Image Translation That Educates the Senses – The Hitchcock’s Paintings of Daniel Pitín

Futura (Projekt Room), Centre for Contemporary Art, Prague, April 4 – April 25, 2004

The recent work of the young Czech artist Daniel Pitín paradoxically re-establishes classical paintings as an important channel for contemporary media art. His painted scenes of the Hitchcock classic “The Birds” act as a critique and a celebration of the movie image and of electronic media.

The visual innovation that is often the focus of the new media art suddenly succumbs to the intricacies of a dialogue between the canvas and the film, between an old and a new medium.

Classical oil painting techniques, when used on a film scene, simultaneously sustain and destroy the tradition of representation both in film and in paintings. This leads to a mutual confrontation and translation between the images.

Pitín’s paintings are no longer a representation of the filmic image but an image translation that enriches the original visual experience of the painting as well as of the film. Painting becomes a type of a critique of the image and a representation that “educates” and emancipates our sense of sight.

The old and the new media reflect each other and decline to meet our expectations. This challenges us to commence an archeology of the image that identifies and associates visual experiences with different styles of “seeing.” We realize in these paintings that the styles of “seeing” are constructed and easily mistaken for natural.

Image translation

To make a photograph of a painting is a common documentary practice. The reverse approach, when the movie or the photograph is painted on the canvas, is documentary in a new way. It documents the genesis and the evolution of contemporary art itself as a practice of image translation that “educates” our senses.

Ever since the Impressionist era, photography and film have affected painting. Film inspired futurism and cubism to decompose the perspective and the movements of painting and to represent them simultaneously.

Human sight becomes a camera in paintings such as “Dynamism of a dog on a leash” by Giacomo Balla (1912) or Duchamp’s early “Nude Descending a Staircase” (1913). Painting in Modernism is a constant critique and experiment with the different forms of representation inspired by new techniques of seeing.

The influence of the movie and photography on paintings explains an important aspect of modernism, but in contemporary art we are witnessing an interesting reversal. There are attempts to see and interpret the movie, the photograph, and even the website through the means of a painting.

The saturation of the photographic and film image in the 20th century leads to experiments that try to surpass the new “naturalness” of the media images by something that is simply different.

The traditional techniques of painting bring this estrangement and difference when applied on the media images as their objects. Painting suddenly serves the functions ascribed to photography in the 19th century: it enables us to see in a new way the world saturated by media images that constitute the new “reality.”

This reversal in the relation between the painting and the new media is best seen in the case of the Francis Bacon and Gerhard Richter. Their relation to photography is diametrically opposed. The classical photography films by Eadweard Muybridge were a source of inspiration for Bacon’s motion studies and his attempt to create a different representation of the figure in painting.

Richter’s capitalist realism goes in the opposite direction, where painting interprets the new medium and helps us acquire distance from its force. Newspaper photography is the object, not a simple inspiration, in the series of blurry paintings about the German terrorist group known as the Baader-Meinhof gang. In these paintings, Richter tries to change our perception of the newspaper effect and the modern media handling of concrete events, not only to show a new visual effect.

Ever since the 60s and pop art, oil paintings have been an attempt to confront the dullness and the manipulation of the media, especially advertisement images. The strategy of image translations betweenthe paintings and the new media searches for a visual transgression, for new regimes and apparatuses of seeing and representation by becoming a critique of all previous regimes.

Such regimes and apparatuses are not only technical but also social and ideological constructs. When modern media is reflected on the canvas it emancipates and educates our senses to acknowledge these constructions.

Human sight is no longer natural; it is not even a camera, but a political ideology, technical and social construction that needs to be constantly challenged.

Painting Hitchcock

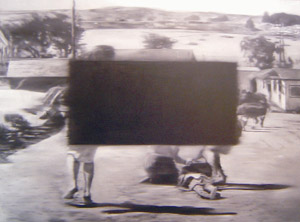

Daniel Pitín’s paintings use the movie “The Birds” by Alfred Hitchcock as a source of such confrontation and a search for a visual transgression. The scenes from the movie are painted on the canvas in a deranged and a blurred form. This alludes to the fast movements of the birds but also to possible problems with the film material.

|

The attacks of the birds acquire even more minatory impression because of this distortion of the movements that Pitín “realistically” paints.

We can even interpret it as a realistic painting of damaged tapes that creates a specific esthetics from the errors of the film medium.

The strange black square in the middle of the film scene with a group of schoolgirls and their teacher could be easily a mistake on the tape. It could also present an intention to hide their identity, or it is simply an ominous target that highlights the horror and fear.

Similar is the effect of the magnifying glass in the middle of the color canvas from the Hitchcock series that dramatically extends the time of the attack and the fear.

The mistakes and the imperfections of the film medium, the limits of one visual experience, are a new source of meaning and experience on the canvas because of the perverse realism. It educates our sight to realize the artifacts of the visual culture as not only constructed but even corrupted and unnatural in a strong sense.

The movie on the oil painting is actually an exercise in understanding the ideology behind every image. It is not a simple imitation of the film (hyperrealist painting) but it is not a pure construction of the image either (abstract painting). Between the mimesis and the anarchistic creation ex nihilo a new dimension emerges – the painting as a critique and an interpretation of all images and media.

The relation between the human eye and the camera on Pitín’s paintings remains tense, but at the same time fluid because of the redundancy of the image.

|

It is not, however, a typical post-modern game with reflection and self-reflection. The contact between the different media and apparatuses of seeing, between the film and the canvas, remains as sinister as the relation of birds and humans in Hitchcock’s movie.

It is a confrontation with something that is familiar and known but becomes foreign and deadly in one moment. The distorted film images on Pitín’s canvases and their translation through several layers (camera, eye, canvas) repeatedly point to this moment when something close and familiar becomes unnatural and frightening.

Hitchcock’s movies and Pitín’s paintings confront and complement each other. They teach our senses and reason to perceive and understand the image in its transformation. The dangerous liaison between the conservative technique of painting and the movie making radicalizes the relation between our “natural” sense of sight, the technical innovations and the artistic creation.

The movie and the paintings tell us a fear-provoking story about the relation between what is natural and unnatural, between seeing and thinking, experience and reason, between what is given and constructed.

The confrontation of media on these paintings can not be reduced to the movements of brush, the represented movements on the film or any real movements. The paintings, however, do not show the simple disappearance of the distinction between the real and the imitated.

|

More importantly, they explore the universal ability of everything to imitate and reflect on everything else. This does not lead to some infinite creativity or power of representations but promote the border cases – the mistakes and the limits.

It is the mistakes and the limits of the movie but also of nature and painting that are the object of interest. The limits force us not only to look at the image but to think about it, to translate between images, apparatuses and experiences, between thinking and seeing, technology and art in order to understand what is happening.

Pitín’s paintings represent the paradox of “thinking” the image as opposed to the common practice of imagining and representing a certain “thinking,” reason, or idea.

The translation of the images in his paintings reflects and summarizes the problem of contemporary art but also philosophy as a contraposition of reflection and experience, socially constructed and given, images and words, nature and technology that emerges in particularly frightening form in Pitín’s paintings.