Hidden Holocaust

Elhallgatott Holocaust/Hidden Holocaust, March 18 – May 30, 2004, Mucsarnok, Budapest

The Mucsarnok (or Kunsthalle) is a major exhibition space for contemporary art in Budapest and its region. This March 18 through May 30, it was also the site of the Elhallgatott Holocaust/Hidden Holocaust exhibition. To mark the sixtieth anniversary of the deportations from Hungary to Auschwitz, no fewer than two other Holocaust related exhibitions also appeared. At the Galeria Centralis, Auschwitz: Reconstruction, Representation, Remembrance, and at The House of Terror, Iniquity.(Galleria Centralis is supported by the Open Society Institute of the Soros Foundation and Terror House (Terror Haz) is a controversial Museum supported by the Hungarian government.)

After leaving Elhallgatott Holocaust I feel overwhelmed. The exhibition raises many emotions and questions. It propels me sufficiently to begin writing (and here it is three months later). It contains a large body of work from numerous genres and eras.

Some pieces are historical and others specifically created for the exhibition. Restrictions of space do not allow me to devote sufficient comment on much of the work presented. Therefore, my purpose shifts to a discussion not only of specific artistic practices but also the curatorial process particularly in an area that is thematically loaded.

Rising to the surface, like muck on a newly mowed lawn, these exhibitions affirm, disturb or reconfigure narratives which permeate the most diverse sectors of the Hungarian social fabric.(In Auschwitz we see how the links were blatantly manipulated. On display is a deconstruction of two exhibitions from 1965 and 1979 that were located at Auschwitz and sponsored by the Hungarian government. In both examples, historians reconfigured the Holocaust narrative: in the earlier case Jews and other victims were omitted entirely and replaced by a collective anti-fascist victim; in the ’79 exhibit Jews and Roma were re-inserted into the narrative. In the Iniquity exhibition, focusing on children, the caption on the poster states that the exhibit is about the 1.5 million European and 190,000 Hungarian children who perished in the Holocaust. We can infer that some of these children were Jewish by the fact that the poster contains a well-known image of a young boy with a yellow star on his jacket.)

The related elements which define each of the three exhibitions suggest the cultural arcs that link the past to the present. They form trails of vapour streaming from realms of the collective unconscious and reveal gestures,machinations and the conflicting signs of social redefinition.

To consider any one of these representational strategies as the most truthful can lead to exhibits seductive in form but misleading in content. Taken together, they affirm the proposition – with some certainty – that the Holocaust cannot be contained within one essentialized perspective.

As Michael Rothberg observed in his circumspect study of Holocaust representation, “No preconceived evaluation of which media are appropriate or inappropriate (i.e., the image) to a particular event can come to terms with either aesthetic representation, historical documentation or the event they both seek to capture.”(Michael Rothberg, Traumatic Realism: The Demands of Holocaust Representation, p. 234, Univ. of Minnesota Press, 2000 London/Minneapolis.)

Rothberg emphasises the significance of transparency in the contextual elements that buttress the construction process that define the “representation.” When those elements are opaque, as in the 1965 and 1979 (government sponsored) Auschwitz illustrated historiography, then the representation is a veneer that sheaths an ideological orthodoxy.

Yet, simply labelling, or calling attention to the existence of the veneer is insufficient (as, indirectly, this exhibition itself demonstrates). The dislocations caused by massive social trauma necessitate a critical re-definition (a reawakening or reformulation) of the role and function civic institutions (and the information they impart) that substantiate and give dimension to a public history.

Inevitably, when discussing the philosophical dimensions of the Holocaust (and certainly its representation) the ideas of Theodor Adorno seep (directly or indirectly) into the discussion. Whether one agrees or disagrees with Adorno’s analysis is hardly the point, for, irrevocably, he has placed the question of Auschwitz within a continuum of ideas that define Western society.

According to Rothberg, for Adorno:

“Auschwitz does not stand alone but is part of an historical process. Adorno assigns Auschwitz a critical position in this history, but less as an autonomous entity than as a moment: Auschwitz is ‘the final stage of the dialectic of culture and barbarism.’”(Ibid. p. 35.)

At the centre of Adorno’s argument, Rothberg maintains, are the totalising qualities of a society. And, Adorno’s critics (in whatever ideological guise) “ignore the place of genocide in ‘society as a totality.”(Ibid.)

The totalising process and the realisation of the complete integration of the social machinery (civic, ideological and cultural) make genocide and mass annihilation possible.(The totalizing process (the impetus for its realization) can take place in many forms and guises and it is this systemic aspect of genocide that is most often ignored. And, consistently, it begins with a designation, a signing or labeling of the other. It is this movement of the other from the visible, to the periphery and finally to the invisible that makes an Auschwitz possible.) Adorno’s often quoted reference to the fate of poetry after the Holocaust(As Rothberg points out this reference is too often used out of context and turned into a shallow epigram.) refers to the entrenched debilitating social effects of this convergence of ‘culture and barbarism.’

And, precisely because ofthe intractability of this crippling residue, mobilising a discourse requires more than a gloss on the past but an epistemology that delves mostly completely into the stain.

The exhibition Elhallgatott Holocaust occupies the large Mucsarnok display space and was supplemented with special events and a film series. Seven curators (and the director of Mucsarnok, Dr. Fabényi Julia) puzzled together an array of paintings, installations, sculpture and performances dating from throughout the post-war period to the present.

Significantly, the exhibition moved the curatorial process into the foreground. Nemes Attila, the lead curator, and a prime organiser of the exhibition stated that, “when we started to work on this exhibition our intention was to make a kind of discourse on the subject not just an historical exhibition or remembrance or memory of victims of the Holocaust but to talk about much deeper problems brought on by the whole question.”

There seems to be little disagreement about the need to address (or access) the “deeper problems.” Nor is there a scarcity of artists or work capable of the undertaking. And, self-consciously, Elhallgatott Holocaust, with its many perspectives, suggests the degree to which the Holocaust has been an area of inquiry for artistic activity in Hungary.

However, as in the Mirroring Evil exhibition at the Jewish Museum in New York (described by one local commentator as an example of, “How pseudo artists desecrate the Holocaust”) attempts to contextualise diverse art practices within an historical or thematic frame is a risky endeavour; to venture into the territory of ‘Holocaust discourse’ can be a perilous undertaking.

That the curators chose to negotiate the hazards speaks to a sense of emerging self-confidence surrounding current Hungarian art praxis. Yet, it is at the point of ‘collective’ decision making (the juncture of contending points of view and curatorial practices) that the most problematic aspects of the exhibition become apparent.

The question arises whether (or in what manner) can an inherently unwieldy undertaking merge an array of practices into an insightful, reflective mass (prompting larger social discussion) or must it be simply a mass of artistic practices?

Exhibitions such as Elhallgatott Holocaust, because they probe processes of historical mediation, propose critical frameworks (or vocabularies) that lie outside normative (the official) historical boundaries. They challenge an official past.

Their responsibility is to originate a discourse that churns the perceptual waters that flow between the most banal perspectives of the present moment and the shadowy undercurrents of the past. That the show attracted a wide audience affirms the interest in such a re-examination.

From this vantage point, works of art (singularly or in total) are not simply objects of contemplation but rather ‘triggers’ and nearer to Roza El-Hassan’s suggestion that “When we can no longer find an answer to our questions on a conceptual level, there is still the opportunity of finding it through pictures, works of art.”(Unfortunately, El-Hassan’s video documentation and installation piece of the LIVE CHAIN ACTION ON MARCH 18 2004 was relegated to a small video monitor and wall text.)

Thus art, probing the domains of history and memory, can become a reagent of discourse substantiating and questioning the links between present and past. Art has the capacity to bring these connections into the popular consciousness.

Crossing Hosok ter, approaching the Mucsarnok, we see that its Greek revival columns are wrapped in a plastic drapery upon which (arranged vertically) are excerpts from the novel Sorstalanság by the Nobel Laureate Imre Kertész.

Also, an immense black inverted triangle – the height of the columns – inset with five inverted coloured triangles is suspended from the cornice at the centre of the facade. On either side of the building’s loggia are two large video walls on which a scrolling text is superimposed upon an overhead view of slowly moving railroad tracks.(The text is from the opening statement by the Chief US Prosecutor at the Nuremburg War Crimes Tribunal. English is on the left screen and Hungarian on the right.)

Navigating my way into the museum, I wonder about the inter-relationship of these three elements. The inverted triangle in itself would seem to be a sufficient statement.

For it is the coloured triangle, the symbol of racial, political, and social classification, that defined the Other within the Nazi scheme of inferior social beings.(Each of the five triangles was a sign of classification: dark brown – Roma; lilac – other religions; pink – homosexuals, the mentally impaired, the disabled or handicapped; yellow – Jews; and red – political prisoners. They were sewn onto an outer garment either singularly or in pairs.) And, one assumes, it is the existence and definition of otherness (and the means of its elimination) that sets the critical frame for the exhibition.

Inside the Mucsarnok, a long wall divides the three main rooms of the central exhibition space. In the entranceway to the first room, at the head of the wall, in white lettering, are two green signs. An arrow directs us to the right – majority, another to the left – minority.

Other details further elaborate and embellish this construction yet its significance, like the keel on a ship, is to add definition and ballast to an otherwise unwieldy vehicle. Conceived by János Sugár, IT’S COSY TO BE THE MAJORITY, 2004, as an architectural and thematic motif organises and stabilises the museum space.

Entering the exhibition, to the left is a room defined by historical documents and chronologies. On one end of this room is a map that indicates the locations of death camps in Germany and Poland.

Omitted from this geography are the more immediate regional and local (Hungarian, Romanian, or Serbian) sites. (Perhaps that is where history – or rather its artistic representation – can become transgressive: when it crosses borders that lie closest to home.)

The reading of history is itself a form of art, and its representation is malleable like any art form. The historical room points out the inherent difficulty in utilising facts as a means of attempting to locate art within an historical frame.

The room, rather than addressing the construction of history (or its repression: as in the example of the Auschwitz exhibit) misleadingly offers simplistic devices and decontextualised pieces of information. Furthermore, this presentation of facts establishes an unnecessary (and false) polarity between the subjective representations which propel the exhibition and data relating to Holocaust events.

Furthermore, the cramming together of data detracts from the central element in the room and the iconography that frames the exhibition. And, that is the hierarchy of otherness that the Nazis created to describe all the various social categories destined for public cleansing. It is the possibilities posed by the curatorial trajectory built upon the cleansing of otherness that expose the Holocaust to another form of scrutiny and examination.

It would have been more useful to directly link the need for some form of informational or historical grounding with the Vivo Project, the volunteer group of art history students that, most importantly, were available to guide groups or individuals through the exhibition. In this way additional materials could be created that would serve as a discussion guide or bibliography, especially for the many students that visited the exhibition.

Another aspect of the curatorial strategy was the inclusion of Roma artists and media in the exhibition.(Questions and issues relating to Roma art practices (their marginalization within Hungarian society) merit a much wider discussion.) Yet, while this inclusion is important, it reflects the problematic that encircles the exhibition and its attempt to coalesce diverse practices and media into a coherent form.

Part of this problematic revolves around the legitimacy (or illegitimacy) of the voices and representations that shape Holocaust narratives and, in this example, relates to a double form of invisibility apropos past and present social prejudices toward Roma.(At both the Budapest Holocaust Memorial and in Washington, DC there was great reluctance to include Roma as part of the standing exhibitions; at other sites Roma have been excluded a priori.)

These narratives tend to marginalise the Roma experience and knowledge of the Holocaust and exclude their representational strategies. As Timea Junghaus(Timea Junghaus is a Roma Art Historian and was one of the exhibition’s curators.) described it, Roma participation in the project involved a series of negotiations between herself and possible participants. Negotiations involved not simply the selection of work but also the nature of the process of inclusion and the selection criteria.

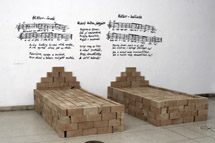

The Katalin Bodi piece ROMA COMPENSATION. “MAMO AND PAPO” and the Miklos Erdely ISTEN-ISTEN (GOD-GOD=CHEERS) radiate a severe irony and sense of pain and loss. Formed from household objects and official documents, they attest to (and extend beyond) the personal experiences and associations that form a subtext for much of the work in the exhibition.

In the pieces DOLLS I-VI (1944-2004) by Magda Watts the irony is less focused. The tableaux, composed of exquisitely crafted miniature dolls, depict scenes inside Auschwitz. But, despite their imagery, they possess a kitsch quality suspended uneasily somewhere between caricature and banality.

On the wall of the rotunda are PAINTINGD BY OMARA I-IX, 1998 by Olah Mara; in the same room, on the floor are 24 LEADBELLS, 1978-1995 by IPUT (St. Auby Tamas). The enigmatic symbolism and austerity of the bells provide an austere counterpoint to the somber blue Omara narratives.

Are the bells waiting to be hung in an invisible cathedral or perhaps they are simply remnants or artifacts. Are they bells of mourning or celebration? Here the exhibit suggests both moments (sounds?) etched in memory and despair. The underlying strength of these pieces lies not only in the stories they evoke but also the spatial juxtaposition of materials and voices/sounds.

When the Holocaust entered the arena of popular culture (and entertainment), a process of narrativization began to take place in which the co-ordinates of the historical and ethical compass took on yet another definition.

Projects such as Lego Concentration Camp by Zbigniew Libera reconfigured these co-ordinates so that the axis of vision lies near to the present. In a parallel manner, the CAFÉ INTOLLERANZA 2004 of Barbara Antal and Csaba Antal probes relationships between historical elements and contemporary culture.

As the Antals state: “Beyond a certain generation, no one has a direct experience of the Holocaust, yet it exists naturally, instinctively. For most it is a tragic fact of history they have no experience of. The structure of the menace has changed.”

Along one wall of the CAFÉ INTOLLERANZA is a battery of espresso machines, in the center of the room a vintage Mercedes. On the opposite side of the room, pastry chefs are preparing cookies.

Is this an upscale café? The first Starbucks in Budapest? And what are these cables for in the boot of the Mercedes? What are they connected to and what do they have to do with the operation of the espresso machines? Why are the pastry chefs punching-out these yellow stars?

Hidden Holocaust unavoidably straddles the language and experience of two discursive realms: one which is international in scope and the other which is local, immediate, and intimate. These spheres of discourse are inescapable.

And, it is precisely in its attempt to weave together the various representational strands that Elhallgatott Holocaust can be insightful and significant. But, there are knots in the weave. They arise from a false notion that an excess of work buys an entrance ticket into a larger discursive realm.

Consequently, works that need space in order to breathe are overwhelmed by pieces that consume space and offer little in return. What is dulled is the narrative edge (not a linear theme but a unifying vision) that would carry the project into new territory.

In opening the door to a critical subject matter and form of inquiry, in re-validating the discursive possibilities and cultural dimensions of the Holocaust, there is the sense that this was possible.

The weight of this critique is amply alluded to in the Peter Forgacs installation MISCEGENATION 2004. Skewed small chairs are arranged as in a classroom; they face a screen on which is projected a film loop documenting a public humiliation.

In violation of the laws against miscegenation, a young German man and Polish woman are taken from their home and paraded publicly down the street in what appears to be a small village. Crudely, chunks of hair are cut off. In this staging and recording of a spectacle of human desecration can be seen in the most elemental and embryonic the formation of Adorno’s ‘culture and barbarism’ dialectic.

History cannot escape the inscriptions of art nor can art evade the historical context from which it emanates. It is the ability of an individual work to both exude the specificity of its historical underpinnings and the mobilising qualities of its cultural moment that ultimately give an artistic project substance.

And I say project because the individual work –its commodity like “thingness” – in itself has transitory value. It is only in its discursive reach that a work extends beyond its own ephemeral status as commodity and achieves a poise, a tenuous equilibrium, a balancing of “thingness” and representation, between object and image, prescribing a process of mediation in which a work inscribes a particular moment in time and configures the trajectory that has placed its artistic reality in motion.