Femina Subtetrix: A Feminist Look at the APACA Textile Factory

Femina Subtetrix at Ivan Gallery, Bucharest, September 10 – October 3, 2015

Sonja Hornung, a Berlin-based artist, and Larisa Crunteanu, an artist from Warsaw and Bucharest and former curator at Atelier 35 in Bucharest, produced a culturally layered exhibition at Ivan Gallery, curated by Xandra Popescu, entitled Femina Subtetrix. Hornung and Crunteanu both come from a feminist background. Hornung is a sculptor who investigates the relationship between material, memory and public space; Crunteanu works in performance and video art with a strong interest in the social image of the body and performativity. In this collaborative exhibition, both share a material-driven interest in the processes of privatization during the transition from socialism to capitalism in Bucharest, and in an archaeology of the history of the “women of APACA.”

The artists appropriated a Romanian national myth in relation to the rise and fall of APACA, one of southeastern Europe’s most prominent textile factories operating from 1948 with mainly female employees. Crunteanu and Hornung collaboratively created a set of sculptures, photographs and video works through which they analyzed old and new models of femininity. Incorporating materials such as concrete, stone and rubble into their abstract sculptures, the artists traced the former workers’ experiences and reflections on their working lives in (post-) socialist Romania.

Layer by layer, Hornung and Crunteanu excavated hidden figures and motifs of the APACA employees excluded from the official narrative of that place. However, in the exhibition, the everyday labor of the women, their networks and forms of solidarity remained as foreign as the clothes they produced. What is the reason for the absence of the “APACA girls” within the exhibition? Crunteanu and Hornung placed their focus on the processes of privatization and women’s complicated position in pre- and post-revolutionary Romania. As will become clear in the following, the strategic absence of the women workers within the displayed works links Femina Subtetrix to “feminist counter-narrative[s]”(See: Alison Hugill, “A Speculative Fiction: Femina Subtetrix,” in Revista Arta, September 21, 2015. Link: http://revistaarta.ro/en/a-speculative-fiction-femina-subtetrix/.) inspired by a re-evaluation of the post-socialist “female ideal” from a demystifying and gender-critical perspective.

APACA was rebuilt in 1948 under the official name of Gheorghe Gheorghiu Dej. At its peak, the workplace employed more than 18,000 women; today, in parts of its former complex there exist three smaller textile companies employing around 700 workers. In 1991, one year after the Romanian Revolution, the then popular Prime Minister of Romania, Petre Roman, visited the APACA factory and was allegedly enthusiastically welcomed by the female workers. According to media reports, the women chanted: Nu vrem Kent! Nu vrem valut?! Vrem pe Roman s? ne fut?! (“We don’t want Kent! We don’t want foreign currency! We just want your sex!”)(Link to a newspaper article: http://www.infobraila.ro/2013/02/viralul-anilor-%E2%80%9990-in-politica-%E2%80%9Cnu-vrem-kent-nu-vrem-valutavrem-pe-roman-sa-ne%E2%80%A6%E2%80%9D-in-2000-anunta-ca-%E2%80%9Cel-mai-poate%E2%80%9D-a-mai-putut-doar-de-3/; Link to a related video: http://lamaruta.protv.ro/video/petre-roman-despre-celebrul-sau-pulover-rosu.html.). This welcoming scene can be traced back to past defamatory rumors about the women of APACA concerning their sexual desire, their skills and secret services. In the decades before 1989, these women were considered as compliant, progressive and equal female socialist workers in a showcase factory—a place in which state visits were on the annual agenda. Under the surface, the public perception of these women workers had already been damaged shortly after the inauguration of APACA. In 1949, the anti-prostitution law was passed by the Socialist Republic of Romania, prohibiting prostitution in the newly founded republic. The enforcement of Decree 351 led to the closure and disappearance of the prostitution district Crucea de Piatr?. At that time, APACA was seeking new workers and hired many of these women. From this point on, APACA has been confronted with the rumor that its employees were shameless, promiscuous and vulgar, projections that contributed to the “APACA girls” label.

With this history in mind, and despite numerous interviews with the former female workers, Crunteanu and Hornung’s exhibition concentrates on a radical material abstraction of the women’s experiences. The first untitled work one discovered upon entering the exhibition was a concrete cube with two opposing apertures, each about the size of a fist. An exhibition text encouraged visitors to put their hands inside each hole and to “Reach out to each other.” In some cases, visitors managed to touch another visitor’s fingertip;—as one feels the cube’s soft, hand-shaped and waxed cavern and the eventual trace of the other person’s body warmth, the work invokes the notion of a conceiled “proto-feminist”(For understanding the lack of feminist art, “pro-feminist” and “proto-feminist” works during communist systems, please read: Bojana Peji?, “Proletarians of All Countries, Who Washes Your Socks? Equality, Dominance and Difference in Eastern European Art,” in GENDER CHECK. Femininity and Masculinity in the Art of Eastern Europe, ed. Bojana Peji? (Wien: MUMOK Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien; Cologne: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, 2009), 17.) lady- or sisterhood in the factory.

With this history in mind, and despite numerous interviews with the former female workers, Crunteanu and Hornung’s exhibition concentrates on a radical material abstraction of the women’s experiences. The first untitled work one discovered upon entering the exhibition was a concrete cube with two opposing apertures, each about the size of a fist. An exhibition text encouraged visitors to put their hands inside each hole and to “Reach out to each other.” In some cases, visitors managed to touch another visitor’s fingertip;—as one feels the cube’s soft, hand-shaped and waxed cavern and the eventual trace of the other person’s body warmth, the work invokes the notion of a conceiled “proto-feminist”(For understanding the lack of feminist art, “pro-feminist” and “proto-feminist” works during communist systems, please read: Bojana Peji?, “Proletarians of All Countries, Who Washes Your Socks? Equality, Dominance and Difference in Eastern European Art,” in GENDER CHECK. Femininity and Masculinity in the Art of Eastern Europe, ed. Bojana Peji? (Wien: MUMOK Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien; Cologne: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, 2009), 17.) lady- or sisterhood in the factory.

The 1980s at APACA brought further raw material for rumors: catwalks were installed in the factory’s showrooms, populated by fashion models with ambiguous connections to political and higher management circles. This negative image reached its peak in the nineties with Roman’s first visit to the factory. In a time of hope and optimism, it was hardly foreseeable that the main area of APACA would soon turn into a decaying industrial ruin swimming “through the muddy waters of transition and privatization.”(Curator Xandra Popescu in the press release, published by Ivan Gallery.) But the women of APACA were already feeling these eruptions. Their slogan affirmatively appropriated the rumors about their sexuality. Their shouting in the face of the new “star politician” seems like an ironical revenge for his inability to address any of the current political or economic urgencies the women must have had at that time such as the “triple burden” of paid labor, housework and forced maternity because of illegalized abortion. Naming and refusing two simple desires of those times: luxury goods, such as Kent cigarettes (“We don’t want Kent!”) and a reliable currency (“We don’t want foreign currency!”), the women workers autonomously decided to amplify and distort their public image by celebrating and ironically objectifying Roman like a desirable popstar.

Throughout their extensive research, Crunteanu and Hornung became especially interested in one symptomatic moment. In 1996, when the factory had already been privatized and diminished in size, Roman—this time as a presidential candidate—visited APACA again. On this mediatized occasion, he spontaneously decided to kiss one of female workers on her forehead, presenting himself as a popular leftist womanizer who kisses an “APACA girl.” The woman, obviously in the midst of speaking to him, is vigorously interrupted by his kiss captured by prime-time TV news. After the restructuring and privatization of the nineties and within the context of the shaken textile industry, this event turned into an iconic paternalistic gesture undermining the self-empowering shouting and actions by the collective female workers some years earlier. For Crunteanu and Hornung, this gesture marks the center of the women’s subjective experiences in a profoundly patriarchal society in which neither women’s disadvantaged socio-economic situatedness nor the factory’s ongoing demise has been a topic of discussion.

Inspired by Marcel Duchamp’s readymade With Hidden Noise (1917), a ball of twine placed between two brass plates, the two artists created an untitled hollow column out of concrete, situated in the first room of the exhibition on a board fixed to the wall. Visitors were encouraged to shake it, upon which one heard the sound of unknown small objects, presumably stones and rubble from a post-industrial landscape. The monotonous, mechanical and tinny rattle evokes a fleeting image of thousands of female workers in uniforms seated in front of their sewing machines performing textile work. Philosopher and cultural theorist Sadie Plant describes weaving practices as “communal, sociable work,” establishing close connections and “shuttle systems,” or networks in which data and information could circulate.(Sadie Plant, zeros + ones. Digital Women and the New Technoculture (London: fourth estate, 1998), 65.) After the end of the Ceausescu regime, these informal networks slowly started to petrify, to become static and invalid. Thus, the artist’s column turns into a symbolic rest of the once vital “shuttle system” between the women of APACA. It also carries many questions: How could solidarity among the APACA women under the supervision of the state and male authorities be established? And if this, indeed, happen, how did it fall apart?

In an untitled intervention aired on public television and included in the show, the two artists reported on a ghost of a woman named “Ana” haunting the site of the former APACA factory. Having worked at APACA for a long time, she, like many other women, became unemployed in the nineties. According to the artists’ conspirative storytelling, Ana became homeless and started to live in one of the former factory buildings, where she was protected by wild dogs until she was “accidentally” killed during the building’s demolition by Romanian businessmen Radulea. Speculating about Ana’s “fate,” Crunteanu and Hornung walk across the demolished wasteland towards the scene of the alleged crime. Installed in the staircase of Ivan Gallery, splitting the exhibition space’s two main floors, this video work is one of the core pieces in the exhibition, a fictional documentary responding to a pseudo-ancient, entirely fictitious myth.

In an untitled intervention aired on public television and included in the show, the two artists reported on a ghost of a woman named “Ana” haunting the site of the former APACA factory. Having worked at APACA for a long time, she, like many other women, became unemployed in the nineties. According to the artists’ conspirative storytelling, Ana became homeless and started to live in one of the former factory buildings, where she was protected by wild dogs until she was “accidentally” killed during the building’s demolition by Romanian businessmen Radulea. Speculating about Ana’s “fate,” Crunteanu and Hornung walk across the demolished wasteland towards the scene of the alleged crime. Installed in the staircase of Ivan Gallery, splitting the exhibition space’s two main floors, this video work is one of the core pieces in the exhibition, a fictional documentary responding to a pseudo-ancient, entirely fictitious myth.

This work is related to one of the four fundamental Romanian myths entitled Craftsman Manole (“Meterul Manole”), closely intertwined with the “female ideal” in Romania and other (post-) socialist societies and discussed by cultural theorists Florentina C. Andreescu and Sean P. Quinn.(Florentina C. Andreescu and Sean P. Quinn, “Women, language and sacrifice,” in Genre and the (Post-)Communist Woman. Analyzing transformations of the Central and Eastern European female ideal, ed. Florentina C. Andreescu et al. (London, New York: Routledge, 2015), 20.) During the construction of the Romanian Orthodox monastery Curtea de Arge, the architect and chief builder Manole faced a disastrous problem: the building always crumbled overnight. Manole dreamt that only a beloved woman could make the building remain stable by being buried alive inside a wall of the structure. He and his masons decided that the first woman to visit the construction site would be sacrificed. The first woman to arrive was Ana Manole, the chief builder’s pregnant wife. Tricked by Manole (who stuck to his plan) into playing a „game,“ she finally ended up being entombed alive. Thus, Craftsman Manole, regardless of its inherent fatalism, puts a spotlight on the role of women’s bodies. Ana Manole’s body becomes “the body of the nation,” “happily selected” and “blessed” to sacrifice her flesh to social and national authorities, represented by her husband, the lord and the church.(Andreescu and Quinn, 20-21.)

Following Andreescu and Quinn’s argument, one can assume that, during socialism, women were constantly obliged to perform sacrificial acts in the private and public domain. Under Ceausescu, women’s bodies belonged to the state—they had to endure pro-natalist policies from 1966 to 1989, which was already implemented in the Soviet Union thirty years earlier with the aim of increasing the number of potential workers. In Crunteanu and Hornung’s televised story, the restless “Ana” haunting the APACA wasteland is a product of the continuous appropriation of women’s bodies by the socialist state. Therefore, even during Stalinism, the woman’s body was instrumentalized as a productive body, combining biological reproduction with the socialist modernization project.(Susan Buck-Morss, Dreamworld and Catastrophe. The Passing of Mass Utopia in East and West (Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2002), 197.) Art theoretician Marius Babias notes the irony residing in the fact that it was the ideologically manufactured, ethnified and essentialized “generation of the ‘new people’” which finally ended the dictatorship in 1989.(The Romanian foreign politics of economical autarchy and corruption led to a great economical and social crisis from 1981 to 1989. Basic food provisions for the population as well as ressources such as coal, oil and electricity were lacking. Besides the economical poverty, Gorbachev’s perestroika entered Romania and made people think about the autocratic leadership and the human rights violations. Marius Babias, “The Euro-Self and the Europeanism. How the Communist National Discourse Acquires a New Face, That of the Post-Communist Anti-Modernism,” in Genealogies of Post-Communism, ed. Adrian T. Sîrbu, Alexandru Polgár (Cluj: Idea Design & Print, 2009), 261, 264f.) The women of APACA were part of this “new people,” having suffered for the sake of their nation and experiencing stigmatization. While the creation of the factory played a pivotal role in the creation of the “new man,” the “new woman” involuntarily stayed invisible. Subsumed under the “new man,” she, indeed, had the same occupation, but never gained an equal social status, or control over her own body. The conceptual outline that “Ana,” a homeless phantom who lives among APACA’s ruins, is examined by two contemporary artists attributes to her the status of a secular, heroic, and post-human figure.

An untitled photograph in the first room of Femina Subtetrix shows Hornung hanging a red pullover onto the frame of an overpainted, empty billboard in the city of Cotroceni, close to the former location of the APACA factory. This image references Roman’s trademark, a red pullover that marked his political orientation and displayed his nonconformity.(The red pullover also refers to the red uniforms of the factory’s leading workers that contrasted with the blue uniforms of the other workers.) Roman’s ignorance of the women’s situation within the walls of a crumbling factory—of their vulnerability in the face of its ending—appears to be repeated elsewhere in the photographic image. A textile object held in contrast with the stripped layers of an empty billboard offers a reflection on the growing commercial occupation of public space in post-socialist city centers. The red pullover appears to become an ironical symbol for the entanglement of politics, privatization and female labor, calling for a (re-)claiming of an increasingly diminished public space for artistic and political articulations.

An untitled photograph in the first room of Femina Subtetrix shows Hornung hanging a red pullover onto the frame of an overpainted, empty billboard in the city of Cotroceni, close to the former location of the APACA factory. This image references Roman’s trademark, a red pullover that marked his political orientation and displayed his nonconformity.(The red pullover also refers to the red uniforms of the factory’s leading workers that contrasted with the blue uniforms of the other workers.) Roman’s ignorance of the women’s situation within the walls of a crumbling factory—of their vulnerability in the face of its ending—appears to be repeated elsewhere in the photographic image. A textile object held in contrast with the stripped layers of an empty billboard offers a reflection on the growing commercial occupation of public space in post-socialist city centers. The red pullover appears to become an ironical symbol for the entanglement of politics, privatization and female labor, calling for a (re-)claiming of an increasingly diminished public space for artistic and political articulations.

The central photograph in the exhibition, also untitled, presents two young women with masked heads tenderly interacting in a deserted landscape. Their heads are wrapped in red shirts, and one is gently kissing the forehead of the other. Once again, the artists appropriate the historical event of Roman’s theatrical “paternal kissing.” Unlike Roman’s gesture, these women’s confidential kiss on the forehead creates a militant equality: two persons of the same gender, with their equally wrapped faces and common indications of youth consensually sharing an intimacy similar to the “socialist fraternal kiss.” This feminine, theatrical (re)staging of Roman’s “kissing performance” transfers the media image of the manipulated women workers into a resistant zone. The exhibition text for this work suggests that viewers perform this kiss with another visitor, implying a careful negotiation of what is being done, how and with whom.

The central photograph in the exhibition, also untitled, presents two young women with masked heads tenderly interacting in a deserted landscape. Their heads are wrapped in red shirts, and one is gently kissing the forehead of the other. Once again, the artists appropriate the historical event of Roman’s theatrical “paternal kissing.” Unlike Roman’s gesture, these women’s confidential kiss on the forehead creates a militant equality: two persons of the same gender, with their equally wrapped faces and common indications of youth consensually sharing an intimacy similar to the “socialist fraternal kiss.” This feminine, theatrical (re)staging of Roman’s “kissing performance” transfers the media image of the manipulated women workers into a resistant zone. The exhibition text for this work suggests that viewers perform this kiss with another visitor, implying a careful negotiation of what is being done, how and with whom.

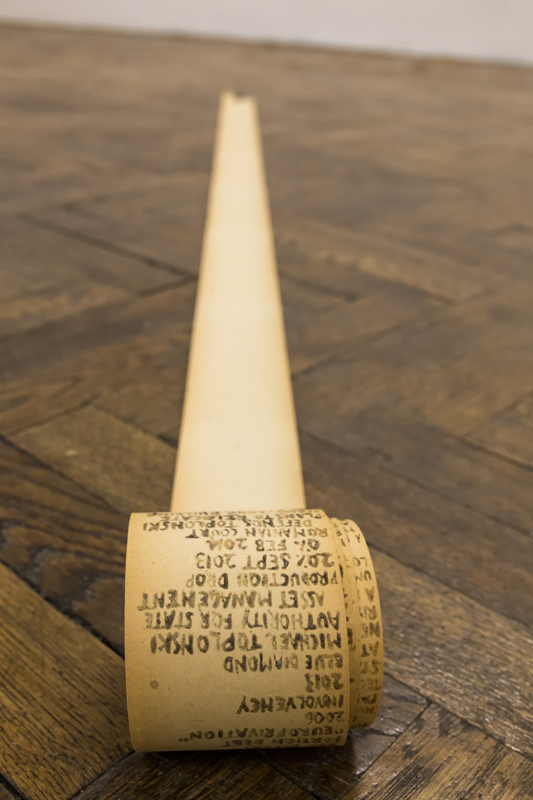

In front of these photographs and lying on the floor in the middle of the room, one discovered a light-brown, paper flag or banderole and one die. The banderole is an associative protocol of unfiltered observations from several walks and inquiries around the city of Bucharest by the artists. Numerous words are written in handmade ink on the banner, fragmentary notes and data all related to one point: the “drama of privatization,” as suggested by Boris Groys.(Boris Groys, Art Power (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2008), 165.)  Crunteanu and Hornung call the process of conversion from state ownership to private ownership not only a drama, but also a “melodrama of privatization,” which has left indelible marks on the urban fabric of Bucharest.(Email interview with the artists by author, November 16, 2015.) The banderole reads names of hotels, companies and investors, contingent street events, melodious real-estate projects, and fragments from the artists’ stream of consciousness. Listing all these unfiltered informations, this rolled-up paper strip can be understood as a real-time-script of this melodrama because every name and every word continues to theatrically overwrite socialism’s leftover topography.

Crunteanu and Hornung call the process of conversion from state ownership to private ownership not only a drama, but also a “melodrama of privatization,” which has left indelible marks on the urban fabric of Bucharest.(Email interview with the artists by author, November 16, 2015.) The banderole reads names of hotels, companies and investors, contingent street events, melodious real-estate projects, and fragments from the artists’ stream of consciousness. Listing all these unfiltered informations, this rolled-up paper strip can be understood as a real-time-script of this melodrama because every name and every word continues to theatrically overwrite socialism’s leftover topography.

Elsewhere in the exhibition, one encounters an untitled video work with the image of two red dots robotically circling APACA’s wasteland and filmed from a bird’s eye perspective. When viewed for a longer period of time, it becomes apparent that these are two female persons carrying circular, red shields on their heads, suggestive of Margaret Atwood’s dystopian novel The Handmaid’s Tale (1985), in which female characters are dressed in red uniforms, clothing that points to their societal position and function as “handmaids” for reproductive purposes. In this speculative fiction, the idea of the female body belonging to the nation becomes even more monstrous: throughout the lifetime of a “handmaid,” her body wanders to several commanders of the elite. The wandering of two red, abstract dots continues in a second video work, followed by anonymous, female hands indexing the dots’ movements, framed by a low-key drone camera aesthetic. Such distanced video images seem like pre-digital records of mysterious, phantomatic appearances hailing from a different time.

Another untitled video work shows a boardgame from above, while it refuses to disclose the game’s submatrix: its players, strategies and payoffs. The pawns of the game are all uniformly black and are navigated on the board without any transparent actions or choices; no wins or forfeitures are registered. This setup makes it impossible to track and analyze the players’ tactical maneuvers. Except for their female hands, the players remain invisible. The work thereby metaphorizes the transition period where, in the absence of a transparent and shared legal framework, factors like high unemployment rates, speculative transactions and growing corruption resulted in vast societal disorientation and demoralization.

Another untitled video work shows a boardgame from above, while it refuses to disclose the game’s submatrix: its players, strategies and payoffs. The pawns of the game are all uniformly black and are navigated on the board without any transparent actions or choices; no wins or forfeitures are registered. This setup makes it impossible to track and analyze the players’ tactical maneuvers. Except for their female hands, the players remain invisible. The work thereby metaphorizes the transition period where, in the absence of a transparent and shared legal framework, factors like high unemployment rates, speculative transactions and growing corruption resulted in vast societal disorientation and demoralization.

Together, Crunteanu and Hornung’s rather uncanny works point to the absence of a higher logic, to times of disorder and deficiency inRomania during the 1990s. The re-telling of the women’s experiences at APACA via the material is directed against the art of forgetting, which still dominates post-socialist reality. The missing titles and the cryptic, enclosed and processual aesthetics of their works engaged visitors in a quasi-archeological undertaking of indexical reading and analysis. Despite the artists’ closeness to the methodology of artistic research, the facts, documents and data are no integral part of the exhibition. Instead of a checklist of works, the visitor is given a set of instructions that ask for performative enactments and a dialogical partner to engage with. This strategy can be seen as a way to process human and digital second-hand memories: to take part in the task of indexical reading and to share thoughts, experiences and feelings with others. Like “the people of the future,” men and women, caught unprepared by the post-revolutionary melodrama of privatization, Crunteanu and Hornung, as both artists and representatives of a second generation of future people, articulate feelings of displacement, metaphysical loneliness and irony through their exhibition.

Together, Crunteanu and Hornung’s rather uncanny works point to the absence of a higher logic, to times of disorder and deficiency inRomania during the 1990s. The re-telling of the women’s experiences at APACA via the material is directed against the art of forgetting, which still dominates post-socialist reality. The missing titles and the cryptic, enclosed and processual aesthetics of their works engaged visitors in a quasi-archeological undertaking of indexical reading and analysis. Despite the artists’ closeness to the methodology of artistic research, the facts, documents and data are no integral part of the exhibition. Instead of a checklist of works, the visitor is given a set of instructions that ask for performative enactments and a dialogical partner to engage with. This strategy can be seen as a way to process human and digital second-hand memories: to take part in the task of indexical reading and to share thoughts, experiences and feelings with others. Like “the people of the future,” men and women, caught unprepared by the post-revolutionary melodrama of privatization, Crunteanu and Hornung, as both artists and representatives of a second generation of future people, articulate feelings of displacement, metaphysical loneliness and irony through their exhibition.