“I Follow the Work Into the Rabbit Hole.” An Interview with Maria Loboda

Maria Loboda is a Berlin-based visual artist who works interdisciplinarily, creating installations that combine objects, linguistic elements, plants, audio recordings, illustrations, drawings and photographs. She was invited to participate in the 58th International Art Exhibition of Venice Biennale, curated by Ralph Rugoff, with three works created in 2017. In the Arsenale, Loboda’s shows the multimedia installation Lord of Abandoned Success (L’Argile Humide). In the Central Pavilion in the Giardini, two digital prints from the on-going series Zero Dynasty – Zero Dynasty II and V are being shown, and in the Bookshop Pavilion Stirling, her work Young Warrior in the Landscape Watching the Birds Go By (Pastoral) is being displayed.

Karolina Majewska-Güde: Is your source material generated organically, depending on the project, or have you developed a consistent methodology with its own stages and rituals?

Maria Loboda: It usually starts with words, with a title, a poem, out-of-context terminology, a chemical compound description… Anything which I consider to inhabit a certain quality to be a “verbal sculpture.” If it functions on this lingual or written level, I feel stimulated to attempt to transform it into a dimensional object, or even an entire exhibition. My titles are very important for me, they act like spells and are often the key to the works.

I like the idea that words can have so many different material incarnations, and the objects for me are the vessels into which I can pour the narration. I don’t like to repeat myself by using the same materials, I am trying almost always to touch new ground, maybe also for the simple fact that I like to amuse myself whilst making art. I like to dive into new worlds and meet artisans and technicians who can help me develop my thoughts. To create exhibitions in different countries, and keep them always as site specific as possible, corresponds to an urge to satisfy my need for adventures. I never work in a studio, I like to be in transit, I like to take long walks in cities, and develop ideas in my mind. I can spend days walking up and down department stores, libraries museums, gardens, busy flower, fish, or textile markets. And afterwards I sit down wherever I happen to be living at the moment, at a hotel or an apartment, and I start to think and bring it all together, staying alone for several days.

I write everything down, I am travelling with my favourite few books, some trinkets, and my notebooks, and I take photos. I think a lot of artist do it the same way, nothing out of ordinary here. I work well in transit, I am usually the calmest when waiting for planes or trains. One is everywhere and nowhere at the same time.

KMG: Is there any hierarchy in the themes that attract you? Do you use art to investigate specific areas of life?

ML: Sure. I am trying to understand why humans create myths, why they lie, why they conceal their feelings, why they create riddles. I want to understand the psychology behind repression, desire, longings, fear, envy (“why did Greta Garbo seclude herself?”), among others. And I want to cherish the philosophical concepts that are out there, the theories that the human brain came out with centuries before our own existence. And I particularly like the ones that were proven wrong, the misfit ideas, but also the ones that proved their worth.

KMG: You often explore the effects of confusion and strangeness. Things seem to be different from what they are, though you remain in control of the game. Is is this your way of dealing with the issue of knowledge and power?

ML: I love to observe, to delve more and more deeply into a hidden story. No closed doors, and no hedges have ever stopped me. I was never afraid to steal, or to do a break-in to gain more knowledge, or to follow my work into a rabbit hole. Even though I never really broke into a gallery or museum, I would I guess that if my desire to find out something was strong enough, I would do it. Yes, there is certainly knowledge and power, but I always hide in plain sight. I like art viewers who are like hunters: you have to be a bit obsessed and cheeky, and when you have this in you, and the work is good enough, then no knowledge is outside of your reach. It’s the quality of the art work, the quality of the concept behind it that has to have enough power to make you long for it. And it’s ultimately one’s own decision whether to dissect a work of art, or whether to let it tempt and taunt you from afar. I prefer the second. And I prefer artists and beholders who know that sometimes one has to cheat the rules of the game, not to win, but to understand and to amuse oneself.

KMG: I think about your works like open constellations of heterogenic fragments; you create sets of new relations between elements. Is this a fair description of your work?

ML: To me they are like bouquets of thoughts. A good flower bouquet does not consist of all of the same flowers. You mix fine roses with other plants and then you bind them together with a lace. It’s difficult to explain empirically how I combine the elements in my works. One has to create works that function on a sacred level as if it was profane. The elements have to be able to evoke desire in the beholder. Since I am reluctant to explain my works academically, here is a little something that formed my way of artistic thinking from my early years as an art student, from the Comte de Lautréamont’s Les Chants de Maldoror: “Beautiful as the Chance Meeting on a Dissecting Table of a Sewing Machine and an Umbrella!”

KMG: What is the function of living things (trees, for instance) in your works?

ML: The cyprus trees in This Work is Dedicated to an Emperor were born from an effort to create public sculptures that are already embedded in the environment. I wanted to use something that exists around us naturally, something one does not pay too much attention to. I tend to slightly corrupt the living elements I use, leaving intact their natural beauty. The flower bouquet may be pretty, but it’s also an insult (as in my work A guide to Insult and Misanthropy), and the lush tree branches on the ceiling represent all the “predatory” qualities of nature. I find the strong human drive to cultivate nature interesting, our hubristic belief that nature is sending sacred messages to us humans in the form of clouds, smoke, flights of birds etc., as in those religions that view nature as a goddess. And there’s a brutal dichotomy: nature is colossally disinterested in mankind.

KMG: What is the story behind the works that you are showing at this year’s Biennale?

Maria Loboda. Zero Dynasty II, 2017. Digital print on Hahnemühle cotton paper. Image courtesy of Maisterravalbuena Gallery.

ML: All my works in the Venice Biennale were existing works from former solo shows, and chosen as such by Ralph Rugoff. I am glad I wasn’t faced with the responsibility of creating new works. The Lord of Abandoned Success and Zero Dynasty were originally shown at IAC Villeurbanne in 2017, during a solo show (curated by Magalie Meunier) titled La Fête, la Musique, la Noce. There, both works, the wet clay sculptures (The Lord of Abandoned Success) and the photographs (Zero Dynasty), were exhibited the same room of the gallery. The exhibition was resembled the inside of a temple. With Lord of Abandoned Success I wanted to create this classic artistic situation, forming abstractions out of lumps of clay. But then I decided to abandon these lumps, wrap them in bankers’ attire, in finest cotton shirts. And I left the whole thing all wet and dripping, as if I was almost ready to continue but then never resumed the task. The title … is a Tarot Card the Eight of Cups. I have always loved this interpretation. I wrote it down many years ago and waited until I would find a good sculptural form for it. Before Villeurbanne I tried it out in another solo show at the Power Plant in Toronto.

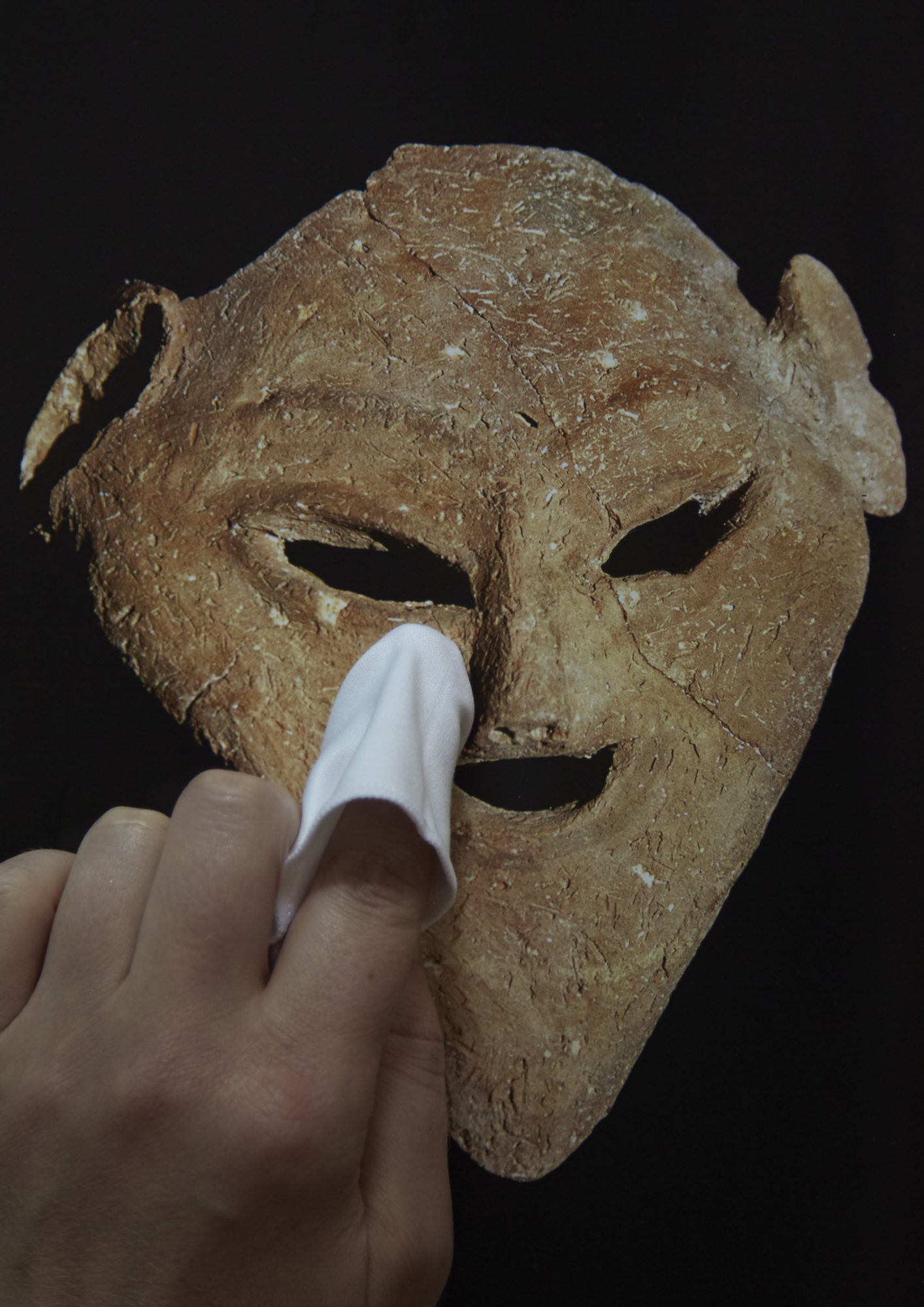

KMG: What is going on in the photographs that are part of Zero Dynasty?

ML: The artefacts that I am cleaning in these photographs come from a catalogue about the Egyptian Zero Dynasty, the dynasty that preceded everything. The dusk and the dawn of human endeavours. Zero Dynasty started out as a commission for an art magazine called Starship few years ago. A friend once told me that human civilization survives only because of the skill and tenderness of restorers and archaeologists. I am intrigued by the tenderness of restoration.

KMG: And what about your intervention in the bookshop pavilion with your work Young Warrior in the Landscape Watching the Birds Go By (Pastoral)?How does this piece reflect on the ways space operates?

ML: It was the decision of the curator, and I liked it. As you can imagine, sometimes the positioning of works in exhibitions of a scale such as the Venice Biennale, where so many, many works need to find their space, – is very pragmatic. Luckily, Ralph offered me the bookshop amongst four other options.

KMG: Thank you.

This interview was conducted over email on August 1, 2019.

Articles in this special issue:

[su_menu name=”Venice Biennale”]