FEINKOST, Berlin (“Series Young Galleries in Eastern Europe”)

ARTMargins continues its series on young galleries in Central and Eastern Europe.

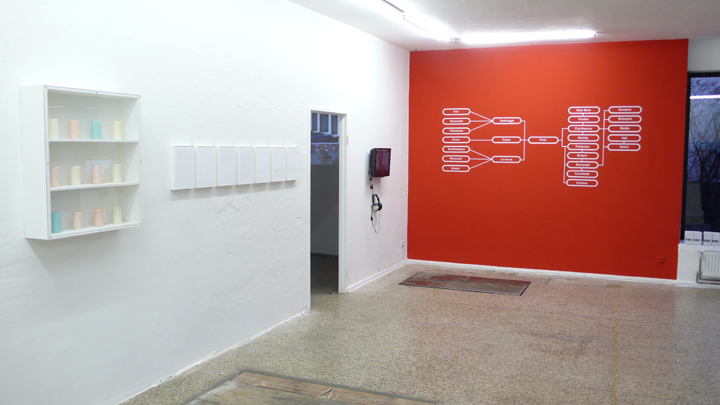

FEINKOST is located in a ‘50s-era glass pavilion on the former border between East and West Berlin. Built in the style of a poor-man’s Neue Nationalegalerie, the building was, until the early Noughties, a Feinkost, or “delicatessen.” In 2007 Mette Ravnkilde Nielsen and I started the gallery. Since that time its program has consisted of solo shows and group exhibitions that investigate the use-value of art in society and culture, taking into consideration the kind of lofty epistemological criteria that have ultimately been lost in the market-obsessed climate of the contemporary art world.

Today, it is fair to say that everyone expects more from galleries and institutions than the usual buttresses of celebrity, hype and merchandising that the art market and its operators have proliferated for the past decade or more. In that respect it is important to rethink the models of for-profit and non-profit and the preconceptions attached to each as they are often not so different from one to the other. Furthermore, it is of utmost importance that we each step back and ask ourselves about our own personal expectations of and preconceptions toward contemporary art and whether much of what we have been given by way of the pervasive institutionalization or canonization of practice actually deserves the status it has achieved. I think that the first way to do this is to properly analyze the market, force some level of transparency and, more generally, make people put their mouths where their money is.

Today, it is fair to say that everyone expects more from galleries and institutions than the usual buttresses of celebrity, hype and merchandising that the art market and its operators have proliferated for the past decade or more. In that respect it is important to rethink the models of for-profit and non-profit and the preconceptions attached to each as they are often not so different from one to the other. Furthermore, it is of utmost importance that we each step back and ask ourselves about our own personal expectations of and preconceptions toward contemporary art and whether much of what we have been given by way of the pervasive institutionalization or canonization of practice actually deserves the status it has achieved. I think that the first way to do this is to properly analyze the market, force some level of transparency and, more generally, make people put their mouths where their money is.

The Romantic and revolutionary side of art in Western civilization has been altogether gelded by its intense cash value. On top of that, the loss of locality resulting from globalization and the internationalization of art and culture makes the artistic output of Western civilization seem altogether homogenous, acultural and ahistorical. This cash-value situation structures far too heavily the criteria according to which people create and accept creativity. Once you take away the commercial or commodity status of art, its function changes drastically. Due to rampant insularity, art is no longer useful in helping people develop alternative perspectives on the world, changing perceptions of sentience or rerouting political, social and cultural pathways.

Historically, art has been seemingly subjugated to the visual tastes of a privileged class. Functionality or use-value are very recent facets of cultural production that, though not yet pre-requisites, comprise an ever-more pervasive part of audience expectations. The contemporary art object today has to have been made in consideration not only of the history of its material but also whatever other questions of precedence and furtherance arise in the processes of cultural validation and consecration. Eventually, we will begin to assess the value of the object or action against precedence, its agency within reality, philosophy or some other such field, and its ability to engage with a general and specific audience — and within all of this aesthetics will become a basic criteria rather than the fundamental goal.

Historically, art has been seemingly subjugated to the visual tastes of a privileged class. Functionality or use-value are very recent facets of cultural production that, though not yet pre-requisites, comprise an ever-more pervasive part of audience expectations. The contemporary art object today has to have been made in consideration not only of the history of its material but also whatever other questions of precedence and furtherance arise in the processes of cultural validation and consecration. Eventually, we will begin to assess the value of the object or action against precedence, its agency within reality, philosophy or some other such field, and its ability to engage with a general and specific audience — and within all of this aesthetics will become a basic criteria rather than the fundamental goal.

Many of the artists represented by FEINKOST were not trained to be artists and spent portions of their professional lives engaged in other fields. Arcangelo Sassolino’s background in industrial design and his usage of engineers and industries as artisans produces unique and threatening phenomena. Ignacio Uriarte studied Business Administration and worked for 10 years in cubicle life as a manager at companies such as Siemens. His practice filters office-based practices, materials and gestures through a conceptual and minimalist vernacular of the ‘60s and ‘70s. Others touch upon their own ethnic backgrounds in conceptual ways, as is the case in Daniel Baker’s instrumentalization of his Traveller upbringing and research towards a Roma Aesthetic, or Andisheh Avini’s mining of the layered consciousness of cultural identity through the Iranian diaspora. One way or another, they are all engaged with components of their respective realities in a bilingual way that collapses into their work and creates a scale of production and frame of reference that engages directly with reality in a confident way effacing aspects of the aforementioned.

One of the biggest difficulties for an artist is to avoid becoming locked within the context of one’s own practice. Curators are typically there to intellectualize and open the practices of individual artists to wider arguments and broader dialogue. Along these lines, the practices of artists represented by FEINKOST are continuously reinterpreted and tested in the context of group shows analyzing social, cultural and political structures. Placing young and emerging artists alongside established and/or underappreciated artists within well-considered thematic contexts allows those established artists to be seen in new ways while at the same time raising awareness of others who we at the gallery believe deserve it.

Due to Berlin’s seemingly endless resources of local and international art stars and up-and-comers, all operating within an arm’s reach of one another, it has been possible for us to work with artists who we would otherwise have had difficulty collaborating with due to their stature, such as Christian Jankowski, Douglas Gordon, Mike Kelley, Mike Bouchet, Dorothy Iannone and many others. We aim at highlighting artistic practices that are diverse in range and flexible in their applicability towards subjects. In its attempt to question the relevance of artistic practice to contemporary culture, the gallery practice tends towards blurring otherwise dated notions of the profit and non-profit binary within the contemporary art world.

Due to Berlin’s seemingly endless resources of local and international art stars and up-and-comers, all operating within an arm’s reach of one another, it has been possible for us to work with artists who we would otherwise have had difficulty collaborating with due to their stature, such as Christian Jankowski, Douglas Gordon, Mike Kelley, Mike Bouchet, Dorothy Iannone and many others. We aim at highlighting artistic practices that are diverse in range and flexible in their applicability towards subjects. In its attempt to question the relevance of artistic practice to contemporary culture, the gallery practice tends towards blurring otherwise dated notions of the profit and non-profit binary within the contemporary art world.

From a curatorial standpoint FEINKOST has put together exhibitions that through journalistic, anthropological and/or essayistic methods have investigated topics simultaneously emerging in news media and popular thinking. This is evidence that commercial galleries represent potentially the most advanced guard available in cultural production for disseminating ideas and putting concepts into action. Examples therein include the exhibitions detailed below.

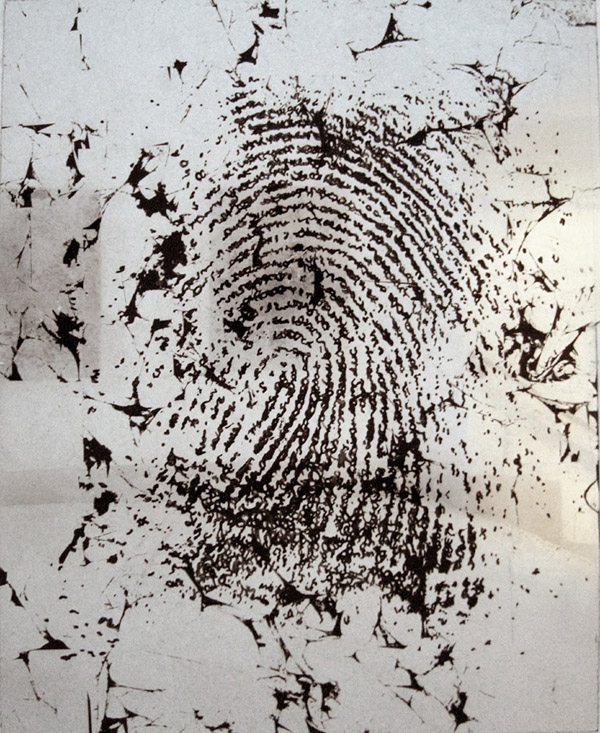

The Art World was an anthropological study of the art world and its mechanisms, including academicization, rhetoric, social networking and economy. This occurred shortly after the gallery opened and shortly before the market crashed, at a point when there was little or no criticism of the problematics and opacity of the art world. It was an exhibition borne out of the dilemma faced by an institutional critique that has been widely “institutionalized,” leading to an overall complacent and often complicit attitude. Projects were selected for their case-study-like ability to open windows onto areas of this hermetic industry rather than merely aestheticize it. Subjects like deaccessioning, disauthetication, etiquette, profiling, production of false icons, manipulations of markets, exploitation, authorship of history, and the larger questions of the actual value of global art in relation to local culture were put on the table. Even though a proper exegesis is still in order, if one were to produce such an exhibition today it would not only be obvious but seem overly cynical towards something that we are now all openly fed up with.

The Art World was an anthropological study of the art world and its mechanisms, including academicization, rhetoric, social networking and economy. This occurred shortly after the gallery opened and shortly before the market crashed, at a point when there was little or no criticism of the problematics and opacity of the art world. It was an exhibition borne out of the dilemma faced by an institutional critique that has been widely “institutionalized,” leading to an overall complacent and often complicit attitude. Projects were selected for their case-study-like ability to open windows onto areas of this hermetic industry rather than merely aestheticize it. Subjects like deaccessioning, disauthetication, etiquette, profiling, production of false icons, manipulations of markets, exploitation, authorship of history, and the larger questions of the actual value of global art in relation to local culture were put on the table. Even though a proper exegesis is still in order, if one were to produce such an exhibition today it would not only be obvious but seem overly cynical towards something that we are now all openly fed up with.

More Love Hours Than Can Ever Be Repaid functioned as an antidote to the market’s collapse and a way to re-establish criteria by which to determine notions of value. Love Hours quantify the time/effort/love one invests in making something that does not proportionally reflect all that went into making it. We paired mothers and their children–Daniel and Celia Baker as well as Sarah Pucci and Dorothy Iannone—in order to begin with the most primal point of the subject. From there, O.C.D. abstraction and a therapy of labor moved towards the desire to balance the world on a pinhead, until alternative economies and new forms of value began to emerge. Each project in Love Hours tried to imagine art possessing a value that goes beyond price, one that is electrified by the energy of its maker — energy made almost tangibly present for the viewer as seen through each work’s process, purpose and materials.

More Love Hours Than Can Ever Be Repaid functioned as an antidote to the market’s collapse and a way to re-establish criteria by which to determine notions of value. Love Hours quantify the time/effort/love one invests in making something that does not proportionally reflect all that went into making it. We paired mothers and their children–Daniel and Celia Baker as well as Sarah Pucci and Dorothy Iannone—in order to begin with the most primal point of the subject. From there, O.C.D. abstraction and a therapy of labor moved towards the desire to balance the world on a pinhead, until alternative economies and new forms of value began to emerge. Each project in Love Hours tried to imagine art possessing a value that goes beyond price, one that is electrified by the energy of its maker — energy made almost tangibly present for the viewer as seen through each work’s process, purpose and materials.

Schengen was an exhibition revealing the ways in which artists, cultural critics and architects were understanding and using the Europeanization process as a material in their practice. Among others, OMA/AMO’s flag for the EU, Matei Bejenaru’s illegal immigration instructions, Pablo Helguera’s Conservatory of Dead Languages and Hito Steyerl’s Universal Embassy generated a composite sketch of Schengen that promotes Europe through re-envisioning borders, disappearing locality, and the creation of national palimpsests and informal markets. The Kiev-based REP Group produced the work Contraband, which showed members of the group inflating colorful balloons with methane gas and hot water bottles with oil, materials that were then strapped and tied to their bodies. The aim of the “performance” was to see whether they could successfully import insignificant quantities of fuel from the Ukraine into Poland. The commentary, in this case, could not have been more direct. Made at a time when Gazprom had recently shut off the pipes to the Ukraine, in this video we witnessed an imaginative emergence of alternative economies resulting from the geostrategic manipulation of Ukraine’s position by Russia. Even if to an almost absurd degree, the gesture ultimately reflects the conditions that might lead even the common person to go to such lengths in order to import the lucrative materials that lubricate foreign policy in the world.

Schengen was an exhibition revealing the ways in which artists, cultural critics and architects were understanding and using the Europeanization process as a material in their practice. Among others, OMA/AMO’s flag for the EU, Matei Bejenaru’s illegal immigration instructions, Pablo Helguera’s Conservatory of Dead Languages and Hito Steyerl’s Universal Embassy generated a composite sketch of Schengen that promotes Europe through re-envisioning borders, disappearing locality, and the creation of national palimpsests and informal markets. The Kiev-based REP Group produced the work Contraband, which showed members of the group inflating colorful balloons with methane gas and hot water bottles with oil, materials that were then strapped and tied to their bodies. The aim of the “performance” was to see whether they could successfully import insignificant quantities of fuel from the Ukraine into Poland. The commentary, in this case, could not have been more direct. Made at a time when Gazprom had recently shut off the pipes to the Ukraine, in this video we witnessed an imaginative emergence of alternative economies resulting from the geostrategic manipulation of Ukraine’s position by Russia. Even if to an almost absurd degree, the gesture ultimately reflects the conditions that might lead even the common person to go to such lengths in order to import the lucrative materials that lubricate foreign policy in the world.

The Schengen exhibition coincided with the 2008 dissolution of the borders that divided Eastern and Western Europe. It was accompanied by a solo exhibition of gallery artist Daniel Baker, the previously mentioned English Traveller who featured prominently in the OSI-funded first Roma pavilion at the Venice Biennale the year prior. The pairing was meant to question the side effects and potential homogenization of Europe by placing the standardization accords alongside an artist whose heritage links him to those who could be considered the original European citizens.

The Practice of Everyday Life, based on the eponymous book by Michel de Certeau examined the ways in which artists make projects that replicate production and consumption processes precisely in order to simulate the original purpose, product or service they are imitating, like a kind of ouroboros. For example, dressing up like a street cleaner and cleaning the street, or becoming and being accepted as a pop star. The first audience is the passerby who believes what he sees to be what it seems and the second audience is the gallery-goer who understands the performative nature of it. The idea was not only based in performance but also in design and the construction of everyday behaviors. It asked, moreover, how the artist might have more potential to affect a change in everyday reality than his professional counterpart, working legitimately within the respective profession that is being performed. The show looked at different ideas of bricolage starting with moments where one has a need or a desired outcome and must make use of his own means in order to achieve it. This lead into what I would refer to as “occupational bricolage,” in which artists use occupations as media. The conclusion focused on projects that interrupt, change or maintain a status quo or expectations; i.e. things that are cleanly sublimated into a reflex of functional use by the passerby or everyday consumer.

The Practice of Everyday Life, based on the eponymous book by Michel de Certeau examined the ways in which artists make projects that replicate production and consumption processes precisely in order to simulate the original purpose, product or service they are imitating, like a kind of ouroboros. For example, dressing up like a street cleaner and cleaning the street, or becoming and being accepted as a pop star. The first audience is the passerby who believes what he sees to be what it seems and the second audience is the gallery-goer who understands the performative nature of it. The idea was not only based in performance but also in design and the construction of everyday behaviors. It asked, moreover, how the artist might have more potential to affect a change in everyday reality than his professional counterpart, working legitimately within the respective profession that is being performed. The show looked at different ideas of bricolage starting with moments where one has a need or a desired outcome and must make use of his own means in order to achieve it. This lead into what I would refer to as “occupational bricolage,” in which artists use occupations as media. The conclusion focused on projects that interrupt, change or maintain a status quo or expectations; i.e. things that are cleanly sublimated into a reflex of functional use by the passerby or everyday consumer.

The goal of the show was also to question the continuing professionalization of artists in realms reaching far outside typical studio practice: art and ecology/urbanism/design/etc., which are often merely flirtations with reality through the aestheticization of discourse. Operating within the art world allows a healthy safety net that liberates the practitioner’s credibility from the potential errors of any legitimate trials.

Andisheh Avini’s exhibition Homesick was timed with the 30th anniversary of the Iranian Revolution and, coincidentally, the uprising against the re-election of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. The current summer exhibition, David Levine: Hopeful, is about looking at cultural waste, the pursuit of celebrity, and relentlessness of self-promotion; analogies rooted in the nature of the art world but in this case directed at the mechanisms of Hollywood’s hopefuls. And while the parallel is rather cringeworthy, it is nonetheless appropriate that Michael Jackson should have met his demise within days of the inauguration.

Andisheh Avini’s exhibition Homesick was timed with the 30th anniversary of the Iranian Revolution and, coincidentally, the uprising against the re-election of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. The current summer exhibition, David Levine: Hopeful, is about looking at cultural waste, the pursuit of celebrity, and relentlessness of self-promotion; analogies rooted in the nature of the art world but in this case directed at the mechanisms of Hollywood’s hopefuls. And while the parallel is rather cringeworthy, it is nonetheless appropriate that Michael Jackson should have met his demise within days of the inauguration.

This July FEINKOST was invited by the gallery Brown in London to make an exhibition about the gallery and its artists. This was the first time a curatorial statement was structured exclusively around artists associated with or represented by the gallery. None of the artists we worked with on this exhibition have anything in common within their respective practices apart from their association with the gallery, and therefore it was an excellent challenge to make a cohesive statement in regards to their work. In effect, the exhibition Sleeper put nine international artists together under a rather sinister light. The theme looked at the notion of suddenly becoming something else, as if awakening under a directive. In this case, the exhibition concept scrutinized the nature of curatorial practice, reinterpreting artistic practices and projects that carry their own specific meanings by suddenly placing them in altogether different roles.

This July FEINKOST was invited by the gallery Brown in London to make an exhibition about the gallery and its artists. This was the first time a curatorial statement was structured exclusively around artists associated with or represented by the gallery. None of the artists we worked with on this exhibition have anything in common within their respective practices apart from their association with the gallery, and therefore it was an excellent challenge to make a cohesive statement in regards to their work. In effect, the exhibition Sleeper put nine international artists together under a rather sinister light. The theme looked at the notion of suddenly becoming something else, as if awakening under a directive. In this case, the exhibition concept scrutinized the nature of curatorial practice, reinterpreting artistic practices and projects that carry their own specific meanings by suddenly placing them in altogether different roles.

Today, thanks to Bush-era aftershocks, the definition of the sleeper has been overloaded with Hollywood tales like The Manchurian Candidate and The Bourne Identity, as well as the media’s pervasive trawling for homegrown threats, terrorist cells, and secret agents. This exhibition plotted out a scene of criminal intent, connecting disparate artistic practices to create a theater of interpretation.

The result ultimately allowed each practice to retain the trace of its origin while being forced within the structure we had created for it. The effort also coincided with the fourth anniversary of the July 7th terrorist attacks in London. This timing was not a way to be insensitive or controversial but rather to test the relevance of a topic that has become taboo and yet also somehow passé in the wake of the Bush presidency.

Today we are fortunately nearing the other side of an important plateau never before crossed in the history of the art world or cultural production. As we sit back holding our breath waiting to understand exactly how we will emerge from a global economy in shambles, redirecting our interests away from capital investment art that is now receiving much deserved speculation, the hope is that a new quest for genuine content will begin. Heavy-handedness, opinion and conviction are how the art world has made it this far. The gallery practice and the artists whose work gets represented through it could seem mere drops in the bucket of Berlin’s 500+ galleries. However our efforts towards re-envisioning purpose into cultural production and applying that purpose in contributive ways not only makes everyone reflect on the nature of their own practice as artist, gallerist or curator but hopefully brings a much-needed and noticeable relevance to art in everyday life.

Other essays in this series: