Interview with Monika Fabijanska on Women at War

Women at War gathers the works of twelve Ukrainian artists who employ a variety of media to address the Russian war against Ukraine, from its beginning in 2014 to the full-scale invasion in February 2022, through the lens of gendered experience. The exhibition explores the struggle for Ukrainian independence and women’s equality against the backdrop of the war and its impact on both the national and individual psyche while giving voice to women as narrators of history and agents of change. Curated by Monika Fabijanska, Women at War premiered at Fridman Gallery, New York, in the summer of 2022, and continues its North American tour through 2025.(Woman at War tour: Eastern Connecticut State University, Willimantic, CT, fall 2022; Weselyan University, Middletown, CT, fall 2022; The Art Gallery of Stanford in Washington, Washington, DC, spring 2023; Florida State University Museum of Fine Arts, Tallahassee, FL, July – October 2023; University of Manitoba School of Art Gallery, Winnipeg, MB, February – April 2024; Chicago Cultural Center, Chicago, IL, August – December 2024; North Dakota Museum of Art, Grand Forks, ND, spring 2025; and San Diego State University Art Gallery, CA, fall 2025.) I recently spoke with Fabijanska, known for her critically acclaimed exhibitions focusing on women and women’s art, about the challenges of organizing an exhibition about war alongside the show’s many themes of loss and resiliency, national identity, and feminism.

Susan Snodgrass: Several of the exhibition’s works serve as documents of the systematic erosion of daily life in Ukraine since the war began in the Donbas region, while some of the most recent works record the violence, rage, and fear wrought across the country. What does this traveling exhibition reveal about the role of Ukrainian women and female artists throughout this almost nine-year period of war and turmoil?

Monika Fabijanska: I curated this exhibition to show U.S. audiences the war through the eyes of the best artists in Ukraine. As a feminist art historian, I wanted to learn what an image of war would emerge from artworks by women. I have been curating around subjects central to women’s art – such as rape and ecofeminism – that have been missing from mainstream art or conversation. In this case, the subject is one of the oldest themes in art and literature as war is a central event in human history. But history has been painted and written about almost exclusively by men. What if we give a platform to women narrators?

If I had any expectation, I thought I might find imagery of women in combat. Women have joined the military in drag for centuries; in Eastern Europe, their involvement was especially significant (800,000 women fought in the Red Army, and in both the Soviet Union and other occupied countries, they joined partisans). Although they comprise 22-25% of today’s Ukrainian army, I didn’t find images of women warriors in art. It seems that women artists rarely focus on combat as the essence of war – or at least this survey of works by several dozen artists from one country, relating to one war, shows that Ukrainian women artists rarely depict military action. What they offer instead is feminist historiography.

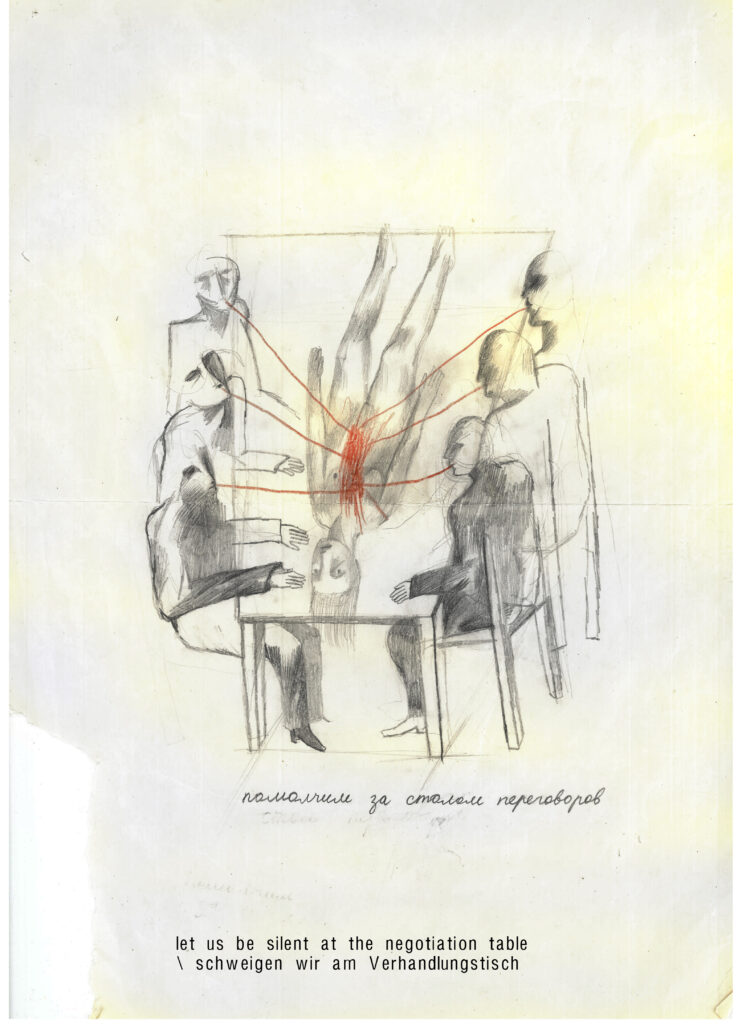

Dana Kavelina, let us be silent at the negotiation table (Communications. Exit to the Blind Spot series) (2019). Graphite and colored pencil on paper, 16.5 x 11.75 in. Courtesy of the artist and Fridman Gallery, New York.

Many denounce traditional representations of war, its glorification and heroism. Such criticism permeates the works and statements of Ukrainian artists Yevgenia Belorusets, Alevtina Kakhidze, Dana Kavelina, Alena Grom, Lesia Khomenko, and Anna Scherbyna. Some, like Khomenko and Scherbyna, subvert historical war painting. Kavelina placed her small unframed drawings of raped women among large Soviet military paintings at the Kmytiv Museum in 2019, writing that victors’ stories are linked by women’s bloody lingerie. In her radical vision of feminist historiography, she proposes that history also be written by victims of war (including women, children, the elderly, the poor, and ethnic minorities). Grom declares that war has no winners, only those who survived, and Belorusets titled her series of photographs of Donbas miners Victories of the Defeated (2014-2017). While Kavelina’s and Grom’s artworks show the wartime reality of women and children, including rape, childbearing and child-rearing in active war zone, Belorusets and Kakhidze shed light on social groups that had been marginalized and became invisible during the war in Donbas: miners, retirees, and the Romani minority. Belorusets proposes a radical fragmentation of her image-and-text “stories” as an attempt at objective representation of wartime reality. Resisting narration that could serve war propaganda, she distills human dignity from the life of people working in the war zone, showing glimpses of their everyday life: labor, work conditions, fears, simple joys, and the sense of community – rather than depicting fights surrounding the mines. These are examples of what I see as feminist historiography, and works by these artists made me fantasize that perhaps if women wrote history, war would not have been its central event.

Yevgenia Belorusets, Victories of the Defeated (2014-2017). Photographs and text. Courtesy of the artist.

Most of these artists are also activists – Zhanna Kadyrova and Lesia Khomenko participated in the 2004 Orange Revolution when they did their first project as part of REP Collective. Khomenko also participated in the 2014 Revolution of Dignity when, during violent clashes on Maidan Square in Kyiv, she drew her famous portraits of the fighters. In the wake of the post-Maidan decommunization laws (passed in 2015), Belorusets and other artists took a “historiographic turn,” focusing on inconvenient communist legacy and marginalized subjects of history, and engaged in heated debates about Ukrainian national identity. Scherbyna’s conceptual miniature watercolor landscapes depicting the devastation of Donbas were inspired by her travels with Vostok SOS human rights monitoring missions from 2016 to 2019. Kakhidze has served as an UN Tolerance Ambassador in Ukraine since 2018.

So, the main role of women artists during war is the same as the role of men: to be chroniclers. Yet, their perspective differs significantly – due to different experiences. Even though many women serve in the Ukrainian army, for most of society gender roles in wartime remain traditional: men are supposed to kill and die; women – to play supporting roles in the army, take care of children and the elderly, often becoming refugees or victims of torture and rape, impregnated in the name of nationalism that sees them as motherboards for a nation. Women artists wrestle with depicting women’s victimhood, not to reinforce stereotypes. Seeking to define women’s agency in wartime, Kavelina goes so far as to propose that, paradoxically, it lies in their refusal to participate in the reproduction of violence – that is, in their own violent deaths.

SS: In addition to works that perform an almost documentary function, some of the exhibition’s series-based works are diaristic, revealing a personal view of the physical and psychological impacts of war. What do these more subjective works reveal about Ukrainian nationhood and identity, female and otherwise?

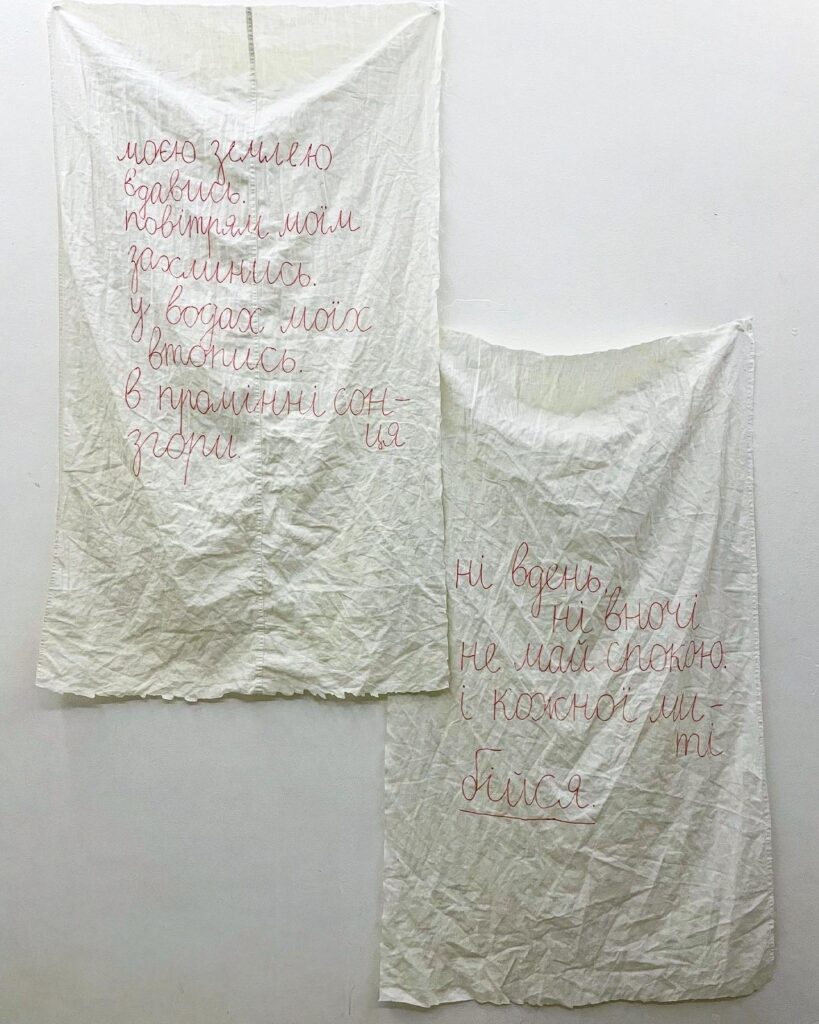

Olia Fedorova, May You Choke on My Soil (Tablets of Rage series) (2022). Text, felt pen on bed linens, 36 x 21 and 35 x 20 in. Courtesy of the artist.

MF: There is no one answer to this question; even among just twelve artists there is a great variety of voices. Three of four diaristic accounts are deeply personal, but only one centers solely on the impact of war on an individual. Kateryna Yermolaeva documents her identity crisis triggered by the war in photographs showing the artist dressed up in various gender roles, sometimes in drag, sometimes as if losing herself. Olia Fedorova’s poems written on bed linens and pieces of cloth while hiding in a cellar during the Battle of Kharkiv are a harrowing document of a mental crisis. Recording deeply personal emotions, ranging from fear to rage, from despair to hope, Fedorova chooses the form of a magic spell. And yet, she clearly curses the enemy in the name of the Ukrainian people, shocked by a brutal land invasion but desperately fighting back. In the last poem, addressed to God, she hopes for a life free from the poison of anger.

The other two diaries offer a wider perspective. Alevtina Kakhidze uses the feminist tenet “the personal is political” in her series of drawings narrating five years of phone conversations with her mother (2014-2019) to illuminate the situation of more than a million Ukrainian retirees who stayed in the separatist Donetsk People’s Republic. In order to collect pensions, they had to cross military checkpoints in the war zone to the territory controlled by Ukraine. Kakhidze‘s well-known series helped bring awareness why some elderly people in Donbas wouldn’t leave their land, homes, and animals.

Vlada Ralko, Lviv Diary No. 20 (2022) Ink and watercolor on paper, 11.5 x 8.5 in. Courtesy of Voloshyn Gallery and Fridman Gallery.

Lastly, Vlada Ralko’s Lviv Diary (2022) is personal only in that it is a record of the artist’s emotions, while she draws well-known events from the war. Ralko started it in Lviv, less than 50 miles from the Polish border, where she was safer than in Kyiv in the first days of the war. In highly symbolical drawings, we recognize actual war crimes committed by the Russians. The massacre in Bucha in March 2022 is represented by a tortured figure whose hands are tied behind their back and figures of raped women, while the March 16, 2022 bombing of the theater in Mariupol, used as an air raid shelter by hundreds of civilians and clearly marked “CHILDREN” – represented by the figure of a child pierced by a bomb. Ralko often uses Christian symbols indicating martyrdom, or symbols of Tzarist Russia (two-headed eagle) and the Soviet Union (red star, hammer and sickle), pointing to the centuries-long imperial oppression of Ukraine by Russia. Her drawings of tortured women point to the connection between national identity and the perception of women’s role in society.

SS: How does one organize an exhibition about war in the midst of a war? What challenges did you face?

MF: It was truly and only possible thanks to Fridman Gallery in New York. Only a commercial gallery could organize such an exhibition at a moment’s notice – a museum needs years to undertake research of an unrepresented culture. Two weeks after the war broke out, Iliya Fridman asked if I would curate an exhibition of Ukrainian artists instead of the show I had already prepared for the gallery. Despite initial reservations, I recognized that we had a unique opportunity to organize an exhibition of the best Ukrainian artists, almost immediately. We had a Ukrainian partner – Voloshyn Gallery from Kyiv – who had collaborated with Fridman before and now proposed to co-organize an exhibition with some of their artists. And not only am I familiar with the region’s history and geopolitics (I can also read some Ukrainian), but I had already planned to travel to Warsaw and Venice in April, and realized that once there, I would be able to arrange getting the works from Ukraine to Poland through my contacts. That required having the concept, the list of artists, and the checklist of the show finalized before my departure.

It took much longer to get works from various parts of Ukraine, where international shippers ceased operations, to Warsaw than I thought. In the meantime, many artists moved to the West. Eventually, works were shipped from several cities in Europe, those coming from Ukraine came via my family in Warsaw, some artists brought their works to Venice, and photographs were printed in New York. Venice proved important – this is where I met Kakhidze, Belorusets, and Kadyrova in person. In Warsaw, I did a studio visit with Khomenko. All invited artists participated in the show with the works I had selected in early March, adding three more artworks newly created. The exhibition opened on July 6, so we had to organize it in three and a half months including research, concept, artists and artworks selection, international shipping – also from the interritory of war– printing photography, framing, and writing the press release, catalog essay, and wall labels.

Yet throughout this bustle, requiring fast and frequent communication with the artists, the most difficult were periods of silence. My messages were often left hanging without a response – sometimes a few days, sometimes even two weeks. Ocassionally, I could guess what was going on, but usually I had no idea. Between March and June, most of these women became war refugees, seeking a place to go to, evacuating artworks and children or elderly parents. Some traveled back and forth. Some were hiding from bombing in cellars. Our broken exchanges became tokens of human connection.

I’ve never had to engage so many emotions in any curatorial project. Who wants to know the first names of the war? And yet, I thought it would be important to make them known in New York – a city that has never had a group exhibition of the best contemporary artists working in Ukraine – and in the U.S., where generally, Ukrainian culture is not distinguished from Russian, and where most academic departments of Slavic Studies have in fact been Russian Studies departments.

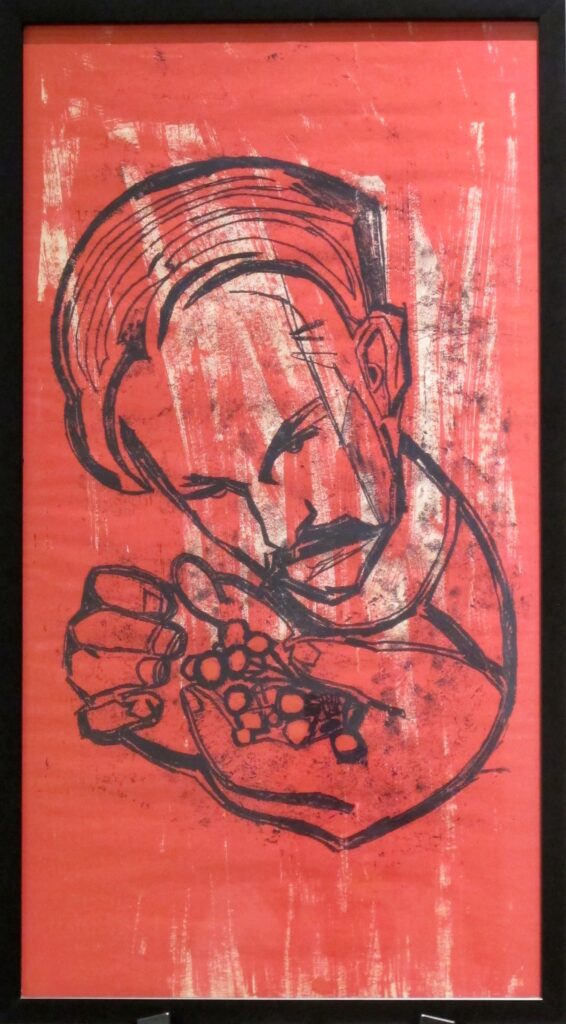

Alla Horska, Portrait of Ivan Svitlychny (c, 1963). Linocut, 28 x 15 in. Courtesy of the Ukrainian Museum in New York.

SS: How were artists selected? Why did you include the historical work Portrait of Ivan Svitlychny (c. 1963) by Alla Horska?

MF: Including Alla Horska’s work was one of my first thoughts. It allowed us to present contemporary artists in the context of the legacy of women’s art and political activism in Ukraine. Horska was an artist and human rights activist who since 1960, together with poet Ivan Svitlychny, belonged to Shistdesyatnyky (The Sixtiers) – a dissident movement of writers and artists who rejected socialist realism and dedicated themselves to Ukrainian democratic and national revival. They played a fundamental role in upholding the Ukrainian dream of independence. In 1970, Horska was murdered at the age of 41, probably by the KGB. Her art helps show the complexity of Ukrainian postcolonial identity and politics. Expelled from the Artist’s Union of the Ukrainian SSR in 1964, she later collaborated on monumental Soviet mosaics and frescoes on public buildings in Donbas – art that the post-Maidan Ukrainian government wanted to destroy as part of the decommunization campaign. She is the Frida Kahlo of Ukrainian art, inspiring artists who try to reconcile the legacy of socialism with national culture. We had Horska’s portrait of Svitlychny on loan from the Ukrainian Museum in New York, but had to returned it. For the remainder of the exhibition tour, Horska’s 1967 sketch for the mosaic Blooming Ukraine in Mariupol will be included.

Research for the exhibition had to be done very fast. Selecting artists was based on a wide range of multinational, publicly available online sources, most listed in the catalog. Some of the best were critical and analytical texts covering the development of art in post-communist Ukraine written by Ukrainian authors and published by the art magazine BLOK in Poland; the Secondary Archive – a project of the Katarzyna Kozyra Foundation that maps women artists from Eastern Europe; and the book Why There Are Great Women Artists in Ukrainian Art (Iakovlenko, Łazar, 2019). However, key for selecting artworks was my familiarity with cultural and historical context for the works, and the complexities of current politics in the region, including my personal experience of the post-communist social transformation. After having selected artworks, I then interviewed all artists.

SS: What are the parallels and differences between feminism in Ukraine and feminist art practices across Central and Eastern Europe and elsewhere?

MF: Communism promised equality to all, including women. Indeed, the Bolsheviks granted them the right to vote in 1917, the right to divorce in 1918, and abortion on demand in hospitals in 1920. Yet, abortion was soon delegalized under Stalin, and the Soviet Union, despite enforcing atheism, became conservative culturally. Even though women could join the army during World War II and by the 1960s state-sponsored childcare made it possible for more than 75 percent of women to be employed, they still had full responsibility for household and childcare. The laws giving women freedom to work, or die on the front, reflected current needs of the Soviet empire – first to grow its workforce, then the population, then the army, then women had to replace men lost during the war in workforce, and so on… Equal pay was a fiction because women mostly worked in lower-paid jobs. The Soviet Union was also the first country where women could be elected, yet they were almost absent from the party elite.

The progressive language of communist propaganda drilled into the minds of three generations made women in Eastern Europe believe that they were equal to men. Even if they actually worked double duty, and the misogyny of societies under communism was similar to elsewhere, the sole fact that they could work and have social roles besides mothering and housewiving played a crucial role in women’s perception of their freedom and equality. They never questioned why socialist realist painting, public sculpture, and mosaics depicted representations of masculinized women working to build socialism, but no feminized men.

Despite local variations, such as the role of religion, the situation of women in other communist countries was largely similar. Feminism was thought to be a bourgeois issue and met with distrust and criticism from both the Communist Party and society. For example, in Poland under communism, those few women artists who achieved mainstream success distanced themselves from the label that was damaging in the eyes of men and women alike.

After the fall of communism, many women in Eastern Europe embraced what they perceived as a new freedom – staying at home with children. It took a generation to realize that misogyny permeates human culture, whether under capitalism or communism. Transformation brought new challenges, such as trafficking women. Oksana Chepelyk, whose video is included in Women in War, was probably the first Ukrainian to embrace the term feminist artist – as late as in the 1990s.

SS: The last two years have seen unprecedented losses for women on a global scale, including current violations against women in Iran, the erosion of women’s rights in Afghanistan, and the overturning of Roe v. Wade. Your curatorial work has never shied from addressing difficult (and necessary) subjects, whether war, images of rape in contemporary art (The Un-Heroic Act, 2018), or environmental issues and climate change (ecofeminism(s), 2020). How do feminist art practices make visible these injustices while offering a sense of agency and hope?

MF: We live in times of radical cultural and social change across the globe, and the landscape of feminist and women’s art is nuanced, but despite cultural and political differences, most women want to be free from patriarchal oppression. Trying to achieve that, feminism has been the true avant-garde in the last fifty years, showing us a direction that we tend to call “radical care.” Its emanations are the art of the remediation of environmental degradation proposed by ecoartists, mostly women, since the 1980s, or feminist historiography proposed by these Ukrainian artists who place humans (and also animals or plants), not a nation, at the center of our concerns.