attention to the negative implications of any ideology when pushed to its logical conclusions. The songs confront the listener with the ugly underbelly of state force such as in “Smrt za Smrt,” (“Death for Death”).

SMRT ZA SMRT – DEATH FOR DEATH

nailing criminals

alive to trees

cruelly torturing

gouging out eyes

cutting off ears and tongues

crushing their limbs

piercing biceps

their bound hands

thread through their open wounds

all criminal families killed

some specialists

for executing quilty women

and children

with pocket knives

death for death

death for death

death for death

death

The political arena of the Balkans has changed since this song was written in the early 1980s, but the primary issues regarding the nature of power remain the same. The images of “Death for Death” have a disturbing similarity to reports coming out of Kosovo, although they speak to an earlier period of war and death.

Laibach critique the method through which national symbols and rhetoric are used to demonize an “Other” and legitimize violence in the name of honor, unity and brotherly love. The similarities of Slobodan Milosovich’s tactics to Laibach’s aesthetic are unsettling. Rather than serving as an indictment of the danger in Laibach’s imagery and messages, it should be a wake up call and confirmation of the important message still contained with Laibach’s work. As they have explained before, “LAIBACH in itself is not a danger; the true danger resides in people, it is implanted in human beings like the age-old fear of punishment, and from it the earthly seed of evil stems. Our evil is its projection, so we are a danger to those who in themselves are dangerous,” (from online interviews). jazznblues.club

The distinction to be made is that Laibach manipulate symbols and rhetoric to destabilize rather than fortify subject positions and the power of ruling apparatuses through the exposure of their inconsistencies and pluralities. Laibach’s invocation of force, violence and the aestheticization of power can be read in terms of encouraging reflection by inciting feeling of fear and aggression that lack an enemy against which to vent those feelings. This is quite distinct from the nationalist rhetoric which blatantly portrays a scapegoat and enemy as the hindering factor to a nation’s success, wholeness and unity.

In the film Predictions of Fire, (1995), Slavoj Žižek explains the more effective potential of Laibach’s performance. Rather than providing any answer as to where they stand, Laibach function as a question mark, forcing the individual concerned about Laibach’s messages or the potential danger of misunderstanding or misinterpreting them to answer his or her own question: “What is at stake in their act is precisely to return this question back to ourselves, to ask ourselves. We have there a certain performance. How do we stand towards them? They are not the answer, they are the question. They are a big question mark on stage. We must answer it.”

Laibach has stated that “[o]ur mission at this moment is to make your Evil lose its nerves,” (NSK, 54). It is through the radical exposure of the inconsistencies of ideologies and nationalism that Laibach encourage a reworking of the “floating signifiers” that circulate within both the political and aesthetic arenas. Rather than representing a tragic, static social condition that has outlived itself, Laibach provide a glimpse at a means to effect change. It is this contingency that suggests potential social change. By functioning as a question to the audience, Laibach are challenging us to recognize the opportunities, reject cynicism and engage with what is out there.