Krzysztof Wodiczko at the Polish Pavillion in Venice (Review Essay)

“At the sound of breaking glass, Madame Bovary turned her head and glimpsed outside, close to the panes, peasant faces gazing in.” (G. Flaubert, Madame Bovary)

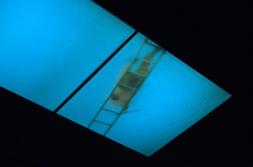

Absorbed by the party at the Marquis d’Andervilliers’s, Emma Bovary views this invasion by a number of uninvited guests as a little more than a tactless intrusion. At some point in Krzysztof Wodiczko’s projection at this year’s Venice Biennale we have to deal with a similar disturbance of the narcissistic adventure of looking. This happens in a sequence of images depicting migrant workers who are washing windows, with one of them pressing his face several times against the glass as he tries, in vain, to peek inside. The protagonists of Wodiczko’s projection are immigrants, people who, removed from their homeland, remain “eternal guests.” We watch them talking to each other in person or on their cell phones, in episodic street scenes as they wait for work to begin or as they wash or repair windows. The silhouettes of these workers become visible to us at various heights. Some are standing outside the windows and on eye level with the viewer, others are positioned above our heads, working on ladders or a hydraulic ramp, or they are suspended by ropes. The projected images are slightly blurry, which reduces the legibility both of the figures and the scenes taking place behind the opaque windows. Wodiczko uses this blur to play on the ambiguity inherent in the immigrants’ social status. While they seem to be always “within reach” they yet remain “on the other side,” behind the view-obstructing windows.. However, the process also works in reverse. As one scene involving a worker trying to peek inside the pavilion from the outside suggests, it is not only we, the visitors, who experience difficulties as we try to see through the blurry windows. The shadowy figures on the other side have trouble seeing us, too.

Absorbed by the party at the Marquis d’Andervilliers’s, Emma Bovary views this invasion by a number of uninvited guests as a little more than a tactless intrusion. At some point in Krzysztof Wodiczko’s projection at this year’s Venice Biennale we have to deal with a similar disturbance of the narcissistic adventure of looking. This happens in a sequence of images depicting migrant workers who are washing windows, with one of them pressing his face several times against the glass as he tries, in vain, to peek inside. The protagonists of Wodiczko’s projection are immigrants, people who, removed from their homeland, remain “eternal guests.” We watch them talking to each other in person or on their cell phones, in episodic street scenes as they wait for work to begin or as they wash or repair windows. The silhouettes of these workers become visible to us at various heights. Some are standing outside the windows and on eye level with the viewer, others are positioned above our heads, working on ladders or a hydraulic ramp, or they are suspended by ropes. The projected images are slightly blurry, which reduces the legibility both of the figures and the scenes taking place behind the opaque windows. Wodiczko uses this blur to play on the ambiguity inherent in the immigrants’ social status. While they seem to be always “within reach” they yet remain “on the other side,” behind the view-obstructing windows.. However, the process also works in reverse. As one scene involving a worker trying to peek inside the pavilion from the outside suggests, it is not only we, the visitors, who experience difficulties as we try to see through the blurry windows. The shadowy figures on the other side have trouble seeing us, too.

The projection involves eight windows and an elongated skylight that offer a glimpse of what goes on outside, behind the windows that separate us from the events taking place on the other side of the opaque glass. The scene automatically makes us think of Alberti’s comparison of paintings to windows. However, even more fitting than this metaphor may be John Berger’s remark that an image is “not so much a framed window open on to the world as a safe let into the wall, a safe in which the visible has been deposited.”(John Berger, Ways of Seeing (London: Penguin, 1990), 103.) Wodiczko’s projection is more about the visibility of the invisible, and even more about seeing and, perforce, non-seeing. What is at stake here is, on the one hand, our seeing the blurry shadows of the immigrants behind the windows and, on the other hand, their inability to see us, the spectators.

The projection involves eight windows and an elongated skylight that offer a glimpse of what goes on outside, behind the windows that separate us from the events taking place on the other side of the opaque glass. The scene automatically makes us think of Alberti’s comparison of paintings to windows. However, even more fitting than this metaphor may be John Berger’s remark that an image is “not so much a framed window open on to the world as a safe let into the wall, a safe in which the visible has been deposited.”(John Berger, Ways of Seeing (London: Penguin, 1990), 103.) Wodiczko’s projection is more about the visibility of the invisible, and even more about seeing and, perforce, non-seeing. What is at stake here is, on the one hand, our seeing the blurry shadows of the immigrants behind the windows and, on the other hand, their inability to see us, the spectators.

Another ambiguity in the projection is the figure of the guest. The word “guests” is written on both sides of the windows. A guest is someone who evokes ambivalent feelings, curiosity and suspicion. The Greek word xenos means a stranger, a foreigner, or guest, but it also refers to a host. In Kant’s project of ewiger Frieden (perpetual peace), hospitality is the right of a stranger.(Immanuel Kant, “Perpetual Peace. A Philosophical Essay,” in Kant’s Principles of Politics, including his essay on Perpetual Peace. A Contribution to Political Science, trans. W. Hastie (Edinburgh: Clark, 1891).) “Making the strange familiar” was the fundamental goal of Wodiczko’s Xenological Instruments, from Alien Staff (1992), through Mouthpiece (Porte-Parole) (1993) to AEgis (1998) and Dis-armor (1999). Alien Staff doubled the immigrant user’s presence (live and on the display of a small monitor) and was meant to be a dialogic device. This philosophy of dialogue was taken further in Mouthpiece which equipped its wearer with a communication gadget that allowed him or her to speak “through somebody else’s mouth.” An immigrant himself, Wodiczko followed Julia Kristeva by explaining these instruments through the “metaphor of inner strangeness, being in-between.”(“Chcia?bym si? na co? przyda? . . .”, Krzysztof Wodiczko talks to Hanna Wróblewska, in Krzysztof Wodiczko. Pomnikoterapia, exh. cat. Zach?ta Narodowa Galeria Sztuki (Warsaw, 2005), 71.) By way of the Freudian uncanny, strangeness connects what is ours – the familiar, intimate, or native – with what is suspicious, strange, or disturbing.(See Julia Kristeva, Étrangers à nous-mêmes (Paris: Fayard, 1988), 252. English edition: Strangers to Ourselves, trans. Leon S. Roudiez (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994), 182.)

In Guests strangeness manifests itself in terms of how we construe Otherness. An earlier projection by Wodiczko entitled If You See Something… (2005) at Galerie Lelong in New York was set in the context of the policies of the Bush administration and referenced the reproduction of strangeness through relationships of fear and suspicion. Here immigrants behind milk-glass windows spoke about their harassment and the draconian laws enforced in the name of the war on terror.

In Guests strangeness manifests itself in terms of how we construe Otherness. An earlier projection by Wodiczko entitled If You See Something… (2005) at Galerie Lelong in New York was set in the context of the policies of the Bush administration and referenced the reproduction of strangeness through relationships of fear and suspicion. Here immigrants behind milk-glass windows spoke about their harassment and the draconian laws enforced in the name of the war on terror.

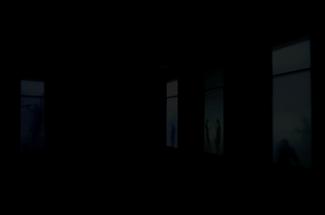

Both in If You See Something… and in Guests we are dealing with sometimes very personal narratives and with the personalization of “immigrant status” through the physical presence of the individuals on the other side of the glass. In the New York piece, which consisted of projected images on four narrow vertical windows that contrasted with the darkened interior in the gallery, the immigrant figures appeared to be even more “on the other side” – in a space of psychosocial alienation – than in the Biennale piece. In Venice, the wide windows (the projection screens) on three walls and the ceiling create a stronger impression of an opening, a blurring of the line that separates the inside from the outside.

Both in If You See Something… and in Guests we are dealing with sometimes very personal narratives and with the personalization of “immigrant status” through the physical presence of the individuals on the other side of the glass. In the New York piece, which consisted of projected images on four narrow vertical windows that contrasted with the darkened interior in the gallery, the immigrant figures appeared to be even more “on the other side” – in a space of psychosocial alienation – than in the Biennale piece. In Venice, the wide windows (the projection screens) on three walls and the ceiling create a stronger impression of an opening, a blurring of the line that separates the inside from the outside.

This is due chiefly to the polyphonic structure of the installation and the way in which Guests immerses the viewer in a series of events that take place alternately or in several windows at once. The images of immigrants that emerge from the projection are devoid of any stigmatization. We watch different types of workers as they go about their duties: a Lebanese intellectual, a Vietnamese poet, and a group of foreign students. Apart from scenes involving the immigrants’ difficult and sometimes even hopeless situations (for instance, a Chechen refugee living in limbo for years, waiting in vain to be granted refugee status) we see dancing Vietnamese women and the xenophobic behavior of Polish and Italian street youths. Or we overhear a conversation of women who work for organizations providing legal and social aid to immigrants. To gather all this material Wodiczko spent many hours talking with immigrants in Rome and Warsaw.

The current tensions surrounding immigration issues, the restrictive regulations being introduced by EU member states in an attempt to seal their borders, the dramatic situation of illegal immigrants caused by the global economic crisis and the rise of anti-immigrant sentiment—all these things contributed to Wodiczko ’s interest in the experience of European migrants. In the end, the Polish pavilion was transformed into a place that produces insights into Europe’s relationship with its foreign guests literally by defying its surroundings, the Giardini gardens with their clear division into national pavilions.

It impossible to perceive the entire projection from a fixed position because the dramaturgy of the scenes and episodes that make up Guests changes constantly. The simultaneity of the projections activates and contextualizes the space between them—a space designed for the viewer who now enters a stage previously reserved for the artist.

It impossible to perceive the entire projection from a fixed position because the dramaturgy of the scenes and episodes that make up Guests changes constantly. The simultaneity of the projections activates and contextualizes the space between them—a space designed for the viewer who now enters a stage previously reserved for the artist.

The darkened space and moving pictures of Wodiczko’s installation are reminiscent of the cinema, a place where a sense of immersion in the image blurs the distinction between viewer and visual representation, and where the spectator experiences herself in the place where the images is located.(See Hans Belting, “Towards an Anthropology of the Image,” in Anthropologies of Art, ed. Mariet Westermann (Clark Art, Institute and Yale University Press, 2005).) However, the mechanisms of identification that are so characteristic of film are resisted by Wodiczko; despite the viewer’s immersion in the illusory world of the video, the figures behind the windows remain poorly visible, often beyond recognition. Despite their natural size and close proximity to the viewer, they are separated from the onlooker by an insurmountable obstacle. This play with visibility and invisibility that persistently prevents the viewer from identifying with the images they see was already present in earlier projects. In Hiroshima (1999), for example, testimonies by victims of the atomic bomb were accompanied by close-up images of hands that were either at rest or gesticulating just above the surface of the Ota river at the foot of the ruins of the Atomic Bomb Dome. As Rosalyn Deutsche commented, “[t]he projection also helped the human victims speak by highlighting the supplemental language of their gesturing hands while withdrawing their faces, a withdrawal that may have been prompted by practical considerations but that also protected the speakers from the grasp of vision with image, vision that knows too much and so betrays the speaker.”(Rosalyn Deutsche, “The Art of Witness: Krzysztof Wodiczko’s Hiroshima Projection,” published in Polish as “Sztuka ?wiadectwa: Projekcja w Hiroszimie Krzysztofa Wodiczki,” trans. Dorota Kozi?ska, in Krzysztof Wodiczko. Pomnikoterapia, 20.)

Another kind of protection was used in Wodiczko`s most recent work, involving veteran soldiers interviewed by the artist. In Veterans` Flame (2009) the artist completely abstained from any visual representation of the protagonists. Here the veterans’ testimonies are accompanied by an image of a lit candle that moves in sync with their recorded voices.(Veterans` Flame is now presented in Fort Jay on the Governors Island within PLOT 09.) The artist employed a reverse procedure in the Pozna? Projection (2008) where blown-up images of homeless people’s heads emerged high above the viewers’ heads inside the city hall’s clock tower. This time (despite an excess of visibility) the overlapping voices of the speakers made it impossible to understand what they were saying, preventing not only empathy but also any narrative framing of their experiences.

In Guests, filmic illusion has little to do with fiction. The footage is based on documentary recordings, the scenes are played by amateur extras or by the immigrants themselves, and some of the dialogues and monologues are recordings of the artist’s discussions with the immigrants. This combination of documentary footage with staged material raises questions concerning the relationship between the documented and the recreated. It also touches on the dialectic of the genre of documentary itself, with its mixing of live recording and fiction. Moreover, the artist’s use of the documentary provokes questions regarding the ethical dimension of aesthetic decisions and, more broadly speaking, an artistic approach in which the author himself is the least desirable figure.

Much has been written about the crucial role of ethics in Wodiczko’s practice, especially a Lévinas-style “ethics of the primacy of otherness over selfness.”(See more: Rosalyn Deutsche, “Sztuka ?wiadectwa: Projekcja w Hiroszimie Krzysztofa Wodiczki,” Andrzej Turowski, “Przemieszczenia i obrazy dialektyczne Krzysztofa Wodiczki,” in Krzysztof Wodiczko. Pomnikoterapia.) Wodiczko’s series of Instruments for self-presentation and communication can be linked to this kind of ethics.

Another instrument that enabled outsiders to appear in the public sphere were outdoor projections such as Town Hall Tower Projection in Cracow (1996) whose video projectors and loudspeakers enabled those on the margins to talk about their experiences in public.

In Wodiczko’s subsequent installations the voices were always those of outsiders who explicitly agreed to be taped, as in the War Veteran Projection in Denver (2008). This installation was preceded by seven months of meetings and discussions with homeless veterans who recorded, then transcribed and co-edited their own testimonies. In Tijuana Projection (2001) these pre-recorded testimonies were modified in real time by the projection’s women protagonists who commented on their own pre-recorded statements with the help of a special device.

In Denver, Wodiczko designed a vehicle that fired sounds and images for homeless veterans. The artist removed the missile launch platform from the back of a military Humvee and replaced it with a specially designed projection device that became a medium through which veterans could speak up.

Wodiczkos’s Instruments imply a kind of contemporary homo sacer. As Piotr Piotrowski writes, “Wodiczko . . . tried to reverse the process of alienation by reinvesting immigrants with their identity, their histories, emotions . . . giving them a language. . . . But it is not only a matter of language; also of reinvesting the immigrant with his or her human status, so that they are not perceived in terms of ‘bare life.’”(Piotr Piotrowski, “Biopolityka i demokracja,” in Krzysztof Wodiczko. Doktor honoris causa Akademii Sztuk Pi?knych w Poznaniu (Pozna?: Akademia Sztuk Pi?knych w Poznaniu, 2007), 18.) We can detect Wodiczko’s homo sacer in the blurry figures behind the windows in the Venice pavilion, indistinct silhouettes and moving shadows on the verge of invisibility.

Wodiczkos’s Instruments imply a kind of contemporary homo sacer. As Piotr Piotrowski writes, “Wodiczko . . . tried to reverse the process of alienation by reinvesting immigrants with their identity, their histories, emotions . . . giving them a language. . . . But it is not only a matter of language; also of reinvesting the immigrant with his or her human status, so that they are not perceived in terms of ‘bare life.’”(Piotr Piotrowski, “Biopolityka i demokracja,” in Krzysztof Wodiczko. Doktor honoris causa Akademii Sztuk Pi?knych w Poznaniu (Pozna?: Akademia Sztuk Pi?knych w Poznaniu, 2007), 18.) We can detect Wodiczko’s homo sacer in the blurry figures behind the windows in the Venice pavilion, indistinct silhouettes and moving shadows on the verge of invisibility.

The figure of the refugee, which is so hard to define politically, as Giogio Agamben writes, highlights a crisis of the modern fiction of sovereignty. “Bringing to light the difference between birth and nation, the refugee causes the secret presupposition of the political domain—bare life— to appear for an instant within that domain.”(Giorgio Agamben, Homo Sacer. Sovereign Power and Bare Life, trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen, (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 1998), p. 131.)

Those whose testimonies Wodiczko used were mostly people from outside Europe, or at least from outside of the European Union (with the exception of Romania, which, however, is not a member of the Schengen zone). Several scenes include a group of about ten workers from Vietnam whose journey to the shooting location required special preparations because they preferred to avoid public transportation for fear of deportation.(Poland is the third preferred destination for the Vietnamese in Europe, after France and Germany, and they are the largest ethnic minority in Poland. Their population is estimated at 40.000 to 60.000, but the exact figure remains unknown because most cross the border into Poland illegally and work in the shadow economy. Restrictive visa and asylum policies make it virtually impossible for them to legalize their stay. Lacking legal papers, they are unable to leave Poland and, despite their large number, remain uncountable and as it were invisible.)

Those whose testimonies Wodiczko used were mostly people from outside Europe, or at least from outside of the European Union (with the exception of Romania, which, however, is not a member of the Schengen zone). Several scenes include a group of about ten workers from Vietnam whose journey to the shooting location required special preparations because they preferred to avoid public transportation for fear of deportation.(Poland is the third preferred destination for the Vietnamese in Europe, after France and Germany, and they are the largest ethnic minority in Poland. Their population is estimated at 40.000 to 60.000, but the exact figure remains unknown because most cross the border into Poland illegally and work in the shadow economy. Restrictive visa and asylum policies make it virtually impossible for them to legalize their stay. Lacking legal papers, they are unable to leave Poland and, despite their large number, remain uncountable and as it were invisible.)

The invisibility of stateless persons was the subject of a projection shown by Wodiczko four years earlier in Basel. Here the public saw only the legs of the sans papiers dangling from the roof of the Kunstmuseum and heard overlapping fragments of dialogues and songs sung in the migrants’ native languages. The projection, entitled Sans-Papiers, highlighted the curious non-existence of people without papers or faces, stripped of their right to be visible.

The question of papers and documents, including work and residence permits, runs through many of Wodizko’s projections. The glass containers of Alien Staff were filled with passport photos, visa applications, as well as official letters of refusal and approval. In a rarely cited work from 1987,(Work presented in the exhibition Immigrants and Refugees/ Heroes or Villains, Exit Art, New York, 1987.) the figure of an immigrant cleaning person, projected on a column inside New York’s Exit Art gallery, bends forward to pick up his green card which, intensely illuminated, appears to him like an elusive mirage. As Zygmunt Bauman writes, “passports, visas, customs and immigrations controls were among the major inventions of the art of modern government.”(Zygmunt Bauman, Society Under Siege (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2002), 108.)

The question of papers and documents, including work and residence permits, runs through many of Wodizko’s projections. The glass containers of Alien Staff were filled with passport photos, visa applications, as well as official letters of refusal and approval. In a rarely cited work from 1987,(Work presented in the exhibition Immigrants and Refugees/ Heroes or Villains, Exit Art, New York, 1987.) the figure of an immigrant cleaning person, projected on a column inside New York’s Exit Art gallery, bends forward to pick up his green card which, intensely illuminated, appears to him like an elusive mirage. As Zygmunt Bauman writes, “passports, visas, customs and immigrations controls were among the major inventions of the art of modern government.”(Zygmunt Bauman, Society Under Siege (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2002), 108.)

In Guests, a recurring theme in the workers’ conversations is their inability to get a job. The emergence of the “European citizen” as a new historical figure has been accompanied, according to Etienne Balibar, by a “violent process of exclusion whose main instrument (not the only one) is the quasi-military enforcement of ‘security borders,’ which recreates the figure of the stranger as political enemy.”(Étienne Balibar, “Europe as Borderland,” The Alexander von Humboldt Lecture in Human Geography, University of Nijmegen, November 10, 2004, http://socgeo.ruhosting.nl/colloquium/Europe%20as%20Borderland.pdf (accessed April 15, 2009).) In the recorded conversations in Guests we can certainly hear echoes of of hostility towards ethnic or linguistic “strangeness.”

In Guests, a recurring theme in the workers’ conversations is their inability to get a job. The emergence of the “European citizen” as a new historical figure has been accompanied, according to Etienne Balibar, by a “violent process of exclusion whose main instrument (not the only one) is the quasi-military enforcement of ‘security borders,’ which recreates the figure of the stranger as political enemy.”(Étienne Balibar, “Europe as Borderland,” The Alexander von Humboldt Lecture in Human Geography, University of Nijmegen, November 10, 2004, http://socgeo.ruhosting.nl/colloquium/Europe%20as%20Borderland.pdf (accessed April 15, 2009).) In the recorded conversations in Guests we can certainly hear echoes of of hostility towards ethnic or linguistic “strangeness.”

Behind the windows of Wodiczko’s Venice projection immigrants talk of deportations; of living in refugee camps; of short-term extensions for temporary residence permits; of the fear of deportation; of Dublin Convention detentions (forcing them to stay in the country where they first applied for refugee status) and of their constant experience of social exclusion. However, it is not the immigrants themselves who are the challenge here but the invisible borders that separate them from everyone else. More than anything the immigrants are a challenge to hospitality. According to Jacques Derrida hospitality is an experience of risk and the necessity to deconstruct our sense of being at home.(Jacques Derrida, Of Hospitality (Cultural Memory in the Present), trans. Anne Dufourmantelle, Rachel Bowlby (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2000).) The real border, as Wodiczko argued in the spirit of Julia Kristeva, lies between the foreigner and our fear of being strange or foreign ourselves.(See Krzysztof Wodiczko, “Designing for the City of Strangers,” in The Design, Culture, Reader (London and New York: Routledge, 2009), 264.) In Kristeva’s “confederation of otherness” there are echoes of Kant’s cosmopolitan vision, a global civic community full of hospitality. Instead of such idealism, Wodiczko proposes a transition from the stranger as enemy to the stranger as citizen.(Balibar, “Strangers as Enemies . . . ,” 13.)

As an installation Guests is convincing and seductive. Yet the dreamy spectacle becomes a kind of trap as you pick up the headphones and start to listen to the voices and conversations from behind of the windows. The duality of this experience – audio and visual – prevents the work from becoming didactic. It is a space full of ambivalence, a space of separation but also a space to be shared with others. And yet Guests isnot only about migrants moving to Europe, it also forces us to think about what it means to be European.

As an installation Guests is convincing and seductive. Yet the dreamy spectacle becomes a kind of trap as you pick up the headphones and start to listen to the voices and conversations from behind of the windows. The duality of this experience – audio and visual – prevents the work from becoming didactic. It is a space full of ambivalence, a space of separation but also a space to be shared with others. And yet Guests isnot only about migrants moving to Europe, it also forces us to think about what it means to be European.

A different version of this text was published in Krzysztof Wodiczko. Guests, ed. Bożena Czubak, exhib cat., Zach?ta National Gallery of Art, Warsaw; Charta Books LTD, New York City, Warsaw, 2009.

A different version of this text was published in Krzysztof Wodiczko. Guests, ed. Bożena Czubak, exhib cat., Zach?ta National Gallery of Art, Warsaw; Charta Books LTD, New York City, Warsaw, 2009.

Translated by Marcin Wawrzy?czak.