How Do We Remember the Past?

How Do We Remember the Past? Czechoslovak Socialist Realism, 1948 – 1958. Rudolfinum Gallery, Prague, November 7, 2002 – February 9, 2003

November 7 still carries some unpleasant connotations for all those who lived in the countries of the former East Bloc before 1989. On November 7, we used to celebrate the anniversary of the Great October Revolution; it was a date that – with many others – reminded us of a bitter reality, that the country in which we lived was occupied by the Soviet Army, and that freedom of speech was far beyond our reach.

November 7 still carries some unpleasant connotations for all those who lived in the countries of the former East Bloc before 1989. On November 7, we used to celebrate the anniversary of the Great October Revolution; it was a date that – with many others – reminded us of a bitter reality, that the country in which we lived was occupied by the Soviet Army, and that freedom of speech was far beyond our reach.

Symbolically, on November 7, 2002, 85 years after the historical shot from the ship Aurora that started the Bolshevik revolution, the Rudolfinum Gallery in Prague opened a show entitled Czechoslovak Socialist Realism, 1948 – 1958. This is the first survey of Czech and Slovak fine arts from the decade following the Communist coup in 1948, the period dominated by the dictate of the unprecedented political and cultural link between Prague and Moscow and the cult of Josef V. Stalin.

Curated by Tereza Petišková, the exhibition is thematically divided into five parts – landscapes, portraits, images depicting constructions of socialist architecture, ritualization of life, and life of the army; All of which was done in respect to the architectural layout of the Rudolfinum Gallery, a neo-renaissance building from the late-19th century located on the right bank of the Vltava river.

In two rooms on the ground floor of the gallery, we find a special appendix to the show, a collection of memorabilia, and gifts to the first two post-war Communist leaders: the first “working class president”, Klement Gottwald, and his follower Antonin Zapotocky.

While the only pre-1989 official artistic platform, the Union of Czechoslovak Fine Artists, regularly organized monstrous and expensive exhibitions of its members that praised and promoted the Communist Party ideology, the exhibition in Rudolfinum is the first post-1989 curatorial attempt to gather paintings, sculptures, and, marginally, also drawings produced by the artists of “sorela” (as socialist realism is nicknamed by the local art historians).

It was also the first to challenge both their artistic quality and their role in post-war Czechoslovak culture and society. Needless to say, propaganda art that served the regime and especially the production from the 1950s, the time of the most horrendous and brutal acts against the “enemies” of socialism (including executions) appeared on the black list after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Not a single art historian has touched it as material for “serious” research. As fast as the streets of Czech cities were renamed, and public monuments of Lenin, Marx, Gottwald and other Communist “potentates” were removed or destroyed after November 1989, art historians wanted to forget the nightmare of “sorela” that swept away not only artists working in different styles, but that, paradoxically, threw over the board many inter-war left-wing intellectuals.

Modernism was a taboo – the prominent protagonists of socialist cultural politics called it “the symptom of the past liberal and monopoly capitalist era”,(Ideologicky program Dohody ceskych vytvarnych umelcu-realistu [Ideological Program of the Agreement of Czech Fine Artists-Realists], in: Skutecnost I., no. 1, 1946, pp. 15 – 16; reprinted in: Ceske umeni 1938 – 1989: Programy, kriticke texty, dokumenty [Czech Art 1938 – 1989: Programs, Critical Texts, Documents], Jiri Sevcik et al. (eds). Prague: Academia 2001, p. 94.) and any suggestion of art production from behind the Iron Curtain was censored.

Face to face with the exhibition of Czechoslovak Socialist Realism, the fundamental question for any art historian who deals with the 20th century is how to cope with art that is a direct and clear reflection of totalitarian power and ideology, as well as what kind of criteria should be applied to such production.

In other words, it is important to ask “to what extent has the morality (or ethics in general) of artists played a role in establishing socialist realism” as the only “true” expression of life under socialism, as the editor of the Czech architectural magazine, Architect, put it in the recent questionnaire addressed to a number of art historians and critics.

I believe it is crucial to see the phenomenon of socialist realism not only with regard to ethical and civic responsibility, but also with respect to the social and artistic development in East Central Europe in the 1920s and 30s. Undoubtedly, ideological battles inside of the Czech inter-war avant-garde had an impact on post-1948 art; and although it might seem absurd at first sight to compare experimental avant-garde production with the conservatism and academic style of “sorela”, many avant-garde artists and thinkers (let us take for consideration the theories of Karel Teige or Jiri Kroha, among others)(Compare, for instance, with the recently published book, Karel Teige, 1900 – 1951: L’Enfant Terrible of the Czech Avant-Garde, Eric Dluhosh – Rostislav Svacha (eds.). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press 1999. See also Jiri Kroha.) have prepared the ideological “ground” for the official art of the 1950s. From today’s perspective, this art needs to be seen as a condemnable compromise.

However, the paradox is, as I already pointed out above, that the post-war Communist elite annihilated the avant-garde as an oppositional theory and practice. At the same time it was capable of extracting from avant-garde utopian ideals something viable and vital that attracted (and manipulated) the masses.

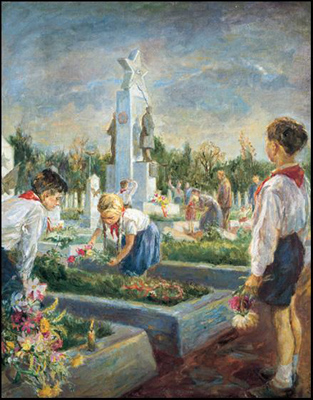

One of the paintings displayed in the Rudolfinum Gallery depicts a group of Czech pioneers laying down fresh flowers on the gravestones of Soviet soldiers. Entitled “They Remember”, this 1954 painting shows a piety of young boys and girls whose life in peace was redeemed through death of Red Army heroes. Their memory is shaped by gratitude and their identity is rooted in devotion to the Big Brother.

And yet, the title of this mediocre and pathetic painting could be taken as an appeal to any art historian because it provokes a basic but very essential question: How do we remember earlier times and uncompleted, unreflected pasts that continue to haunt the present? In other words, how do we remember and cope with a history that we want to forget?

There can be no doubt that the period of socialist realism belongs to the haunting “specters” of art history, and any researcher or curator who addresses its ups and downs should approach it as a socio-cultural and political phenomenon rather than a purely formal or aesthetic category. It is just this aspect of the Czechoslovak Socialist Realism show that makes it a highly problematic and ideologically misleading project.

It is bothersome to see lack of the social, historical, and interdisciplinary contextualization of the works on display that make the visitors either appreciate the brush strokes or walk around the show and sarcastically joke about the naivete and foolishness of the artists.

While seeing the exhibition myself, I immediately noticed both these reactions of other visitors. Neither connoisseurship nor irony can help to critically comprehend the complicated network of ideological, artistic, and psychological relations that were involved in Stalinist propaganda.

Moreover, the interiors of Rudolfinum Gallery – late 19th century decorative interiors with stuccos, colored walls, high ceiling, sky lights – endow the “sorela” pieces an aura that elevates superficial, often formally poor, and ideologically unconvincing art genres on the pedestal of aesthetically enjoyable art.

Additional programs for both professionals and the general public – workshops, conferences, screenings, city walks, concerts(For more details on the public programs related with the exhibition Czechoslovak Socialist Realism, 1948 – 1958, please see the website of the Rudolfinum Gallery in Prague: www.rudolfinum.cz.) – only partially substitute, at least in my opinion, the absence of a critical context of the show. Although wall texts often overwhelm viewers with unnecessarily didactic connotations, they could work very well in the case of this display.

If one considers that today’s Czech teenagers do not identify with the victims of Communist repressions, and vaguely know about what happened in 1948 and 1968,(See the recent survey commissioned by Czech daily, Lidove noviny, published on Friday, January 9, 2003.) and that a deep nostalgia for “old good days” of Communism flourishes among older Czech citizens or in the regions with high unemployment, the lack of such framework is not only a residue of a highly formalist reading of art that accompanied most of the 20th century art history. More importantly, it also contributes to the amnesia with which, I believe, Eastern Europe will continue to be a place of a mythic and deeply unreflected identity.