Footnotes to Discontent

2nd Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art, Moscow, March 1-April 1, 2007

The 2nd Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art was themed FOOTNOTES on Geopolitics, Market and Amnesia and added its own measure of discontent to the excess of world biennales. Now that this short-lived event is over, its outcome appears clear: the Biennale has only served to highlight the level of political uncertainty, profligate corruption, and social disparity that defines its context. In a social landscape rife with political intrigue, tightening censorship, and some 40 percent of the population living in poverty, the government’s spending of over US $2 million on the Biennale’s main projects seems to be a glaring extravagance.

This huge sum of money is especiallyhard to justify when the main projects were lacking in originality and relevance to the exhibition venues, not to mention the fact that there was a lack of any kind of correspondence between the geopolitical scene and the capital, or for that matter, the country at large. Notwithstanding the generosity of the fees paid to the various international curators, the main projects were too loosely connected to the principal biennale theme: Footnotes on Geopolitics, Market and Amnesia. This title could have had a timely reverberation when viewed in the context of contemporary Russia. The Biennale did not address the geopolitics that determine the relationship between politics and geography of a particular region, and there was an opportunity here for the selected art works to reveal something of the absurdity, nationalism, and hypocrisy of the current politics.

However, the market segment of the Biennale theme was effective in highlighting the capital’s booming economy, voraciously consuming every product regardless of its quality, merit, or providence. The Biennale served foremost the various market agendas, such as to launch Moscow into an art capital of the East or to attract the international cash flow into a dubiously prosperous economy. Both venues of the main Biennale project affirmed and heightened the power of capitalism that rules contemporary Russian society. As one might expect from a mainstream exhibition that borrows from and embellishes counter-cultural trends, the much anticipated American video art exhibition USA: American Video Art at the Beginning of the 3d Millennium (Ulrich Obrist, et. al, Curators) lost its freshness after it had already been presented in two other international venues. Considering the average curatorial selection and the small expenditure that it cost to ship the DVDs into the country, the exhibition was over-priced. The show was unimaginatively displayed along the walls in a monotonous manner, with the videos projected onto identical plasma screens. The soundtracks were also missing, and the overall effect was to leave the viewer wondering whether the silence was due to the artists’ intention or the organizers’ neglect. Both mishaps almost ruined the impact of the show.

Yet the TSUM location could offer extraordinary opportunities for the critical analysis of conceptual art because of the difference between the branding extravaganza of the shopping area and the adjoining bare concrete spaces given over to video art. If an artwork was conceived on that comparative threshold of light and gloom, scent and stench, and consumption and laboring, it could effectively retaliate against the seduction of goods, and the shallow life of the consumer. Given that the brand-obsessed life-style has almost colonized Russian society, the TSUM missed the opportunity to present a radical venue for the display of art.

Another venue that was chosen for the main project was situated on the 20th floor of the Federation Tower, which is a gaudy new skyscraper complex, still under construction in the capital’s new business district. The apt advice of an art critic who urged artists to “forget about health and safety hazards. Just have your next vodka and prepare for the chaos” served well for an hour wait in front of the showy tower in anticipation of the temporary external elevator, which promised to bring the “hungry for art” crowd to this “ivory tower” of art. Perhaps this cold and snowy wait provided a fun experience for the foreign visitors, but for locals it was merely another frustrating example of the inefficiency of the old Soviet system. When finally at the top of the tower, the project History in Present Tense, curated by Iara Bubnova, was pleasantly coherent, partially due to Boubnova’s lucid concentration on intimately familiar Eastern Europe. Her curatorial selection was highlighted by KR WP (2000), a video by Arthur Zmikewski that was full of biting irony. The score of this work features the Polish army’s Honor Guard marching and singing on the streets of a Polish town. This sequence coincided with other footage where the same soldiers rehearsed their march… naked.

In KR WP the artist strips bare the artifice of a military uniform and reveals the corruption and sexual abuse that has contaminated the Polish army. The “naked truth” is never glamorous, but in this case it offers a humiliating exposure of the entire military structure of the Soviet block.

In KR WP the artist strips bare the artifice of a military uniform and reveals the corruption and sexual abuse that has contaminated the Polish army. The “naked truth” is never glamorous, but in this case it offers a humiliating exposure of the entire military structure of the Soviet block.

As part of the main project, the exhibition Stock Zero, or the Icy Water of Egotistical Calculation by the young, prolific and highly respected curator Nicolas Bouriaud, appears notable. One wonders how Bouriaud combines his non-profit curatorial projects held at major venues around the world with his post as Collection Adviser to the richest man in Ukraine, Victor Pinchuk. Yet Bouriaud was fairly successful in the launch of his group exhibition, decked by the photographs of Jonathan Hernandez and installations by Monica Bonvicini. It is remarkable that all the main projects dutifully included at least one Russian artist, in a generous effort to supply local artwith an international context, something that it has been deprived in the past.

A third point to be made on the theme of the Biennale relates to amnesia, or the inability to recall memories of the past caused by the trauma of the 1990s. The violent shifts of that time shut down the memories of the Soviet past, in the name of either pre-Revolutionary histories, or in the wake of the prospect of a bright, modern and capitalist future. In his review, Biennale Footnotes #2, Mikhail Bode claims that ironically the Biennale failed to speak about that amnesia.1 Contrary to this view, I consider that what the Biennale reveals most is the selective process of memory and connections between private and collective imagining of the past through its representation in the present. Here amnesia takes on a specific angle, which allows every Russian to single out what to forget and remember from the Soviet past. The Russian artists nostalgically stage their themes in the morbid history of the country, whereas the projects by Vadim Zacharov, Lollypop in the Botanical Garden; Alexander Ponamarev, Secret Fairway; Olga Kiddeleva, The Artists as a Part of the Attacking Multitude; and Alexey Bulgakov, Third World War, conceptually romanticize that past. The artists long for pre-perestroika time which, although shabbier, was less vulgar than the market of today, which is ruled by financial tycoons.

A third point to be made on the theme of the Biennale relates to amnesia, or the inability to recall memories of the past caused by the trauma of the 1990s. The violent shifts of that time shut down the memories of the Soviet past, in the name of either pre-Revolutionary histories, or in the wake of the prospect of a bright, modern and capitalist future. In his review, Biennale Footnotes #2, Mikhail Bode claims that ironically the Biennale failed to speak about that amnesia.1 Contrary to this view, I consider that what the Biennale reveals most is the selective process of memory and connections between private and collective imagining of the past through its representation in the present. Here amnesia takes on a specific angle, which allows every Russian to single out what to forget and remember from the Soviet past. The Russian artists nostalgically stage their themes in the morbid history of the country, whereas the projects by Vadim Zacharov, Lollypop in the Botanical Garden; Alexander Ponamarev, Secret Fairway; Olga Kiddeleva, The Artists as a Part of the Attacking Multitude; and Alexey Bulgakov, Third World War, conceptually romanticize that past. The artists long for pre-perestroika time which, although shabbier, was less vulgar than the market of today, which is ruled by financial tycoons.

Not everything was so bleak. Several parallel exhibitions felt more engaging, and even though they were only modestly supported by independent funding, they largely sustained themselves through the enthusiasm of the curators and the insight of some relatively unknown artists. The exhibition We are Your Future at Winzavod, (an old wine factory recently converted into museum space) sketched several thought-provoking parallels between Chinese and Latin American artists who went through economic and political turmoil similar to what is befalling Russia today. The artists Tania Bruguera, Fang Lijun and Huang Yan, among others, are concerned with the burden of guilt, both collective, and personal, imposed by the recent historical cataclysms of the third world.

Not everything was so bleak. Several parallel exhibitions felt more engaging, and even though they were only modestly supported by independent funding, they largely sustained themselves through the enthusiasm of the curators and the insight of some relatively unknown artists. The exhibition We are Your Future at Winzavod, (an old wine factory recently converted into museum space) sketched several thought-provoking parallels between Chinese and Latin American artists who went through economic and political turmoil similar to what is befalling Russia today. The artists Tania Bruguera, Fang Lijun and Huang Yan, among others, are concerned with the burden of guilt, both collective, and personal, imposed by the recent historical cataclysms of the third world.

Perhaps there is a lesson here for Russian artists about the disillusionment that emerged with the heady 1990s. In contrast, the majority of the work shown by the Chinese and Latin American artists displayed a strong critique of the past yet an optimistic perspective for the future. The space of Winzavod was powerful and evocative due to the dim light, the roughness of the vault walls, and the provisional floors that barely covered the water that flows underneath. The caverns lent a post-apocalyptic stance to the controversial exhibition Veruiu (I Believe), curated by Oleg Kulik, a conceptual artist famous for his “animalia” performances in the 1990s. Kulik as auteur of the show preached his “new religion” in a self-designed Mongolian type house (urta), which attracted groups of visitors and admirers. The exhibition touched on the sensitive topic of religious restoration in Russia, and in the words of the curator “aims to recover a sense of belief or faith from the dogmatic contexts of communism and religion.” The artist Sergey Anufriev from the Gaz Group has explained his participation in the exhibition differently: “I am only taking part in this exhibition for opportunistic reasons. I know God; I know the devil. Any artist works with light and dark, and with half-tones. This means that he has to know both one and the other.”2

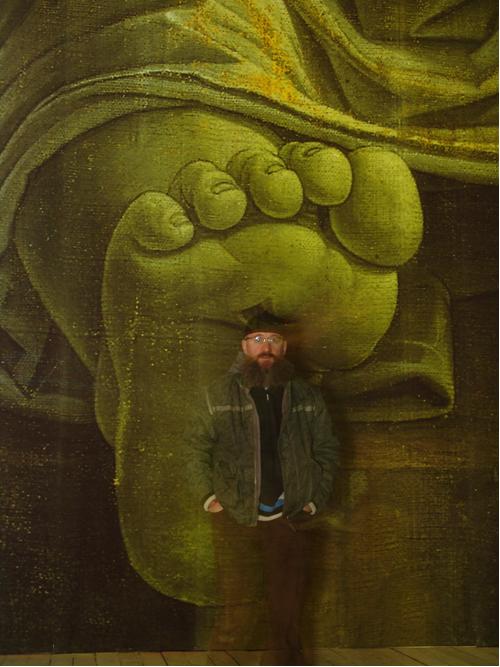

Since the Veruiu exhibition could be a subject of another review altogether, I will mention only the photograph by Dmitry Gutov that fascinates by its subversive take of religion. The artist presents a fragment of Mantegna’s Dead Christ painting, where Jesus’ feet are enlarged hundreds of times so that they almost crush the viewer under the unbearable dogmatism and cynicism of Orthodoxy. Gutov was questioned about his participation in I Believe, since the religious and all-inclusive slant of the show clashes with the outspoken Marxist orientation that the artist himself acclaims.

The very fact that the event’s second edition is less than satisfying makes one doubt the Biennale’s effectiveness for the capital. It also raises some serious questions: Does Moscow need such a transitory splash of phony art events? When international biennales are of two or three months in duration, does a one-month presentation for the Moscow Biennale justify all the money that has been spent on its realization? What benefits for the capital, for the Russian audience, and the artistic community come from hosting the biennale? Perhaps the international exhibitions should be held for longer period of time and ultimately aim to attract a wider audience from both the city suburbs and nearby towns, since these communities should be encouraged to explore the world of art and be included into the learning process. How might the next biennale be improved? By making the 2009 show less generic but fused with the country’s context. Instead of displaying how much money wealthy Russians have thrown around for gaudy treats, put that money and effort into introducing contemporary art education, developing the necessary infrastructure of independent critics, scholars and arts journals, whose foresights will be attentively deemed by the audience and the artists alike. By taking this direction the Moscow Biennale 2009 will propelled Russian art into momentum of the global scene. Alas this year’s edition could just as well have been footnoted as a spectacle of discontent.

The very fact that the event’s second edition is less than satisfying makes one doubt the Biennale’s effectiveness for the capital. It also raises some serious questions: Does Moscow need such a transitory splash of phony art events? When international biennales are of two or three months in duration, does a one-month presentation for the Moscow Biennale justify all the money that has been spent on its realization? What benefits for the capital, for the Russian audience, and the artistic community come from hosting the biennale? Perhaps the international exhibitions should be held for longer period of time and ultimately aim to attract a wider audience from both the city suburbs and nearby towns, since these communities should be encouraged to explore the world of art and be included into the learning process. How might the next biennale be improved? By making the 2009 show less generic but fused with the country’s context. Instead of displaying how much money wealthy Russians have thrown around for gaudy treats, put that money and effort into introducing contemporary art education, developing the necessary infrastructure of independent critics, scholars and arts journals, whose foresights will be attentively deemed by the audience and the artists alike. By taking this direction the Moscow Biennale 2009 will propelled Russian art into momentum of the global scene. Alas this year’s edition could just as well have been footnoted as a spectacle of discontent.