Interview with Elena Filipovic

Elena Filipovic is Senior Curator at WIELS Contemporary Art Centre, Brussels. ARTMargins Online spoke to Filipovic about her exhibition Alina Szapocznikow: Sculpture Undone, 1955–1972, which opened at WIELS Contemporary Art Centre in Brussels and traveled to the Hammer Museum, LA; MoMA, NY; and the Wexner Center for the Arts, OH.

Elena Filipovic is Senior Curator at WIELS Contemporary Art Centre, Brussels. ARTMargins Online spoke to Filipovic about her exhibition Alina Szapocznikow: Sculpture Undone, 1955–1972, which opened at WIELS Contemporary Art Centre in Brussels and traveled to the Hammer Museum, LA; MoMA, NY; and the Wexner Center for the Arts, OH.

ARTMargins Online: What prompted you to organize an Alina Szapocznikow retrospective when you did? What aspects of the artist’s work did you feel essential to reveal to Western audiences? What is the importance of Szapocznikow’s work at this particular historical, cultural moment?

Elena Filipovic: I had been following Alina Szapocznikow’s work for a few years, having at first only seen it in reproduction. Book reproductions hardly compare to the real thing but even in faded photographs some of the absolute singularity and strangeness of the work haunted me. I wondered how it could be that her work was not more visible, why I hadn’t encountered it in exhibitions before, and why—above all—I couldn’t find her anywhere in the narratives about the art of the 1960s and ’70s. Of course, all of these questions became even stronger once I had managed to see some pieces in the flesh. Moreover, much of her work appeared completely contemporary to me, engaged with the sort of visceral materiality and experimental impulse that I thought young artists were grappling with today, so it made perfect sense to try to stage her first big retrospective outside of Poland in a place dedicated to contemporary art.

Elena Filipovic is Senior Curator at WIELS Contemporary Art Centre, Brussels. She has curated a number of traveling retrospectives, including Marcel Duchamp: A Work that is not a Work “of Art” (2008-2009), Felix Gonzalez-Torres. Specific Objects without Specific Form (2010-2011), and Alina Szapocznikow: Sculpture Undone, 1955–1972, co-curated with Joanna Mytkowska (2011-2012), in addition to organizing solo exhibitions of artists such as Petrit Halilaj, Leigh Ledare, Klara Lidén, Lorna Macintyre, Melvin Moti, Tomo Savic-Gecan, and Tris Vonna-Michell. She was guest curator of the 14th Prix Fondation d’Entreprise Ricard, Paris (2012) and the Satellite Program at the Jeu de Paume, Paris (2010) and has, since 2007, been tutor of theory/exhibition history at De Appel postgraduate curatorial training program and advisor at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam. ARTMargins Online spoke to Filipovic about her exhibition Alina Szapocznikow: Sculpture Undone, 1955–1972, which opened at WIELS Contemporary Art Centre in Brussels and traveled to the Hammer Museum, LA; MoMA, NY; and the Wexner Center for the Arts, OH.

Elena Filipovic is Senior Curator at WIELS Contemporary Art Centre, Brussels. She has curated a number of traveling retrospectives, including Marcel Duchamp: A Work that is not a Work “of Art” (2008-2009), Felix Gonzalez-Torres. Specific Objects without Specific Form (2010-2011), and Alina Szapocznikow: Sculpture Undone, 1955–1972, co-curated with Joanna Mytkowska (2011-2012), in addition to organizing solo exhibitions of artists such as Petrit Halilaj, Leigh Ledare, Klara Lidén, Lorna Macintyre, Melvin Moti, Tomo Savic-Gecan, and Tris Vonna-Michell. She was guest curator of the 14th Prix Fondation d’Entreprise Ricard, Paris (2012) and the Satellite Program at the Jeu de Paume, Paris (2010) and has, since 2007, been tutor of theory/exhibition history at De Appel postgraduate curatorial training program and advisor at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam. ARTMargins Online spoke to Filipovic about her exhibition Alina Szapocznikow: Sculpture Undone, 1955–1972, which opened at WIELS Contemporary Art Centre in Brussels and traveled to the Hammer Museum, LA; MoMA, NY; and the Wexner Center for the Arts, OH.

ARTMargins Online: What prompted you to organize an Alina Szapocznikow retrospective when you did? What aspects of the artist’s work did you feel essential to reveal to Western audiences? What is the importance of Szapocznikow’s work at this particular historical, cultural moment?

Elena Filipovic: I had been following Alina Szapocznikow’s work for a few years, having at first only seen it in reproduction. Book reproductions hardly compare to the real thing but even in faded photographs some of the absolute singularity and strangeness of the work haunted me. I wondered how it could be that her work was not more visible, why I hadn’t encountered it in exhibitions before, and why—above all—I couldn’t find her anywhere in the narratives about the art of the 1960s and ’70s. Of course, all of these questions became even stronger once I had managed to see some pieces in the flesh. Moreover, much of her work appeared completely contemporary to me, engaged with the sort of visceral materiality and experimental impulse that I thought young artists were grappling with today, so it made perfect sense to try to stage her first big retrospective outside of Poland in a place dedicated to contemporary art.

I managed to convince my director at WIELS that this was something important to do, even if we weren’t a museum, even if we did not have a collection or the mandate to organize historic shows. I was in touch with Joanna Mytkowska, Director of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw and Marta Dziewańska, who works closely with her, as they were at that moment preparing a group show, Awkward Objects, in which Szapocznikow had a central place. The Warsaw museum was also in the process of digitalizing the entirety of the artist’s photographic archives, documents, and letters to make them available to the public, so it made sense to try to combine our shared interest in the artist and her team’s extensive knowledge of Szapocnikow. We co-curated the exhibition that nearly two years later became Alina Szapocznikow: Sculpture Undone, 1955-1972, concentrating on the moment that the artist inaugurated her own distinctive sculptural voice and on her most active and experimental later works. While it felt crucial to make the artist better known to a public that hadn’t gotten the chance to see her work before, we were very cautious about how this should be done. We felt we needed to find an alternative to the common tendency in Poland to read her work primarily in relation to her bodily suffering (her passage through several concentration camps, her life-long struggle with failing health, her painful and ultimately fatal battle with breast cancer). We did not want to deny that reality, but rather to insist on the primordiality of the work itself and its incredible formal, technical, and material experimentations, which needed to be considered without being overburdened by the circumstances that had so long attached themselves to the understanding of the work. We didn’t want people to continue to treat her with pity, especially as the artist herself never solicited it, but instead with the sort of exaltation that her work exudes.

I managed to convince my director at WIELS that this was something important to do, even if we weren’t a museum, even if we did not have a collection or the mandate to organize historic shows. I was in touch with Joanna Mytkowska, Director of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw and Marta Dziewańska, who works closely with her, as they were at that moment preparing a group show, Awkward Objects, in which Szapocznikow had a central place. The Warsaw museum was also in the process of digitalizing the entirety of the artist’s photographic archives, documents, and letters to make them available to the public, so it made sense to try to combine our shared interest in the artist and her team’s extensive knowledge of Szapocnikow. We co-curated the exhibition that nearly two years later became Alina Szapocznikow: Sculpture Undone, 1955-1972, concentrating on the moment that the artist inaugurated her own distinctive sculptural voice and on her most active and experimental later works. While it felt crucial to make the artist better known to a public that hadn’t gotten the chance to see her work before, we were very cautious about how this should be done. We felt we needed to find an alternative to the common tendency in Poland to read her work primarily in relation to her bodily suffering (her passage through several concentration camps, her life-long struggle with failing health, her painful and ultimately fatal battle with breast cancer). We did not want to deny that reality, but rather to insist on the primordiality of the work itself and its incredible formal, technical, and material experimentations, which needed to be considered without being overburdened by the circumstances that had so long attached themselves to the understanding of the work. We didn’t want people to continue to treat her with pity, especially as the artist herself never solicited it, but instead with the sort of exaltation that her work exudes.

AMO: Your Szapocznikow exhibition started at WIELS Contemporary Art Centre in Brussels and traveled to three venues in the United States (Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, Ohio). How did each venue guide your curatorial vision? For example, at the Hammer, the show seemed more focused on the artist’s biography in shaping the work’s very personal iconography, while the presentation at MoMA appeared to trace the work more formally and developmentally from holistic figures to fragmented body parts. Were you conscious of the way each institution would inform the work, and vice versa?

EF: Each of the four venues in which the work was shown has wildly different architectures, institutional histories, collections (or in the case of WIELS, no collection at all), and perhaps different audiences. Each of these factors wittingly or unwittingly shifted the show slightly. In each venue, Joanna and I had the privilege of working with incredibly talented curators who were passionate about Szapocznikow’s work and who brought their own knowledge and know-how to each presentation. At MoMA and the Hammer respectively, we worked closely with Connie Butler and Allegra Pesenti who were ideal partners for this project. I can’t say that we deliberately tried to shift the emphasis in one place versus another, but the institutional conditions and habits of each place opened up their own possibilities. At WIELS, we had the largest space at our disposal and, thus, the opportunity to show the most amount of works. Because of this luxury we could also feature extensive archival documents and photographs, which we displayed in a space separate from the exhibition space proper. This was a very conscious attempt to present Szapocznikow’s work and then to allow people to learn about her life and the historical context of the world around her, but not to impose one reading onto the other. In the later venues we had less space so while we privileged the work, we also let bits of the documentation of her life seep in.

EF: Each of the four venues in which the work was shown has wildly different architectures, institutional histories, collections (or in the case of WIELS, no collection at all), and perhaps different audiences. Each of these factors wittingly or unwittingly shifted the show slightly. In each venue, Joanna and I had the privilege of working with incredibly talented curators who were passionate about Szapocznikow’s work and who brought their own knowledge and know-how to each presentation. At MoMA and the Hammer respectively, we worked closely with Connie Butler and Allegra Pesenti who were ideal partners for this project. I can’t say that we deliberately tried to shift the emphasis in one place versus another, but the institutional conditions and habits of each place opened up their own possibilities. At WIELS, we had the largest space at our disposal and, thus, the opportunity to show the most amount of works. Because of this luxury we could also feature extensive archival documents and photographs, which we displayed in a space separate from the exhibition space proper. This was a very conscious attempt to present Szapocznikow’s work and then to allow people to learn about her life and the historical context of the world around her, but not to impose one reading onto the other. In the later venues we had less space so while we privileged the work, we also let bits of the documentation of her life seep in.

AMO: Again, this exhibition made connections between the objects on view and the artist’s personal history, both to her own bodily traumas and to the political events in Poland at the time. How would you contextualize her work within a larger history of Polish art — i.e., feminist and body art of the 1970s, and sculptors like Magdalena Abakanowicz? How would you contextualize Szapocznikow’s work within a broader history of sculpture and within movements such as Surrealism or Pop Art? For instance, one might draw parallels between her early sculptures to those of Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth, and later works to more contemporary artists like Kiki Smith. Were such references in your mind when you curated the show? Were they relevant in any way?

EF: Of course, when you look at Szapocnikow’s work you cannot help think of the broader history of sculpture, which she clearly knew about and self-consciously drew from, a history that goes from Socialist Realist influences in her monumental public sculptures to the distinct influences of Pop Art, Surrealism, the Duchampian readymade, and Nouveau Réalisme in her later work. It is interesting to trace the influences that she might have had but also to see the counter influences, the things that she seems to have positioned herself against. For instance, it is unimaginable that she was not aware of the rise of Minimalism and Conceptual art, especially through the contact that her graphic designer husband Roman Cie?lewicz, who was designing art magazines at the time that featured those works. Against the rigid geometries, cool authority, and industrial sheen of Minimalism, Szapocznikow’s gooey, amorphous, unpredictable forms made from poured polyurethane or serial repetitions of her body, cast in colored resins, offered a decisive counter to one of the most dominant forms operating at the time. And if you look at her series Photo-sculptures (1972), you cannot help call to mind the simultaneous rise of conceptual photography; but in Szapocznikow’s version, her photographs are inflected with as much of her body as her sculptures since each photographed specimen was a carefully chewed piece of gum, cast from the inside of her mouth. So yes, all of these influences and counter influences were definitely on our mind while curating the show and were part of the way we tried to help inscribe the artist into a larger history from which she had been painfully left out.

EF: Of course, when you look at Szapocnikow’s work you cannot help think of the broader history of sculpture, which she clearly knew about and self-consciously drew from, a history that goes from Socialist Realist influences in her monumental public sculptures to the distinct influences of Pop Art, Surrealism, the Duchampian readymade, and Nouveau Réalisme in her later work. It is interesting to trace the influences that she might have had but also to see the counter influences, the things that she seems to have positioned herself against. For instance, it is unimaginable that she was not aware of the rise of Minimalism and Conceptual art, especially through the contact that her graphic designer husband Roman Cie?lewicz, who was designing art magazines at the time that featured those works. Against the rigid geometries, cool authority, and industrial sheen of Minimalism, Szapocznikow’s gooey, amorphous, unpredictable forms made from poured polyurethane or serial repetitions of her body, cast in colored resins, offered a decisive counter to one of the most dominant forms operating at the time. And if you look at her series Photo-sculptures (1972), you cannot help call to mind the simultaneous rise of conceptual photography; but in Szapocznikow’s version, her photographs are inflected with as much of her body as her sculptures since each photographed specimen was a carefully chewed piece of gum, cast from the inside of her mouth. So yes, all of these influences and counter influences were definitely on our mind while curating the show and were part of the way we tried to help inscribe the artist into a larger history from which she had been painfully left out.

AMO: Szapocznikow’s work was introduced to American viewers and made visible in North America for the first time through a 2007 exhibition organized by Anke Kempkes at Broadway 1602 Gallery in New York. Did your exhibition build or expand upon this earlier show?

EF: The pioneering work that Anke Kempkes did through a series of exhibitions that included Szpacznikow, first at the Kunsthalle Basel and later at her gallery, was indeed important for having first introduced the artist’s work outside of Poland and for creating the international interest that eventually helped us to tour the exhibition. If no one had ever seen any of Szpacznikow’s work, there could never have been three major American institutions vying to take on our retrospective. There was, however, much more of her work still to make public and work to be done in relation to understanding the oeuvre, so research was begun to try to track down works that had long been considered lost and to examine the condition of works that had been stored in less than ideal conditions. Film footage of the artist’s studio taken just after her death was found. And the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw’s digitalization of the artist’s archive and organization of the first major conference on the artist were also elements that helped bring together new knowledge. All of these factors contributed to our reading and understanding of Szapocznikow’s work for the retrospective.

AMO: How does this exhibition relate to ongoing lines of inquiry that have persisted throughout your curating and writing projects? For example, how does Szapocznikow’s work connect to your interest in temporal works (such as David Hammons’) that transform or disappear over time, denying the claim to eternity traditionally granted to works of art destined for the museum?

EF: I am always surprised to find that just about every show I work on somehow connects to ideas and lines of inquiry inherent to nearly everything else I do. I usually don’t see the connections at first, which only later become apparent to me. Yes, formal instability and ephemerality interest me a lot and drive a number of projects I have done. And while I have written about or curated plenty of projects that involve perfectly conventional (heroic, stable, immutable) works, I tend to be particularly interested in things that seem to have fallen into the gaps (of the museum, of history, of perception). Maybe it’s Marcel Duchamp’s fault, since researching and thinking about him and his oeuvre has been my primary education.

EF: I am always surprised to find that just about every show I work on somehow connects to ideas and lines of inquiry inherent to nearly everything else I do. I usually don’t see the connections at first, which only later become apparent to me. Yes, formal instability and ephemerality interest me a lot and drive a number of projects I have done. And while I have written about or curated plenty of projects that involve perfectly conventional (heroic, stable, immutable) works, I tend to be particularly interested in things that seem to have fallen into the gaps (of the museum, of history, of perception). Maybe it’s Marcel Duchamp’s fault, since researching and thinking about him and his oeuvre has been my primary education.

AMO: How do you view this show in the context of your other curatorial work? You became well known with a retrospective of the work of Felix Gonzalez-Torres, in which you invited artists, acting as curators, to alter your original curatorial selection and scenography. That show appeared experimental in a way that was quite different from the Szapocznikow show – it seemed to question the very idea of a retrospective as a stable perspective on an artist’s work. How would you describe the experimental nature of the Szapocznikow show?

EF: As different as those two exhibitions you describe were in one sense, they were quite similar in another: each was an attempt to articulate an appropriate response to the oeuvre I was faced with curating. In the case of Felix Gonzalez-Torres,an artist whose entire oeuvre was arguably preoccupied with fragility, mutability, mortality and, fundamentally, the questioning of authority, it seemed vital to try to make these ideas affect the form of the exhibition itself. In other words, it would make little sense, I thought, to create a retrospective that would assert itself as a singular vision of stable, immutable authority (and I insist that this is really specific to Gonzalez-Torres). Instead I wanted to find a way to undermine those things by setting up a protocol such that in each of the three venues of the show, the exhibition I had curated got taken down half way through its duration and reinstalled by an artist who had been influenced in his or her own practice by Gonzalez-Torres. In each case, the artists I involved (Danh Vo, Carol Bove, and Tino Sehgal) selected an entirely different checklist of Gonzalez-Torres’s works, created another scenography, and responded to their own set of ideas about Gonzalez-Torres…) so in the end there was no “absolute” or “definitive” retrospective, only six exhibition versions that told six different stories about how to understand the artist. But however experimental or radical that may have sounded as a principle for a retrospective, it was, to my mind, simply the most fitting way to show Gonzalez-Torres’s oeuvre.

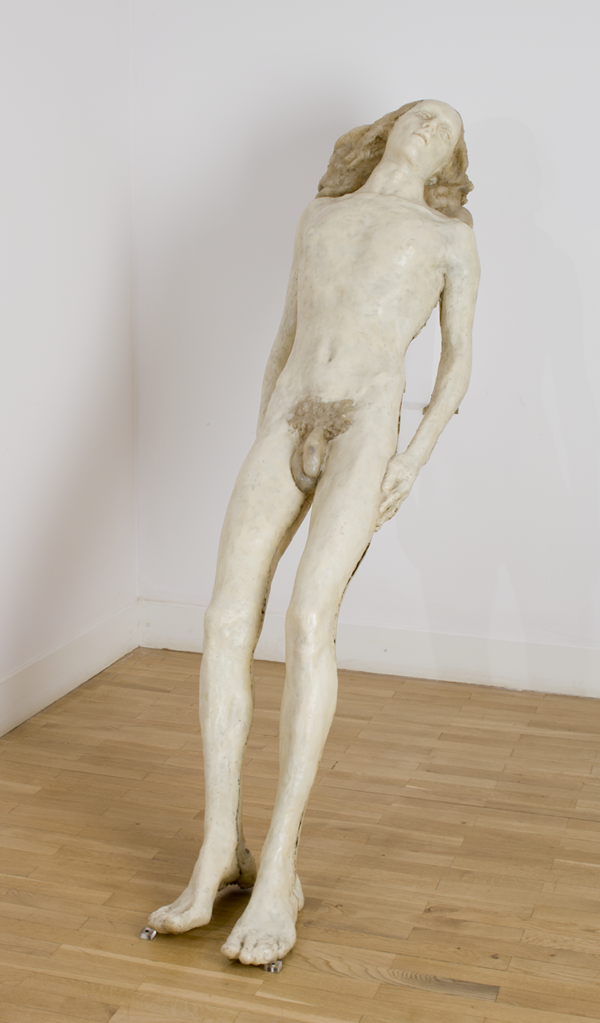

In Szapocznikow’s case, an artist who had never been shown widely outside of her native Poland, another kind of retrospective was required, one which allowed viewers to approach the work for, perhaps, the very first time. The particularity of the Sculpture Undone show instead was the way in each venue in which you saw it, you could “read” the development of the artist that went from her early more classical works (in which, nevertheless, a self-conscious bodily distortion appears) towards her pieces that become more and more experimental. At the heart of the show was the defiance of gravity, as a kind of leitmotif, which mirrored Szapocznikow’s own progressive concern with the precarious, unstable, and even ambiguously ecstatic body. The retrospective began with the classical bronze figures First Love (1954) and Difficult Age (1956), proud, defiant looking female nudes whose elongated necks already hint at the corporeal instability that would end with Piotr (1972), Szapocznikow’s last major work and arguably her most strange and revolutionary—a full body cast of her nude son made in such a way that his figure appears to be on the point of collapse or levitation, you cannot really tell which. Formally, Szapocznikow’s work is a lot kinkier and weirder than Gonzalez-Torres’s, and that was certainly palpable in the show we organized, but in order to allow that to be seen, there needed to be a certain rigor and classicism to the installation itself. That’s what I mean about the two retrospectives you cite, in fact, sharing something, despite their apparent or obvious differences. I think that as a curator, my responsibility is, perhaps, primarily to the work itself and to think alongside the artist (if they are alive) or without them (if they are dead) to try to find the most fitting articulation of form to honor the ideas of the oeuvre being presented. It’s tough work sometimes, but not a bad a job to have.

In Szapocznikow’s case, an artist who had never been shown widely outside of her native Poland, another kind of retrospective was required, one which allowed viewers to approach the work for, perhaps, the very first time. The particularity of the Sculpture Undone show instead was the way in each venue in which you saw it, you could “read” the development of the artist that went from her early more classical works (in which, nevertheless, a self-conscious bodily distortion appears) towards her pieces that become more and more experimental. At the heart of the show was the defiance of gravity, as a kind of leitmotif, which mirrored Szapocznikow’s own progressive concern with the precarious, unstable, and even ambiguously ecstatic body. The retrospective began with the classical bronze figures First Love (1954) and Difficult Age (1956), proud, defiant looking female nudes whose elongated necks already hint at the corporeal instability that would end with Piotr (1972), Szapocznikow’s last major work and arguably her most strange and revolutionary—a full body cast of her nude son made in such a way that his figure appears to be on the point of collapse or levitation, you cannot really tell which. Formally, Szapocznikow’s work is a lot kinkier and weirder than Gonzalez-Torres’s, and that was certainly palpable in the show we organized, but in order to allow that to be seen, there needed to be a certain rigor and classicism to the installation itself. That’s what I mean about the two retrospectives you cite, in fact, sharing something, despite their apparent or obvious differences. I think that as a curator, my responsibility is, perhaps, primarily to the work itself and to think alongside the artist (if they are alive) or without them (if they are dead) to try to find the most fitting articulation of form to honor the ideas of the oeuvre being presented. It’s tough work sometimes, but not a bad a job to have.

July 2013