Artists from Eastern Europe in Berlin: Ewa Partum

This conversation is part of a series of interviews with artists from Eastern Europe who live and work in Berlin. The city has attracted artists from Eastern Europe for a long time: especially during the Cold War and into the 1990s, its peculiar geo-political situation gave it a unique ambience that attracted artists from all over the world, but especially from the East. How do these artists experience the city today? How do they look back on the hopes and expectations with which they once arrived? Have they settled for good, or are they considering moving elsewhere? Do their Eastern European origins still matter for their art making?

Sven Spieker: During the time of the Cold War, Poland was generally less isolated than other countries in the former Eastern Bloc. Additionally, mail art had created many connections between Polish artists and artists in other parts of the world. Did you have contacts in Berlin before you came here?

Ewa Partum: Yes, I had contact with people in Berlin, for instance Wolf Vostell, the Fluxus artist, and also a group of Berlin feminists. Because of the activities at my gallery (Adres), I had contacts and knew some names.(Ewa Partum founded Adres Gallery in ?ód? in the spring of 1972. Initially the gallery was located in a small space at the Association of Polish Artists (ZPAP). In 1973, the gallery was expelled from its location and re-located by Partum to her apartment. Gallery Adres was a part of a transnational mail art network, and a point of contact with Fluxus artists such as Dick Higgins, Ben Vautier, Eric Anderson, and Robert Fillou who since the mid-1960s had worked together with artists from Eastern Europe. Between 1972-1977, Partum organized a series of individual and group exhibitions and presentations by, among others, Krzysztof Wodiczko, Józef Robakowski, Zbigniew Warpechowski, Endre Tót, Maurice Roquet, Robert Filliou, Ben Vautier, Pierre Garnier, Jochen Gerz, Richard Kostelanetz, Robin Crozier, Eric Anderson, Christian Wapler, Samogyi György, Ji?zí Kocman, Ji?zí Valoch, Gerta Pospíšilová, Josef Jankovi?, and Martin He?manský.) Again, Vostell was a prominent Fluxus participant, and I knew he was in Berlin. We met in person in 1977 in Warsaw, where he had an exhibition at Studio Gallery. I also showed documentation of Vostell’s work at Adres Gallery.

Ewa Partum: Yes, I had contact with people in Berlin, for instance Wolf Vostell, the Fluxus artist, and also a group of Berlin feminists. Because of the activities at my gallery (Adres), I had contacts and knew some names.(Ewa Partum founded Adres Gallery in ?ód? in the spring of 1972. Initially the gallery was located in a small space at the Association of Polish Artists (ZPAP). In 1973, the gallery was expelled from its location and re-located by Partum to her apartment. Gallery Adres was a part of a transnational mail art network, and a point of contact with Fluxus artists such as Dick Higgins, Ben Vautier, Eric Anderson, and Robert Fillou who since the mid-1960s had worked together with artists from Eastern Europe. Between 1972-1977, Partum organized a series of individual and group exhibitions and presentations by, among others, Krzysztof Wodiczko, Józef Robakowski, Zbigniew Warpechowski, Endre Tót, Maurice Roquet, Robert Filliou, Ben Vautier, Pierre Garnier, Jochen Gerz, Richard Kostelanetz, Robin Crozier, Eric Anderson, Christian Wapler, Samogyi György, Ji?zí Kocman, Ji?zí Valoch, Gerta Pospíšilová, Josef Jankovi?, and Martin He?manský.) Again, Vostell was a prominent Fluxus participant, and I knew he was in Berlin. We met in person in 1977 in Warsaw, where he had an exhibition at Studio Gallery. I also showed documentation of Vostell’s work at Adres Gallery.

SS: You finally settled in Berlin after the imposition of martial law in Poland in 1981, invited by Vostell. How did you experience the city and the art scene at the time? Was it difficult to be recognized as an artist from Eastern Europe, and as a woman?

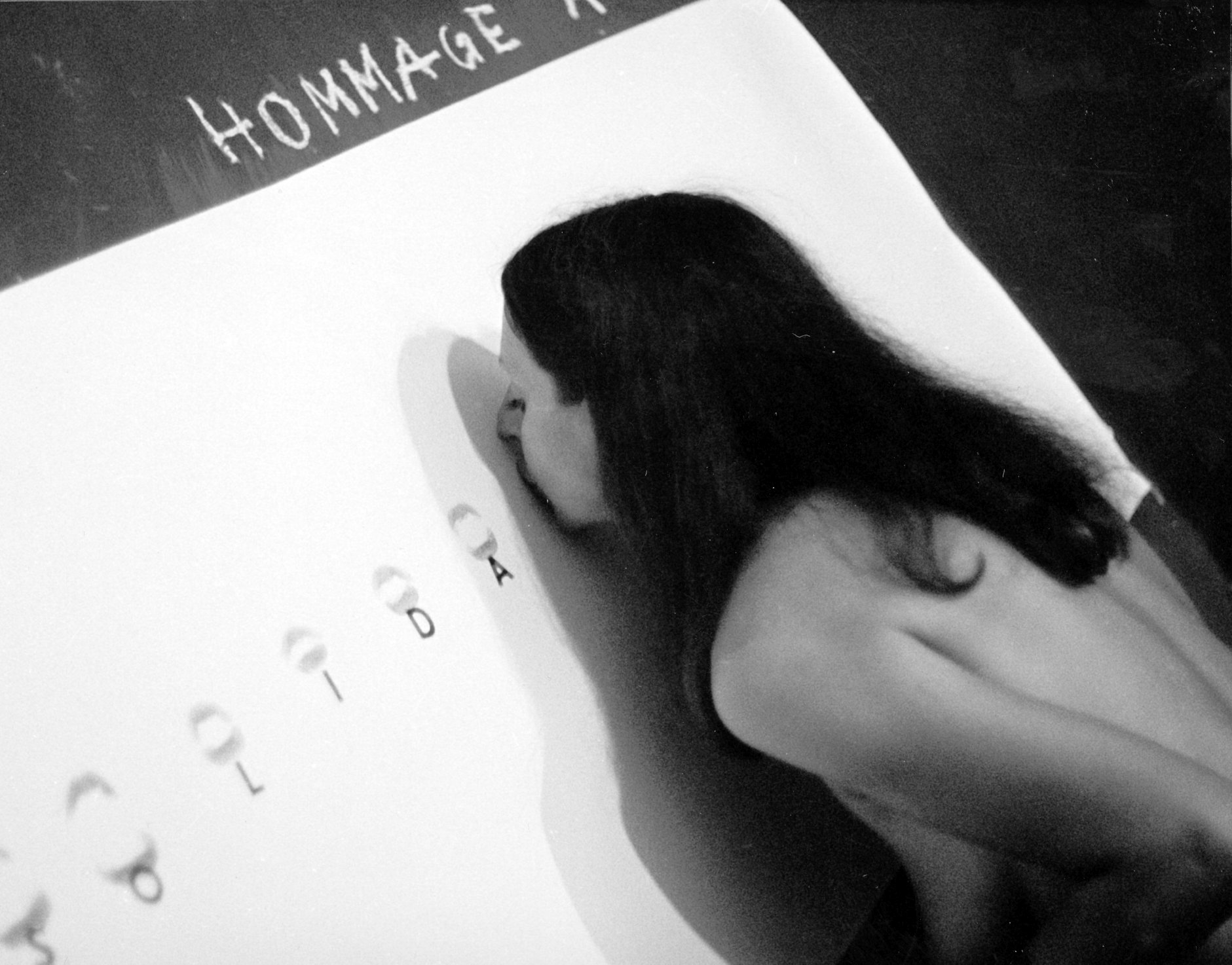

EP: First of all, I was very happy that I was able to leave Poland; it was not easy. There were many obstacles, and it took time to receive my passport. First I met with Vostell and his circle, the friends who helped me settle. But I was very shocked and surprised because in Berlin there was no conceptual art at all. Everyone was making paintings and selling them! Once I was invited to a dinner at Vostell’s house. His wife was cooking, and he was showing me a catalogue. I couldn’t believe that it was his work; it was pure painting. I had this innocent idea that in the West artists were living art through happenings and performances, and it was shocking to see that they were painting. I thought that they were not using this conventional art form anymore. Once I had learned to speak a little bit of German and had started to organize my practice again, I called some gallerists. One of them was organizing an exhibition on constructivism and even asked me, “What is conceptual art?” This happened in 1983. There was a little bit of interest in my art in Berlin due to the fact that everyone was talking about Solidarno?? at the time. Before coming to Berlin I had a performance called Hommage à Solidarno??, and this work generated interest. From this particular point of view they were interested in Poland. There was this exhibition going on at the Checkpoint Charlie Museum (run by Rainer Hildebrandt, the human rights activist). They were interested, and I was invited to take part. This first show I participated in there was in 1982, in the context of Solidarno??, but they took the work and used it historically.

SS: Did you meet your first gallerist, Michael Wewerka, through Vostell?

EP: It was the other way around. Once I was at an exhibition at Wewerka’s gallery when Vostell was also present, and I introduced them. I encouraged Wewerka to show Vostell. At the end of March 1983, I went to Wewerka’s gallery with my translator (the person who helped me with English. He was the same person with whom I collaborated at Adres Gallery). Wewerka was very interested in women, and he realized that I had a lot of work with naked bodies. He said, “Don’t forget, in a week you will have an exhibition at my place!” He even produced a catalogue. I asked Vostell to write a little essay for my catalogue, but he said that he was too busy with his own projects.

SS: Did Wewerka and Vostell get along?

EP: Once when Vostell looked at a catalogue of a show I was in, he asked how many works Wewerka bought from me for himself. I said none. Vostell was critical of Wewerka. I told him he should educate Wewerka to be a better gallerist.

SS: Was Wewerks able to sell your work?

EP: He bought two works for himself. Vostell told him to, and later he started buying a lot of works from Vostell; he even bought a house next to his.

SS: Could you say a few words about the gallery scene in Berlin at the time and how you experienced it, outside of your relationship with Wewerka’s gallery?

EP: With Wewerka it was mostly Neue Wilde, or neo-expressionsim, but also artists who did something, even if we didn’t know exactly what it was. Wewerka was mostly friends with pretty girls. But there was also Schiller Gallery, of which I knew from Wewerka, where they showed Fluxus. But Wewerka said they had no money. Because of that specific time in Berlin, the perception was that everybody did what they liked. There was no academic knowledge; it was just fun. The only institution that introduced any kind of structure to the scene was the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD). The galleries were commercial, and the gallerists were basically salespeople. Just like today.

SS: Conceptual art is often created with an international outlook. Did this attract you to this form of art making? Did you share the internationalism of contemporary conceptual art at that time?

EP: Yes, it was important for me to cross boundaries with this kind of work. It was not about making material or large works of art but to communicate with other artists through art

SS: Were you interested in Fluxus? You shared Vostell’s interest in television and other mass media.

EP: To a large extent. There was this expression in Polish that TV is “chewing gum for the eyes.” So totally negative.

SS: Is this what inspired you to work with television yourself?

EP: I appropriated it to make a conceptual work of art. At the same time, it was also a kind of structuralist investigation because I was using an 8 mm camera, and TV filming used different timing. The time lapses I created were an investigation of the structural problems of film. The work that I’m talking about is called Drawing TV and it was exhibited at the exhibition The First Generation. Art and the Moving Image 1963- 1986 at Reina Sofia in Madrid. They were interested in this work because of the different time of the camera and film. This exhibition put this work in the context of structuralist experiments with film.

SS: When you first arrived in Berlin, as you mentioned, it was the time of the Neue Wilde hegemony over the local art scene. Did you have any contact with these artists, or with any of their representatives?

EP: This was a separate circle, and I didn’t know any of them. That is why I had so much difficulty finding galleries. I didn’t have any contacts. And there were no conceptual galleries in Berlin at the time.

SS: Your language-based work, in which you use letters and words, is often to do with problems of communication. Did you feel that this theme had a particular resonance during the Cold War in Berlin?

EP: The work related to Solidarno?? did have resonance.

SS: In one of your most iconic performances from 1984 (East/West Shadow) you stood naked in front of the Berlin Wall. You have said that, in displaying your body naked, your interest was in the body functioning formally as a sign. Was this the case with the Wall performance as well? How intensely did you live the East/West divide that manifested itself at the Berlin Wall?

SS: In one of your most iconic performances from 1984 (East/West Shadow) you stood naked in front of the Berlin Wall. You have said that, in displaying your body naked, your interest was in the body functioning formally as a sign. Was this the case with the Wall performance as well? How intensely did you live the East/West divide that manifested itself at the Berlin Wall?

EP: The 1984 piece was documented for the public, but it was more of an action. It wasn’t made for the camera. I just wanted to perform it. I wouldn’t call this a camera action.

SS: When you say you didn’t want it to be a camera action, this means you didn’t want it to be for the camera? It wasn’t meant to be photographed?

EP: No, it was photographed, but I would say that it was a performance, not a camera performance. The photographs are just documentation. I would rather call it an installation. I was trying to stand in front of this wall. I was, indeed, using my body as a sign. I am still experiencing this [East/West] divide, in a way, when I’m selling my works to collections because I am told that artists from the Eastern Bloc don’t fetch the prices that I want, especially women.

SS: You are often identified, and you’ve identified yourself, as a feminist artist. Is this, for you, a universal position, or is there something particularly Polish to your engagement as a feminist? And also, if the answer is yes, how was your feminism affected by your move to Berlin?

EP: It was complicated. In Poland I was using the body as a feminist weapon. During the opening of my show Self-Identifcation in 1980 I declared that I would perform naked until the situation of women in the art market, in the social context, and everywhere else was equal to men’s. Then, in the West, suddenly, I came across all these places where naked women were selling themselves. On every corner there were images of naked female bodies, products of consumption. It just destroyed the context. I could walk through the crowds in Warsaw naked; but here I couldn’t because I would immediately meet somebody who was also naked but for different reasons. Everything in Berlin was so money-oriented. For instance, the feminist gallery Andere Zeichen proposed to organize an exhibition for me, but I would have to pay for the organization and for things like the electricity. Everybody had to pay. I had never encountered this type of situation where artists, feminists, had to pay for everything. This was intolerable, and also not possible for me for economic reasons. In Berlin feminists thought that it was enough to think of yourself as a feminist, but that then you could go on to make traditional art. You didn’t have to be avant-garde. You just had to be a feminist. What, for me, was important, on the other hand, was for feminist art to be avant-garde. This started with conceptual art, for by then I had already created my own conceptual language. Once I had formulated it, I wanted to do something that was important not only for art circles and art professionals, but for other people too, for society. This is what feminism meant to me, the need to do something for others. Because I was a woman, I wanted to make art for other women. But here in Berlin the feminists believed that you could employ any traditional formula to make “feminist” art.

SS: Did you believe that the art form that was most adequate for feminism was conceptual art?

EP: In a way the answer is yes. I came from this conceptual background, and then I made my feminist art based on thelanguage of conceptualism. I was using art forms that are relevant for feminist art: installation, performance, photography. Most of these works were accompanied by texts.

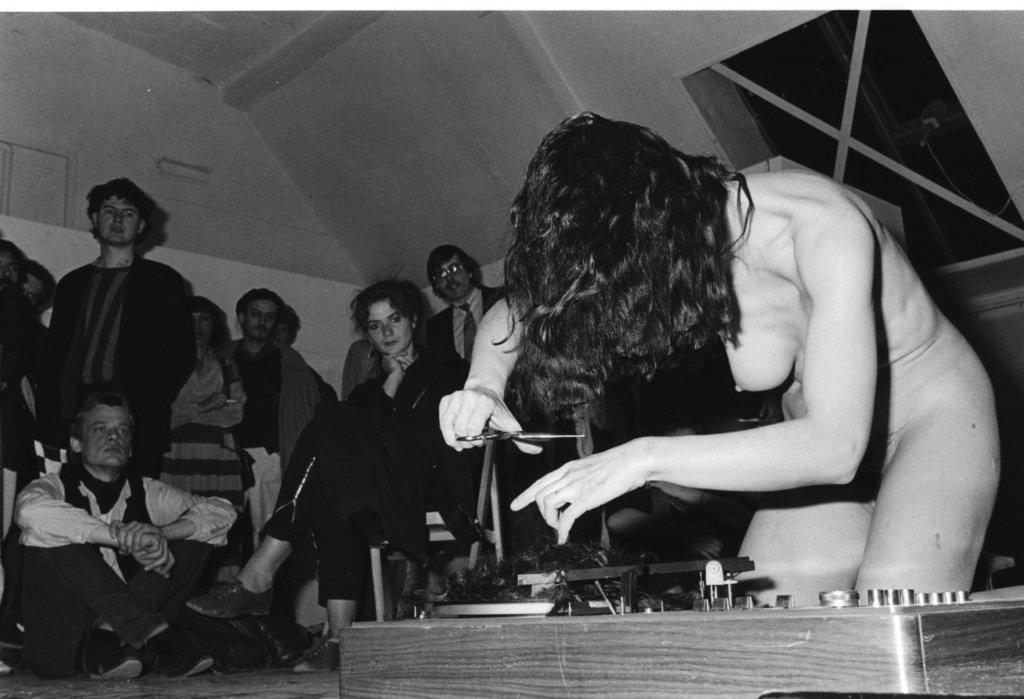

SS: In 1983 you performed Concert of Hair [Koncert w?osów] at Gallery Wewerka here in Berlin. Can you recall this event?

EP: I created three performances, and the first of these I performed was Koncert w?osów. There was also Hommage à Solidarno??, and then Stupid Woman. It was a series, and there was a documentation of these performances. Regarding Concert of Hair, I owned this vinyl record of Arthur Rubenstein and I explained to Wewerka that I needed a record player and that I would be cutting my own hair on top of the turning record. Wewerka said, “My god, are you going to destroy your beautiful hair?” So, I entered the room, music was playing, Chopin’s Concert in f-moll. I was naked and started saying, “How beautiful is the music of Frederic Chopin! How beautiful is the music of Arthur Rubenstein!” During all this time, I kept appreciating the music aloud, commenting and displaying my appreciation. Eventually the record got stuck with all the hair that had accumulated on top of it. My performance relates to Polish Romanticism, Romantic music, and to Rubenstein as its best performer. The performance was about the construction of a certain aesthetic: I created a work of art through the destruction of that aesthetic. Afterwards my hair was in bad shape. So there was a running joke after the performance that when somebody had badly cut hair this was to be called a “koncert w?osów,” as in “My son has a koncert w?osów today”.

SS: Could you also say something about another performance you did in Berlin, for example Stupid Woman (1983)?

EP: Hommage à Solidarno?? was very positively received. The point of the reviews was that because I was naked, I was trustful and vulnerable, believing no one would hurt me. In Stupid Woman, I quoted from Sartre’s text The Imaginary. There was this line about a woman who was following a dream (marzenie) she had had. She becomes obsessed with this dream to the extent that she completely became detached from reality. This was a model of schizophrenic behavior that related to the way in which women are being formatted in a society that demands from them to look beautiful; to be both sexy and a wonderful mother; to be full of compassion and care for others, etc. So in 1981 I wrote a short text inspired by some passages from Sartre’s The Imaginary that I used in this performance:

Stupid Woman

…so one can choose feelings that one wants to accept

like an actor choosing a costume.

Today this will be an ambition,

tomorrow, an obligation in love.

One would be making a mistake, therefore, to accept the

schizophrenic world

as a stream of wealth and luster

that replace the monotony of reality.

If I can

imagine so many love scenes,

it is not because I was disappointed in my love,

but just because one is no longer capable of loving.

…to be beautiful

…to smell beautiful

…to be nice to one’s own public

…really to be.

I was also drinking during the performance (the sparkling wine was cheap and so I had a headache afterwards), and I asked the men in the audience if they loved me and if they wanted to drink with me. They could also kiss me if they wanted to. So I asked one German visitor, and he looked at me and reflected for a while on the question. Yet this was the cultural difference between a Polish and a German audience! In Poland, everyone would have said that they loved me, and then they he would have kissed my hand. It was a very provocative, confrontational performance. I spontaneously kissed the men in the audience. They couldn’t decide if I was drunk or if it was part of the artistic concept. I sang Duchamp’s composition for his sisters. I finished, and when the lights came on at the end I said “thank you very much for the performance,” just to eliminate any doubt that this really had been a performanc

I was also drinking during the performance (the sparkling wine was cheap and so I had a headache afterwards), and I asked the men in the audience if they loved me and if they wanted to drink with me. They could also kiss me if they wanted to. So I asked one German visitor, and he looked at me and reflected for a while on the question. Yet this was the cultural difference between a Polish and a German audience! In Poland, everyone would have said that they loved me, and then they he would have kissed my hand. It was a very provocative, confrontational performance. I spontaneously kissed the men in the audience. They couldn’t decide if I was drunk or if it was part of the artistic concept. I sang Duchamp’s composition for his sisters. I finished, and when the lights came on at the end I said “thank you very much for the performance,” just to eliminate any doubt that this really had been a performanc

SS: After the fall of the Wall, Berlin’s art scene changed dramatically, and interest in artists from Eastern Europe intensified. How did these changes affect your existence as an artist here in Berlin?

EP: It became really difficult to get grants and support. Everything went to the East Germans. Suddenly there were plenty of artists from the East nobody had heard about before, and they didn’t do anything important in my eyes. Vostell said that they lacked quality. It was a little like the combination of wine and water. In 1993 I was invited to show at an exhibition organized by Christiane Müller, a gallery that showed only women artists from East and West Berlin. There were some very conservative artworks in the show that I didn’t want to be associated with. The artists from East Berlin were making excuses by saying that they did not know art because they had been isolated in the East. I was even more from the East! Yet it was very easy for them to get money to support their projects in East Berlin, while it was difficult to support anything in the Western part of the city.

SS: Recently, there has been a dramatic upsurge in interest in your work, with several retrospectives. Do you feel that your background in the former Eastern Europe is important for this renewed interest, or has the “global” approach to art erased the relevance of your background in the “former East”?

EP: I perceive this more as an upsurge in interest in art from the 1970s. It’s an interest driven by the art market. The classics from the ’70s, have their price. Suddenly the market discovered “Eastern” conceptualists and their continued relevance. New generations of curators discovered them, too. In the 1980s, there was no interest in conceptual art produced in the East. My feeling is that artists themselves ought to know the value of their work.

SS: Thank you very much.

Berlin, October 10, 2016 (Transcription: Gabe Wilson

Other interviews in this series:

Nika Radić