Foto: Modernity in Central Europe, 1918-1945

Foto: Modernity in Central Europe, 1918-1945, Milwaukee Art Museum, February 9-May 4, 2008.

The importance of Foto: Modernity in Central Europe, 1918-1945 extends beyond mere historical documentation. Fundamental to the exhibition’s premise is the essential role of photography in defining modernism within this region, both in art and in the culture as a whole.

The exhibition and accompanying catalogue—wonderfully curated and thoughtfully written by Matthew Witkovsky, assistant curator of photographs at the National Gallery of Art, Washington (the show’s organizer)—impart key, if not unprecedented, scholarship to an art historical narrative that often overlooks the contributions of Central European artists and movements. At the same time, it resituates familiar icons of the Western canon—Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, John Heartfield, Hannah Hoch, Hans Bellmer, August Sander, whose biographical roots are Central European—within a geo-political context that forged its own version of modernism. Seminal figures such as El Lissitzky of the Soviet Union, whose activities and sphere of influence touched ground in this region, are also included. On view are 165 original artworks, including books and illustrated magazines, by almost 100 individual artists.

The exhibition and accompanying catalogue—wonderfully curated and thoughtfully written by Matthew Witkovsky, assistant curator of photographs at the National Gallery of Art, Washington (the show’s organizer)—impart key, if not unprecedented, scholarship to an art historical narrative that often overlooks the contributions of Central European artists and movements. At the same time, it resituates familiar icons of the Western canon—Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, John Heartfield, Hannah Hoch, Hans Bellmer, August Sander, whose biographical roots are Central European—within a geo-political context that forged its own version of modernism. Seminal figures such as El Lissitzky of the Soviet Union, whose activities and sphere of influence touched ground in this region, are also included. On view are 165 original artworks, including books and illustrated magazines, by almost 100 individual artists.

Central Europe is defined here as Germany, Austria, former Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Hungary, essentially nation-states that emerged after decades as territories of empires. Captured throughout the exhibition is the dual sense of hope and despair that infused these countries during the interwar period, as is the political and social upheaval that spawned artists to craft a new vision for Europe. At the center of this new vision was photography, modern in both form and content with its ability to create “pictures of expressly modern subjects and expressly modern kinds of pictures.”(Matthew S. Witkovsky, Foto: Modernity in Central Europe, 1918-1945 (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2007), p. 91)

However, the terms of modernism played out differently in Central Europe than they did in the United States and in Western Europe. As Peter Demetz argues in his introductory essay to the catalogue, the strict division between academic photographers and amateur photographers, between modern art practices and the mass media that was characteristic of Western modernism did not exist or, at least, not to the same extent; nor did the antagonistic relationship between avant-garde artists and bourgeois society, as economic modernism “developed in a notably restricted climate” and alongside cultural modernism..(Peter Demetz, Ibid., p. 12.) Lastly, the fact that photography received institutional sanction and both state and popular support suggests that artists played central roles in staking a modernist identity for the region, one often intrinsically tied to nationalism.

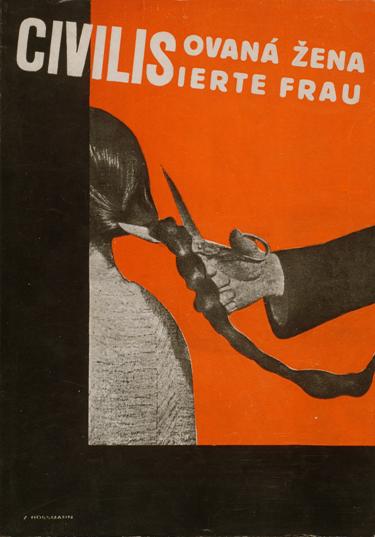

The unique, highly eclectic nature of Central European photography is explored within the exhibition across eight subthemes that survey the medium’s experimental tendencies, particularly photomontage, alongside various ethnographic studies. Likewise, images of war’s devastation are positioned in tandem with utopic visions of industry and Central Europe’s reconstruction. Other themes examine various aspects of identity, from nationhood to the changing role of women to workers’ rights. Each section flows organically to the next within the exhibition’s handsome, spacious design, the aesthetic of which remains faithful to its historical subject.

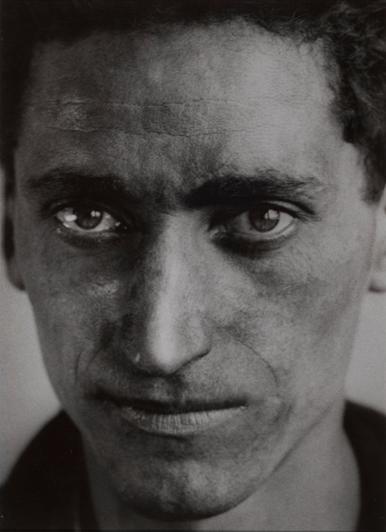

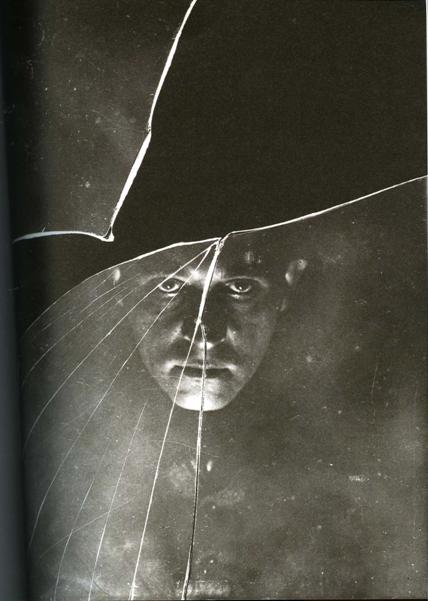

The exhibition is prefaced by two images: a c. 1910 self-portrait by Polish visionary Stanislaw Ignacy Witkiewicz and an abstract still life by Czech artist Frantisek Dritkol from 1925. Dritkol’s quasi-constructivist image of bold geometric shapes marks his shift from portrait photography to staged arrangements inspired by set designs from dance and theater.

Witkiewicz’s haunting self-portrait, which falls just outside the timeframe of the show, is more profound: the artist’s stoic face emerges from a black field yet is trapped behind a pane of broken glass. The impact of Witkiewicz’s psychological portraits, for which he is best known, is found, most notably, in the section New Women and in the exhibition’s many portraits of peasants and laborers.

Witkiewicz’s haunting self-portrait, which falls just outside the timeframe of the show, is more profound: the artist’s stoic face emerges from a black field yet is trapped behind a pane of broken glass. The impact of Witkiewicz’s psychological portraits, for which he is best known, is found, most notably, in the section New Women and in the exhibition’s many portraits of peasants and laborers.

Witkiewicz, who was also an influential writer, painter, playwright, and theorist, embodies the ethos of the modern artist, as do important artist-theorists Laszlo Moholy-Nagy and Karel Teige, whose imprints reverberate throughout the show. Their works are introduced in the exhibition’s first section “The Cut-and-Paste World: Recovering from War” devoted to the origins of photomontage, first used by the Berlin Dadaists as a form agit-prop.

Witkiewicz, who was also an influential writer, painter, playwright, and theorist, embodies the ethos of the modern artist, as do important artist-theorists Laszlo Moholy-Nagy and Karel Teige, whose imprints reverberate throughout the show. Their works are introduced in the exhibition’s first section “The Cut-and-Paste World: Recovering from War” devoted to the origins of photomontage, first used by the Berlin Dadaists as a form agit-prop.

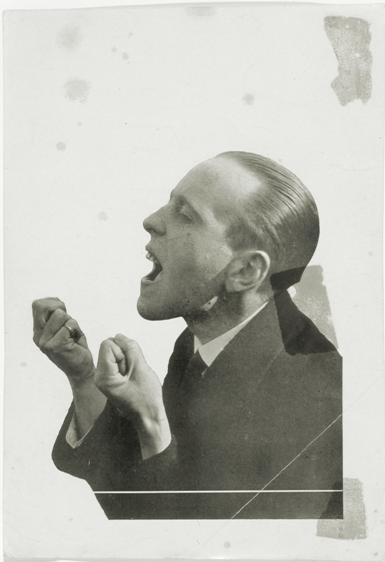

Moholy-Nagy’s Militarism (1924), juxtaposing a field of corpses before a fleet of army tanks with African figures and images from sports, still remains powerfully political. Teige, founder and spokesperson for the Prague collective Devetsil, defined photomontage as “poeticism” or “picture-poems,” a term also used by the Polish group Blok. Teige’s more spare compositions, created primarily as covers for books and magazines, meld bits of text, postcard photographs, and simple bold graphics.

One discovers in “Laboratories and Classrooms” just how widespread the teaching of photography was in Central Europe. The experimental camerawork and innovative darkroom techniques taught at the Bauhaus and championed by Moholy-Nagy in his seminal book Painting, Photography, Film (1925) were also taught at schools in Lviv, Prague, and Bratislava. Of special note is the work of Czech Jaromir Funke, whose abstract studies resemble photograms with their striking contrasts of black and white, although they are taken with the camera itself. Also of interest are the technical experiments of Witold Romer, a Polish photographer, chemist, and central figure of Polish pictorialism. In his Portrait of My Brother (1934), one sees an almost three-dimensional rendering of his brother’s face, achieved by Romer’s izohelia method, which (according to didactic information) “reproduce[s] lights and darks as a series of topographical contours.”

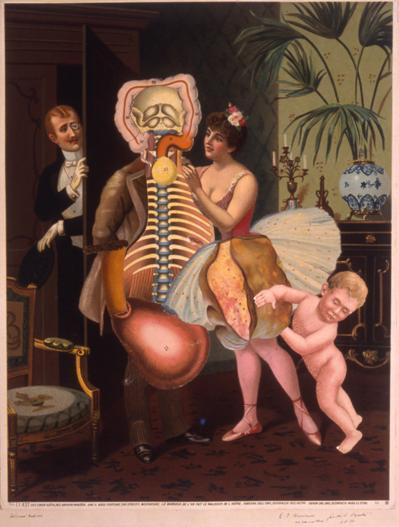

Rohmer’s physiognomic portrait contrasts with the many faces found in “New Women-New Men,” devoted to the new, more varied roles assumed by women after World War I. According to the catalogue, women filled important positions in the workforce while gaining prominence in social and cultural arenas. They also made significant contributions to the field of photography, particularly commercial photography, practicing most prominently in Germany, Austria and Hungary. Thus, we see women (Eva Besnyo, Lucia Moholy, Ringl and Pit, Trude Fleischmann, Lotte Jacobi, Yva or Else Neulander-Simon) as producers of images, using the camera as an “instrument of self-determination.”(Witkovsky, Ibid., p. 71.) Their many portraits depict women as confident, independent, fashionable, and sometimes androgynous beings, as opposed to those by their male contemporaries, for example, Hans Bellmer and Frantisek Dritkol also included here, where women remain subjects of sexual fantasy.

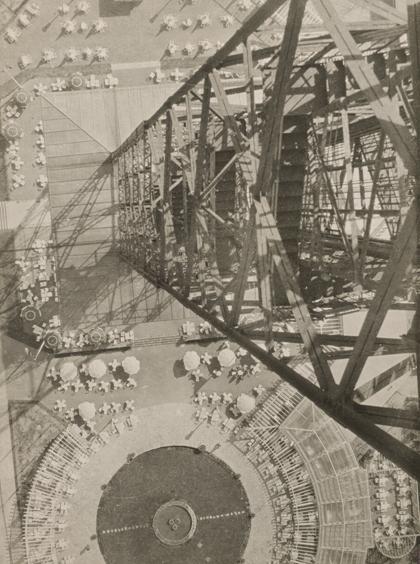

The exhibition’s central thesis, which focuses upon the shared trajectories of Central European modernism and photography, reaches its apex in the largest section “Modern Living.” Here one finds pictures of sports and leisure, neon signs and shop windows, and the construction of factories, housing projects, and bridges. Many of the region’s great architectural achievements are captured in several works by Czech and Hungarian photographers whose modern compositions, with their layered imagery, bold geometry and off-kilter framing, echo the rhythm of their urban subjects. Works by Poles Witold Romer and Antoni Wieczorek and Slovaks Sergej Protopopov and Milos Dohnany offer an alternate view of modernism, one that still embraces rural subjects and hand labor, a theme developed further elsewhere. This section is supplemented with several examples of book and magazine covers (many photomontages and photolithographs) that illustrate the fluid relationship that existed between modern art, amateur clubs, photojournalism, and the popular press.

More personal, inward responses to modernity reside in the section “The Spread of Surrealism.” In the 1930s, Prague was the second largest center for surrealist activity (the first being Paris), followed by Lviv. The studio experimentation found earlier in the show returns here, as does montage. According to Witkovsky, Central European surrealism embraced the documentary street photography of Eugene Atget. One finds his influence in the work of the Polish group Artes and in Eerie Street (1928) by the German Umbo (Otto Umbehr), where a play of distorted shadows casts an ominous air upon a city street seen from above. Czech Vaclav Zykmund’s striking self-portrait of 1936, his head bound by a taut strand of string, is an example of the kind of staged actions typical of surrealist practices in Brno.

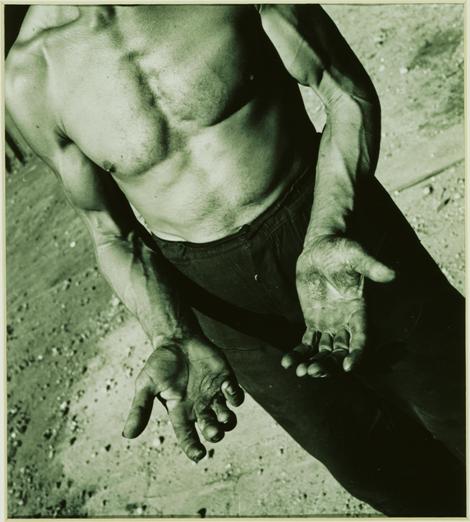

Photography as an agent of social change is explored in “Activist Documents,” where we witness powerful images of labor and its oppression. Collectively known as worker photography, this widespread movement developed throughout the region (except for Poland) initially as a photojournalistic, documentary form, but later assumed an activist, even propagandistic role. Czech Vladimir Hnizdo’s Hands That Cannot Close into a Fist because of Calluses (1936) captures the plight of workers alongside Pole Wladyslaw Bednarczuk’s Mighty Hands (also 1936), a sea of fists raised in protest. Hungarian Kata Kalman’s subjective portraits of women bricklayers, a young factory worker, and a female coal carrier (each with sullen eyes and soiled faces), are some of the most arresting photographs in the show.

In the related “Land without a Name” are several examples of Homeland Photography, rural landscapes and ethnographic portraits intended to instill a sense of patriotism and national pride. These romanticized agrarian subjects were created in reaction to modernist scenes of urbanity and industrialization, yet recognized and exploited the aesthetic potential of the photographic medium. Although unified in its content and aim, there existed within Homeland Photography various regional responses, from Polish pictorialism (Jan Bulhak, Edward Hartwig, Kazimierz Lelewicz, Antoni Wieczorek) to the Hungarian Style (Andre Kertesz, Rudolf Balogh, Gyula Pap). Rudolf Koppitz’s heroic depictions of farmers and Wilhelm Angerer’s sweeping landscapes are typical of the Austrian penchant for monumental symbolism.

The exhibition ends where it begins, with photomontage. The return of war is marked by John Heartfield’s Twenty Years Later! In Wieland Herzfelde, a 1934 photolithograph created for the cover of his popular journal AIZ. This recast of an earlier 1924 photomontage layers a German general against a line-up of skeletons and a parade of young boys costumed in military garb, suggesting the cyclical nature of war and its impact on generations to come.

The exhibition ends where it begins, with photomontage. The return of war is marked by John Heartfield’s Twenty Years Later! In Wieland Herzfelde, a 1934 photolithograph created for the cover of his popular journal AIZ. This recast of an earlier 1924 photomontage layers a German general against a line-up of skeletons and a parade of young boys costumed in military garb, suggesting the cyclical nature of war and its impact on generations to come.

Two works from Polish artist Wladyslaw Strzeminski’s series To My Friends the Jews juxtapose elements of unist abstraction with photographic images from concentration camps. Compelling works by German Marianne Brandt and Hungarian Lajos Vajda pit the promise of peace against an apocalyptic future.

Accompanying Foto is an extensive film program that explores the interrelationship between photography and film, between modernity and tradition, in Central Europe during this same time. Four films were shown in a small screening room within the exhibition. Hans Richter’s Ghosts before Breakfast (1927/1928) is a surrealist experiment with stop-action techniques, while works by Moholy-Nagy, Eugeniusz Cekalski, and Shaul and Yitzhak Goskind function as ethnographic documentaries. Foto offers a fascinating and varied portrait of modernism in interwar Central Europe. It is also an intellectual achievement for which the show’s organizers should be highly commended.

Foto: Modernity in Central Europe, 1918-1945 was organized by the National of Art, Washington. It was also on view at the Guggenheim Museum, New York, and travels to the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, June 7-August 31, 2008.