Warsaw’s Foksal Gallery 1966-72: Between PLACE and Archive

On January 21, 1967, Tadeusz Kantor(This text embraces fragments of my previously published essays: “Pulsating of the Space. Tadeusz Kantor and the economy of the Impossible,” in Jaros?aw Suchan, ed., Tadeusz Kantor. Impossible (Kraków: Bunkier Sztuki, 2000), 27-42; “Experiences of Discourse. Polish Conceptual Art from 1965-1975,” in Pawe? Polit, Piotr Wo?niakiewicz, eds., Conceptual Reflection in Polish Art. Experiences of Discourse 1965-1975, exh. cat. (Warszawa: Centre for Contemporary Art Ujazdowski Castle, 2000); “’Aneantisations’ and Matrices of Death. On Zero-Tendency in Tadeusz Kantor’s Art”, in Tadeusz Kantor. Interior of Imagination, exh. cat. (Warszawa: Zach?ta Gallery, 2005); Unbearable Porosity of Being, in Sabine Breitweiser, ed., Edward Krasi?ski. Mises en scene, exh. cat. (Vienna: Generali Foundation).) sent a special message to Foksal PSP Gallery in Warsaw. This message has not been entirely deciphered until now, but ever since it was delivered it has exerted its influence on the character of artistic experiments conducted at the gallery. The gigantic letter, which measured 2 x 14 meters, was carried by eight postal workers through the streets of Warsaw. Accompanied by photographers, they departed from the main post office and ended up in the narrow space of the gallery that was already crowded with people. Pre-recorded reports that described the letter’s progress were broadcast through loudspeakers during the event to fire up the audience. The “Man in the Black Jacket” – Tadeusz Kantor himself – orchestrated the different components of the happening, steering it cautiously towards its prescribed conclusion, the collective act of the letter’s destruction.

On January 21, 1967, Tadeusz Kantor(This text embraces fragments of my previously published essays: “Pulsating of the Space. Tadeusz Kantor and the economy of the Impossible,” in Jaros?aw Suchan, ed., Tadeusz Kantor. Impossible (Kraków: Bunkier Sztuki, 2000), 27-42; “Experiences of Discourse. Polish Conceptual Art from 1965-1975,” in Pawe? Polit, Piotr Wo?niakiewicz, eds., Conceptual Reflection in Polish Art. Experiences of Discourse 1965-1975, exh. cat. (Warszawa: Centre for Contemporary Art Ujazdowski Castle, 2000); “’Aneantisations’ and Matrices of Death. On Zero-Tendency in Tadeusz Kantor’s Art”, in Tadeusz Kantor. Interior of Imagination, exh. cat. (Warszawa: Zach?ta Gallery, 2005); Unbearable Porosity of Being, in Sabine Breitweiser, ed., Edward Krasi?ski. Mises en scene, exh. cat. (Vienna: Generali Foundation).) sent a special message to Foksal PSP Gallery in Warsaw. This message has not been entirely deciphered until now, but ever since it was delivered it has exerted its influence on the character of artistic experiments conducted at the gallery. The gigantic letter, which measured 2 x 14 meters, was carried by eight postal workers through the streets of Warsaw. Accompanied by photographers, they departed from the main post office and ended up in the narrow space of the gallery that was already crowded with people. Pre-recorded reports that described the letter’s progress were broadcast through loudspeakers during the event to fire up the audience. The “Man in the Black Jacket” – Tadeusz Kantor himself – orchestrated the different components of the happening, steering it cautiously towards its prescribed conclusion, the collective act of the letter’s destruction.

Described in the surviving score as the happening’s “formal catharsis,”(See Tadeusz Kantor, “List. Partytura,”, in Tadeusz Kantor, Metamorfozy. Teksty o latach 1938-1974 (Kraków: Cricoteka, 2000), 389.) this final stage implemented a new concept of the art object, and one that emerged in Kantor’s work during his stay in New York in 1965. Confronted with new artistic phenomena that ranged from Neo-Dada through Pop art to Minimalism, he had developed the idea of displaying art in the storage rooms of the US mail. Commenting on the project in retrospect, he wrote: “Not only were pictures to become ‘exhibits,’ but also ‘ready’ objects usually found at a post office, like parcels, packages, a mass of packs and sacks.”(Tadeusz Kantor, “Idea wystawy na poczcie,” in Tadeusz Kantor, Metamorfozy, 342.) In addition to taking the work out of the institutional context of art, Kantor’s aim was to demonstrate the status of objects that “exist for some time / on their own, without an owner, / not belonging anywhere, / without a function, / almost in a void, / between a sender and an addressee (…). This is one of those rare moments when an object escapes its destination.”(Tadeusz Kantor, “Poczta”, in Tadeusz Kantor, Metamorfozy, 343.) Kantor hesitated to comment on the project in terms of an exhibition, referring to it instead as a “situation (…), like a negative of reality.”(Tadeusz Kantor, “Uwagi Tadeusza Kantora dotyczace Galerii Foksal, adresowane do Wies?awa Borowskiego i Andrzeja Turowskiego [arch. TK] niedatowane – prawdopodobnie lato 1972 r.,” in Ma?gorzata Jurkiewicz, Joanna Mytkowska, Andrzej Przywara, eds., Tadeusz Kantor z Archiwum Galerii Foksal (Warszawa: Galeria Foksal SBWA, 1998), 410.)

The idea of the “object’s vanishing” and of display as a negative imprint of reality, contrasts with the concept of PLACE announced by the founders of Foksal Gallery in 1966. The principles of this concept, developed by Mariusz Tchorek in consultation with Anka Ptaszkowska in a statement entitled Introduction to a General Theory of Place, assumed that PLACE was essentially opaque, making it possible for the viewer to take an active attitude within it. As Tchorek wrote: “The PLACE is not transparent. What it is, is the actual presence. There are no criteria of better or more valuable filling of the PLACE. It may even be empty, but its emptiness must be conspicuously present. [sic]”(Mariusz Tchorek, et al, “An Introduction to the General Theory of Place;” in Program Galerii Foksal PSP (Warszawa: Galeria Foksal PSP, 1967).)

The Introduction to a General Theory of Place emphasized the necessity of posing a challenge to ossified institutional forms of art’s presentation. It recognized the traditional art exhibition as parasitic on advanced forms of development of modernist art (painting in particular), inferring composition from features inherent in the medium and consequently endowing it with the character of PLACE. Spurious in its transparency and neutrality, the traditional art exhibition acquires an autonomous status and imposes on its viewers a contemplative mode of reception. According to the authors of the Introduction, this model of art’s presentation had to be renounced for the sake of a more egalitarian and open structure that invites participation: “It is only in the PLACE, and not outside of it, that ‘art is created by all.’ The PLACE cannot be mechanically fixed; it must be incessantly perpetuated. [sic]”(Tchorek, “Introduction.”) Consequently, “PLACE cannot be bought or collected. It cannot be arrested. It cannot be an object of expertise.”(Tchorek, “Introduction.”)

Tadeusz Kantor protested against the Theory of Place on the occasion of its presentation at the Artists’ and Scientists’ Symposium in Pu?awy (in August 1966), several months after the inauguration of the Foksal Gallery. He claimed that its principles had been appropriated from the statements that accompanied an earlier project of his, entitled Popular Exhibition, also known as the Anti-Exhibition, shown at Cracow’s Krzysztofory Gallery in 1963. The show embraced 937 elements that did not fit within the traditional definition of a work of art. Among these were various “marginal” manifestations of artistic activity, such as drawings, designs, theater costumes, as well as objects related to the artist’s everyday functioning, e.g. notebooks, calendars and newspapers arranged in a way that went against the recognized conventions of artistic presentation. Drawings were hung on clothes lines, and other objects were arranged without any apparent plan, achieving the effect of visual overload.

Popular Exhibition questioned existing conventions of perceiving and displaying art. It was an attempt to create an “active environment” that had the capacity for changing “the viewer’s perception from analytical and contemplative to a fluent and active (…) co-presence in (…) the field of living reality.”(Tadeusz Kantor, “Manifest Anty-Wystawy,” in Tadeusz Kantor, Metamorfozy, 249-250.) The decisions made by Kantor to deny the elements of Popular Exhibition the status of works of art in the traditional sense were intended to make their commonsensical classification irrelevant. Kantor also hoped to initiate a process of combining those elements into “illegitimate” units that could not be embraced by any norms and that would thus reveal the changeability and complexity of the environment. “All I always wanted,” said Kantor, “is to achieve moments of flux, of attracting the least expected objects, and to make this state last as long as possible.”(Wies?aw Borowski, “Rozmowa z Tadeuszem Kantorem,” in Wies?aw Borowski, Tadeusz Kantor (Warszawa: WAiF, 1982), 76.)

One of Kantor’s objections against the Introduction to a General Theory of Place was that it took the form of a manifesto, endowing its signatories – Wies?aw Borowski, Anka Ptaszkowska and Mariusz Tchorek – with an illegitimate authority over artistic practice. This argument, however, is at odds with Anka Ptaszkowska memories from the 1970s. According to Ptaszkowska, the idea behind Foksal’s experiments during the first two years of its existence – 1966-67 – was to create a “platform for cooperation between artists and critics that would be beneficial to both parties and decisive for Foksal Gallery’s distinct profile.”(Anka Ptaszkowska, “List Anki Ptaszkowskiej do Grupy Foksal (na r?ce W. Borowskiego) [arch. TK] Warszawa, 17.09.1970,” in Ma?gorzata Jurkiewicz, Joanna Mytkowska, Andrzej Przywara, eds., Tadeusz Kantor z Archiwum Galerii Foksal, 400.) On another occasion, in 1967, Ptaszkowska declared that “the program adopted by Foksal Gallery is neither a recipe nor a doctrine, nor a collection of practical proposals; it implies the possibility for all kinds of schisms and surprises. Its results are unpredictable and sometimes difficult to classify. What is more, these results are sometimes unexpected for the artists who use the gallery – a public space, yet one that is, in this particular case, akin to the atmosphere in a studio – to try out tentative ideas. The idea is to try out ideas or to reject them; in short, to reveal the whole creative process.”(Anka Ptaszkowska, “The Programme and Activity of the Foksal Gallery,” in Projekt, no. 6 (1967), 52.)

Foksal’s distinct profile was partly the result of its affiliation with the so-called Pracownie Sztuk Plastycznych (Studios for the Plastic Arts; hence acronym “PSP” in the gallery’s name), a state-run organisation responsible for providing visual settings for all kinds of official events, such as the Mayday manifestations, the governing Polish United Workers’ Party congresses, and visits by politicians). The PSP also produced and installed monuments commemorating important people and historical events. Foksal Gallery’s financial and administrative dependence on PSP brought with it the possibility of deploying a whole range of facilities and materials for the production ofexperimental art. This paved the way for implementing a new gallery model, one focusing on revealing the intricacies of the creative process rather than presenting works of art in their finished form. The introductory note inserted into the catalogue for the first Foksal exhibition, which opened on April 1, 1966, stated that, “two aspects will be emphasized in the exhibitions organized by the gallery. In the first place it will attempt not so much to show works as ‘finished’ products, but to reveal certain particular conditions and circumstances surrounding their creation. Secondly, Foksal proposes to treat these conditions and circumstances as organic elements in the display of art. We want to disturb the sanctioned division between two isolated domains of artistic activity: the studio, where the work is created, and the exhibition space, where it is displayed.”(Statement published in Zbigniew Gostomski, Edward Krasi?ski, Roman Owidzki, Henryk Sta?ewski, Jan Ziemski, exh. cat. (Warszawa: Galeria Foksal PSP, 1966).)

This concept of the art exhibition as an organic unity that loses its secondary character in relation to the work of art, becoming an “artistically active form,” provided a broad theoretical stage for a number of projects presented at the gallery in the years 1966-67. Initially discussed in the introduction to the inaugural 1966 exhibition catalogue and then developed in the Introduction to a General Theory of Place, the idea of PLACE questioned the rigidity of artistic orthodoxy. Instead, it aimed to initiate the free play of artistic ideas, reflecting different aspects of the notion of PLACE and enriching it with unexpected connotations. It is worth emphasizing the formal aspect of the notion of PLACE: rather than prescribing a direction for the development of art, it reflects upon the conditions of its possibility.

The projects organized at Foksal Gallery early after its opening fall into three different categories. The first embraced exhibitions that inferred the principles of spatial arrangement from the actual dimensions and proportions of the gallery space. This was the case with an installation created in June 1967 by Henryk Sta?ewski, an artist of Constructivist descent. The project reflected the idea of extending a formula for the construction of a color relief over the entire exhibition space. A number of individual objects – reliefs displayed on the gallery walls and a spatial construction placed on a cylindrical pedestal – were inscribed into a larger structure consisting of differently colored squares both on the floor and suspended from the ceiling. The installation’s dynamic effect resulted from the color gradation that occurred between neighboring modules, ranging from yellow-green to deep blue, and from their diagonal shifts in relation to the angular structure of the exhibition space.

Another exhibition, conceived by Zbigniew Gostomski in February 1967, employed what he called “constant value contrast,” an idea for creating an environment derived from the artist’s earlier Optical Objects. As Ptaszkowska wrote, “Zbigniew Gostomski treats the gallery’s rooms as a canvas whose measurements were an unalterable starting point determining everything that follows. Black rectangles, which seem to be cut out of the gallery’s interior and that precisely replicate its measurements are inclined at various angles towards each other and towards the actual walls. This gives the illusion that the whole interior is swaying; an identical white rectangle on the wall intensifies this effect. One has the impression that the artist holds the entire room in his hand and composes the picture within it, regardless of any outward considerations or conditions. And so a surprising situation arises: Gostomski has created a picture, but it cannot be fully seen because the viewer is standing at its very centre.”(Anka Ptaszkowska, “The Programme and Activity of the Foksal Gallery,” 53.) The element of participation inscribed into Gostomski’s environment relates to the idea of “uneasy perception” that can already be found in the Introduction to a General Theory of Place and other texts written by Foksal’s founding critics. This effect was further enhanced by experiments belonging to the second category of early Foksal projects. These projects renounced the static character of arrangements in space and involved an element of interactivity.

The painterly heritage that was still present in Sta?ewski’s and Gostomski’s projects was effectively neutralized in a series of five quasi-musical events organized in September 1966 by composer Zygmunt Krauze together with visual artists Grzegorz Kowalski, Henryk Morel, and Cezary Szubartowski. The project, entitled 5x, emphasized the richness of the sensual experience involved in manipulating a range of materials gathered in the gallery space: tin plates; metal rings; nets and folds of canvas suspended from the ceiling; and metal objects positioned on the floor. The visitors’ participation gave the artistic act the character of a social event – one of the things emphasized by Tchorek in his Theory of Place.

The trans-individual character of perception also manifested itself in projects by W?odzimierz Borowski and Edward Krasi?ski. These constitute the third category of projects at Foksal Gallery. On the occasion of the inauguration of his 2nd Syncretic Show, opened in June 1966, Borowski refused to let the visitors access the exhibition space and instead confronted them with spiny objects suspended from the ceiling in the entrance area. In addition, he submitted the visitors to the effects of blinding light flashing at regular intervals, accompanied by a red sign that read “silence.” Hiding himself inside the exhibition space, Borowski observed the onlookers through rectangular mirrors that were also suspended from the ceiling. By initiating a process of ocular exchange, the artist effectively exposed the power relations inscribed into the institutional mechanism of art presentation.

Edward Krasi?ski’s exhibition in December 1966 consisted of a number of fragmentary objects bathed in light that created effects of dramatic rupture. The effect of coherence in this exhibition resulted from the inclusion of a spectacular “serpent” – a swirling piece of thick cable that extended from the back wall of the gallery to the entrance into the adjacent room. The serpent was supplemented by “ruptured” constructions; a partly painted, welded iron sculpture; and two other constructions that were displayed in the main exhibition space where vertical arrangements of table-tennis balls produced an effect of animated movement. Krasi?ski installed a corridor in the gallery, transforming it into a maze and emphasizing the expansive character of the serpent-like form.

Borowski’s and Krasi?ski’s exhibition projects involved a multiplicity of viewpoints that corresponded with the idea of perception inscribed into Tchorek’s Theory of Place. Another text by Tchorek, entitled “The Disclosed Picture” and published in spring 1967, related the experience of PLACE to the unexpected recognition of a painting’s ontological status. Referring to the artistic tradition of depicting paintings within pictures, Tchorek argues that in order to renounce our imaginary bond with a painting’s pictorial qualities and to reflect on our position towards it we have to shift our point of view to the one implied by the depicted – as opposed to the depicting – painting. “A picture within a ‘picture,’” Tchorek writes, “is the flash in which we grasp our otherwise inaccessible way of grasping a painting. Its presence may scare us, it may be a warning, a frustration of our calmness, or it may signal a loss of confidence in the legitimacy and competence of our faculty of sight concerning the art of painting.”(Mariusz Tchorek, “The Disclosed Picture (1),” in Program Galerii Foksal PSP.) What this passage suggests is that in order to actively be in a place, we have to reflect on our perception of it.

In a letter written to Foksal in 1972, Tadeusz Kantor criticized the exhibitions that took place at the gallery in the years 1966-67, characterizing them as “camouflaged Constructivist shows” that submitted to traditional conventions of “artistic shaping.”(Tadeusz Kantor, “Uwagi Tadeusza Kantora dotyczace Galerii Foksal, adresowane do Wies?awa Borowskiego i Andrzeja Turowskiego [arch. TK] niedatowane – prawdopodobnie lato 1972 r.,” in Ma?gorzata Jurkiewicz, Joanna Mytkowska, Andrzej Przywara, eds., Tadeusz Kantor z Archiwum Galerii Foksal, 408.) He emphasized the anti-Contructivist slant of his own work with its “tendency towards dematerialization, and its strong connections to the experience of Marcel Duchamp.”(Kantor, “Uwagi Tadeusza Kantora,” 408.) Kantor evidently viewed the concept of PLACE as an artistic program in the strict sense of this term, confronting it with his own idea of an “active environment.” He had little time for formal aspect of the Theory of Place and its preference for general approaches over specific instructions.(Mariusz Tchorek, et al, “An Introduction to the General Theory of Place.”)

There are, however, more fundamental reasons for Kantor’s disagreement with the Theory of Place. His Popular Exhibition (1963) seems to have played a crucial role here. It was on this occasion that Kantor decided to submit his own artistic output to a process of “degradation.” Endowing fragments of his own works with the status of ready-mades resulted in shifting his artistic practice to the imaginary field where it figured “not as material for construction … but as a room into which objects from my own past were falling in the form of wrecks and dummies …, valuables and trifles, letters, recipes, addresses, traces, dates, meetings. It was an inventory deprived of chronology, hierarchy and localisation. I found myself in the middle of it all, without a prescribed role.”(Tadeusz Kantor, “Okolice zera,” in Tadeusz Kantor, Metamorfozy, Teksty o latach 1938-74, 246.)

In the way it privileged vanishing or absence over presence, Kantor’s concept of the work of art as inventory challenged the notion of Place. With the delivery of his gigantic Letter to the Foksal Gallery, the theoretical assumptions implicit in Kantor’s Popular Exhibition started to retrospectively replace the principles of the Theory of Place, affecting subsequent decisions regarding the Gallery’s policy. This theoretical schism within the gallery, which gradually increased in the years 1967-68, did not go unnoticed. In 1968, the art critic Andrzej Kosto?owski, remarked that PLACE could not efficiently explain the temporal aspect of happenings.(See Andrzej Kosto?owski, “Galeria i krytyka (2). Miejsce,” in Wspó?czesno??, no. 16 (1968).)

Kantor strongly emphasized the dependence of his practice on the happening. His interest in procedures of dematerialization and degradation that could effectively reveal the negative side of objects coincided with Wies?aw Borowski’s view of the evolution of 20th-century art as a progressive “elimination of art from art.” In a text published under this very title in 1967 by the Foksal Gallery PSP Programme, Borowski diagnosed the effective neutralization of modernism and its conventions for creating and perceiving art. “Some sort of deserted area or void is produced,” he wrote. “It is not a negative void, but one that is real and meaningful.”(Wies?aw Borowski, “Elimination of Art from Art,” in Program Galerii Foksal PSP.) He added: “Elimination and negation in art are by no means artistic tendencies: otherwise they would have reached their aim long ago. They are an opening of artistic possibilities that the art market cannot provide.”(Borowski, “Elimination of Art from Art.”)

Borowski’s ideas regarding the role played by elimination and negation in art coincided with the assumptions behind Kantor’s Panoramic Sea Happening that was organized by Foksal and performed on August 23, 1967. In this performance the boundaries of PLACE suddenly expanded and came to include the vast expanse of the Baltic Sea and the beach at Osieki. The activities performed during that happening included conducting waves; “spreading the stickiness” of the sand mixed with tomato sauce by means of female bodies; planting rolled up newspapers in the sand; staging a life performance of Gericault’s painting The Raft of Medusa and, last but not least, submerging in the sea a box with Foksal Gallery documents.(See Tadeusz Kantor, “Panoramiczny happening morski. Partytura,” in Ma?gorzata Jurkiewicz, Joanna Mytkowska, Andrzej Przywara, eds., Tadeusz Kantor z Archiwum Galerii Foksal, 126-166.)

The change in parameters for the work of art implicit in Kantor’s happening questioned a model of the environment that was static and self-contained. It exposed art to the domain of the boundless, the un-representable, and the impossible. Kantor’s artistic practice in the late 1960s conceived of art as something “FORMLESS, / DEVOID OF AESTHETIC VALUE, / DEVOID OF ENGAGING VALUES, / WITHOUT PERCEPTION, / IMPOSSIBLE, / THAT IS TO SAY, POSSIBLE ONLY THROUGH CREATIVITY!”(Tadeusz Kantor, “Manifest 1970. Cena istnienia,” in Tadeusz Kantor, Metamorfozy, Teksty o latach 1938-74, 493.)

In the way it exceeded the principles of the Theory of Place, Panoramic Sea Happening also highlighted the necessity of its reformulation. Together with Borowski’s “elimination of art from art,” Kantor’s idea of art’s escaping the determining influence of space and time prompted a new round of self-questioning at the gallery and the publication, in December of 1968, of a programmatic text entitled “What Do We Not Like About Foksal PSP Gallery?” Just as the Introduction to a General Theory of Place had questioned traditional views of the art exhibition, this new declaration addressed the traditional model of the gallery with its governing rules for organizing exhibitions, its attachment to a specific location, and its uncritical self-promotion. “What Do We Not Like About Foksal PSP Gallery?” focuses on a type of active artistic intervention whose temporal and spatial parameters it defines as “NOW” and “EVERYWHERE.” The exclamation “Let’s look for undefined places!”(Co nam si? nie podoba w Galerii Foksal PSP?, in Ma?gorzata Jurkiewicz, Joanna Mytkowska, Andrzej Przywara, eds., Tadeusz Kantor z Archiwum Galerii Foksal, 422.) breaks once again with the notion of the work of art as a static environment, endowing it with greater dynamism and heightened activity.

The question is whether such formulations simply mark an extension of the concept of PLACE or if, on the contrary, they narrow it down. Significantly, Assemblage d’hiver, a project organized by the gallery as an artistic companion-piece to the 1968 declaration, was designed for an indefinite duration and continued intermittently until the end of April 1969. In her description of this project, Ptaszkowska associated it with the Situationist idea of making interventions in the homogeneous space of spectacle: “Assemblage d’hiver started in January 1969. Within its structure every artist conducts an independent activity. He or she undertakes or abandons this activity at a moment in time chosen arbitrarily, acting alone or in public. Assemblage d’hiver is not subject to the kind of temporal determinants that link it to a spectacle; it is a permanent and secular action. Assemblage d’hiver is not confined to a particular place. It takes place both within the gallery space and outside of it. It may expand into the streets, take possession of the facade, become suspended in the air, etc.”(Anka Ptaszkowska, Happening w Polsce(3), in Wspó?czesno??, no. 11 (1969).)

Inspired by Tadeusz Kantor, Assemblage d’hiver involved covering the gallery’s windows with thick layers of crumpled packing paper (Zbigniew Gostomski); painting the gallery thresholds and the trees outside (Maria Stangret); taking care of “Easter eggs” (Jerzy Bere?); and unrolling an “endless” blue cable in the streets of Warsaw (Edward Krasi?ski). It would be difficult to say to what extent these activities took possession of the city space. In another performance carried out around that time by five of Tadeusz Kantor’s students (Mieczys?aw Dymny, Jan Lis, Stanis?aw Pietryszyn, Stanis?aw Szczepa?ski and Tomasz Wawak) this certainly did occur. As a provocation to the people in the street they walked around Warsaw wrapped up as a large parcel addressed to Foksal Gallery.

Kantor’s contribution to Assemblage d’hiver had consisted, among other things, in strengthening the idea of the work of art as being in a state of suspension between sender and addressee, a position already hinted at in the Letter happening. On the day of the opening of Assemblage d’hiver, he performed an action entitled Typing Machine with Sail and Steer. Surrounded by the audience Kantor typed his most important ideas regarding the nature of art on sheets of paper, rolled them up and locked them in a cylindrical container that was then suspended from the ceiling. During the performance he inscribed the following statement on the gallery wall: “Down with so-called participation.” With this statement Kantor effectively cancelled the concept of PLACE as it had been proposed by Mariusz Tchorek. What is more, he brought about a theoretical split in the Foksal gallery community, demanding from its members to choose between a model of art as an isolated message, on the one hand, and the formal idea of PLACE, on the other.

It is difficult to say if Kantor’s interventions had a positive or negative effect on the development of Foksal Gallery. One thing is certain: his ideas and artistic proposals contributed to changes in the gallery’s policy and to its decision, around 1970, to promote Conceptual art. The model of Conceptual reflection implicit in Kantor’s practice corresponded with ideas developed at that time by Zbigniew Gostomski and others. On the occasion of the 1970 Artists and Scientists symposium in Wroc?aw, the artist proposed a work that was to be of key importance for Polish Conceptualism. Fragment of the System (also known as It Begins in Wroc?aw) provided a visual grammar of the rules that determined the construction of Gostomski’s earlier Optical Objects. The accompanying description of the project provided the city of Wroc?aw with three types of urban development corresponding to three symbols (O, /, Ø). Gostomski had these three symbols inscribed on a map of the city without, however, defining in any way the form the developments that correspond to the symbols would take. The type of system corresponds to Gostomski’s project’s most basic idea, which was to call for a “never ending development extending further and further in all directions.”(Zbigniew Gostomski, Fragment of the System as reproduced in Pawe? Polit, Piotr Wo?niakiewicz, eds., Conceptual Reflection in Polish Art. Experiences of Discourse 1965-1975, 82-83.) The work of art as a closed circuit limited by the laws of its own composition has been transgressed here for the sake of a disinterested activity, unlimited in time and space, inscribed within an order of repetition: “It begins in Wroc?aw. It could be started anywhere. / it begins in a definite area, / but it need not end there. / It is potentially endless.”(Gostomski, Fragment of the System, 82-83. Play best io games at iogames.center site.) Zbigniew Gostomski proposed a model of a work as “absolute environment.”

Tadeusz Kantor’s work, too, gradually lost its material support and acquired the status of a support for mental processes. Among the most extreme manifestations of Kantor’s struggle to isolate the work’s message are his Emballages Conceptuelles (1970) which call for the (impossible) packaging of objects such as an Achilles heel, Cleopatra’s nose, or what Kantor called “the eye of Providence.”

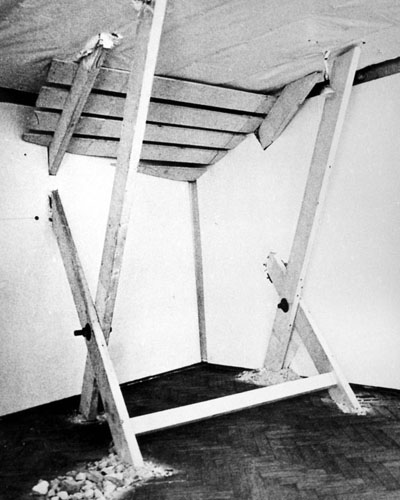

In the second half of the 1960s, the object in Kantor’s art objects acquired attributes that could only be explained by conceptual means. In this category we find objects whose scale exploded the context for which they were designed. The projects proposed by Kantor for the 1970 Symposium in Wroclaw – a huge clothes hanger, a light bulb, and a chair, all of them designed to be placed in the urban environment – were meant to undermine the naïve belief in the “reality of the world.” Instead, they were to display their own reality, enhanced by the relatively humble functions with which they were associated. The arrangement of a huge chair that hardly fit into the space allocated for it in the gallery (Cambriolage, 1971) demanded that one imagined the missing parts as being located in the adjacent rooms.

In the second half of the 1960s, the object in Kantor’s art objects acquired attributes that could only be explained by conceptual means. In this category we find objects whose scale exploded the context for which they were designed. The projects proposed by Kantor for the 1970 Symposium in Wroclaw – a huge clothes hanger, a light bulb, and a chair, all of them designed to be placed in the urban environment – were meant to undermine the naïve belief in the “reality of the world.” Instead, they were to display their own reality, enhanced by the relatively humble functions with which they were associated. The arrangement of a huge chair that hardly fit into the space allocated for it in the gallery (Cambriolage, 1971) demanded that one imagined the missing parts as being located in the adjacent rooms.

Wies?aw Borowski associated Gostomski’s and Kantor’s practices with what in a 1971 article he called an “apictorial strand at Foksal PSP Gallery.” Borowski understood innovative artistic abstraction not as a “visual (sensual) qualification of the work” but as the “ability to embrace the whole of the creative process, the capacity for thought and consciousness.”(Wies?aw Borowski, Nurt apikturalny w Galerii Foksal PSP, in Poezja, no. 5 (1971), 104.) Adhering to the disinterested model of art promoted by Kantor in his 1970 Manifesto, Borowski privileged function over perception: “These works are not addressed to any viewer. They assert the constant presence of illegitimate and disinterested actions that do not demand justification now or in the future, nor do they preserve such actions by any means. These actions are immediate, casual, and tied neither to a place nor to any material, or time.”(Borowski, Nurt apikturalny w Galerii Foksal PSP, 104.) The works Borowski discusses were, in a word, placeless.

This idea of the “placeless” work of art received a positive evaluation in two statements published by Foksal Gallery in August 1971. Authored by Wies?aw Borowski and the young critic Andrzej Turowski, these utopian statements postulated the work of art as an isolated message in a pristine virtual state and unaffected by the operations of sending and receiving. Adopting the metaphor of communication from Kantor, Borowski and Turowski refer back to his idea of the art work as a negative form beyond expression and perception. The first of their texts, entitled Documentation, quoted a passage from the script of the Panoramic Sea Happening that described the submersion of the Foksal Gallery’s archive. In this text, the two authors critically assessed the institutionalized conventions of preserving and documenting art, a practice that in their minds reduced it to the status of a fetish: “Without our noticing it, DOCUMENTATION has become identical with the museum and the collection, assuming their forms and manners.”(Wies?aw Borowski, Andrzej Turowski, “Dokumentacja,” in Ma?gorzata Jurkiewicz, Joanna Mytkowska, Andrzej Przywara, eds., Tadeusz Kantor z Archiwum Galerii Foksal, 424.)

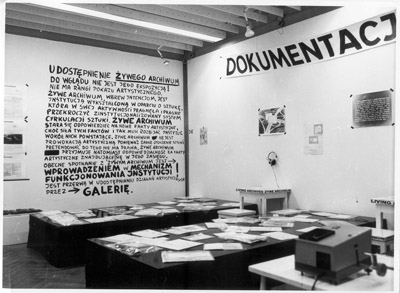

The second document, entitled Living Archives, was a positive program for the reformulation of Foksal’s operating principles that made it possible to recognize a work of art as “neutrally present,”(Wies?aw Borowski, Andrzej Turowski, “?ywe archiwum,” in Ma?gorzata Jurkiewicz, Joanna Mytkowska, Andrzej Przywara, eds., Tadeusz Kantor z Archiwum Galerii Foksal, 425.) i.e., disentangled from the conditions of everyday-life and interpretation. It radically proposed to see the work of art as the trace of a living thought that is recognized in its past condition: “LIVING ARCHIVES marks the past condition of a thought vis-à-vis its presentation.”(Borowski, “?ywe archiwum,” 425.)

Living Archives implied yet another modification of the Foksal model. In September 1971 and from June to September 1972, the gallery exhibited documents that were sent in by its critics upon Borowski’s and Turowski’s request. These documents were arranged in the form of a reading room and accompanied by a statement inscribed on the gallery wall that denounced the gallery’s status as an “art display.” The idea was to replace such display with a new kind of institution – one that would be sensitive to new artistic facts.

Living Archives implied yet another modification of the Foksal model. In September 1971 and from June to September 1972, the gallery exhibited documents that were sent in by its critics upon Borowski’s and Turowski’s request. These documents were arranged in the form of a reading room and accompanied by a statement inscribed on the gallery wall that denounced the gallery’s status as an “art display.” The idea was to replace such display with a new kind of institution – one that would be sensitive to new artistic facts.

When he was asked in 1998 whether the idea of art as an “isolated message” coincided with his understanding of Conceptual art, Turowski negated this question and pointed to a series of important worldwide exhibitions where the notion of the “isolated message” played a role (January 1-31, 1969; Op Losse Schroeven; Prospekt 69; and When Attitudes Become Form).(See Pawe? Polit, “On Conceptual Art. Interview with Andrzej Turowski,” in Pawe? Polit, Piotr Wozniakiewicz, eds., Conceptual Reflection in Polish Art. Experiences of Discourse 1965-1975, 211-213.) Turowski himself, however, subscribed to a different, more analytical model of Conceptualism that sees in the individual work a theoretical statement. In that respect he differed radically from Kantor and Borowski. In an essay entitled “Remarks on the Definition of Art” (1972), Turowski linked Conceptualism to a definitional practice he qualified as tautological.(Andrzej Turowski, “Remarks on the Definition of Art,” in Pawe? Polit, Piotr Wo?niakiewicz, eds., Conceptual Reflection in Polish Art. Experiences of Discourse 1965-1975, 244.) It should be borne in mind, however, that Turowski’s ideas emerged in isolation from the artistic practice of Polish artists at the time. Even though we can distinguish between certain theoretical positions in the works of artists who cooperated with Foksal during the Conceptualist era – Zbigniew Gostomski, Stanis?aw Drozd?, Jaros?aw Koz?owski and Krzysztof Wodiczko, among others – the analytical model of Conceptualism did not exist as a specific phenomenon in Poland, reflecting instead the global dimension of Conceptual art. In any event, it will by now be abundantly clear that Turowski’s analytical model did not sit well with the initial Theory of Place.

This essay was originally commissioned by Afterall and the Academy of Fine Art, Vienna, for the symposium “Conceptual Art and its Exhibitions,” which took place on May 29, 2008 at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. It appears here in significantly altered form.