Interview with Geta Brătescu (Adriana Oprea)

For most of her career Geta Bratescu worked under communism in Romania. Bratescu studied at the Faculty of Letters and the Institute of Fine Arts in Bucharest, where her master teacher was Camil Ressu. Her body of work comprises drawing, collage, engraving, tapestry, objects, photography, experimental film, video and performance. She is also the author of several books — documents of daily studio notes, reflections about art and travel experiences. Already an established artist in 1989 when the communist regime ended in Romania, Bratescu continued to work and participate in important local exhibitions such as The Gender of Mozart (Artexpo, Bucharest, 1991) or The Experiment in Romanian Art after 1960 (Soros Centre for Contemporary Arts, Bucharest, 1996), as well as in the international exhibitions In Search of Balkania (Neue Galerie Graz am Lanesmuseum Joanneum, Graz, 2002) and Gender Check. Femininity and Masculinity in Eastern European Art (Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig, Vienna, 2009). Her recent international recognition has provided a basis for the reevaluation of her more experimental work within the framework of conceptual practices in Eastern Europe. Bratescu lives and works in Bucharest.

Adriana Oprea: You once wrote that you belonged to a lost world, a world that has disappeared.

Geta Bratescu: I come from Ploie?ti, Romania. My father came from the mountains; he was from the southern part of the country, but from its mountainous region. My mother was a native of Ploie?ti. She came from a very modest family; they were great people. My grandfather had a coppersmith workshop where he worked brass. I remember his workshop; he had a big furnace to heat the metal in, and he used to wear a green apron. He was making large brass pots. I still have a few wonderful ones. You can sense the traces of the hammer. My father was a pharmacist, and owned a drugstore acquired with his own savings. He was the son of a peasant, and when he was twelve years old he came to Ploie?ti, went to the Petru and Pavel High School there, and told the director: “I want to get an education.” This was before World War I. The school accepted him on the condition that he help the director’s wife with her house chores. This is how he was able to attend high school. He was a very good pupil and was offered scholarships from two universities in medicine and pharmacy. He enrolled in both, taking jobs in order to pay the tuition for the second one. Eventually, he had to give up medicine, as he had to keep his job and this was too much for him. But he graduated in pharmacy. This is how he was able to move on.

AO: All of your books include excerpts from your diaries, daily notes, reflections and recollections. In them, you talk about this lost world, the Romanian society before and during the interwar period, which gradually disappeared and was transformed and disrupted with the onset of communism in the 1950s. How did you live through this change? How did you experience the crisis of that world you belonged to, the world of your childhood and early youth?

GB: It was 1945, and I had just enrolled in the university at that time. I was attending courses at the Art Institute and the Faculty of Letters in Bucharest, until, without too much fuss, I was expelled from the Art Institute. It was a time of purges. Camil Ressu, my teacher at the Art Institute, knew my work and never criticized me; he appreciated my drawings. But the official commission that evaluated our studio work did criticize me and suggested my expulsion. The real problem was my father, a capitalist, in their terms. I was deeply affected, but I went on working and enrolled again in 1969, when I was already working for Secolul 20 magazine. I needed a degree, and I wanted to work from a live model, to go through the entire art school training. So I would have a degree. Things hadn’t changed much in the academic system between 1945, the year of my first enrolment, and 1969, the year of my second one. Throughout this time I stayed in Bucharest, and my family helped me a lot. I was working and going to exhibitions. I was making book illustrations and layouts.

Working for Secolul 20 magazine and with people like ?tefan Augustin Doina?, the editor-in-chief, mattered and still matters a lot to me. Doina? asked me to make the illustrations for Goethe’s Faust, which he had translated. The illustrations for Faust are an important part of my work; one could make an exhibition just with them. I truly lived this book; it was a great experience. I was lucky because Doina? didn’t expect me to follow the lines in conceiving the illustrations. He let me do what I wanted. Today, I continue to work for this magazine, which has now become Secolul 21. But now there is no money, and they can’t publish more than three issues per year and this is done with huge efforts. Back then, in communist times, Secolul 20 was financed by the Ministry of Culture. It was a propaganda factor, meant to show that under communism we were not living in complete darkness. Secolul 20 was distributed abroad quite widely. When they travelled, the communist activists in charge of culture would take a few copies to offer them around. When it appeared at kiosks, people would queue in order to buy it. Thanks to Dan H?ulic? and to Doina?, Secolul 20 was a free world: we could publish foreign literature, art historical images and reproduce works by Romanian artists with major exhibitions. Secolul 20, now Secolul 21, is my second child. I love this art-editorial job.

AO: At this time, which is just after 1945, had socialist realism already entered the educational system and the art world? What was the outlook?

GB: Education remained largely traditional: drawing from live models and sketching. We had a very good teacher, the artist Camil Ressu. Socialist realism came after my first brief stay at the art school. Ressu had lost his authority by then.

GB: Education remained largely traditional: drawing from live models and sketching. We had a very good teacher, the artist Camil Ressu. Socialist realism came after my first brief stay at the art school. Ressu had lost his authority by then.

AO: What was your relationship with the Romanian Union of Fine Artists before you became a full member and started exhibiting in its spaces, the only place where artists could show their work in communist Romania?

GB: I used to go to their meetings, Marxist educational meetings, as we all had to. Surprisingly, some of them were interesting because they brought in invited lecturers. I was just a candidate to full membership in the Union of Fine Artists, but I profited enormously from free travel within the country, requested by the Union from artists in order for them to become acquainted with the life of the “socialist man,” i.e. the worker, the peasant, the common person building socialism. I have works inspired by this experience. The factory workers would keep a stool for me in the factory hall, and I would sit and observe what went on there, working along with them. I not only went to steelwork plants, but also to the Danube Delta. I will never forget the homage of a fisherman who, in learning why I was there, laid a giant fish at my feet.

AO: Besides the emotional benefit of these trips, was cultural and intellectual life a refuge from the ideological and political oppression under communism?

GB: Today, everyone sees things as having been utterly politicized. When I think how much it meant for me to attend the conferences given by George Calinescu during that harsh communist era of the 1950s, I do not think of this experience as a refuge. It was what it was. I showed my works at the official salons, but on occasion I also made illustrations for this or that obscure officially approved text for the press. In France, for instance, artists had a leftist mentality. So things could circulate somehow between a communist country like Romania and other countries. It was not as bad nor as politicized as it appears now. In my view it is the human being that matters. The Union had subscriptions to French art magazines, which were received on a regular basis even then. I would go to the Union and would find information about everything. I also used to go to the German [Goethe] Institute to watch movies. We had been warned that those who went to foreign cultural institutes would be noted.

AO: Actually, communism was not the same throughout the four decades of its domination in Romania. It was quite a long way from the harshness and terror of the fifties under Gheorghe Gheorghiu Dej, when communism was imposed by force in Romania, to the ideological softening and “openness” towards the West inaugurated by Nicolae Ceaucescu in 1965, to the “tightening of the screw” in Romania during the last decade of Ceaucescu’s regime during the 1980s. Let’s take them one at a time. When socialist realism ceased being the official model of artistic production in Romania, it was said that during the 1960s and the ’70s one could find in the studios of many Romanian artists — often aligned to a well-behaved, neutral, often decorative pictorial or sculptural modernism — surprising new things, wholly atypical for their work and style. The “opening” brought about a period of experimentation in Romanian art, and this was very important in the development of many young artists at that time, including Horia Bernea, Ion Grigorescu, Paul Neagu and Pavel Ilie. It was the period when Richard Demarco visited Romania and invited some of these artists to the Edinburgh Festival. Virtually any artist could travel abroad. Many Romanian artists and writers emigrated to the West during these years. As for you, you were making film and photography at the time, such works as The Studio (1977), The Hand of My Body (1977) and Towards White (1975).

GB: True, communism was not the same at all times. To put it in one word, during the 1970s film and photography were in fashion. But all in all, it was a good thing; it was an experience. All my photographs were taken by my husband Mihai Bratescu. He had an old, but gorgeous Rolecom camera.

AO: You wrote somewhere that you were never a photographer in the traditional sense, “someone who enters a space and takes pictures.” You were never behind a camera.

GB: Yes, because I don’t know how to do it. One has to be good at it. But I like to play, to be in front of the camera, instead.

AO: One could say that throughout your work the protagonist often seems to be a staged self, a theatrical ego, a mask and role-playing that fictionalize the self. It seems to me that before any other influence, there was a cultural phenomenon close at hand that mattered a great deal to the Romanian artists active back then, and to you as well. Romanian theater was at its peak in the 1970s and 1980s. Many productions became legendary, this time period produced “the golden generation” of Romanian actors, as well as remarkable stage designs commented upon in the cultural press.

AO: One could say that throughout your work the protagonist often seems to be a staged self, a theatrical ego, a mask and role-playing that fictionalize the self. It seems to me that before any other influence, there was a cultural phenomenon close at hand that mattered a great deal to the Romanian artists active back then, and to you as well. Romanian theater was at its peak in the 1970s and 1980s. Many productions became legendary, this time period produced “the golden generation” of Romanian actors, as well as remarkable stage designs commented upon in the cultural press.

GB: I used to go to the theater a lot. I was acquainted with director Andrei ?erban, who directed Medea and belongs to a younger generation. He came to my studio. It impressed me immensely, but I don’t remember if my Medea drawings were made before or after his production. Medea is an important work of mine. Of course, he did not take his inspiration from me; Greek mythology is so broad. The play impressed me. This whole story of Medea was in the air. And it’s true that we were living in a fantastic atmosphere within the cultural milieus of that time in Romania.

AO: Like other artists, you travelled before 1989, in those moments when a less tight political control allowed it. Your books, From Venice to Venice (1970), or Wandering Studio (1994), recount in detail your revelations, discoveries, the joy of learning and seeing, of being in touch with the broad history of art while travelling. You speak in these books about museums, monuments, and cities.

GB: I was filled with enthusiasm when I travelled to Greece. This is a world I feel I belong to. I travelled before 1989, but I wasn’t able to sort out the revelations I had then. When I was in England, I discovered Constructivism, of which there was a lot around. I recall liking Charles Rennie Mackintosh; I was very taken by his meticulous precision. The chair I am sitting in now is a genuine Thonet. While visiting a museum in London I saw such a Thonet chair exhibited in a glass case. Mine is marked by authenticity; it comes from my family. This kind of furniture was on the market back then; my family used to buy it. They are very comfortable — a beauty!

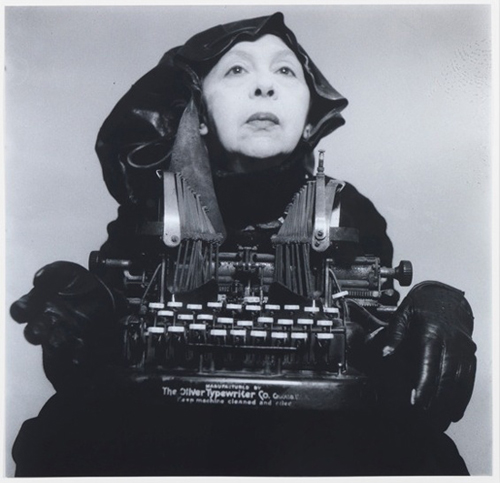

AO: Lady Oliver and Sir Thonet are a couple whom you’ve played in several of your works, including an artist’s book, and the installation Lady Oliver and Sir Thonet (1991). In a superb photograph, Lady Oliver in Traveling Suit (1985), an old Oliver typewriter, much like the Thonet furniture, is an object that serves as a sumptuous necklace to Geta Bratescu’s alter ego. These props nostalgically evoke the same lost world we were talking about earlier, a world populated with knights and ladies.

AO: Lady Oliver and Sir Thonet are a couple whom you’ve played in several of your works, including an artist’s book, and the installation Lady Oliver and Sir Thonet (1991). In a superb photograph, Lady Oliver in Traveling Suit (1985), an old Oliver typewriter, much like the Thonet furniture, is an object that serves as a sumptuous necklace to Geta Bratescu’s alter ego. These props nostalgically evoke the same lost world we were talking about earlier, a world populated with knights and ladies.

GB: If I look at myself from the outside, I see all of this as a process of recollection. I love such things as the Thonet chair; they are well made, inspire trust, and have a strong presence. During communism many people threw away objects like these, or set them on fire. Such a shame! These objects have character; they are endowed with a presence that inspires longevity and reliability.

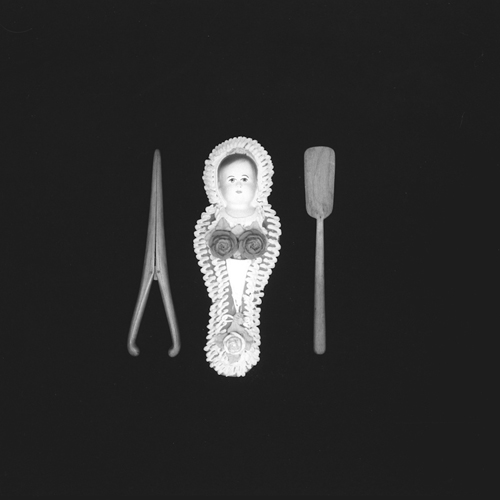

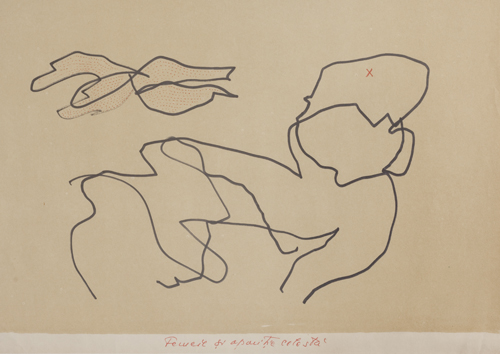

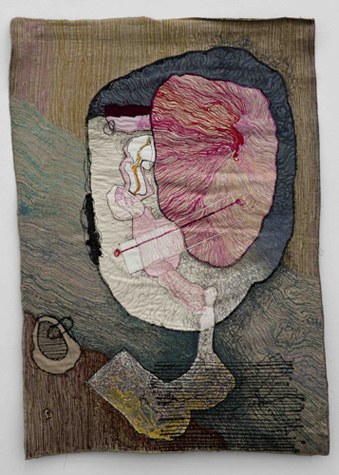

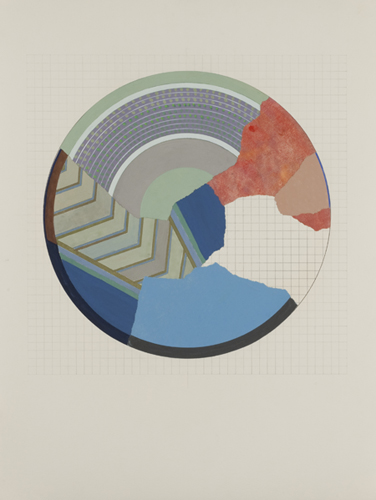

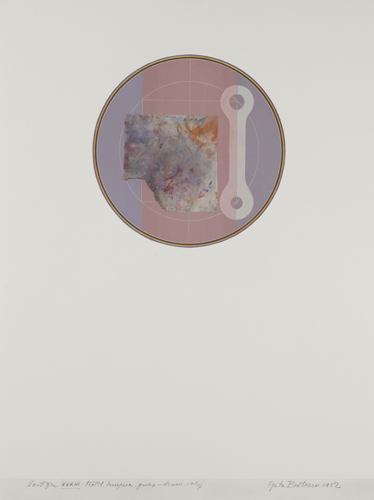

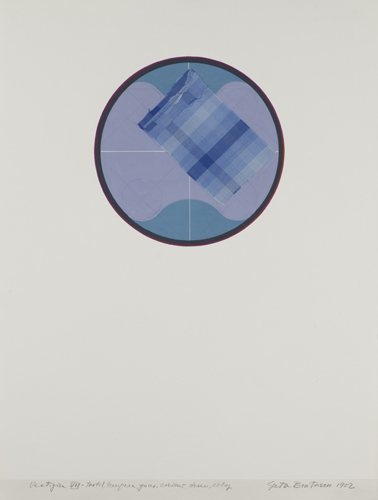

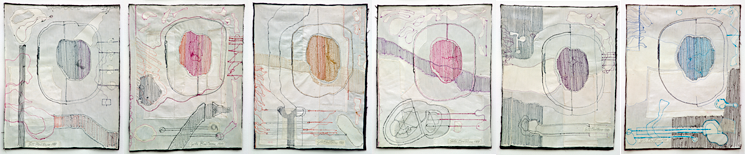

AO: Over the years you have made photographs and films, but in an episodic, discontinuous way rather than as part of a constant endeavor. Thefilms The Studio and The Hand of My Body date from 1977.  In the 1980s you were no longer working with film; it was the time of the “tightening of the screw” in Romania, when the careers of many Romanian artists underwent a change – sometimes a dramatic one – after the experimentalism of the ’70s. This change can also be seen as a process leading towards maturity. One can say that your work reached a stage of maturity, that it reached its full development. Major works, such as the series of “textile drawings” Medea’s Hypostases (1980); the series of textile collages Vestiges (1982) and the piece The Famous Vestige (1983); the collage series The Rule of the Circle, The Rule of the Game (1985), and the illustrations to Faust (1981-1982), sometimes continue themes that you started working with during the 1970s. They are, in a manner of speaking, concluding pieces in this thematic development. It would seem, therefore, that you resorted to “alternative” media – as they are sometimes called in Romania – only at particular junctures in your career, when the political pressure on the art world relaxed and an air of change and openness allowed for a more experimental art practice to take place. Drawing and collage, on the other hand, are almost always present in your work.

In the 1980s you were no longer working with film; it was the time of the “tightening of the screw” in Romania, when the careers of many Romanian artists underwent a change – sometimes a dramatic one – after the experimentalism of the ’70s. This change can also be seen as a process leading towards maturity. One can say that your work reached a stage of maturity, that it reached its full development. Major works, such as the series of “textile drawings” Medea’s Hypostases (1980); the series of textile collages Vestiges (1982) and the piece The Famous Vestige (1983); the collage series The Rule of the Circle, The Rule of the Game (1985), and the illustrations to Faust (1981-1982), sometimes continue themes that you started working with during the 1970s. They are, in a manner of speaking, concluding pieces in this thematic development. It would seem, therefore, that you resorted to “alternative” media – as they are sometimes called in Romania – only at particular junctures in your career, when the political pressure on the art world relaxed and an air of change and openness allowed for a more experimental art practice to take place. Drawing and collage, on the other hand, are almost always present in your work.

GB: You either draw or you make photography! For me, the line is the essence. Drawing is the foundation of my language. I draw with a pencil and I draw with scissors, with a pen, with anything. The collages I have been making lately are a kind of indirect drawing. It is the line alone that draws. I got these cards you see here on my studio table, and I collected ice cream sticks and these handles from shopping bags. I loved the cardboard and the sticks, so I drew with them.

AO: Still, you have been making collages, installations, films and photography in a country, where before 1989, the visual art world was dominated by old media, and above of all by painting. You didn’t work with painting, even though for several decades you worked in an artistic milieu dominated by it, one where painting was a mythologized medium. Today, they still say that “Romania is a country of painters.”

AO: Still, you have been making collages, installations, films and photography in a country, where before 1989, the visual art world was dominated by old media, and above of all by painting. You didn’t work with painting, even though for several decades you worked in an artistic milieu dominated by it, one where painting was a mythologized medium. Today, they still say that “Romania is a country of painters.”

GB: That is correct; painting has dominated in Romania, because painting is the most bourgeois artistic medium. Any communist representative would want to have a painting in his living room. It was the ruling class of Romanian society, its officialdom that nourished this pre-eminence and high importance given to painting.

AO: It’s not simply that you are not a painter; you do not paint at all.

GB: No, I don’t like to paint. Although drawing sometimes paints. I have works, collages that are painterly. Scissors draw. The objects are just objects, but you can do anything with them. I like that. Painting is the most elaborate medium; it is demanding, complicated. In addition, it has a great prestigious past. Were I to choose between Matisse’s paintings and his drawings, my preference is his drawings. But his paintings include drawing. Matisse was great at drawing. Impressionism, for example, has no attraction for me. I cannot do this kind of painting. I’ve seen an enormous amount of paintings; I’ve written quite frequently about painting; I can appreciate it, but it is not in my nature.

AO: You have made tapestry as well. Works such as Axia, Wind Instrumentalist, Three Planes, and Flying Figure, are from the early 1970s.

AO: You have made tapestry as well. Works such as Axia, Wind Instrumentalist, Three Planes, and Flying Figure, are from the early 1970s.

GB: Yes, I made tapestry, but I gave it up because it was too difficult; it’s too demanding. It also deteriorates easily, and is difficult to preserve. But I made the Medea series, which are textile works that I made myself. This is different. They have a reasonable size.

AO: Tapestry in Romanian contemporary art was also experiencing a renewal during the 1960s and ’70s. The same thing happened with sculpture, especially after the rediscovery of Constantin Brâncusi (who had been banned for two decades as a “cosmopolitan,” according to the socialist realist creed). But while Brâncusi’s legacy fostered the myth of the virile sculptor who dominates matter, tapestry was and still is seen in Romania as an art made by women, a minor undertaking, something that has more to do with craft, a “material” art. The critical reception of your Medea series, engraved or drawn by you in textile, was in this predominantly feminine key. The implicitly feminine irrationality in the Medea’s theme could be seen as being complicit with this pleasure of working with matter and with fragmented objects, the pleasure of touching, the meticulous assembling of pieces and fragments, which Romanian critics typified as feminized actions, even before 1989. In writing about these works in the text accompanying the exhibition The Artist’s Studio in Bucharest in 2012, the curator, Magda Radu, must have had all this in mind when she invoked the “bricolage principle” proposed by Catherine de Zegher. But while you talk in your texts about femininity, about Jung’s archetypal “mothers” who inspired your themes, you nevertheless firmly dissociate yourself from feminism.

GB: The pleasure comes naturally from my choice in this manner of working. I did write on occasion about femininity and feminism. These are two different things. Feminism is something else altogether; feminism is a uniform. I am for femininity.

GB: The pleasure comes naturally from my choice in this manner of working. I did write on occasion about femininity and feminism. These are two different things. Feminism is something else altogether; feminism is a uniform. I am for femininity.

AO: But doesn’t being associated with femininity bother you?

GB: Why would it bother me? No, tapestry is a technique like any other. I made textile collages. I love it even more than tapestry. They had a terrific success. They were in great demand from abroad. The textile scraps collected by my mother, and then by me in a small drawer, all this residual matter was of great use for me. I worked a lot with it.

AO: In the 1990s you worked with video, creating works such as Earthcake (1992), Automatic Cocktail and 2×5 (both from 1993). Earthcake seems to be a remake in a different tonality of the same theatrical feminine image as Medea was, ritualized and projected into the archaic.

GB: Earthcake was conceived as a ritual in its entirety — a filmed ritual. I made film and video with Alexandru Solomon and Ion Grigorescu.

AO: What is your medium of preference, the one you find most natural?

AO: What is your medium of preference, the one you find most natural?

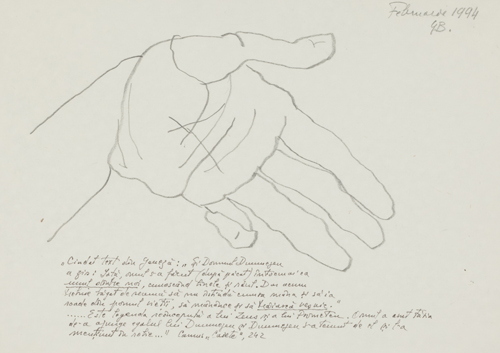

GB: The medium that feels most natural to me is drawing. The image, lithography, photography, film, they all are or contain drawing. When I made films and videos in which I played with my hands, I was seeing my hands as objects. I have lots of drawings with hands. I stopped drawing at some point, but afterwards I was afraid I had forgotten how to draw. The most difficult model to draw from is the hand. So I started drawing hands again as a test.

AO: Once you know how to draw, do you ever forget it?

GB: No, but I felt the need to submit myself to this test. Lately, I have been working with collage a lot, which is a kind of drawing with objects.

AO: Apart from the information you got by reading art magazines that found their way to Romania, or by visiting museums when travelling abroad, did you have occasion to see Western or Eastern European contemporary art before 1989?

GB: Yes, I saw a lot of contemporary art. Before 1989 I travelled to Russia, where I saw amazing collections of modern and contemporary French art. Later, in the ’90s, I travelled around Europe in a Fiat 1300 with my husband and saw quite a number of collections and museums.

AO: You have been compared with Louise Bourgeois in terms of artistic longevity, but also as a character. This may have to do with the fact that those who compared you were late in discovering you, as they were late in discovering Bourgeois.

GB: Have I been compared to Bourgeois? I am honored.

AO: Ciprian Mure?an’s artists book opens with a text written by you about Mure?an’s animation Un chien andalou. For someone like Lia Perjovschi you are an important artist. She once told me that she regretted not having met you before 1989.

GB: I am not familiar with the public history of art. I am not speaking about history as such, but what happened in Romania and in Romanian art in my lifetime. I spent a lot of time secluded in my studio. I had a family; I raised my boy. I had no time to go out with my colleagues. I was not immersed in the artistic milieu. This was my life. I would say it was good because it gave me time and quietude. I minded my own business. I didn’t join competitions.

AO: Has your perception of the West changed after the change of the political regime in Romania? You travelled during communism as well, but would you say that back then you had an idea of the West from the perspective of the East, and that this changed when political freedom was won in 1989?

GB: For me it did not change much. I enjoy seeing everything. I have albums and receive catalogues. I exhibit abroad. But my work is my work. These days the shopping bag handle inspires me, and I make some objects that take it as a starting point. This is what I have to do. And the curators who visit me are very knowledgeable. Nowadays there are no differences between us and them. In communist times I chose to stay here, I was not tempted to leave, and I think it was the right choice. It would have been impossible for me to start over abroad.

GB: For me it did not change much. I enjoy seeing everything. I have albums and receive catalogues. I exhibit abroad. But my work is my work. These days the shopping bag handle inspires me, and I make some objects that take it as a starting point. This is what I have to do. And the curators who visit me are very knowledgeable. Nowadays there are no differences between us and them. In communist times I chose to stay here, I was not tempted to leave, and I think it was the right choice. It would have been impossible for me to start over abroad.

AO: In 1999, you had a retrospective at the National Museum of Art in Bucharest, and in 2008 you received the National Award for Visual Arts. You are a valued and respected artist in Romania. However, you once expressed your disappointment that honors and recognition have left your work somewhat unknown and unstudied. And indeed, there are no monographic studies of your oeuvre as yet.

GB: Well, this is only half true. Things have their own way of evolving. Look at Bourgeois, who emerged late on the art scene.

AO: In 2004, you wrote that the wish to exhibit in the West was a closed chapter in your life. Then, in 2009, you wrote that you have experienced a major change on the surface of your life, and you were waiting to see how deep it would turn out to be. I suppose that in writing this you had in mind the international promotion of your work in recent years. In 2012, several works from your series The Rule of the Circle, The Rule of the Game were acquired by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Ion Grigorescu also now enjoys international recognition, but for him it started earlier.

GB: Many things have changed, society, relationships. This pleases me because it provides a new channel of communication, an intelligent one. What I try to do is keep my studio open for those who want to get to know me. But I have no hard feelings; this is not in my nature.

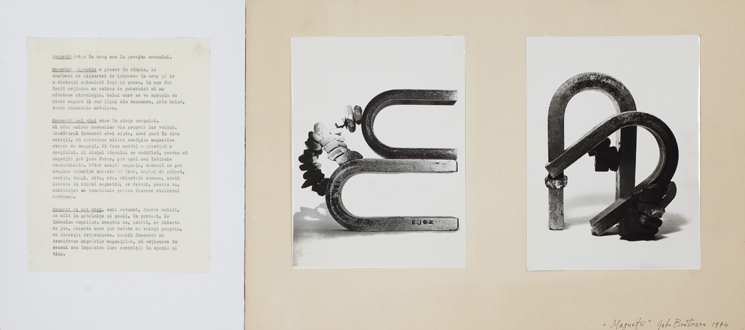

AO: In an interview on the history of Romanian photography with Mihai Oroveanu, former director of the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Bucharest, he stated that your photo-collage Magnets in the City (1974) was the first conceptual work in Romanian art.

GB: I love this work. It is very beautiful. I cannot be modest about it. It is an event, a singular work.

AO: Art professionals now speak about you as being a representative of East European conceptual art. Your place in Romanian art, as someone whose oeuvre distinguished itself from the trends, media, and techniques common in Romanian art before 1989, is already established. But this affiliation with Conceptualism is a novelty. True, it has been said that your work elicits a certain rationality, an intellectual dimension (as exemplified in your graphic works), stemming from your artistic training and from the fact that you authored books. But only recently has the connection between your works and Conceptualism been noted. It has a direct connection, it would seem, with significant changes that are taking place in Romanian contemporary art, and with its increased international recognition. This appears to have inspired efforts to evaluate and define conceptual practices in Romanian art, both current and historical, and to place them in the context of the neo-avant-garde. How do you feel about the label “Conceptualist”?

GB: Using a metaphor, I see these things exactly as a surgeon does while performing surgery. I cannot label my surgery. I work, that’s all.

AO: Do you recognize yourself as a Conceptualist?

GB: In a way, I do. My training points in this direction. I took courses in letters and philosophy; I read a lot. Camil Ressu, my master teacher, was a Conceptualist avant la lettre. His drawing was of an outstanding quality. To give you an example: one is tempted to draw the line of the neck as a continuous curve. However, Ressu would say: there are no hollows, there are only volumes. So this seemingly continuous neckline is actually made up of three different lines. This is a conceptualized expression of art. It is not in my nature to make decorative art. It does not work for me.

AO: Thank you.

Translation by Adriana Oprea and Anca Oroveanu.

Bucharest, April 2013

Adriana Oprea is a Romanian critic and art historian. She studies the history of Romanian art and art criticism after 1945, being currently involved in a PhD on the topic. Oprea also writes reviews and articles for various periodicals, and she is Associate editor for ARTA magazine, the main Romanian art publication and one of the few that is concerned with contemporary Romanian art. She collaborates with artists and writes texts for exhibition catalogues. Oprea is also an archivist at the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Bucharest. She lives and works in Bucharest.

Adriana Oprea is a Romanian critic and art historian. She studies the history of Romanian art and art criticism after 1945, being currently involved in a PhD on the topic. Oprea also writes reviews and articles for various periodicals, and she is Associate editor for ARTA magazine, the main Romanian art publication and one of the few that is concerned with contemporary Romanian art. She collaborates with artists and writes texts for exhibition catalogues. Oprea is also an archivist at the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Bucharest. She lives and works in Bucharest.