Jan Tichy: Light Source

Jan Tichy (Czech, b. 1974) is a Chicago-based artist who works at the intersection of multiple media. Central to his practice is the use of video projection as a time-based source of light as well as modernist photographic histories that serve as both formal inspiration and conceptual lens for exploring contemporary sites. His recent project 1979:1-2012:21: Jan Tichy Works with the MoCP Collection was on view at the Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, October 12- December 23, 2012 (http://www.mocp.org/exhibitions).

At the core of Jan Tichy’s multimedia practice is an investigation of the protean and plastic properties of light, an exploration grounded in the history of photography and by extension film and video. For Tichy, light is a medium of infinite possibility and a means for making visible the hidden histories of his chosen sites, whether a traditional gallery, a public housing complex, or a museum collection. Working across media, including sculpture, installation, photography, and video (often combined within individual projectsor pieces), Tichy remaps the physical and conceptual spaces his works occupy.

Born in Prague in 1974, Tichy came of age at the time of the so-called Velvet Revolution and the sweeping political changes that occurred throughout Eastern Europe. He immigrated to Jerusalem in 1993 upon discovering his Jewish identity; here and against the backdrop of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, he studied political science before turning to photography and sculpture. Tichy continued his graduate studies in art at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), where he currently teaches, and has lived in Chicago since 2007.

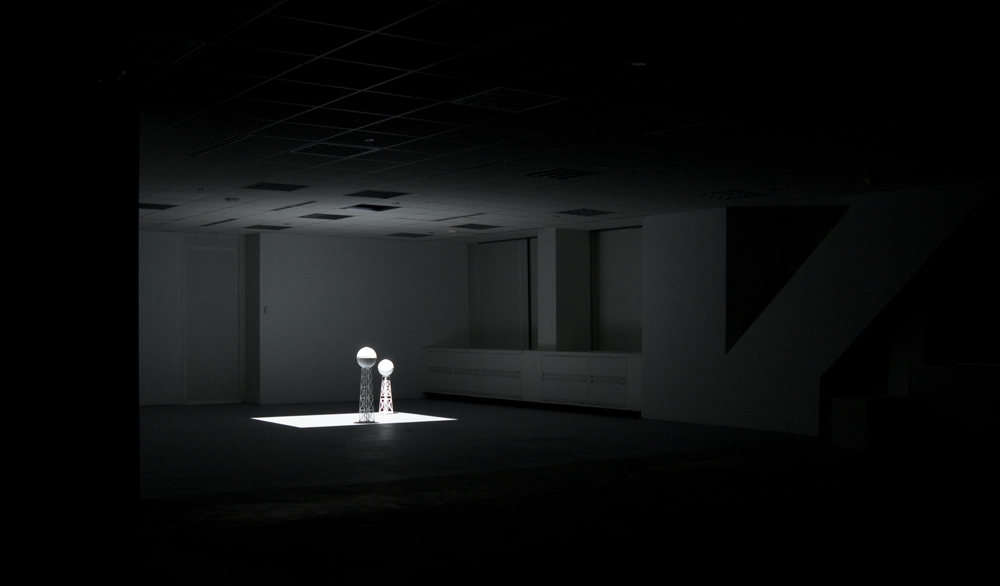

Undoubtedly informed by the political events that have shaped his personal and professional biography, Tichy’s practice includes images of architecture as emblems of political power, as well as publicly sited interventions in the urban landscape. The artist’s formal language draws on the bold geometry of distinct monuments of modernist architecture, including the Czech Cubism of his native Prague, Tel Aviv’s White City, and the skyline of his adopted Chicago. His early installations utilized handcrafted paper replicas of iconic buildings, such as a high-security prison in Israel or the country’s Dimona nuclear facility, based on the Czech tradition of paper modeling. Situated on the floors of darkened spaces, these architectural mis-en-scènes are then activated by projections of light to heighten notions of security and surveillance. Later works incorporate more abstract and universal kinds of structures, such as water towers, stacked grids, and small domes, to create ambiguous topographies that are similarly transformed by shifting contrasts of black and white.

Undoubtedly informed by the political events that have shaped his personal and professional biography, Tichy’s practice includes images of architecture as emblems of political power, as well as publicly sited interventions in the urban landscape. The artist’s formal language draws on the bold geometry of distinct monuments of modernist architecture, including the Czech Cubism of his native Prague, Tel Aviv’s White City, and the skyline of his adopted Chicago. His early installations utilized handcrafted paper replicas of iconic buildings, such as a high-security prison in Israel or the country’s Dimona nuclear facility, based on the Czech tradition of paper modeling. Situated on the floors of darkened spaces, these architectural mis-en-scènes are then activated by projections of light to heighten notions of security and surveillance. Later works incorporate more abstract and universal kinds of structures, such as water towers, stacked grids, and small domes, to create ambiguous topographies that are similarly transformed by shifting contrasts of black and white.

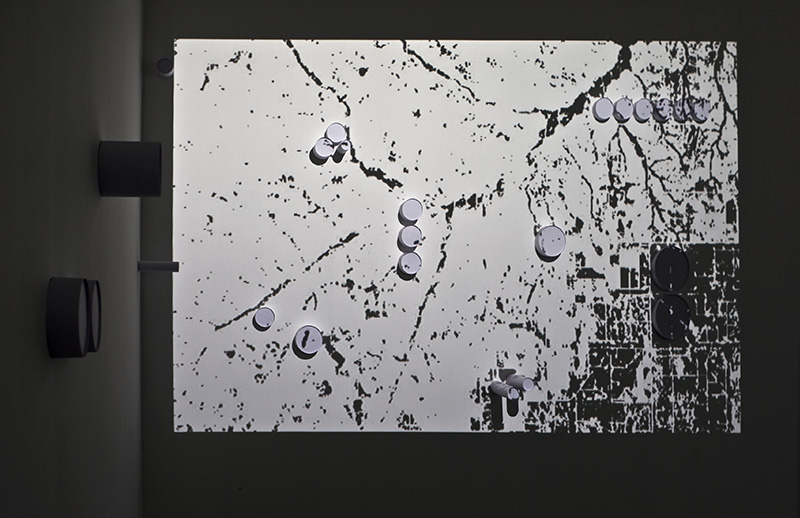

Tichy’s sources of light take the form of lines and spheres set in motion, as well as manipulated images of diagrams and maps, all generated through digital video projections. In Installation No. 5 (Threshold), 2008, three unidentified aerial maps slowly materialize within three white fields projected onto a gallery wall. A series of paper cylinders attached perpendicular to the wall’s surface form an abstract cityscape that is gradually immersed in total darkness when the projected maps eventually fade to black.

In 1839, William Henry Fox Talbot declared his discovery of photogenic drawing “the art of fixing a shadow,” “even if thrown back into the sunbeam from which derived its origin.”William Henry Talbot Fox, “Some Account of the Art of Photogenic Drawing,” in Photography: Essays & Images, ed. Beaumont Newhall (NY: Museum of Modern Art, 1980), p. 25. This art of light and shadow was later termed photography, a history Tichy embraces, including Constructivist montage and Surrealist experiments with solarization. Of particular influence are the works of László Moholy-Nagy, who proclaimed the importance of “the organization of light and shadow effects [in] produc[ing] a new enrichment of vision.”László Moholy-Nagy wrote this statement in a caption for one of his photograms, in 1000 Photo Icons by George Eastman House (Cologne: Taschen, 2003), p. 521. Moholy-Nagy’s “new vision,” embedded in the Bauhaus belief in art’s ability to transform society through the use of modern technologies, called for the integration of art, industry and design. The result was a broad spectrum of works in all media that captured the simultaneity of light, space and time.

<

Things To Come 1936-2012 – Laszlo Moholy Nagy and Jan Tichy (excerpt 1:30 min) from Jan Tichy on Vimeo.

Tichy pays direct homage to Moholy-Nagy in Things to Come 1936–2012 (2012). Three-channel digital video projection. Dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist and Richard Gray Gallery.) This three-channel digital projection animates filmic work by the Hungarian artist, all lost black-and-white sequences originally created for the 1936 science-fiction film Things to Come that never made the final cut. Based on a screenplay by H.G. Wells, the film’s futuristic themes centered on war and technological progress meld with Moholy-Nagy’s kaleidoscopic images of geometrical forms and abstract patterns of light that sought to reimagine a new world order.

Moholy-Nagy came to the United States in 1937 to implement his new vision as director of the New Bauhaus in Chicago, which later became the School of Design, then the Institute of Design. Three years after the artist’s death in 1946, the school became part of the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT). Devoted to art, design and architecture, IIT furthered the ideas of Moholy-Nagy, as well as the Chicago School of Architecture and the classical modernism of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who directed its school of architecture and whose S.R. Crown Hall (1956) remains the centerpiece of the IIT campus.

This quintessential example of Miesian architecture, with its exposed steel structure, open interior and translucent walls of glass, became both the site and subject of Tichy’s Lighting the Crown Hall, (2009), a public project realized under the auspices of SAIC and in collaboration with an international cadre of students. Through a series of interior video projections that occurred on a single night, Crown Hall was transformed into a light box, a transparent frame that conflated notions of interior and exterior, past and present, while bridging the histories of Moholy-Nagy and Mies. The building’s glass panels formed a continuous screen onto which were projected views of Chicago (the elevated train, fragments of architecture, trees, bugs, and birds), alongside abstract images of intersecting lines, pixelated grids, and roving geometrical shapes reminiscent of Moholy-Nagy’s photograms.

Here and in other public works, Tichy employs light as a tool of embodiment, a medium that gives presence to the art historical figures his works draw upon, and empowerment to the non-art publics with whom he collaborates. Much in the same way that Krzysztof Wodiczko’s public projections commemorate those forgotten in the historical narratives of victory, Tichy’s Project Cabrini Green (2011), a public art installation utilizing LED lights, gave voice to the youth community effected by the demolition of Chicago’s Cabrini Green public housing complex. For this multi-tiered project, Tichy (together with Efrat Appel) collaborated with Chicago youth and students at SAIC in a series of workshops to produce poems that expressed their responses to contemporary urban struggles, including violence, displacement, gentrification, and inner-city renewal. Their poems were translated into a series of light patterns, each represented by an individual LED module placed inside 134 of Cabrini’s vacated apartments. The light-poems would blink throughout the month-long demolition until, one by one, they were eventually destroyed as the building complex was razed.

Despite the project’s temporality, these urban youth, assuming a ghostly yet subversive presence, were able to re-inhabit and, thus, repossess Cabrini as a site of complex social relations versus a mere physical entity. Art historian and critic Rosalyn Deutsche centers her discourse on public art on these kinds of political reinventions of public space. In her book Evictions: Art and Spatial Politics, she looks to radical definitions of democracy and urbanism, such as those posed by political philosopher Claude Lefort, who defines true democracy as unstable, and power as “fundamentally indeterminate.” Lefort characterizes public space as “the social space where, in the absence of a foundation, the meaning and unity of the social is negotiated – at once constituted and put at risk.”Claude Lefort quoted in Rosalyn Deutsche, “Agoraphobia,” in Evictions: Art and Spatial Politics (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1996), p. 273.

In his most recent project 1979:1-2012:21: Jan Tichy Works with the MoCP Collection, the artist similarly confronts the stability and authority of institutional power, in this case the permanent collection of Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Photography. Like other contemporary artists working with research-based, archival practices, Tichy engages the MoCP collection not as a static repository of objects and information, but rather “as an active, regulatory discursive system.”Okwui Enwezor, “Archive Fever: Photography between History and the Monument,” in Archive Fever: Uses of the Document in Contemporary Art, exhibition catalog (NY: International Center for Photography, 2008), p. 11. This system includes the creation of new interpretive instruments: primary is an exhibition of select photographs from the collection curated by Tichy, including those chosen by the MoCP’s six curators, as well as new works created by the artist in response to the images on view. A group of local MFA students worked with Tichy in redesigning the museum’s website that serves as a publicly accessible archive of its collection of nearly 11,000 images. Collection highlights include works by important figures from the New Bauhaus/Institute of Design and the Farms Security Administration (FSA); the Baruch Collection of Czech photography; the FarEastFarWest collection of Asian photographs; and documentary photographs of Chicago from the Changing Chicago Project. Additionally, Tichy invited a group of international curators and cultural producers (including the editors of ARTMargins Online) to organize a year-long series of digital exhibitions drawn from the MoCP collection for the museum’s new, street-level Cornerstone Window Gallery.

In his most recent project 1979:1-2012:21: Jan Tichy Works with the MoCP Collection, the artist similarly confronts the stability and authority of institutional power, in this case the permanent collection of Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Photography. Like other contemporary artists working with research-based, archival practices, Tichy engages the MoCP collection not as a static repository of objects and information, but rather “as an active, regulatory discursive system.”Okwui Enwezor, “Archive Fever: Photography between History and the Monument,” in Archive Fever: Uses of the Document in Contemporary Art, exhibition catalog (NY: International Center for Photography, 2008), p. 11. This system includes the creation of new interpretive instruments: primary is an exhibition of select photographs from the collection curated by Tichy, including those chosen by the MoCP’s six curators, as well as new works created by the artist in response to the images on view. A group of local MFA students worked with Tichy in redesigning the museum’s website that serves as a publicly accessible archive of its collection of nearly 11,000 images. Collection highlights include works by important figures from the New Bauhaus/Institute of Design and the Farms Security Administration (FSA); the Baruch Collection of Czech photography; the FarEastFarWest collection of Asian photographs; and documentary photographs of Chicago from the Changing Chicago Project. Additionally, Tichy invited a group of international curators and cultural producers (including the editors of ARTMargins Online) to organize a year-long series of digital exhibitions drawn from the MoCP collection for the museum’s new, street-level Cornerstone Window Gallery.

<

Streetscapes: Shadows, Frames, and Altered Views from MoCP, Columbia College Chicago on Vimeo.

In his essay “The Body and the Archive,” Allan Sekula describes the archive as “both an abstract paradigmatic entity and a concrete institution.” “In both senses,” states Sekula, “the archive is a vast substitution set, providing for a relation of general equivalence between images.”Allan Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” in Bolton, R. (ed.) The Contest of Meaning: Critical Histories of Photography (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1992), p. 17. Posing questions about the nature of museum collections and about how museums collect, Tichy creates within the exhibition unexpected equivalences between images based on his own subjective criteria, often arranging photographs in discrete pairs. For instance, the smallest work in the collection, an untitled image of a metal gate by Walker Evans (1928-29), is placed next to Shi Guorui’s aerial view of Shanghai (2005), the collection’s largest. Similarly, Julia Margaret Cameron’s photogravure portrait of Sir John Herschel (1867), the oldest photograph in the collection, hangs in tandem with the museum’s most recent work, Hyers and Mebane’s colorful grid of Las Vegas’ casinos (2012). Elsewhere, the artist establishes more formal kinds of correspondences, as in his pairing of an untitled abstraction by Jaroslav Rössler (1925) and a black-and-white image of Chicago’s Marina Tower (c. 1960) by John Mahtesian.

In his essay “The Body and the Archive,” Allan Sekula describes the archive as “both an abstract paradigmatic entity and a concrete institution.” “In both senses,” states Sekula, “the archive is a vast substitution set, providing for a relation of general equivalence between images.”Allan Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” in Bolton, R. (ed.) The Contest of Meaning: Critical Histories of Photography (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1992), p. 17. Posing questions about the nature of museum collections and about how museums collect, Tichy creates within the exhibition unexpected equivalences between images based on his own subjective criteria, often arranging photographs in discrete pairs. For instance, the smallest work in the collection, an untitled image of a metal gate by Walker Evans (1928-29), is placed next to Shi Guorui’s aerial view of Shanghai (2005), the collection’s largest. Similarly, Julia Margaret Cameron’s photogravure portrait of Sir John Herschel (1867), the oldest photograph in the collection, hangs in tandem with the museum’s most recent work, Hyers and Mebane’s colorful grid of Las Vegas’ casinos (2012). Elsewhere, the artist establishes more formal kinds of correspondences, as in his pairing of an untitled abstraction by Jaroslav Rössler (1925) and a black-and-white image of Chicago’s Marina Tower (c. 1960) by John Mahtesian.

Throughout his curatorial project Tichy offers alternative ways of seeing the MoCP collection; through his own video works, again created in direct dialogue with the photographs on exhibit, he constructs new perceptual experiences. In his video Collection (2012), the artist continues his interest in shadow and light by organizing the digital files of the museum’s 11,000 works from darkest to lightest, then animating them in a rapid-fire sequence (totaling 7.30 minutes) that tests the viewer’s mental (and retinal) ability to code images.

In other works, Tichy transforms images by other artists in the collection. Installation No. 15 (2012) employs similar conceptual and technical strategies as the artist’s earlier Threshold by digitally animating photographs by Aaron Siskind. Amidst the darkness of the museum’s East Gallery, two of Siskind’s abstractions from the 1970s slowly take form, building from dark to light, within two rectangular fields projected onto the wall. Floating near the ceiling of the gallery is one of Siskind’s suspended figures from his Pleasures and Terrors of Levitation series, in which Tichy has reversed the positive and negative tones.

In other works, Tichy transforms images by other artists in the collection. Installation No. 15 (2012) employs similar conceptual and technical strategies as the artist’s earlier Threshold by digitally animating photographs by Aaron Siskind. Amidst the darkness of the museum’s East Gallery, two of Siskind’s abstractions from the 1970s slowly take form, building from dark to light, within two rectangular fields projected onto the wall. Floating near the ceiling of the gallery is one of Siskind’s suspended figures from his Pleasures and Terrors of Levitation series, in which Tichy has reversed the positive and negative tones.

Tichy’s installation renders the two-dimensional photograph as a spatial, even textural environment that both embraces and challenges the fundamental tenets of the photographic medium. Issues of originality and authorship come into play here, as well as in Tichy’s other video works that gather and animate photographs by Andy Warhol, Christian Boltanski, and Barbara Crane. However, unlike conceptual artist Sherrie Levine, for example, whose appropriations of Walker Evans’s FSA photographs critique modernism’s master narrative and the unique aura of the art object, Tichy’s works admit a fond reverence for the artists and images he appropriates. He reclaims the progressive, political principles of modernism that still offer relevance for today. Deeply invested in Moholy-Nagy’s “culture of light,” Tichy creates discursive spaces that perpetually illuminate, while testing the limits of vision.