Jan Švankmajer: The Complete Short Films 1964-1992 (DVD Review)

Jan Švankmajer: The Complete Short Films 1964-1992, Released on DVD by the BFI DVD Publishing, 2007. 313 min, 1.33:1 Aspect Ratio.

At 74, Jan Švankmajer continues to stun and startle. Recently, he has been awarded the Crystal Globe at the 44th International Film Festival in Karlovy Vary for Outstanding Artistic Contribution to World Cinema. He reacted to this prestigious Czech prize with a somewhat ironic attitude, explaining once more to the audience and the academy — after more than forty years of a career based on relentless anti-nationalism — that he does not consider his films as a property of the nation, only of himself.

His last work, P?ežít sv?j život (teorie a praxe) (Surviving Life (Theory and Practice)), to be released in 2010, will be a horror comedy about an aging man who is trying to escape from his life’s frustrations by recalling images from his childhood and ends up as a bigamist.

His last work, P?ežít sv?j život (teorie a praxe) (Surviving Life (Theory and Practice)), to be released in 2010, will be a horror comedy about an aging man who is trying to escape from his life’s frustrations by recalling images from his childhood and ends up as a bigamist.

Having been a fan of Švankmajer since my early days (Argentinean TV in the 80´s was cool enough to show his work), I had trouble remaining soberly objective when I recently got my hands on the British DVD edition of Švankmajer’s films. This three-DVD set with a complete collection of his shorts was published by the BFI in 2007 for Region 2. Compared to the Kino Video release for the US and Canada, the BFI set has more films, better transfers, and contains a whole disc of rare extras and a 56-page book. As Švankmajer is a declared surrealist, I feared that the BFI set would have a weird, byzantine menu designed by Švankmajer-wannabes. Luckily, it features a sample background music from one of the shorts, with the possibility of programming your own Švankmajer session by themes, based either on the ideological content or some common element – simple, effective and helpful as the last possible gesture of kindness from the director to the audience. Like in the beginning of a rollercoaster ride, you say to yourself “from now on, you are on your own.” Even with English subtitles.

Having been a fan of Švankmajer since my early days (Argentinean TV in the 80´s was cool enough to show his work), I had trouble remaining soberly objective when I recently got my hands on the British DVD edition of Švankmajer’s films. This three-DVD set with a complete collection of his shorts was published by the BFI in 2007 for Region 2. Compared to the Kino Video release for the US and Canada, the BFI set has more films, better transfers, and contains a whole disc of rare extras and a 56-page book. As Švankmajer is a declared surrealist, I feared that the BFI set would have a weird, byzantine menu designed by Švankmajer-wannabes. Luckily, it features a sample background music from one of the shorts, with the possibility of programming your own Švankmajer session by themes, based either on the ideological content or some common element – simple, effective and helpful as the last possible gesture of kindness from the director to the audience. Like in the beginning of a rollercoaster ride, you say to yourself “from now on, you are on your own.” Even with English subtitles.

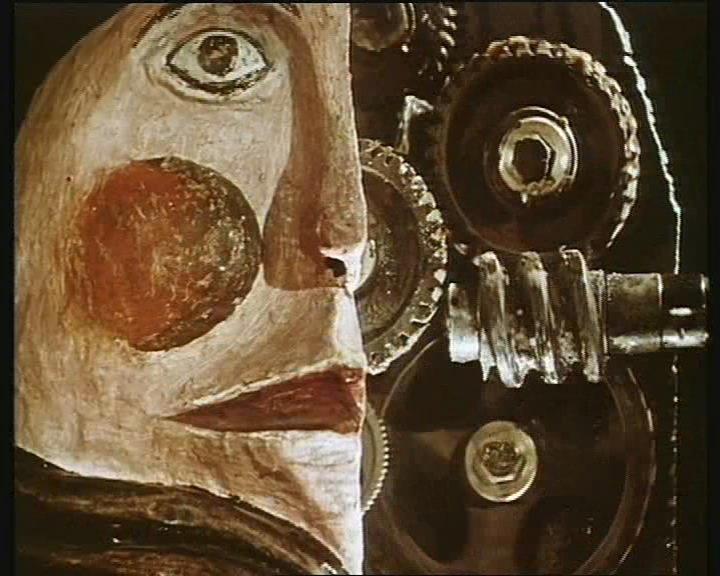

Trying to emulate a first viewer, I will concentrate on some details. Švankmajer’s shorts are rarely animated using just one specific technique – stop motion, pixilation, or drawings – rather, he prefers to combine elements of all three styles. His signature technique, however, is montage. Sometimes, it is a montage of incredible speed, giving the films a psychotic and violent feel. Most films are synchronized with a crudely rhythmic music (Punch and Judy). An extreme example of synchronicity between image and sound is A Game With Stones, where xylophone music matches the violent series of dancing stones. Some people may well find this effect annoying. It is interesting that the director also credits himself as the scriptwriter, because imagining such a film as words on paper is almost impossible.

Trying to emulate a first viewer, I will concentrate on some details. Švankmajer’s shorts are rarely animated using just one specific technique – stop motion, pixilation, or drawings – rather, he prefers to combine elements of all three styles. His signature technique, however, is montage. Sometimes, it is a montage of incredible speed, giving the films a psychotic and violent feel. Most films are synchronized with a crudely rhythmic music (Punch and Judy). An extreme example of synchronicity between image and sound is A Game With Stones, where xylophone music matches the violent series of dancing stones. Some people may well find this effect annoying. It is interesting that the director also credits himself as the scriptwriter, because imagining such a film as words on paper is almost impossible.

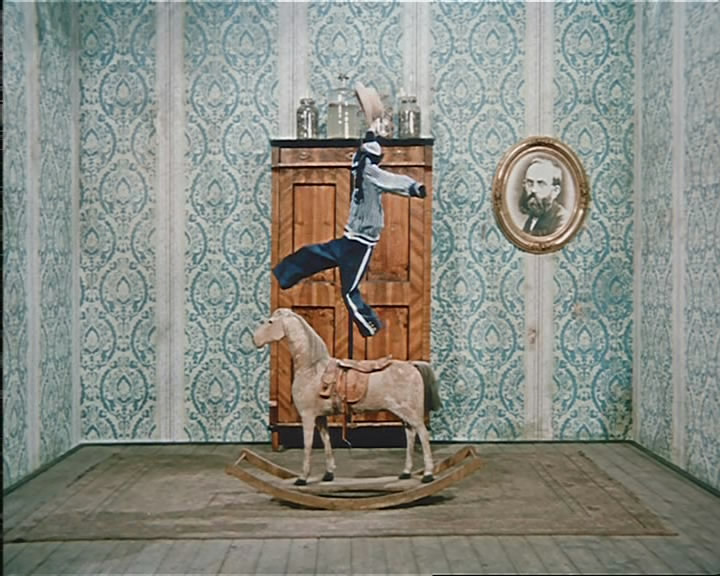

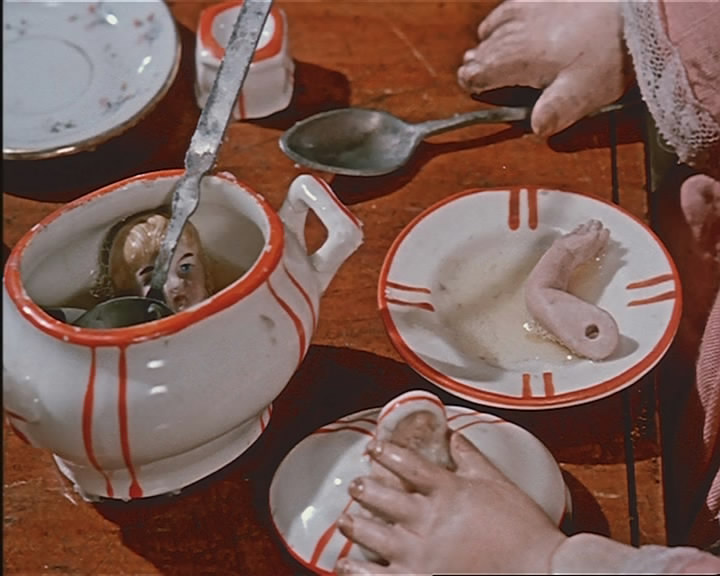

To Švankmajer, we are nothing but flesh and dust. His films are about the eternal contradictions of the human condition, where we as the audience witness of how nature opposes cultural structures. Man´s quest for virtue and social well-being tends to contradict his natural instincts. We realize that every short is a story which already happened an unconceivable numbers of times before we press play on the DVD, when the characters start to act in an automatized fashion. If there are representations of human emotions in the films –and the author wants us to recognize them as representations – they amount to static poses. Nature and culture are two forces that shape the characters’ behavior and emerging situations. The eternal battle of the two elements turns into a hypnotic mantra because of the traumatic repetitions in the story. Švankmajer appeals to our sensibility, testing our tolerance, as he chooses symbols that evoke the simplicity of childhood and the grimness of death. Trivializing death, Švankmajer exposes the fakeness and shallowness of the modern world. Everything will decay, no matter what, and nature will prevail over culture’s shallowness. Even celebrated cultural events, such as sports are unmasked in Virile Games, where individual psyche merges with a human mass, and pieces of flesh transit into an eventual collision. Those are Švankmajer´s visual arguments.

To Švankmajer, we are nothing but flesh and dust. His films are about the eternal contradictions of the human condition, where we as the audience witness of how nature opposes cultural structures. Man´s quest for virtue and social well-being tends to contradict his natural instincts. We realize that every short is a story which already happened an unconceivable numbers of times before we press play on the DVD, when the characters start to act in an automatized fashion. If there are representations of human emotions in the films –and the author wants us to recognize them as representations – they amount to static poses. Nature and culture are two forces that shape the characters’ behavior and emerging situations. The eternal battle of the two elements turns into a hypnotic mantra because of the traumatic repetitions in the story. Švankmajer appeals to our sensibility, testing our tolerance, as he chooses symbols that evoke the simplicity of childhood and the grimness of death. Trivializing death, Švankmajer exposes the fakeness and shallowness of the modern world. Everything will decay, no matter what, and nature will prevail over culture’s shallowness. Even celebrated cultural events, such as sports are unmasked in Virile Games, where individual psyche merges with a human mass, and pieces of flesh transit into an eventual collision. Those are Švankmajer´s visual arguments.

Creating a unique emotional void, the director makes use of objects that impersonate our actions and roles. He is not just moving the objects, he is exploring their inner life; by getting deep within the object, he sucks out from it every possibility of expression. A potato can be a fantasy image of our powerless childhood. If not, he will use a living actor, meticulously and systematically depersonalizing his object of interest. Human matter will be ready to accomplish an assignment to become another being/thing.

Creating a unique emotional void, the director makes use of objects that impersonate our actions and roles. He is not just moving the objects, he is exploring their inner life; by getting deep within the object, he sucks out from it every possibility of expression. A potato can be a fantasy image of our powerless childhood. If not, he will use a living actor, meticulously and systematically depersonalizing his object of interest. Human matter will be ready to accomplish an assignment to become another being/thing.

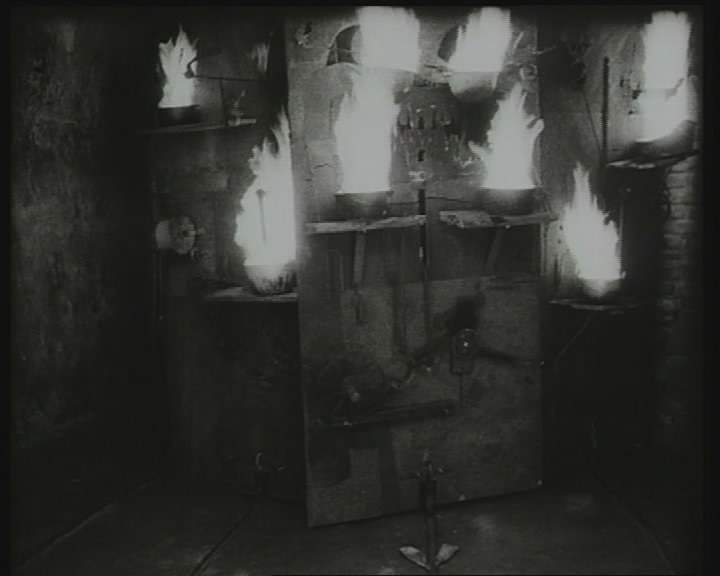

The feeling of excess comes to mind, when we get to see everyday objects or so-called “common people” exceeding their limits and breaking their structures into complete anarchy. Now Švankmajer looks into the concept of anarchy, where everything is nameless, and objects are used for unthinkable purposes. By mixing the incompatible to the point of disgust, he demonstrates that by our cultural statements, we create roles for the organic and inorganic elements, integrating them into the pre-existing schemata of our lives. We mix flour and water to create the idea of bread, but bread is not really there. Culture is but a thin veil over the imperceptible chaos surrounding us.

The feeling of excess comes to mind, when we get to see everyday objects or so-called “common people” exceeding their limits and breaking their structures into complete anarchy. Now Švankmajer looks into the concept of anarchy, where everything is nameless, and objects are used for unthinkable purposes. By mixing the incompatible to the point of disgust, he demonstrates that by our cultural statements, we create roles for the organic and inorganic elements, integrating them into the pre-existing schemata of our lives. We mix flour and water to create the idea of bread, but bread is not really there. Culture is but a thin veil over the imperceptible chaos surrounding us.

Švankmajer’s message may appear pessimistic for the first-time viewers, but it is thoroughly refreshing for those initiated to his art. One can see that his movies must have suffered years of censorship: these pieces of art are conscious of their political persecution. They might be seen as an attitude of resistance and a life lived.

The outstanding extra feature that is relevant to the DVD collection atmosphere is the documentary The Cabinet of Jan Švankmajer (1984), made by a team of British animators, the Quay Brothers. They were clever enough to transform the artist’s uncooperative interview into a distanced portrait, deeply symbolic and yet abstract.