Interview with Moritz Pankok (Berlin) About Ceija Stojka and the Re-Evaluation of Roma Art

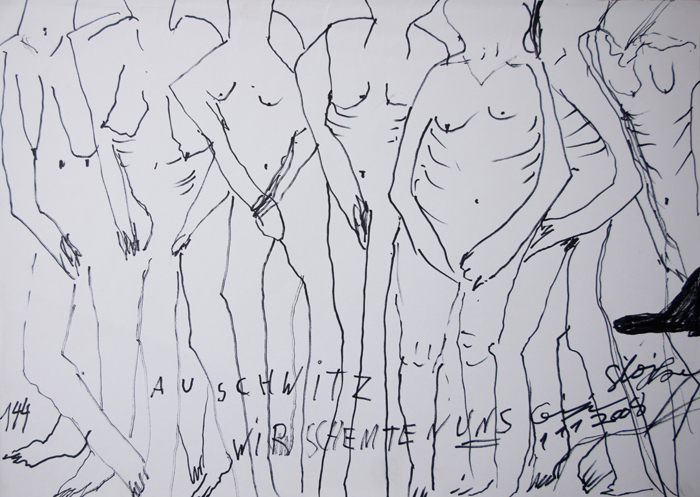

Moritz Pankok is a German scenographer, director, curator and fine artist living in Berlin. A great-nephew of expressionist artist Otto Pankok, who documented Sinti life in late Weimar-era Germany and was labelled a degenerate artist by the Nazis, he is interested in socially engaged art projects. Pankok is the art director of Galerie Kai Dikhas, a private gallery in Berlin dedicated to Roma contemporary art. He was curator of the recent exhibition of work by the Austrian-Romani painter Ceija Stojka, which ran until October 6 at Gallery8, Budapest, the nonprofit counterpart of Kai Dikhas.(We Were Ashamed, Gallery8, Budapest, Hungary, Aug 2-Oct 10, 2014.,Galerie Kai Dikhas and Gallery8 – Roma Contemporary Art Space are organizationally unrelated institutions, founded and operating independently from each other.) Stojka, who died last year, was a survivor of the concentration camps at Auschwitz, Bergen-Belsen and Ravensbrück. The seventeen works in the exhibition We Were Ashamed represented both groups of works that make up her oeuvre: the “dark cycle,” consisting mainly of ink drawings and also some oil paintings that address the traumatic memories of the concentration camps; while the oil paintings of the “bright” series look back on Stojka’s prewar childhood in an itinerant horse-trader family.

Árpád Bak: Ceija Stojka was in her mid-fifties in the late 1980s when she started to paint and write. What made her eventually break this decades-long silence?

Moritz Pankok: I called the exhibition in Budapest We Were Ashamed due to the shame the Sinti and Roma felt about what had happened to them during the Holocaust. Shame was an intentional part of the Nazi treatment of Sinti and Roma, deliberately breaking the rules of Roma society such as the taboo of nudity, or the rules of purity. For the Roma, it became something of a taboo to speak about this. The fate of Sinti and Roma was much neglected partially due to this taboo, and in part due to the people who were in charge of compensating them after the war. In Germany, very often these were the very same people who had been in charge of organizing the Holocaust in the first place. They simply refused testimonies and did not want to let the victims study the archives. With her writing and artwork, Ceija Stojka broke this taboo of silence. She wrote her autobiography, which was published in 1988; soon after, at the age of fifty-six, she began to paint. Obviously, she was not the first to do this because some important Romani activists also went public in a political sense. One person I would mention in this context is Romani Rose who during the early 1980s made political work regarding the genocide of Sinti and Roma. He has been one of twelve Sinties who held a hunger strike at the Dachau concentration camp in 1980. Some of them were survivors of the camps and Rose has been their spokesman. Following this very drastic form of protest, the Central Council of German Sinti and Roma was formed, and German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt was the first state representative to speak of the racial persecution of Sinti and Roma, in 1982. To my knowledge, Stojka and her brother Karl were the first to go public in Austria, where people were particularly silent about this part of history.

ÁB: What was her primary motivation for writing and making art? To work though her trauma or document history?

ÁB: What was her primary motivation for writing and making art? To work though her trauma or document history?

MP: I don’t think that her work was intended to be a private working through of her memories and trauma. It was, from the beginning, a conscious decision to share her experience with the public. She did confront those traumatic memories in order to prevent the atrocities of Auschwitz from eventually waking up again. By saying that “Auschwitz is only sleeping,” she compared the ongoing experience of racism after the war to how the Sinti and Roma were treated before the time of the Nazis in Austria. She wrote this sentence on the back of a painting from 1994. Often there are distinct texts, such as this one, in prose or poetry, on the back of her works.

ÁB: At the 2012 exhibition Requiem, at the French Institute in Budapest, you presented Stojka’s “dark paintings” paired with your great-uncle Otto Pankok’s Roma-themed graphics.(The exhibition was part the cultural events that accompanied the performance of Dutch Sinto musician Roger ‘Moreno’ Rathgeb’s composition Requiem for Auschwitz (2009) in seven European cities between May 2012 and January 2013.) In the current exhibition, you showed paintings from Stojka’s dark cycle alongside works from her “bright” one.

MP: I didn’t exhibit only works from the artist’s dark cycle because, if you look at when Stojka started painting, she created both kinds of works from the same impulse. For me, that is no coincidence since I think they are very much interwoven. For instance, both types of works are usually signed with her signature and a branch of a tree, which is her tribute to a tree in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. She said she ate its rasin and leaves, and that this kept her alive. Her “bright cycle” presents an idealized world of nature scenes and landscapes, childhood memories of Roma wagons, dances and celebrations. Stojka wanted to paint what the Nazis wanted to steal from the Sinti and Roma. I find the image of wind in those paintings very striking. Images of wind are something that one finds in a lot of her works; Stojka once suggested that, for her, the wind stands for memory.

ÁB: For a curator, what challenges are posed by the fact that Stojka’s works are so deeply embedded in history?

MP: I don’t want to overload the exhibitions with historical information, but rather give audiences a direct aesthetic and emotional experience. Also on view at Gallery8 are books on the Roma Holocaust and two documentaries on the artist by Karin Berger. I wanted viewers to hear the voice of Ceija Stojka and to experience her through these documentaries. Following her autobiography there have been quite a few publications about Stojka. Notably there is now the new monograph, Even Death is Afraid of Auschwitz, edited by Berlin curators Lith Bahlmann and Matthias Reichelt, a monumental book about Stojka’s Auschwitz cycle.(Lith Bahlmann, Matthias Reichelt (eds.): Sogar der Tod hat Angst vor Auschwitz [Even Death is Terrified of Auschwitz] (Nürnberg: Verlag für Moderne Kunst), 2014.) Besides the images of 180 artworks, the book also includes a historical essay by Barbara Danckwortt about Stojka’s imprisonment during the Nazi years and a very important text by art historian Tímea Junghaus in which she examines Stojka’s art and puts it into the context of the Roma movement.

At Kai Dikhas Gallery I have curated seven exhibitions with 100 different artworks by Stojka, so the gallery could contribute around sixty photographic reproductions from our archive to the book. I think it is also important to contextualize Stojka’s “bright cycle” paintings, as it would be dangerous to see her just as the narrator of her Holocaust experience and not as a whole person and an artist. The natural landscapes in this group of works should not be seen in the context of naive painting. Rather, they are an artistic expression and synthesis of the new world after Auschwitz. That’s even the title of the work at the entrance of Gallery8. So that’s why I included both cycles together in the Budapest exhibition. There are the dark works, such as the one entitled “Auschwitz – No words,” but Ceija Stojka had the energy for a new rebuilding, including the tremors of the past. She does not say, as Adorno did, that it is impossible to write lyric poetry after Auschwitz. She was a generous person who did not call for revenge but for opening up her closed community. While she painfully shared her memories, she also gave lots of warmth to us.

At Kai Dikhas Gallery I have curated seven exhibitions with 100 different artworks by Stojka, so the gallery could contribute around sixty photographic reproductions from our archive to the book. I think it is also important to contextualize Stojka’s “bright cycle” paintings, as it would be dangerous to see her just as the narrator of her Holocaust experience and not as a whole person and an artist. The natural landscapes in this group of works should not be seen in the context of naive painting. Rather, they are an artistic expression and synthesis of the new world after Auschwitz. That’s even the title of the work at the entrance of Gallery8. So that’s why I included both cycles together in the Budapest exhibition. There are the dark works, such as the one entitled “Auschwitz – No words,” but Ceija Stojka had the energy for a new rebuilding, including the tremors of the past. She does not say, as Adorno did, that it is impossible to write lyric poetry after Auschwitz. She was a generous person who did not call for revenge but for opening up her closed community. While she painfully shared her memories, she also gave lots of warmth to us.

ÁB: Is it possible to trace autobiographical details in the images?

MP: I would hesitate to do this, as it might seem as if the works were meant to be documents of a trial. The German judges and bureaucrats of the 1950s and 1960s would not have accepted them as proof, ironic and absurd as it may seem. They asked survivors for documents but did mostly not accept mere testimonies. Until the 1960s it was argued that in the case of Gypsies it had not even been a racial persecution, because German people had to be kept safe from criminals. However, some works depict recognizable people, such as the infamous guard Dorothea Binz of the Ravensbrück concentration camp. I met a survivor Sintezza who told me of her.(A female Sinti.) The later deputy wardress of Ravensbrück, Binz was very accurate in her hair style and outer appearance. She somehow impressed the Ravensbrück inmates with her appearance but was the most sadistic tormentor of the camp. Stojka depicted her in several works. When I saw one of these works, it reminded me straight away of what the Sintezza had told me about this SS guard. I then also used this artwork and an interview with the other survivor, Bandela Winterstein from Düsseldorf, in a play by our theater company, TAK Theater Aufbau Kreuzberg, about the genocide against the Sinti and Roma.(Das Verschlingen [The Devouring], directed by Anna Koch, dramaturgy and scenography by Moritz Pankok, TAK Theater Aufbau Kreuzberg, September 2013 – October 2014, Berlin, Hamburg.) In Stojka’s Ravensbrück works, one finds an image of a Christmas Eve dinner in 1944. It was a famous solidarity action by the inmates who wanted to care for each other, and was finally permitted by the SS guards. It left a big impression on Stojka. But today, historians would value these images as less important than the rare drawings by prisoners which were drawn inside the camps and survived from the Nazi time. I would say the strength of Stojka’s works is that they deliver a consistent impression of how the camp left a person in fear for decades after. Some would say that the aesthetic is raw. But I think it is delicate at the same time. Stojka has an immense diversity of visual expressions: some works are abstract, some are representational. She often uses the same symbols, such as spirals of barbed wire. There are also images of heaps of dead bodies, and Ceija revealed that she survived by hiding under corpses. The images are drawn with care, and if you compare them it seems as if they are the repeated flashes of one particular memory. She uses the imprint of her bare hands as a proof that she is still alive. I often would not dare to define the camp one particular image depicts, as it is not a specific site, but a consistent, feeling found anywhere.

ÁB: Stojka is one of the most internationally recognized Roma contemporary artists. Besides institutions of Roma art, is she represented in any major public collections of contemporary art?

MP: Yes, the Vienna Museum bought a series of works that is now part of its collection. Two years ago I showed a delegation from the citiy council of Vienna and the museum around in Ceija Stojka’s apartment. She was in the hospital by then. Following that, the delegation decided to help the Stojka family by paying two months’ rent. Luckily, they reversed their opinion and dedicated funds to buy art from the family. Some of these works were included in a large exhibition entitled Even Death is Afraid of Auschwitz dedicated to Stojka recently shown in two venues in Berlin.(Even Death is Terrified of Auschwitz. An exhibition in three parts. Kunstverein Tiergarten | Galerie Nord, Berlin, Germany, June 21-July 26, 2014; Galerie Schwartzsche Villa, Kulturamt Steglitz-Zehlendorf, Berlin, Germany, July 2-August 31, 2014; Ravensbrück Women’s Concentration Camp, Fürstenberg/Havel, Germany, July 13-September 12, 2014.) The monograph mentioned earlier is the catalogue to this exhibition, and this selection of her works will tour Heidelberg and Austria in 2015.

MP: Yes, the Vienna Museum bought a series of works that is now part of its collection. Two years ago I showed a delegation from the citiy council of Vienna and the museum around in Ceija Stojka’s apartment. She was in the hospital by then. Following that, the delegation decided to help the Stojka family by paying two months’ rent. Luckily, they reversed their opinion and dedicated funds to buy art from the family. Some of these works were included in a large exhibition entitled Even Death is Afraid of Auschwitz dedicated to Stojka recently shown in two venues in Berlin.(Even Death is Terrified of Auschwitz. An exhibition in three parts. Kunstverein Tiergarten | Galerie Nord, Berlin, Germany, June 21-July 26, 2014; Galerie Schwartzsche Villa, Kulturamt Steglitz-Zehlendorf, Berlin, Germany, July 2-August 31, 2014; Ravensbrück Women’s Concentration Camp, Fürstenberg/Havel, Germany, July 13-September 12, 2014.) The monograph mentioned earlier is the catalogue to this exhibition, and this selection of her works will tour Heidelberg and Austria in 2015.

ÁB: At the end of Marika Schmiedt’s documentary Vermächtnis/Legacy (2010-2011), Stojka said that the director asked her about her life just in time.(Marika Schmiedt: Vermächtnis/Legacy (2010-2011) http://vimeo.com/76599447.) Stojka died last year, at the age of seventy-nine, surviving her brother Karl by ten years. Does this discourse of historical memory remain a priority for younger generations of Roma artists?

MP: It is not only the question of one generation, as even young Roma artists are dealing with this issue. I work with artists from all over Europe and the lingering impression or memory that the genocide has left with the Sinti and Roma is something that can be traceed throughout the continent. These young artists speak about this issue because it is very deeply rooted in their family experience. The traumatic experience of the Holocaust is alive even with very young Sinti and Roma. Scientific research by Daniel Strauss on young Sinti found that children whose families had more Holocaust victims or who have an otherwise strong link to that history have more problems in school. This research shows that the traces and the impact of the genocide are still alive today.

ÁB: Do the images presented in Stojka’s exhibition at Gallery8 belong to the collection of Kai Dikhas Gallery?

MP: No, all except for one are on loan from Hojda Stojka, the artist’s son. Kai Dikhas Gallery owns an art collection and plans to eventually create a permanent exhibition of Roma contemporary art. The eight artworks by Stojka that belong to the gallery are currently on exhibit at a group show in Germany, near Frankfurt.(Akathe Te Beshen/Here to Stay, Kunststation Kleinsassen, Kleinsassen, Germany, June 8-August 31, 2014.) This exhibition, entitled Akathe Te Beshen/Here to Stay involves thirteen artists, and of the 160 artworks, sixteen are by Stojka. The exhibition is intended to tour. At the end of November we have a presentation of parts of theart show at the State Gallery of Stuttgart.

ÁB: Given her recent exhibitions and the publication of a monographic catalog dedicated to her work, this year seems to be of special significance in the recognition of Stojka’s art.(After this interview took place, in September 2014, a public square in Vienna was named after Ceija Stojka.)

MP: Stojka has been a public figure in Austria, but less so abroad, even if she has had some exposure in Japan and the United States. I think people are discovering her art now. This has to do with the realization that her memory must be kept alive. The survivors die, but their experiences must help shape how we deal with our future. With great fear, we can see the rise of hate and racism anywhere, and we lack voices like Ceija Stojka’s. It seems that awareness that her art must be preserved rose only after she died. When we made our first exhibitions, the team at Kai Dikhas and myself found that people before us had just glued artworks to cardboard in order to exhibit them. Now they are preserved under stricter conditions. Also, the public needed time to recognize to what extent artists of Roma origin contribute to our cultural landscape. And that their art does not just deal with their issues, but that their issues are ours as well. In general, I see a lack of acceptance of Roma artists, who are great, but who are not received according to the quality of their work. This is at the core of what we are aiming to do with the Gallery Kai Dikhas.

MP: Stojka has been a public figure in Austria, but less so abroad, even if she has had some exposure in Japan and the United States. I think people are discovering her art now. This has to do with the realization that her memory must be kept alive. The survivors die, but their experiences must help shape how we deal with our future. With great fear, we can see the rise of hate and racism anywhere, and we lack voices like Ceija Stojka’s. It seems that awareness that her art must be preserved rose only after she died. When we made our first exhibitions, the team at Kai Dikhas and myself found that people before us had just glued artworks to cardboard in order to exhibit them. Now they are preserved under stricter conditions. Also, the public needed time to recognize to what extent artists of Roma origin contribute to our cultural landscape. And that their art does not just deal with their issues, but that their issues are ours as well. In general, I see a lack of acceptance of Roma artists, who are great, but who are not received according to the quality of their work. This is at the core of what we are aiming to do with the Gallery Kai Dikhas.

ÁB: Public art museums are places of national self-representation. Growing anti-Roma sentiments all over Europe might give an incentive for these institutes to strengthen their commitment to representational adequacy. Does the emergence such of sentiments also pose challenges for applying this principle?

MP: In Romania, one of the artists we work with, George Vasilescu, ran into trouble in late July this year for having an exhibition in a state museum.(Confluence, influen?e – în art??, Muzeul Na?ional al ??ranului Român [Romanian Peasant Museum], Bucharest, Romania, July 2-8, 2014.) He had a solo show with fifteen paintings depicting famous Romanian Roma musicians. The politician Bogdan Diaconu of the ruling Social Democratic Party called for the director to step down. The director even received a death threat. People wanted to destroy artworks instead of being proud of what Roma contribute to Romanian culture.

ÁB: In the collection of the Hungarian National Gallery there is a painting by István Szentandrássy, a contemporary Hungarian artist of Roma origin.(In 2013 Ludwig Museum – Museum of Contemporary Art (Budapest, Hungary) purchased seven paintings by Hungarian Roma artist Omara, with the assistance of the National Cultural Fund and a further work of hers became part of the museum’s collection as a gift from the European Roma Cultural Foundation. Ludwig Museum – Museum of Contemporary Art, a central government-funded body, collects both international and Hungarian contemporary art.) Who else would you like to see in this collection?

ÁB: In the collection of the Hungarian National Gallery there is a painting by István Szentandrássy, a contemporary Hungarian artist of Roma origin.(In 2013 Ludwig Museum – Museum of Contemporary Art (Budapest, Hungary) purchased seven paintings by Hungarian Roma artist Omara, with the assistance of the National Cultural Fund and a further work of hers became part of the museum’s collection as a gift from the European Roma Cultural Foundation. Ludwig Museum – Museum of Contemporary Art, a central government-funded body, collects both international and Hungarian contemporary art.) Who else would you like to see in this collection?

MP: It is interesting that in Hungary, the political emancipation movement of Roma developed alongside the discovery of art made by Roma. The Roma Parliament and Romano Kher have gathered a huge collection of painters of Roma origin.(The Hungarian Roma Parliament is a non-governmental organization founded in 1991.,Metropolitan Municipality Gypsy House – Romano Kher (Budapest, Hungary). Founded in 1987, this was the predecessor to the Budapest Roma Educational and Cultural Center (FROKK), which replaced Romano Kher in 2010.) The most important Roma activists, such as Ágnes Daróczi, her daughter Katalin Bársony, or Jen? Zsigó organize exhibitions and art collections, while Timea Junghaus is an art historian. So the political work goes along with the art. However, it is worrying to see that in Hungary in recent years the achievements of the Roma emancipation movement of the last twenty-five years of have been erased or, in the case of the Roma Parliament, are in danger of being erased.(In 2012 the Municipality of District 8 of Budapest did not renew the office lease agreement with the Roma Parliament, in spite of the NGO having settled its arrears.) Two artists who are important in the context of the Roma emancipation movement are the painters Tamás Péli and János Balázs.(Among the major public institutions of art and culture, Tamás Péli and János Balázs are represented only in the Roma collection of the Museum of Ethnography, Budapest.) They should be in this collection for sure. In Hungary there are so many talented artists of Roma origin, also of the younger generation.

ÁB: Thank you.

This conversation took place via Skype and e-mail in August 2014. In a shorter form, the interview was published, in Hungarian, in the online edition of the political-cultural weekly Magyar Narancs.