Ilya Kabakov: The Soviet Toilet and the Palace of Utopias

This text was first published on the ARTMargins Online website on December 31, 1999. It is being republished in honor of its author Svetlana Boym (1959–2015), and Ilya Kabakov (1933–2023).

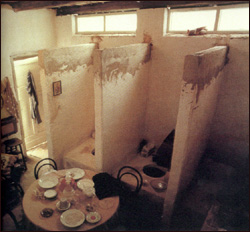

Ilya Kabakov, The Toilet, 1992.

At the end of the millennium, it has become fashionable to speak about the “end of history” and the “end of art,” to say nothing about the end of the world. Boris Groys has commented that Soviet civilization was the first modern civilization whose death we have witnessed, and there are more to come.(Boris Groys, “Un homme qui veut duper le temps” in Installations 1983-1995 (Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, 1995), pp. 17-19.) While the world might end, the art world does not have to. Arthur Danto suggests that we live in the era of the end of art, which is not at all bad for the artists.(Arthur C. Danto, After the End of Art (Princeton University Press, 1997). While not entirely agreeing with this utopia of artistic tolerance, Boris Groys believes that the museum would survive as an institution and determine the distinctions between art and non-art. (Groys’ conversation with Sven Spieker, “Boris Groys: The Logic of Collecting”, appeared in the journal ARTMargins (1999). I have also benefited greatly from reading Groys’ dialogues with Kabakov and from my own dialogues with Groys. See also Robert Storr, “An Interview with Ilya Kabakov” in Art in America [January 1995]).) It is simply the end of the Hegelian narrative of art history, which culminates in the self-reflexivity and diversity of art, liberated from a teleological master narrative. Kabakov’s work fits in well with the eschatological fashions of the end of the millennium. Yet it does not quite represent them. For Kabakov, art remains an inevitable, existential need and a therapy for survival. The artist loves the museum not merely as an institution, but as a personal refuge.

Kabakov has a strange sense of timing. His art works seem to come after the millenium, not right before it. Kabakov’s total installations look like the artist’s Noah’s arks, only we are never sure if the artist escaped from hell or from paradise . While conversant in the language of contemporary art, Kabakov’s projects tease the Western interpreter and evade “isms.” Is his art of homemaking modern, anti-modern, post-modern, or outmoded? On the one hand, it might appear that his art has little to do with modernism and post-modernism. In a way, the installations hark back to the origins of secular art and resemble an undecipherable baroque allegory. Or maybe they go back even further, to primitive creativity as a survivalist instinct – a way of fleeing from panic and fear, of hunting and gathering transient beauties in the wilderness of ordinary life. On the other hand, his project is belatedly modern,; it explores the sideroads of modernity, the aspirations of the little men and amateur artists and the ruins of modern utopias.

In the 1970s-1980s Ilya Kabakov was associated with the unofficial movement of Moscow “Romantic Conceptualism,” known also as NOMA. It was not so much an artistic school, but a subculture and a way of life.(Boris Groys coined the first name of the movement, Moscow Romantic Conceptualism. The artists Komar and Melamid, who were close to the movement and emigrated in 1979, called themselves “sots-artists.” The term NOMA was proposed by a younger conceptualist named Pavel Pepperstein, and was happily accepted by the artists who were involved with their individual projects and were not concerned with terminology. [. . . the artists who develop their individual projects and don’t mind any term.] The originalconceptualists were Andrei Monastyrsky, Eric Bulatov, Elena Elagina and Igor Makarevich, among others. For a discussion of NOMA see NOMA: Installation (Hamburger Kunsthalle Cantz, 1993).) In the time after Khrushchev’s thaw, the trials of Sinyavsky and Daniel, and the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, cultural life in the official publications and museums became more restricted. A group of artists, writers, and intellectuals created a kind of parallel existence in a gray zone, in a “stolen space” carved out between Soviet institutions. Stylistically, the work of the conceptualists was seen as a Soviet parallel to pop art, only instead of the advertisement culture they used the trivial and drab rituals of Soviet everyday life – too banal and insignificant to be recorded anywhere else, and made taboo not because of their potential political explosiveness, but because of their sheer ordinariness, their all-too-human scale. The conceptualists “quoted” both the Russian avant-garde and Socialist realism, as well as amateur crafts, “bad art,” and ordinary people’s collections of useless objects. Their artistic language consisted of Soviet symbols and emblems, as well as trivial, found objects, unoriginal quotes, slogans, and domestic trash. The word and the image collaborated in their work to create a rebus-like idiom of Soviet culture.(The artists of the last unofficial and occasionally underground Soviet group, the Moscow conceptualists, became known in the 1970s through a series of apartment art exhibits (called aptart), samizdat editions, and events, some of which resulted in direct confrontation with the Soviet police and arrests. (One of their outdoor exhibits was destroyed by bulldozers.) Kabakov, however, never engaged in explicit anti-government activities.)

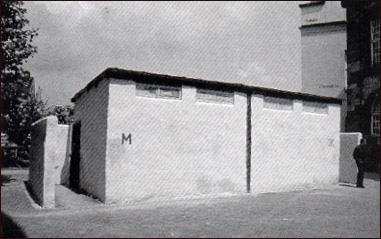

Ilya Kabakov, The Toilet, 1992. Exterior view.

Yet the situation of these artists was quite different. Kabakov observed that in Russia, since the nineteenth century, “art” played the role of religion, philosophy, and a guide to life. “We always dreamed of making the projects that would say everything about everything,” says the artist, laughing. “In the 1970s we lived like Robinsons, discovering the world through our art.” What was the hybrid metaphysical-epic novel in the nineteenth century became a conceptual installation in the 1970s. The conceptualists also continued the twentieth-century tradition of art-making as a lifestyle and a form of resistance, as in the artist communes of the 1920s (like the “flying ship,” the House of Arts which existed in Petrograd in 1918-1921), and as in the unofficial literary life of the 1930s, when the last surviving avant-garde group, OBERIU, engaged in the “domestic life of literature,” writing album poetry, putting on house performances, and reading poems to one’s best friends. The art of the conceptualists was fragmentary, but what made it significant was the context of kitchen conversations, discoveries, and dialogues in a private or semi-private, unofficial community. The conceptualists preferred collective action to written manifestoes, and did not mold themselves, like the avant-gardists, into small exclusive parties which frequently practiced excommunication. This was not a cult with a leader, but a group of eccentric individuals who partook in the same dangers of everyday life, shared a common conversation, and derived from it their sense of identity.

Now the artist has to carry with him his own memory museum and nostalgically reproduce it in each of his installations. If in the Soviet Union Kabakov’s work took the form of albums and fragmentary collections of Soviet found objects, in exile Kabakov embraced the genre of the “total installation.” Paradoxically, with the end of the Soviet Union, Ilya Kabakov’s work has become more unified and total. In it Kabakov documents many endangered species – from the household fly to the ordinary survivor, homo-sovieticus, from lost civilizations to modern utopias. What is the artist nostalgic for? How can one make a home through art at a time when the role of art in society dwindles dramatically? Is his work about a particular ethnography of memory or about global longing? What gives makes an installation “total” is not a unified interpretation, but the totality is the environment. The total installation turns into a refuge from exile. Kabakov describes being overcome by a feeling of utter fear during his first residence “in the West” when he realized that his work, taken out of the context, could become completely unreadable and meaningless, could disintegrate into chaos, or dissolve in the sheer overabundance of art objects. While acknowledging the connection to Western conceptual art, Kabakov insists on the existence of fundamental differences in the perception of artistic space in Russia and the West. In the West, conceptual art originated with a ready-made. What mattered was an individual artistic object sanctioned by the space of the Museum of Modern Art. In the absence of such an institution in the “East,” objects alone had no significance, whether they were drab or unique. It was the environment, the atmosphere, and the context that imbued them with meaning. What the artist missed most was the context of the kitchen conversation and the brotherhood of the NOMA artists, where all of his works made sense. Thus at the height of the information age, the artist tries to be a storyteller in the Benjaminian sense. He shares the warmth of experience, only his community is dispersed and exiled. So he shares his stories not with his own friends and compatriots, but with all those strangers nostalgic for lost human habitats and the slow pace of time.

Kabakov’s total installations have several features that concern the issues of authorship, narrative dramatization, space and time. In the total installation Kabakov is at once artist and curator, criminal litterer and trash collector, author and multivoiced ventriloquist, the “leader” of the ceremony and his “little people.” For a few years following the break up of the Soviet Union, Kabakov, who was already living abroad, persisted in calling himself a Soviet artist. This was an ironic self-definition. The end of the Soviet Union has put an end to the myth of the Soviet dissident artist. Sovietness, in this case, does not refer to politics, but to common culture. Kabakov embraces the idea of collective art. His installations offer an interactive narrative which could not exist without the viewer. Moreover, he turns himself into a kind of ideal communist collective, made up of his own embarrassed alter-egos – the characters from whose points of view he tells his many stories and to whom he ascribes their authorship. Among them are untalented artists, amateur collectors, and the “little men” of nineteenth-century Russian literature, Gogolian characters with a Kafkaesque shadow. Recently, Kabakov has discreetly dropped the adjective “Soviet” and now considers himself an artist, with two white space around the word.

While the artist builds his own total museum, changing walls, ceiling, floors, and lighting, the totality of the installation is always precarious; there is always something about to break or to leak, there is always something incomplete. And there is always an empty space, a white wall where artist and visitor can find their escape. Kabakov’s installations are never site-specific; they are, rather, about transient homes.(Ilya Kabakov, On the “Total Installation” (Cantz: 1992).) Kabakov writes that his total installations have more to do with narrative and the temporal arts than with plastic and spatial ones, like sculpture and painting. Kabakov insists that his installations are not based on a model of a picture, but on the world as a picture. In other words, the visitor “walks into” the installation and inhabits a picture which offers him a complete universe. The “fourth dimension” is providedby the texts. The temporal arts allow for many narrative potentialities. The installations incorporate other temporalities, and cheat linear time and the fast pace of contemporary life. Past and future have their specific places in the installation. The past is embodied in small objects, fragments, ruins, trash, and vessels of all sorts – chests of drawers, cupboards, rugs, and worn out clothes. Mechanisms and mechanical devices, usually dysfunctional and non-utilitarian by the time they appear in the installation, are also creatures of the past. The future is embodied in texts, frames, white walls and specially lit sheets of paper, and strange objects with cavities, cracks, and openings. There are no symbols here, nothing “personifies” time á la Dali. Time hides in the configurations of objects, in their special positioning – against an empty wall, on a pedestal, on the floor. As for the present, it remains a mystery in the making. Kabakov has compared his installations to a theater during intermission. They are about life caught unawares by the artist, and about the reenchantment of the world through art at any cost.(Ilya Kabakov, On the “Total Installation” (Cantz: 1992), p. 168.)

Ilya Kabakov, The Toilet, 1992. Men’s side.

The Toilets: Obscene Homes

The word “obscene” has an obscure etymology. It can be related to the Latin ob (on account of) plus caenum (pollution, dirt, filth, vulgarity). But it can also be related to ob (tension) plus scena (scene, space of communal ritual enactment, sacred space). In this sense, obscene doesn’t suggest anything vulgar, sexually explicit or dirty, but simply something eccentric, off-stage, unfashionable or anti-social. It is similar to profane (outside, but in proximity of the temple). The Toilet is Kabakov’s most obscene installation so far, responsible for a cultural scandal, but it is difficult to figure out what exactly is “off” about it. In 1992 Kabakov constructed an exact replica of provincial Soviet toilet – the kind that one encounters in bus and train stations – for the Documenta show in Kassel, Germany. The installation struck the visitors as at once affectionate and and repulsive, confessional and conceptual. It is after the execution of the toilets that Kabakov made the final decision not to return to Russia.

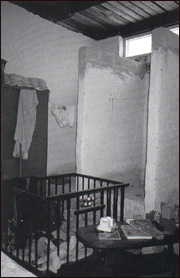

The toilets were placed behind the main building of the exhibition, Friedrizeanum, just the right place for such an establishment. Kabakov describes them as “sad structures with walls of white lime turned dirty and shabby, covered by obscene graffiti that one cannot look at without being overcome with nausea and despair.”(Ilya Kabakov, Installations 1983-1995 (Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, 1995), p. 162 and Ilya Kabakov, “The Toilet” (Kassel: Documenta IX, 1992). Special edition of the artist’s books, courtesy of Ilya and Emilia Kabakov.) The original toilets did not have stall doors. Everyone could see everyone else “answering the call of nature” in what in Russian was called “the eagle position,” perched over “the black hole.” Toilets were communal, as were ordinary people’s residences. Voyeurism became nearly obsolete; one developed, rather, the opposite tendency, that of retention of sight. One was less tempted to steal glances than to close one’s eyes. Every toilet-goer accepted the conditions of total visibility.

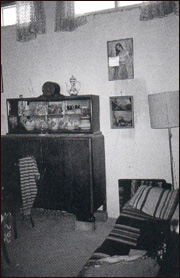

To go to the toilet, visitors had to stand in a long line. Expecting to find a functional place to take care of one’s bodily needs, or an artfully profane exhibit where one could flash a black outfit, visitors were inevitably surprised by the toilet’s interior design. Inside, there was an ordinary, Soviet two-room apartment inhabited by “some respectable and quiet people.” Here, side by side with the “black hole,” everydaylife continues uninterrupted. There is a table with a tablecloth, a glass cabinet, bookshelves, a sofa with a pillow, and even a reproduction of an anonymous Dutch painting, the ultimate in homey art. There is a sense of a captured presence, of an arrested moment: the dishes have not yet been cleared, a jacket has been dropped on a chair. Children’s toys frame the black hole of the toilet, which has lost its smell with the passage of time. Everything is proper here, nothing appears obscene.

The toilet, of course, is an important stopping point for the discussion of Russia and the West. Travelers to Russia and Eastern Europe, from the Enlightenment to our day, have commented on the changing quality of personal hygiene as a marker of the stage of the civilizing process. The “threshold of civilization” was often defined by the quality of toilets. Perestroika started, in many cases, with perestroika of public and private toilets. Even Prince Charles pledged to donate a public toilet to the Pushkin Institute in Petersburg. In the major cities, paid toilets decorated by American advertisements and Chinese pin-up girls replaced public toilets like the ones reproduced by Kabakov, and the new rich prided themselves on their “europrepairs,” which included toilet and bath. In the cultural imagination, the toilet stands right on the border between public and private, Russia and the West, sacred and profane, high and low culture.

Ilya Kabakov, The Toilet, 1992. Women’s side.

Kabakov leaves his toilet at the crossroads of conflicting interpretations. Should the installation be taken literally or interpreted as a metaphor – of vanished Soviet life, of itsÄ’4¡ery or affectionate resilience? Or maybe it is a psychoanalytic metaphor of maternal space? Kabakov tells two tales, relating the two points of the project’s origin: the autobiographical and the art-historical. Both are told in the voice of a wistful storyteller who shares his secrets with a kind stranger on a long train journey, with whom he develops a deep but transient intimacy. The first tale is about the artist’s and his mother’s many stories of inner exile within the Soviet Union, and the early loss of a place called home.

The childhood memories date back to the time when I was accepted to the boarding school for art in Moscow and my mother decided to abandon her work [in Dniepropetrovsk] to be near me and to participate in my life at school…She became a laundry cleaner at school. But without an apartment [for that one needed special resident permits] the only place she had was the room where she arranged the laundry – tablecloths, drapes, pillowcases – which was in the old toilets. Of course, they were not dirty toilets, but typical toilets of the old boy school which were transformed into laundry boards. My mother was chased out by the school mistress but unable to rent even a small corner in the city. She once stayed there illegally for a night, in this tiny room practically in the toilets. Then she managed to find a folding bed and she stayed there for a while until a cleaning lady or a teacher informed on her to the director…My mother felt homeless and defenseless vis-avis the authorities, while, on the other hand, she was so tidy and meticulous that her honesty and persistence allowed her to survive in the most improbable place. My child psyche was traumatized by the fact that my mother and I never had a corner to ourselves.(Ibid., pp. 162-163. Translation mine.) In contrast with this affectionate memory of past humiliation, the tale of the project’s conception is a tongue-in-cheek story of a poor Russian artist summoned to the sanctuary of the Western artistic establishment, the “Dokumenta show,” much to his embarrassment and humiliation: “With my usual nervousness I had the impression that I had been invited to see the Queen who decides the fate of the arts. For the artist this is a kind of Olympic Game…The poor soul of a Russian impostor was in agony in front of these legitimate representatives of great contemporary art…Finding myself in this terrifying state, on the verge of suicide, I distanced myself from those great men, approached the window and looked out…”Mama, help” – I begged in silence. It was like during the war…At last, my mother spoke to me from the other world and made me look through the window into the yard- and there I saw the toilets. Immediately the whole conception of the project was in front of my eyes. I was saved.”(Ibid., p. 163. Then Kabakov proceeds to argue with Dante Alighieri that it is not love that inspires art but fear and panic.)

The two origins of the toilet project are linked – the mother’s embarrassment is reenacted by her artist son, who feels like an impostor, an illegal alien in the home of the Western contemporary art establishment. The toilet becomes the artist’s diasporic home, an island of Sovietness, with its insuppressible nostalgic smell that persists even in the most sanitized Western museum. Yet the museum space is not completely alien to the artist; it is a space where he can defamiliarize his humiliating experience. Panic and embarrassment are redeemed through humor.

Another origin of Kabakov’s toilet is to be found in the Western Avant-Garde tradition. There is a clear “toiletic intertextuality” between this project and Marcel Duchamp’s “The Fountain” (La Fontaine). Duchamp purchased a mass produced porcelain urinary, placed it on a pedestal, signed the object with the pseudonym R. MUTT, and proposed to exhibit at the American Society for Independent Artists. The hang jury rejected the project, saying that while the urinary is a useful object, it is “by no definition, a work of art.” In twentieth-century art history this rejection has been seen as the birth of conceptual art and of an artistic revolution, which happened to take place in 1917, a few months before the Russian Revolution. Subsequently, the original “intimate” urinary splashed with the artist’s signature has vanished under mysterious circumstances. What survived was the artistic photograph by Alfred Stieglitz made from the “lost original,” which has added an aura of uniqueness to a radical avant-garde gesture. A contemporary wrote that the urinary looked “like anything from a Madonna to a Buddha.” In 1964 Duchamp himself made an etching from Stieglitz’s photograph and signed it with his own name. The permutations of the best known toilet in art history perform a series of defamiliarizations, both of the mass-reproduced everyday object and of the concept of art itself, and challenge the cult of the artistic genius. Yet, paradoxically, by the end of the twentieth century, we witness an aesthetic reappropriation of Duchamp’s ready-mades. Duchamp’s artistic cult imbued everything he touched with an artistic aura, securing him a unique place in the modern museum.(For an insightful discussion of Duchamp see Dalia Judovitz, Unpacking Duchamp: Art in Transit (University of California Press: Berkeley and London, 1996), pp. 124-135.)

In comparison with Kabakov’s toilet, Duchamp’s urinary really does look like a fountain; it is very clean, “Western,” and individualistic. Besides, scatological profanity itself became a kind of avant-garde convention – part of early twentieth-century culture as represented by Bataille, Leiris, etc. Kabakov’s installation is not merely about radical defamiliarization and recontextualization, but also, more strikingly, about inhabiting the most uninhabitable space – in this case, the toilet. Instead of Duchamp’s sculpture-like ready-made, we have here an intimate environment that invites walking through, storytelling, and touching. (The visitors are usually allowed to touch objects in Kabakov’s installations.) The artist’s own artistic touch is visible throughout. Kabakov took great care in arranging the objects in the inhabited rooms around the toilet, those metonymical memory-triggers of Soviet everyday life.

Duchamp questioned the relationship between high art and the mass reproduced object, and played with the boundaries of the museum. Yet he took the survival of the museum for granted, as well as the role of art and artists in society. In Kabakov’s work, one gets a sense of the fragility of any artistic institution. The artist’s installation is a surrogate museum, as well as a surrogate home. In his ready-mades Duchamp was concerned with the context and the aura of the object, but not so much with its temporality. Kabakov works with the aura of the installation as such, and with the drama of captured, or constipated, time. It is this temporal and narrative excess of the old-fashioned toilet that makes it new and nostalgic at the same time.

In the Russian press, Kabakov was reviewed very negatively. In spite of the political differences among his reviewers, they all seemed to agree that the toilets were an insult to the Russian people and to Russian national pride. Many reviewers evoked a curious Russian proverb: “Do not take your trash out of your hut” (ne vynosi sor iz izby), meaning do not criticize your own people in front of strangers and foreigners. The proverb dates back to an ancient peasant custom of sweeping trash into a corner behind a bench, and burying it inside instead of taking it outside. There was a common superstition that evil people could use your trash for casting magic spells.(Vladimir Dal’, Tolkovyi slovar’ zhivogo velikorusskogo iazyka (St. Petersburg, 1882), Vol. IV, p. 275.) This is a peculiar superstition against metonymic memory, especially when exhibited in an ambiguous foreign context. Kabakov’s evocative domestic trash of the Soviet era was regarded by the Russian reviewers as a profanation of Russia.(It is hard to imagine Duchamp’s urinary being interpreted as an insult to French culture, in spite of its provocative title “La fontaine.” On the other hand, the insults that Kabakov endured [received] are part of being a “Soviet artist” – a role that Kabakov chose for himself not without inner irony and nostalgic sadomasochism.)

The artist shunned this symbolic interpretation. He recreated his toilets with such meticulousness – working personally on every crack on the window, every splash of paint, every stain – that the inhabited toilet turned into an evocative memory theater, irreducible to univocal symbolism. Russian critics expropriated the artist’s toilets and reconstructed them as symbols of national shame. National mythology had no place for ironic nostalgia.

In the “West,” as Kabakov observed, there was also a curious tendency to see the toilet as a representation of Russia, only this time, a literal one. The ethnographic “other” is not supposed to be complex, ambivalent, and similar to oneself. The museum guard in Kassel told the artist how much he liked the exhibit and asked him what percentage of the Russian population lived in toilets after perestroika. The guard was actually right on the mark. Kabakov teases his viewer with almost ethnographic literalism. His art does not follow the modernist prescription of examining material and medium as such, nor does it employ the postmodern device of placing everything in quotation marks. The objects have an aura not because of their artistic status, but because of their awkward materiality, outmodedness, and otherworldliness – not in any metaphysical sense, but merely in the sense of being fragments of a vanished (Soviet) civilization.

Kabakov is an archeologist and a collector of banal memorabilia. The black hole of the toilet is surrounded by found objects from the Soviet children’s world. This appears to be an inverse framing: objects frame the black hole, but the black hole gives them their uncanny allure. When another passionate collector of modern memorabilia, Walter Benjamin, visited Moscow in 1927 he abstained from direct ideological metaphors and theoretical conclusions, and instead offered a detailed and seemingly literal description of everyday things. In a letter from Moscow he wrote, “factuality is already theory.” In other words, a narrative collage of material objects tells an allegory of Soviet reality. The same principle is at work in Kabakov’s installations, where objects are on the verge of becoming allegories, but never symbols. There is an excess of narrativity, or narrative potentiality in Kabakov’s installations. They intrigue the visitor with their mystery, like detective stories, and offer many controversial clues. Where indeed are the hosts of the toilet-duplex? What made them leave in a rush without even clearing the table or washing the dishes, as “nice, orderly people” would do? Are they standing in line for toilet paper? Was it fear of invasion, or of a strange encounter with aliens or natives? Has it already happened or is it immanent? What kinds of skeletons are we about to discover in the closet?

Kabakov’s installations offer the visitor objects to touch and stories to explore, leaving her alone in the role of an amateur detective, memoirist, or allegorist. There is one striking similarity between Kabakov’s installations and the actual toilet: both should be visited in solitude. The visitor finds herself stranded in the toilet; there are so many things to see, to read, and to touch here. She feels a little guilty lingering in this obscene, yet strangely human space – like the communal apartment neighbor who has occupied the communal toilet for too long, caught up in daydreaming and reading foreign magazines. It seems that any moment the other neighbors are about to come knocking, threatening to break the precarious solitude, to violate this moment of stolen pleasure.

Kabakov’s toilet is not about the “shit of the artist” – to name another conceptual ready-made by Mario Metz – nor is it even about the metaphysical shit of Milan Kundera or Georges Bataille. It is not really pornographic; in fact, there are some clothes left on the chair, but there are no unclothed people. Yet the perverse toilet-goer cannot stop herself from a far-fetching exploration of the invisible shit. In the choice of subject matter, Kabakov clearly appealed to scatological sensationalism as well as to Russian and Soviet exoticism, even if in the end he does not “deliver.” One is reminded that the success of another émigré, Vladimir Nabokov, was related to Lolita’s scandalous topic. Nabokov insisted that the novel was not pornographic, because pornography resides in the banal and repetitive structures of narrative, not in the subject of representation. Similarly, Kabakov’s toilet does not offer us the conventional satisfaction of a single narrative, but leaves us at a loss in a maze of narrative potentials and tactile evocations. What makes it obscene is its excessive humanness and humor.

Yet what is obscene in Kabakov is neither the vulgar nor the sexual, but rather the ordinary, the all too human. “There is a taboo on humanness in contemporary art,” Kabakov said in one of our conversations, sounding a bit like a disgruntled Russian writer of the nineteenth century, complaining about the coldness of the West. At the same time, one is struck by this insight. Humanness is not really a subject of contemporary art, which prefers body, ideology, or technology to the outmodedness of affect. Roland Barthes has observed the paradoxical nature of contemporary obscenity. He says that in high culture sentimentality has become more obscene than transgressive; the story of affections, frustrations, and sympathies is more obscene than Georges Bataille’s shocking tale of the “pope sodimizing the turkey”: “Sentimentality and surprise have become outmoded even in the lover’s discourse. [..] As a (modern) divinity, History is repressive, History forbids us to be out of time. Of the past we tolerate only the ruin, the monument, kitsch, what is amusing; we reduce this past to no more than its signature. The lover’s sentiment is old-fashioned, but this antiquation cannot even be recuperated as a spectacle.”(Roland Barthes, A Lover’s Discourse, pp. 177-178. See Svetlana Boym, “Obscenity of Theory,” Yale Journal of Criticism, Vol. 4, No. 2, 1991, pp. 105-128.) Kabakov’s nostalgic obscenity does not simply refer back in time, but rather sideways. In his artistic quest, Kabakov moves away from the much explored verticality of high and low toward the horizontality of the banal and its many invisible dimensions.

The toilet is embarrassing, not shocking. It does not contain the excrement of the artist, but his emotion. The toiletic black hole does not allow the artist to rebuild the perfect home of the past; leaving an unbridgeable gap in the archeology of memory. The black hole of the toilet is the opposite of Malevich’s avant-garde icon, the “black square,” which Kabakov loves to hate. The black hole of the toilet might be equally mystical, but its power lies on the border between art and life. The toilet becomes one of the artist’s diasporic homes, a home away from home, a home in the museum , which “off-stages” the predictable narrative of Russian and Soviet shame and Western experimental eschatology.

Kabakov’s work is about the selectivity of memory. His fragmented “total installations” become a cautious reminder of gaps, compromises, embarrassments, and black holes in the foundation of any utopian and nostalgic edifice. Ambiguous nostalgic longing is linked to the individual experience of history. Through the combination of empathy and estrangement, ironic nostalgia invites us to reflect on the ethics of remembering.

In my view, Kabakov’s success in the West is not due to his recreation of Russian and Soviet exotica for foreigners, but to his ability to commemorate and transcend it. It is not the specific details of the lost home and homeland that matter, but the experience of longing. Kabakov’s distracted Western viewers all share that intimate and haunting longing that often overwhelms them in the middle of a crowded museum, but most of them have too little time to figure out what exactly they are longing for.

Kabakov’s work is about the selectivity of memory. His fragmented “total installations” become a cautious reminder of gaps, compromises, embarrassments, and black holes in the foundation of any utopian and nostalgic edifice. Ambiguous nostalgic longing is linked to the individual experience of history. Through the combination of empathy and estrangement, ironic nostalgia invites us to reflect on the ethics of remembering.

In my view, Kabakov’s success in the West is not due to his recreation of Russian and Soviet exotica for foreigners, but to his ability to commemorate and transcend it. It is not the specific details of the lost home and homeland that matter, but the experience of longing. Kabakov’s distracted Western viewers all share that intimate and haunting longing that often overwhelms them in the middle of a crowded museum, but most of them have too little time to figure out what exactly they are longing for.