Re/Opening the DAAD Archives

IF THE BERLIN WIND BLOWS MY FLAG: ART AND INTERNATIONALISM BEFORE THE FALL OF THE BERLIN WALL AT DAADGALERIE, N.B.K., AND GALERIE IM KÖRNERPARK, SEPTEMBER 9, 2023 – JANUARY 14, 2024

The exact aim of the large-scale, three-site exhibition, When the Berlin Wind Blows My Flag: Art and Internationalism Before the Fall of the Berlin Wall, is difficult to define. The first sentence of the exhibition’s introductory text promised to offer insight “into the history of the DAAD Artists-in-Berlin Program (Berliner Künstlerprogramm—BKP)” and through that “the art scene in West Berlin before the Wall came down.” Based on this promise, one might have expected a systematic historical approach. However, the curators, Melanie Roumiguière, currently the Head of Visual Arts at DAAD BKP, and Nóra Lukács, doctoral candidate of Humboldt University in Berlin, conducted an asystemic subjective selection of archival moments to nuance the prestigious German institution’s history. The exhibition presented a selection of original artworks from Berlin public collections, interspersed with documents, including records of decision-making processes, correspondence, publications and newspaper clippings from the DAAD BKP archives. The displays were perplexing and crowded, with hundreds of documents on display, not only engaging but also testing the audience’s attention. Many of the issues highlighted, supported by archival documents, may have tempted the viewer to interpret them as examples that illustrate systemic problems supporting consequent institutional critique. However, the exhibition did not go into the context of determining the significance and weight of these cases in the operational history of the BKP or the West Berlin scene.

As “one of the world’s most respected artist-in-residence programs,” as they describe themselves on the website, the DAAD BKP Fellowship needs no lengthy introduction. The BKP, established in 1963, was funded by the Ford Foundation from the United States and the Berlin Senate. According to the founders’ official communication, the program aimed to prevent the claimed “cultural isolation” of post-WWII West Berlin, under American occupation at the time, and separated from the rest of West Germany. They programmatically invited artists from all over the world, primarily North American and Western European artists, and secondarily artists from South America, East Asia, and the satellite states of the Soviet Union. In 1965, keeping the original approach, the West German Federal Foreign Office took over the residence program, integrating it into the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD). DAAD is the joint organization of German universities and student bodies created to foster their international relations, founded in 1925. The DAAD BKP subsection has specific literature, music and visual arts departments inviting creators for a one-year residence in West Berlin. The Berlin Wind exhibition exclusively focused on the visual arts department from the 1963 foundation to the fall of the Berlin Wall. During this period, the DAAD BKP hosted over 230 international artists.

In the daadgalerie, the exhibition opened with an explanation of the political agenda of the foundation project of the DAAD BKP, while taking detours to make diverse political remarks on the program’s history. The second and most extensive section, in the n.b.k. (Neue Berliner Kunstverein/New Berlin Art Association), gathered narrative elements of the artist’s memories, works and archived documentation around the different forms of isolation. The Galerie im Körnerpark magnified the singular controversy surrounding Hungarian-American artist Agnes Denes’s BKP fellowship.

The daadgalerie exhibition introduced the launch of the residency and its aims and operation in the context of the then-contemporary Berlin scene. The BKP did not directly reveal their agenda, yet the curators opened the exhibition by displaying the direct American hegemonic expansionist aims of the Ford Foundation. They showed how the BKP tried to gain international relevance by promoting artists they found to be artistically advocating for the “correct” Western cultural episteme. Materialized in the valorization of non-figurative abstract paintings—for example by Wojciech Fangor, Georges Rickey, Emilio Vedova—in the bipolar Cold War world, this cultural clash between West and East was deemed to be the epithet of Western Art. The exhibition also highlighted the conflict that artificially injected foreign money into the Berlin cultural scene and thus disturbed its balance. Giving large amounts of money and exhibition opportunities to foreign artists with a well-defined artistic approach led to dissatisfaction in the local scene.

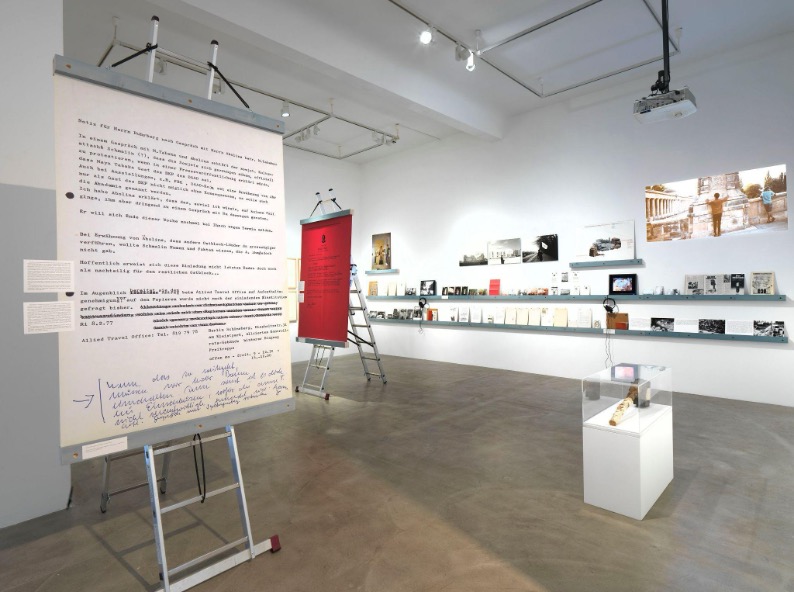

Installation view with the works of the C. & Center for Unfinished Business, Wojciech Fangor, Georges Rickey, Emilio Vedova. If the Berlin Wind Blows My Flag, daadgalerie. Photo: Jens Ziehe.

It would have been crucial to interpret the West Berlin phenomenon within the broader West German context regarding the strong presence of American culture and artists in state and commercial institutions in the historical geopolitical complexity. After the post-Holocaust moral death of European culture, in the efforts to revitalize German culture per se—similar to other fields of public interest of the 1950s and 1960s—the dominant figures of the German art scenes found the art and artistic trends of the United States were an example to follow or a way forward. However, this approach conflicted with the interest of German cultural actors, especially the younger generations. The local scene complained, most of all, that all public funds and institutions, fairs and other representative events, such as documenta in Kassel, were strongly dominated by American art. In contrast, there was hardly any exhibition space left for emerging German artists. The West Berlin scene’s standoffishness and criticism of the American presence, cultural dominance, and expansion were not unique geographically or to DAAD’s program. Addressing this aspect seems indispensable if we want to say something about the cultural turmoil in the former German capital, a key conflict zone of the Cold War.

The daadgalerie exhibition also provided insight into the internal workings of the BKP. Institutional history and archiving processes are generally discussed along the lines of institutional profiles and decision-makers. However, more attention has recently been paid to those invisible employees of institutions and archives whose work is essential for operational tasks. Sonya Schönberger’s contemporary reflection paid homage to the DAAD BKP’s staff member, Barbara Richter, who worked for the program for over twenty five years, doing major care work, keeping in touch with the fellows, and later organizing events and publications. Juxtaposing her legacy and the institutional archive, the displayed mountains of personal letters sent to Richter by artists demonstrated the importance of her as a figure. This sentimental moment was counterbalanced with Luiza Prado’s commissioned piece on the institutional involvement of Werner Haftmann, recently exposed as a former SS member and war criminal. Haftmann was director of the Neue Nationalgalerie during this period, and in this capacity, he was a regular member of the BKP selection committee until 1974. However, what influence Haftmann’s previous military commitments had on his decisions in his DAAD advisory statutes was generously left to the visitor’s imagination.

Installation view: If the Berlin Wind Blows My Flag, n.b.k. Photo: Jens Ziehe.

In contrast to the daadgalerie, the n.b.k. site focused on the artists, their work and their networks. Parallel micro-histories unfolded through original works, related art documentation, artbooks, catalogs, and approximately 150 pages of typewritten documents. In an almost cynical twist on the Ford Foundation’s original argument for action, the curators took a more personal approach, focusing on institutional isolation and its impact on artistic practice. The exhibition displayed works created during the fellowship that—as the curators claim—were largely ignored by the BKP leadership at the time due to their direct political relevance.

One section put a strong emphasis on the personal isolation of artists. During the fellowship year, many artists experienced loneliness and cultural alienation, which left marks on the works produced during their stay in Berlin. Some turned to self-assessment in the expatriate context, like Dorothy Iannone or Maria Lassnig, while others drew attention to marginalized social groups, such as guest workers co-existing with mainstream Berlin society.

In another section, the curators thematized acclaimed institutional inequality and exclusion: while the BKP usually organized exhibitions for American and Western artists in the city’s top cultural venues, fewer opportunities were offered to fellows from the Eastern Bloc. Lacking exhibition space, these artists occasionally realized their work elsewhere, bringing their artistic dialogue into the public space. One such example is the work of Endre Tót—a Hungarian artist who emigrated to West Germany after his BKP scholarship ended—entitled TÓTalJOYS, in which he exhibited or performed his textual works in German public spaces. Among them was the documentation of the street performance I Am Glad If The Berlin Wind Blows My Flag, which gave the exhibition its title. Tót went on the streets of Berlin with his flag showcasing the text.

Endre Tót, Berlin TÓTalJOYS, West Berlin, 1979. Photo: Herta Paraschin.

The profiles of the artists featured in the n.b.k. also demonstrated how the Cold War bipolar world, the intersection of East and West, and the DAAD scholarship enabled some Eastern Bloc artists to reside in the West. In keeping with the political agenda, in particular, artists from the Eastern Bloc whose art was judged by the jury as anti-establishment and Westernized were invited. However, while in the previous thematic sections, the curators reconstructed the meta-structures of organic institutional and personal isolation, here, they dismantled the Iron Curtain’s ideological premise of ultimate political isolation. One section of the exhibition included a cross-section of the cultural transfer between East and West Berlin, focused on Jürgen Schweinebraden’s private EP Galerie in East Berlin. Schweinebraden contacted and even exhibited BKP fellows, for instance Robert Filliou, Charles Simonds, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Roman Opałka and Stephen Willats. An exciting inclusion was the American Charles Simonds’s letter describing the culture shock experienced when visiting the EP Galerie. Simonds was surprised to report that East Germany had a vibrant cultural life and contacts with the West.

Installation view of the section about Schweinebraden’s EP Galerie. If the Berlin Wind Blows My Flag, n.b.k., Photo: Jens Ziehe.

The closing piece in the exhibition space was a 60-minute video by American artist Shelley Silver, Former East/Former West. In 1994, she asked the people on the street about basic but, at that time, shifting political concepts in the context of German reunification, such as: What is democracy? What is the difference between West and East Germans? From the responses, we get a sharp picture of the notion of citizenship and the political and cultural inclusion and exclusion dictated by the Western hegemonic episteme. Although the video is about German reunification, the clear divisions between first and second-class citizenship, cultural and historical experience provide an opportunity to transfer what was said in the video to the broader context of the Eastern Bloc or even the rest of the world in relation to the hegemonic Western centers.

The somewhat detached but particularly interesting interlude was Agnes Denes’s Early Works, on display at Galerie im Körnerpark. Apart from being the first Denes solo show in Germany since 1978, the sub-exhibition was an interesting case of how an institution’s communication could deviate from historical evidence. Even though the exhibited works were from the BKP Archive—courtesy of the artist—documents revealed that Denes received but did not take up and complete her fellowship in Berlin, as the institution could not budget her required working conditions. She is not the only invited artist who did not take up the opportunity, but she is the only one who is, regardless, listed as a DAAD BKP fellow. Moreover, Denes’s 1978 solo exhibition, which was self-organized in the America House in Berlin, is solely credited to the BKP on their website to this day.

Denes is still, despite this revelation, listed as a BKP fellow on the archival website, although the first line of her biography now states that the artist did not take up the grant. As this seemed to contradict what was stated in the Körnerpark exhibition, I contacted one of the curators, who told me that the first sentence of the biography had recently been amended. The biography of Denes, written by Eva Scharrer a few years back, had been edited, without an editor’s note, and only partially. In the second half of the text, it was left in that the BKP organized Denes’ 1978 Berlin exhibition. So what happened then? Although the curators provided evidence to support their claim that Denes was not a fellow, the institution retains her name on the fellow’s list. Moreover, they used the unmarked amendment to obscure, metastasize and attempt to deny the fiasco of the institution’s history, while further perpetuating false narratives.

Installation view, Agnes Denes: Early Works, If the Berlin Wind Blows My Flag, Galerie im Körnerpark. Photo: Nihad Nino Pusija.

This issue brings us to the ultimate question: what was the aim of this project beyond the multifocal semi-historical systemic narration? As the curators created the three-site exhibition with ongoing public funding and institutional support through the BKP, in the final reflection, I will consider these exhibitions as they relate to the profile of the institution of DAAD BKP. The fact that a particular entity examined an old phase in its own history and its hypothetical setbacks is something to be valued. However, while dissecting the first thirty years of the BKP fellowship’s historical operations and revisiting the canonization of its profile is undoubtedly fascinating, the question rightly arises: what exactly happened then and since?

Installation view with works from Dorothy Iannonem: If the Berlin Wind Blows My Flag, n.b.k., Photo: Jens Ziehe.

The issue of institutional continuity was not considered in any way. In fact, in an exciting maneuver, a retrospective false bridge was formed in the name of implied reflective self-criticism. In addition to the archival works, the curators invited alumni fellows and young contemporary artists to create new works for the exhibition and offered the institutional archive as artistic material for commissions. In the attitudes of the younger generation and the curators, there was a return to the theoretical trending keywords of today, such as race-centric postcolonialism and contemporary feminist attitudes, without reflecting on the then-contemporary cultural, political and in general epistemic realities. We are witnessing a kind of ahistorical institutional woke-washing mechanism, which in turn aims at a symbolic dismantling of continuity.

But is today’s BKP different from twenty, forty or even sixty years ago? Are the current decision-making processes more inclusive? Are they autonomous? Who decides? Based on what? Is its communication more thoughtful, or is it as protectionist as before? Is it even reasonable to expect an institution not to be protectionist? Perhaps not, but to correct past mistakes in the light of self-legitimated content is to be expected.

In sum, even without the broader historical accuracy, the pragmatic evidence provided in the exhibition obscured any forms of institutional action it may have aspired to, and maintained the perceptions of the professional and broader public that often derive from the canonized profile of the DAAD BKP. If the Berlin Wind Blows My Flag raised relevant questions that reach well beyond the scope of the implied institutional history or critique. It touched on relevant discursive issues such as the still prevalent legacy of the Cold War era in the consolidation of a rigid cultural hierarchy between the East and the West, or rather between the West and the rest. Through the history of an institution that still stands today, the exhibition made the case for cultural diplomacy and soft political advocacy’s effect on the assertion of sovereign art.