Irina Botea: It is now a matter of learning hope, at threewalls, Chicago

Irina Botea: It is now a matter of learning hope, threewalls, Chicago, April 26-May 31, 2014

Throughout her practice that spans video, film, performance and installation, Irina Botea appropriates the instruments of mediation that shape the politics of memory to reconfigure the way history frames our contemporary consciousness. Employing strategies of role-playing, reenactment, and recitation, she recasts historical events, often from her native Romania, to remediate political traumas of the past while offering alternate views of reality than those produced by mainstream media.

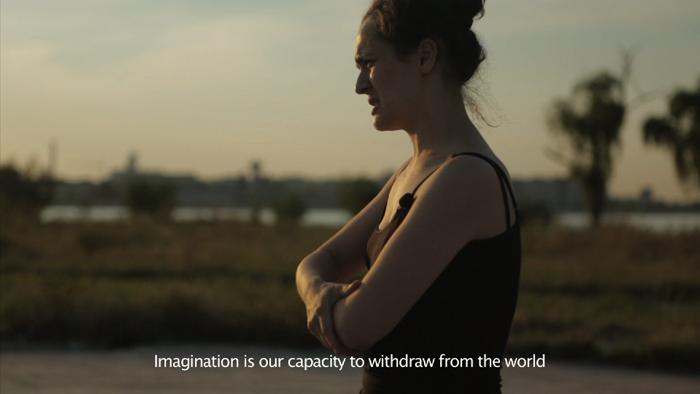

For her recent exhibition at threewalls, It is now a matter of learning hope, the artist presented four videos centered on themes of collective memory and commemoration that reconsider progressive models of political and artistic engagement. The title spins off Ernst Bloch’s The Principle of Hope, the philosopher’s well-known treatise on utopic thought, in which hope or “forward dreaming” actualizes a better life. It is also the title of the first work viewers encountered when entering the darkened gallery. Here, we witness a young woman (Romanian artist Ileana Faur) reciting, in English, fragments of key texts written by, in addition to Bloch, Vilém Flusser, Karl Marx, Thomas More, and Constant Nieuwenhuys.

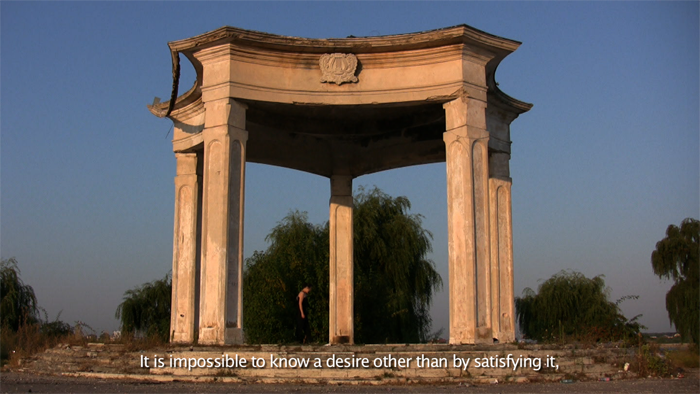

The work begins and ends with Faur standing at the center of a crumbling colonnade, a remnant of Morii Island, in Romania, a utopian architectural project initiated by former communist dictator Nicolae Ceaucescu but never completed. According to Botea, today it has been repurposed by the Romanian public as an open green space, a function that aligns with the utopic perspectives re-presented in the work; thus, Morii Island is a site of both failure and possibility. Pacing back and forth, the actress delivers her lines: “It is impossible to know a desire other than by satisfying it, and the satisfaction of our basic desire a revolution.” “This culture was never capable of satisfying anyone.” However, Faur’s phrases are never seamless — she stumbles, forgets a word or two, consults her notes, gets frustrated and begins to tire. Botea purposefully reveals such imperfections, suspending linear modes of story telling while disrupting the usual lines of authority between director and performer. Such fractures create transparency that allows actors and viewers interpretive agency, a strategy that has become a hallmark of Botea’s filmic practice. Likewise, the artist’s use of rhetorical devices, such as memorization and repetition, questions how systems of belief (and truth) are accepted and understood.

The work begins and ends with Faur standing at the center of a crumbling colonnade, a remnant of Morii Island, in Romania, a utopian architectural project initiated by former communist dictator Nicolae Ceaucescu but never completed. According to Botea, today it has been repurposed by the Romanian public as an open green space, a function that aligns with the utopic perspectives re-presented in the work; thus, Morii Island is a site of both failure and possibility. Pacing back and forth, the actress delivers her lines: “It is impossible to know a desire other than by satisfying it, and the satisfaction of our basic desire a revolution.” “This culture was never capable of satisfying anyone.” However, Faur’s phrases are never seamless — she stumbles, forgets a word or two, consults her notes, gets frustrated and begins to tire. Botea purposefully reveals such imperfections, suspending linear modes of story telling while disrupting the usual lines of authority between director and performer. Such fractures create transparency that allows actors and viewers interpretive agency, a strategy that has become a hallmark of Botea’s filmic practice. Likewise, the artist’s use of rhetorical devices, such as memorization and repetition, questions how systems of belief (and truth) are accepted and understood.

In other works, including Art Historians – a conversation (2014), Botea reconsiders art’s relationship to history by looking to past culturalmovements, in this case the Enlightenment. Set in the Bruckenthal National Museum in Sibiu, Romania, the work offers an intimate view of two female art historians who work at the museum, a collection of sixteenth- to eighteenth-century art amassed by the Romanian Baron Samuel von Brukenthal, once a governor of Transylvania. Created with artist Nicu Ilfoveanu, who did the cinematography, the work belongs to a series of videos that explore the role of memorial houses through the caretakers and guides who frame the public’s experience of the historical figures such spaces immortalize. This includes the earlier film postale (2013), which tours the home-museums of nineteenth-century Romanians B.P. Hasdeu, a writer, and Nicolae B?lcescu, a revolutionary.

In other works, including Art Historians – a conversation (2014), Botea reconsiders art’s relationship to history by looking to past culturalmovements, in this case the Enlightenment. Set in the Bruckenthal National Museum in Sibiu, Romania, the work offers an intimate view of two female art historians who work at the museum, a collection of sixteenth- to eighteenth-century art amassed by the Romanian Baron Samuel von Brukenthal, once a governor of Transylvania. Created with artist Nicu Ilfoveanu, who did the cinematography, the work belongs to a series of videos that explore the role of memorial houses through the caretakers and guides who frame the public’s experience of the historical figures such spaces immortalize. This includes the earlier film postale (2013), which tours the home-museums of nineteenth-century Romanians B.P. Hasdeu, a writer, and Nicolae B?lcescu, a revolutionary.

The women in Art Historians – a conversation have an almost devotional relationship to the historical objects they steward. The first woman, who begins each scene by clapping her hands to signal Botea to start filming, admits her deep reverence for books and the museum’s many illuminations. The other, more self-conscious, looks away from the camera and never directly speaks. In a voiceover, however, we learn that she studied painting and that her profile was once compared to that of Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring (c. 1665), achievements of which she is proud. Together they speak of religiosity in art, truth to nature, artistic talent. “Art is what distinguishes us from animals,” one states. These aesthetic sentiments are formally underscored within Botea’s own filmic process; the majority of the scenes are set in the exterior grounds of the museum, creating a kind of plein air portraiture where her subjects, surrounded by a backdrop of vivid plants and green foliage, are bathed in dapples of warm sunlight.

Botea brings a similar sensibility to the exhibition’s central work, Impersonation (2014), where viewers witness a reenactment of Abraham Lincoln’s final hours, a chiaroscuroed scene reminiscent of Mantegna’s iconic painting The Lamentation over the Dead Christ (c. 1490). Based on the book Lincoln’s Last Hours, written by Charles A. Leale, the Union Army surgeon who tried to save him, four men, all dressed as Lincoln, assume the roles of Leale, two attending doctors, and the dying president. Script in hand, the Leale-Lincoln reads the doctor’s detailed account of the measures used to keep the president alive, as the others enact each procedure. However, disagreement over how the script is interpreted ensues; the other actors correct the Leale-Lincoln’s pronunciation (and sometimes question his authority); they skip over parts deemed too embarrassing; they ask Botea for guidance where to stand. One is struck by the work’s inherent artificiality, which is, at times, quite comical despite the gravity of what is being portrayed and the seriousness by which the impersonators each inhabit the persona of Lincoln. Invoking Botea’s earlier film Auditions for a Revolution (2006), in which non-Romanian actors-speakers reenact the televised events of the 1989 Romanian Revolution, Impersonation similarly juxtaposes real-life historical events alongside mythologized emblems of martyrdom and freedom.

Botea brings a similar sensibility to the exhibition’s central work, Impersonation (2014), where viewers witness a reenactment of Abraham Lincoln’s final hours, a chiaroscuroed scene reminiscent of Mantegna’s iconic painting The Lamentation over the Dead Christ (c. 1490). Based on the book Lincoln’s Last Hours, written by Charles A. Leale, the Union Army surgeon who tried to save him, four men, all dressed as Lincoln, assume the roles of Leale, two attending doctors, and the dying president. Script in hand, the Leale-Lincoln reads the doctor’s detailed account of the measures used to keep the president alive, as the others enact each procedure. However, disagreement over how the script is interpreted ensues; the other actors correct the Leale-Lincoln’s pronunciation (and sometimes question his authority); they skip over parts deemed too embarrassing; they ask Botea for guidance where to stand. One is struck by the work’s inherent artificiality, which is, at times, quite comical despite the gravity of what is being portrayed and the seriousness by which the impersonators each inhabit the persona of Lincoln. Invoking Botea’s earlier film Auditions for a Revolution (2006), in which non-Romanian actors-speakers reenact the televised events of the 1989 Romanian Revolution, Impersonation similarly juxtaposes real-life historical events alongside mythologized emblems of martyrdom and freedom.

Also included in the threewalls exhibition was Photocopy/Fotócopia (2011), a video that performs contemporary models of social activism. Two women sitting on folding chairs face each other and engage in a call-and-response, using words and slogans(in both Spanish and Catalan) taken from the public demonstrations against the Spanish government that occurred throughout Spain on May 15, 2011. The women’s spontaneous criticisms and calls to action, while connected to the vanguard traditions of political resistance that Botea has been engaged with for some time, offered a timely, unintended commentary on King Juan Carlos’s recent abdication from the Spanish throne.

Also included in the threewalls exhibition was Photocopy/Fotócopia (2011), a video that performs contemporary models of social activism. Two women sitting on folding chairs face each other and engage in a call-and-response, using words and slogans(in both Spanish and Catalan) taken from the public demonstrations against the Spanish government that occurred throughout Spain on May 15, 2011. The women’s spontaneous criticisms and calls to action, while connected to the vanguard traditions of political resistance that Botea has been engaged with for some time, offered a timely, unintended commentary on King Juan Carlos’s recent abdication from the Spanish throne.

The success of Botea’s unique practice lies in the artist’s improvisational, participatory approach to her often weighty subjects, combining aspects of cinéma vérité with an informed, critical view of the institutions of image making. Bloch, whose ideas conceptually frame the works on view, saw the emancipatory potential of art and film, what he termed “wishful images,” in the path towards hope. Like him, Botea, a survivor of the failed utopia of communist Romania, sees artistic experimentation and political imagination as central tools for societal transformation.